Australians should care about the healthcare debacle in Washington. Republicans said yesterday they still want to repeal Obamacare, but after events last week it is hard to see how President Trump and congressional Republicans can undo President Obama’s signature legislative achievement.

Regardless of whether you are interested in Obamacare, the health sector that comprises one-sixth of the US economy, or the fate of the 24 million Americans who stood to lose health insurance under the proposed Republican health legislation, last week’s spectacular Republican failure augurs poorly for Donald Trump’s presidency.

The dealmaker failed to unite his own party to do what it has promised for seven years: repeal and replace Obamacare. The bill failed in the House without even reaching the Senate. Recriminations within the divided Republican Party will continue for months.

Yet the Republican Congress will shape the agenda on core issues to Australia, including a potential US government shutdown next month, increased defence spending, and proposed cuts to the State Department and the United Nations. More broadly, President Trump will need to work with congressional Republicans to achieve legislative successes at home and therefore maintain credibility and influence abroad.

The far right House Freedom Caucus stared down a Commander in Chief who charmed and threatened individual congressmen. Similarly, many moderate House Republicans refused to support an unpopular bill that was likely to hurt their prospects in the 2018 midterm elections.

Perhaps the bill’s failure is unsurprising. President Trump has a limited understanding of Congress. He seems naïve to the complex, messy deal making required to pass legislation.

Governing is much harder in the US than Australia. Whereas an Australian Prime Minister can typically be assured of the support of their entire caucus in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, a US president and his lieutenants in Congress – like Frank Underwood in season one of House of Cards – must work feverishly to ‘whip’ votes on Capitol Hill. Congress is never a rubber stamp for any president, even when the president’s party controls both the House and the Senate.

Nonetheless, the healthcare implosion is a timely reminder that the Republican Party is deeply divided. Donald Trump hijacked the party in last year’s primaries. Trump’s nationalist, populist platform is fundamentally different to the establishment Republican conservatism of House Speaker Paul Ryan.

Yet it is still remarkable that a disparate group of at least 30 little-known House Republicans bucked President Trump and Republican congressional leaders on the very issue that was their foremost rallying cry throughout the Obama presidency.

Many Republicans in Congress blame Ryan, the author of the healthcare bill, for its failure. If Ryan stumbles on other legislation he could well suffer the same fate as his predecessor John Boehner, who resigned the Speaker’s gavel because he was unable to keep the Republican Party together.

Democrats will be emboldened. The Democratic base demands ‘resistance’ to Trump’s agenda. Noisy and united Democratic opposition to Trump's healthcare bill made it deeply unpopular in the electorate. Democrats need their base to be angry with the president and turn out en masse in 2018 if they are to have any hope of reclaiming either the Senate or the House and thereby regaining some formal power in Washington.

Failure on healthcare makes it almost certain that President Trump will not have a major legislative achievement in his first 100 days in office. And it bodes ill for the United States’ place in the world under the 45th President.

On both healthcare and international issues, Trump’s bark appears worse than his bite.

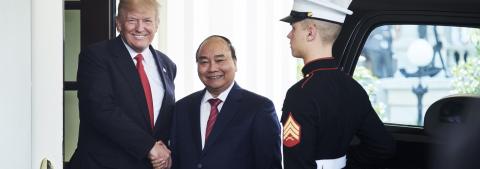

He badgered, bragged, and abruptly ended his infamous phone call with Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, yet the refugee deal remains alive and US officials are vetting people on Manus Island and Nauru. Trump refused to confirm his support for the One China policy for months, before doing just that with President Xi Jinping and then inviting him to a summit in Florida.

Xi may arrive at the ‘winter White House’ next week thinking Trump is weak. Any perception of weakness is dangerous for stability in Australia’s region, because Xi may want to test whether Trump means what he says on issues such as the South China Sea, the US-Japan alliance or North Korea.

Additionally, no president can be effective internationally if he is hamstrung by fundamental problems at home. A shutdown of the US government next month is possible. Congress faces a 28 April deadline to pass a spending bill to keep the government running. And congressional votes on the State and Defense Department budgets will determine the extent to which Trump reshapes US international engagement away from diplomacy and multilateralism, towards a military-first approach.

Some say that all foreign policy is domestic politics. If Trump can’t get a handle on Washington’s politics – not least the requirement to work with Congress – US foreign policy will suffer, and Australia will not escape the consequences.