The United Kingdom’s proposed “tilt” to the Indo-Pacific was met with plenty of scepticism, including from this author, when it was unveiled in March as part of a broader Integrated Review of defence and foreign policy.

Politicians and foreign policy analysts tend to obsess about nomenclature. But catchy buzzwords can obscure as much as they elucidate. My first principle of analysis is to ignore the rhetoric and look at the reality.

In this case, how is a post-Brexit UK that has been battered by the pandemic going to find the time and resources to focus on a part of the world that is distant in geography and values?

Southeast Asia was always going to be a key proving ground of the UK’s ability and willingness to become a more influential actor in the Indo-Pacific.

The contours of the UK’s relationships with allies and close partners such as Japan, Australia and South Korea are already well established, while the deteriorating direction of the UK’s relationship with China is also increasingly clear.

Southeast Asia, at the geographical heart of the Indo-Pacific, is the sub-region where there is most to play for, and most at stake, for the United Kingdom and others looking to balance China’s growing power and influence.

That is why the British government made its bid to become a formal dialogue partner of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) one of the key objectives in the Integrated Review.

The vote for Brexit in 2016 meant that the United Kingdom would lose its seat at the ASEAN table as part of the European Union.

Earlier this month, ASEAN approved that application, ending a 25-year moratorium on new dialogue partners, and putting the United Kingdom in the same rank as Australia, Canada, China, the European Union, India, Japan, New Zealand, Russia, South Korea and the United States.

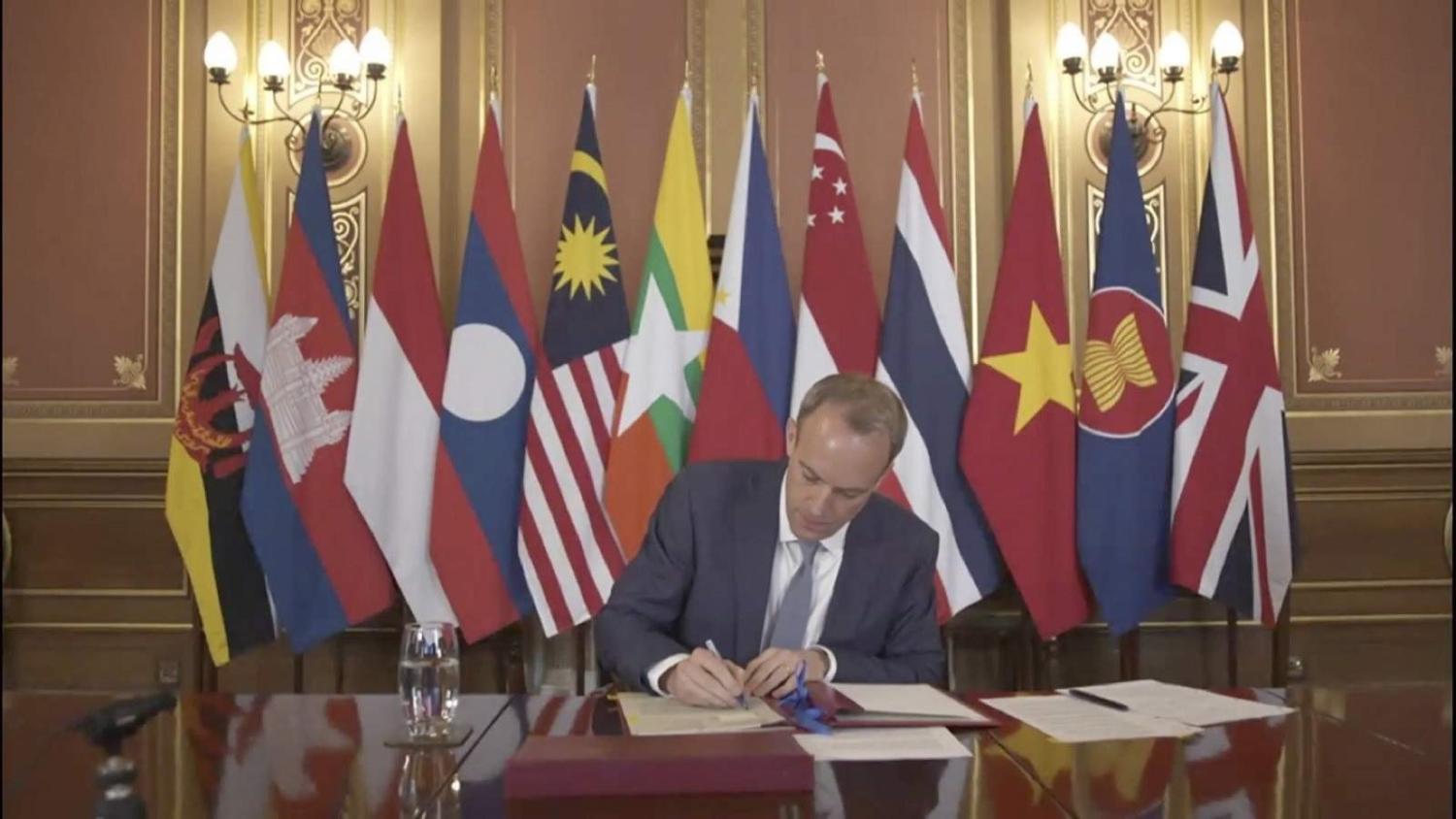

It was a something of a personal victory for Dominic Raab, the British foreign secretary, who has visited Southeast Asia five times in the two years since he took the job. More importantly, it was the culmination of the sort of intense diplomatic ground game that will be vital if the United Kingdom is to capitalise on its new enhanced status within ASEAN.

Although it would not have been on the minds of many British citizens, the vote for Brexit in 2016 meant that the United Kingdom would lose its seat at the ASEAN table as part of the European Union.

From the British government’s perspective, securing an independent, high-level relationship with ASEAN was one way of showing the naysayers that Brexit would not mean the United Kingdom shrinking from the world stage.

However, there was reluctance in both London and Southeast Asian capitals. Some British officials doubted the utility of more formal engagement with an organisation that is often criticised for holding too many meetings, taking too few decisions, and being susceptible to meddling from Beijing. Some Southeast Asian officials questioned Britain’s real commitment to the region, and were wary of further jamming the packed ASEAN agenda.

The United Kingdom learned the quirks, advantages and pitfalls of engaging with ASEAN at an institutional level by setting up a dedicated ASEAN diplomatic mission in Jakarta in 2019, one of only two established by non-dialogue partners (the other being Norway).

It was no mean feat to persuade the ASEAN member-states to sign off on the UK’s new status, particularly at a time when the British government has been implementing tough sanctions on the Myanmar junta, which controls the country’s foreign ministry and therefore has a de facto veto on all ASEAN decisions.

The question now is: what next?

It is easy to paint this as a largely symbolic victory for Britain. As one veteran Indonesian diplomat joked to me, why would anyone lobby to get access to ASEAN meetings when we all wish we could get out of them?

From Washington to Canberra, Western officials have a history of rediscovering Southeast Asia only to lose interest when the going gets tough.

But the symbolism does matter. The UK government wants to show it is committed to multilateral engagement outside the European Union. For ASEAN, the UK’s enthusiasm to secure a dialogue partnership underlines the organisation’s importance as an anchor to the broader Indo-Pacific architecture.

Moving forward, Britain should use its new position as a foundation for increased regional engagement across the economic, security and development domains. From education and finance to defence and counter-terrorism, the United Kingdom has much to offer Southeast Asia, as well as much to gain from enhanced trade, political and military linkages.

The United Kingdom will need to work harder bilaterally in Southeast Asia, as well as through the many ASEAN mechanisms. It should also use its ASEAN platform to intensify collaboration with other like-minded external partners in Southeast Asia, including Australia, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea and the United States.

Britain’s renewed focus on Southeast Asia has broadly been welcomed in the region, from a first trip by a foreign secretary to Cambodia in 68 years, to the first-ever visit by a defence secretary to Vietnam. But, from Washington to Canberra, Western officials have a history of rediscovering Southeast Asia only to lose interest when the going gets tough.

The challenge for the United Kingdom is to maintain the diplomatic energy and the pace of high-level visits as ministers realise the difficulties, as well as the delights, of dialogue with ASEAN.