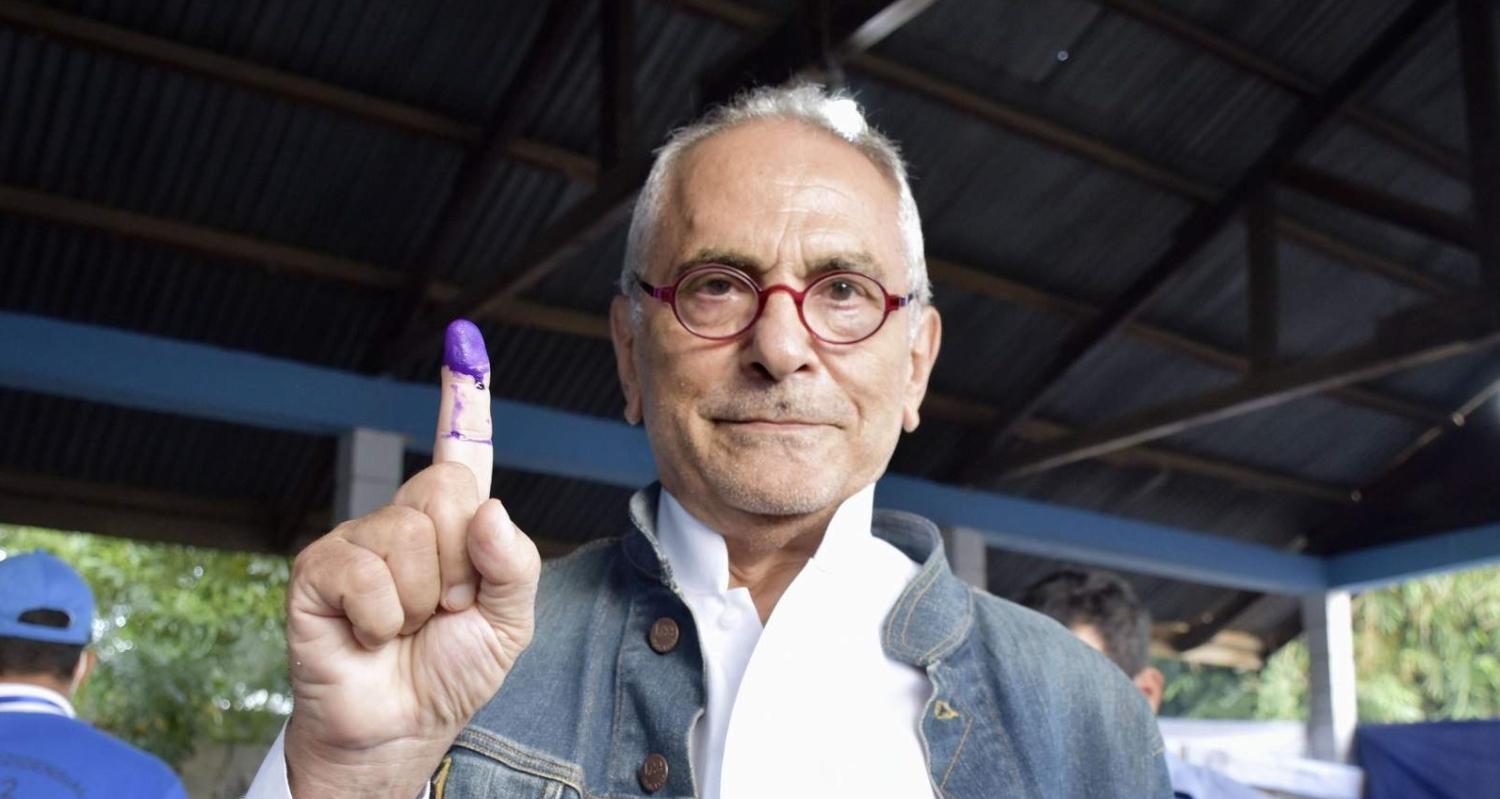

Following Timor-Leste’s presidential run-off election on 19 April, José Ramos-Horta has been confirmed as the country’s next president in a landslide victory over Francisco “Lú-Olo” Guterres. The outcome reveals a political scene still dominated by the old guard – the heroes of the independence struggle. The election campaign provided a glimpse of the rift between one-time friends in arms, while solidifying the alliance of the political parties that form the current government. Both José Maria Vasconcelos “Taur Matan Ruak” (president of Partido Libertação Popular, PLP) and José dos Santos Naimori Bukar (president of Partido Kmanek Haburas Unidade Nasional Timor Oan, KHUNTO) were campaigning for the incumbent Guterres.

Based on the last debate between Ramos-Horta and Guterres on 13 April, the focus of the presidential election was still very much on the constitutionality of Guterres’ refusal to swear-in 11 cabinet members, nine of whom were from Congresso Nacional de Reconstrução de Timor (CNRT), as well as the grounds for dissolution of the national parliament should Ramos-Horta become the next president. While the debate emphasised that maintaining peace and stability is a key role of the president, it barely touched on the daily struggles faced by the country’s population.

Based on the Poverty in Timor-Leste survey, 41.8 per cent of the country’s inhabitants lived under the national poverty line in 2014.

First is widespread poverty. Based on the Poverty in Timor-Leste survey, 41.8 per cent of the country’s inhabitants lived under the national poverty line in 2014. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) indicated that 45.8 per cent of Timorese were multi-dimensionally poor (in the areas of health, education and standard of living), and 26.1 per cent were vulnerable to multidimensional poverty in 2016. This means that the country has not done enough to improve availability and access to the three dimensions used to measure the MPI.

Second is unemployment, where the most affected sector of the population is young people. According to the country’s Analytical Report on Labour Force, the youth unemployment rate in 2015 stood at 12.3 per cent, which was much higher than the national average of 4.8 per cent. In 2020, Timor-Leste’s unemployment rate was 5.1 per cent.

Third is the education sector, which appears to be neglected and its importance for the development of the country undermined. The 2015 Census revealed that only 5.3 per cent of the population aged 15 years and older completed their university studies. On top of low educational attainment, the data also showed that unemployment among young people with university degrees was higher compared to youth who have lesser or no education. The trend is confirmed by research conducted in 2021 by João Saldanha University, which found that 48 per cent of higher education graduates were unemployed, and 35 per cent of employed graduates were actually engaged in jobs that did not match their field of study.

Lack of work opportunities has also driven university graduates and others to leave the country in search of better employment, as revealed by research into Timorese migrant workers in the United Kingdom, the seasonal worker program in Australia, and the temporary work program in Korea.

Timor-Leste’s new president must have the courage to side with the people and hold firm the vision to make the country a just and prosperous nation.

Fourth is the contrast in progress between urban and rural areas. The 2015 Census shows that urban populations have much better access to improved or safe sources of drinking water and have higher literacy rates than rural populations. Correspondingly, rural populations have higher rates of child mortality than urban populations. These types of findings reveal that Timor-Leste is far from achieving its dream of balanced development.

Under Timor-Leste’s semi-presidential system, the government – as the executive body – is in charge of development, and thus responsible for responding to the country’s challenges. However, the president is directly elected by the people and as such becomes their number one advocate, responsible for reminding the government that its ultimate obligation is to the people. Timor-Leste’s new president must have the courage to side with the people and hold firm the vision to make the country a just and prosperous nation, as stated in the Preamble of its Constitution. Although political stability is an essential prerequisite for development, improvement of people’s lives is a more enduring condition to guarantee long-term peace and security.