Book review: Beauty is in the Street: Protest and Counterculture in Post-War Europe by Joachim C. Häberlen (Allen Lane, 2023)

By chance, the legendary Italian intellectual Umberto Eco found himself in Eastern Europe just as 1968’s wave of revolts was erupting on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Noting the striking contrasts with the student-led rebellions taking place in his home country, Eco penned a report for an Italian magazine on what he had witnessed on the streets of Prague and Warsaw. Any East-West interchange, he suggested, was bound to be a dialogue de sourds (“dialogue of the deaf”). As a Polish friend explained it to him: “For you it’s just a theory. But we have practical problems to solve.”

Though one could indeed sense a pan-continental resonance in the events of that year, that which Eco observed in Eastern Europe had little in common with the carnival of reverie and hedonism that was rolling through Rome, Paris, West Berlin and Amsterdam. Whereas Czechoslovak youths were willing to stare down Soviet tanks in the name of a reformed, humane socialism, West German countercultural activists could impudently quip, “Dude, we want to make a revolution! Why should we care about politics?”

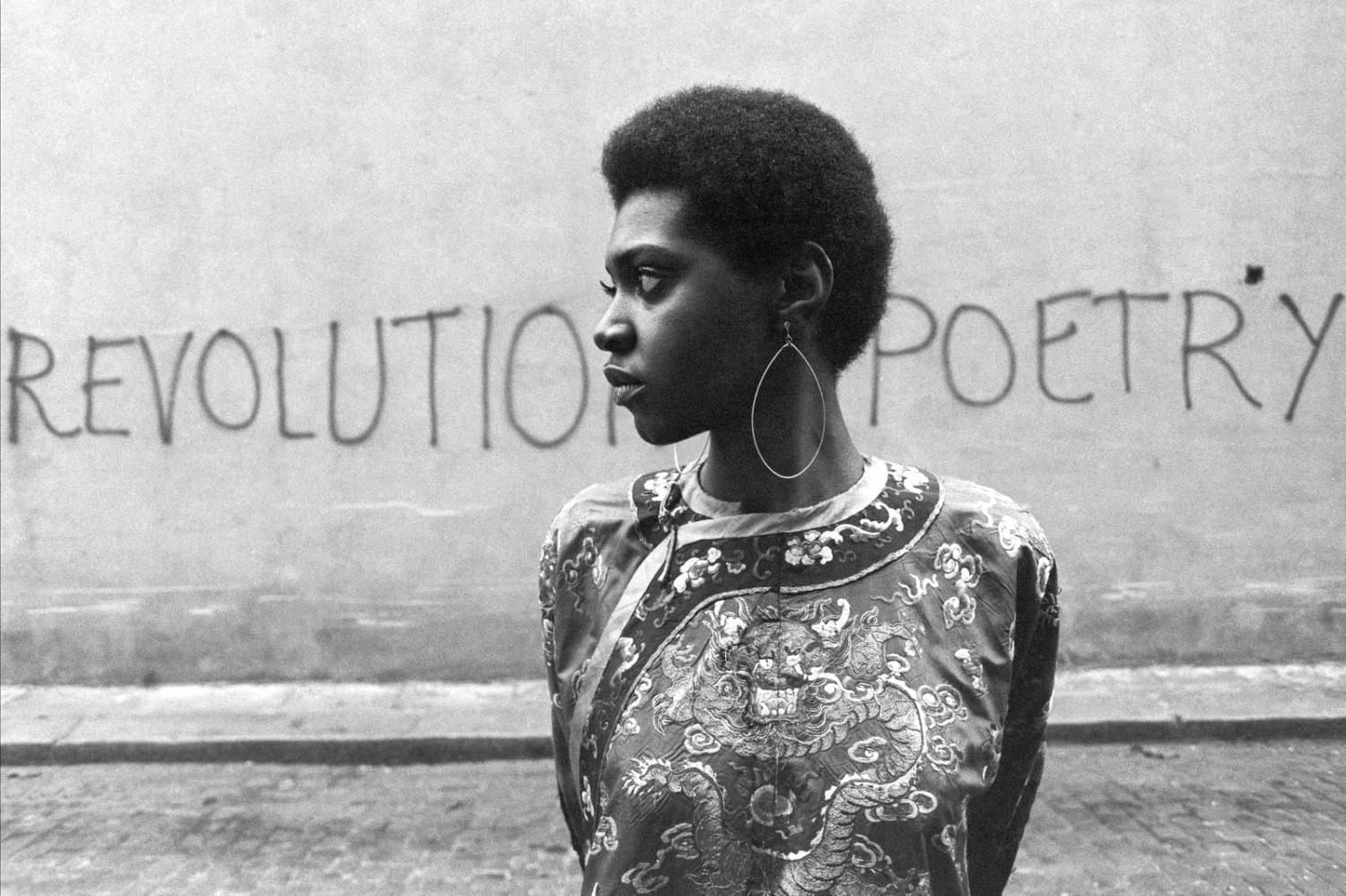

Bridging the diverse forms, strategies, activities and ambitions of protest in post-war Europe is the aim of Joachim C. Häberlen’s vibrant new book, Beauty is in the Street. His study is less about those who mounted a collective challenge to society as those who dreamt up new worlds of their own, within what the Belgian theorist Raoul Vaneigem called “the magic circle”, a space that subsisted within the “heart of every human being”, where “world and the self are reconciled”. The new horizons of utopian possibility that this furnished, Häberlen demonstrates, generated a veritable laboratory of activist experiments, manifesting themselves in movement, in sound, in subversion, in art, in violence, in sexual practice, in laughter – and even in the complete repudiation of politics itself. At its most powerful, creative activism could have thunderous effects, in 1968 bringing whole countries to a standstill, in 1989 helping to reveal the hollowness of the aged communist regimes and the pitiful inefficacy of their reflex recipe of propaganda and violence. But – and this is Häberlen’s critical point – in a myriad of less perceptible ways, too, the political and cultural energies bred in that heady cauldron of 1968 ultimately managed to transform “the society in which we live”.

It would be easy to dismiss all this as the rose-tinted reflections of a 21st century leftist. And, no doubt, it will irk some readers that Häberlen is unapologetic about the sympathy he harbours for many of his subjects. But this sympathy quickly proves to have its virtues.

Diving deeply into the history of creative activism allows Häberlen to paint a multicoloured portrait that draws together an impressively wide variety of groups: women’s movements, urban activism, anti-racism, humanitarianism, gay rights advocacy, environmentalism and even – in a perhaps curious but well-handled addition – New Age spiritualism. It also permits a subtle exploration of some of the tensions, hypocrisies and failures of these ventures, such as the uneasy but sometimes explosive alliances forged between students and workers, the evolution of left-wing activism into fully fledged terrorism in Italy and West Germany, and the striking ease with which capitalism, rather than being threatened, was simply able to adapt itself to the ideas and aesthetics of “alternative” lifestyles.

A further advantage to Häberlen’s more eclectic focus is that it takes seriously practices of protest rather than merely clustering groups and movements into amorphous masses devoid of agency or the capacity to act spontaneously. As a result, it is a book that pulses with colour and light. It brims with memorable figures and personalities such as the Dutch “Provos” of the 1960s, who distributed “an armada of bicycles”, unlocked and painted white, throughout Amsterdam; the voices behind Bologna’s anarchic “Radio Alice” station, whose professed goal was nothing less than “blowing up the dictatorship of meaning”; and Waldemar Fydrych, the leader of Wrocław’s “Orange Alternative”, which confounded the Polish communist authorities with its riotous “happenings”, often consisting of red-capped armies of dancing “dwarves”. More seriously, Häberlen’s choice of subject also permits him to peer beneath the noise and excitement of Europe’s urban centres and to shine a light on harder, “forgotten struggles”, such as the strikes launched by migrant workers in West Germany during the 1970s against discriminatory pay and workplace practices.

The catch to this kind of zoomed-in perspective is that the book at times struggles to attain a neat synthesis between the schematic and the detailed. As a result, readers looking for an exhaustive historical account of post-war protest might feel unfulfilled. One seeks in vain for a full explanatory account of the demographic, social and economic backdrop to the youthful explosion of the 1960s, for instance. There is also no space here for counter-revolutionary movements, for right-wing activism or for neo-fascist terrorism. And the geographical span of Häberlen’s study is perhaps disproportionately (though far from exclusively) West European, with France, Italy and especially West Berlin serving as its major stages.

Above all, though, this is an eminently readable book, and its individual chapters will serve as helpful entry-points for those seeking some orientation in the sometimes bewilderingly complex world of post-war European activism, in all of its cultural, political and intellectual dimensions. Along the way, it offers some historical guidance for the politics of today. The creative activism of the post-1968 era can indeed claim some echoes in contemporary European protest movements. Nevertheless, Häberlen laments, something vital “has been lost”. The age of utopia might be over, but, at the very least, Beauty is in the Street vividly demonstrates that the post-war impulse to build a better world was so much more than mere theory.