In the 1950s, an unlikely friendship grew between US medical researcher Albert Sabin and Soviet microbiologist and virologist Mikhail Chumakov. Their mutual trust and esteem resulted in a US developed vaccine against crippling polio being tested on millions of people in the Soviet Union. Notwithstanding the suspicions of the Cold War, the successful project was considered an early case of vaccine diplomacy and scientific collaboration, a first step in the eradication of the disease from all but two countries in the world.

History can offer salutary lessons. With vaccination against Covid-19 ramping up globally, the distribution of vaccines has again become a mechanism of geopolitical influence.

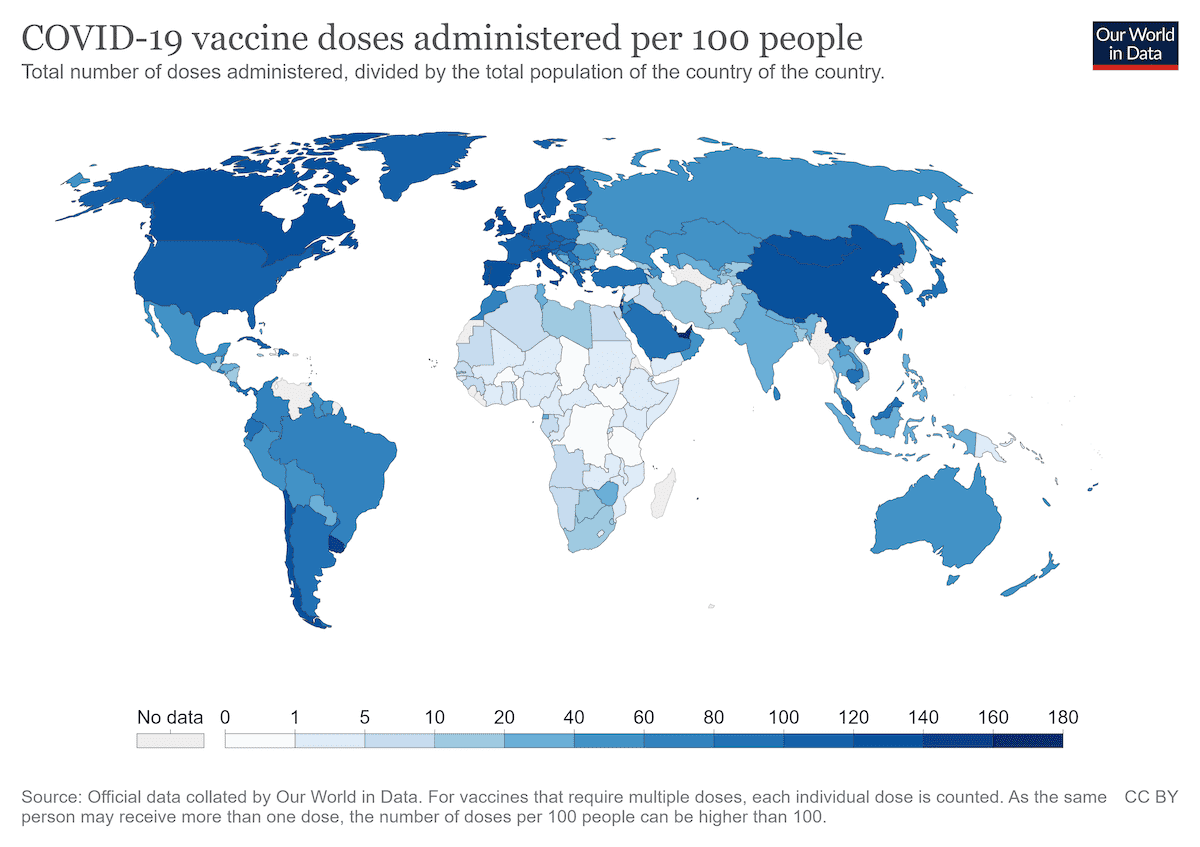

Yet it is uncertain whether Covid vaccine diplomacy will have such a happy ending. Home to more than half of the world’s population, poorer nations have received only 20% of the 4 billion vaccine doses that have been issued globally. Demand is so great that in August the World Health Organisation called for a moratorium on giving out booster shots in rich countries until at least September, saying it was necessary to free up supplies to allow at least 10% of the population of each country to be vaccinated. The World Health Organisation Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said, “we cannot accept countries that have already used most of the global supply of vaccines using even more of it, while the world’s most vulnerable people remain unprotected”.

Recognising the negative epidemiological, financial and health impacts of an unrestrained pandemic in poorer regions has led organisations such as UNICEF, Doctors without Borders and the Wellcome Trust to redouble their efforts for global vaccine equity. They argue persuasively that reducing the number of infections worldwide is the only way to prevent the emergence of new mutations such as the Delta variant of Covid19, which is more contagious than the original version and more resistant to some vaccines.

By contrast with many rich countries, which prioritised vaccinating their own populations, China and Russia have from the outset used donations and low-cost sale of vaccines made in state-owned or state-influenced companies as a foreign policy tool. Their motives have been attributed to reducing the impact of the epidemic in their regions and to find new opportunities and influence. These efforts initially had at least short-term success, as Sinovac and Sinopharm from China became the world’s most used vaccines.

Against the backdrop of surging case rates, there have been supply issues with some of the principal regional producers of the vaccine.

There has been some concern in the media about the transparency of the data supporting the vaccines produced in China and Russia. But Sinopharm and Sinovac have both been granted WHO emergency use listing and the global vaccine alliance GAVI has signed an agreement for supply of more than 100 million of these vaccines to COVAX, which aims to provide equitable access to vaccines worldwide. Importantly, in July, one of the world’s most prestigious academic journals Nature published an article defending Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine as safe.

Urgent demand

At present almost all countries in Southeast Asia are struggling to repress a tidal wave of infections caused by the Delta variant of Covid19. Case rates in Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam are growing exponentially. Already Indonesia has recorded almost 120000 deaths from Covid-19. This is affecting the regional economy and putting catastrophic pressure on national health systems. Indonesia has primarily used the Sinovac vaccine but fewer than 10% of its population of 270 million have received two doses. Many vaccinated health professionals have caught the virus and some have died, leading to widespread doubts about the efficacy of Sinovac, which is further fuelling vaccine hesitancy. Indonesia is now urgently trying to supply booster shots of the Moderna vaccine to health professionals.

Against the backdrop of surging case rates, there have been supply issues with some of the principal regional producers of the vaccine.

In July, Thailand was reported to be considering both joining COVAX and purchasing additional Sinovac vaccines to fill a glaring supply gap. Siam Bioscience, the regional manufacturing facility for the Oxford University jointly developed AstraZeneca, had struggled to meet supply targets. This delay has affected Thailand, which has ordered 61 million doses, as well as neighbours Philippines and Vietnam who are depending on up to 119 million doses from the same facility at a time when only 1.12% of the population of Vietnam is fully vaccinated. In July, AstraZeneca issued a press release stating they were “scouring the 20+ supply chains in our worldwide manufacturing network to find additional vaccines for Southeast Asia, including Thailand”. The delay in production has led the Thai government to consider imposing an export ban on existing supply, resulting in claims of regional “vaccine protectionism”.

Adding to Australia’s already excessive cache of vaccines in stock … Australia has been scouring global distribution networks looking for surplus vaccines of Pfizer.

There is an imperative to act now before the situation worsens. A study by the International Monetary Fund found that conflict and insecurity increased after past viral outbreaks including SARS, H1N1, MERS, Ebola, and Zika, particularly in countries with high levels of inequality or where the health consequences increased poverty.

Indeed, Australia’s foreign vaccine program is titled the regional Vaccine Access and Health Security Initiative – an indication that the government may be concerned by the security implications of the pandemic as well as the cost to human health.

What more Australia could do

Australia’s geographic position in the Indo-Pacific region and abundance of vaccines mean it could do more to support other countries. Its total domestic order of 169 million doses is enough to vaccinate everyone in the country over the age of 14 almost eight-and-a-half times. Adding to Australia’s already excessive cache of vaccines in stock, in production or on order, the Australian Financial Review recently reported that Australia has been scouring global distribution networks looking for surplus vaccines of Pfizer. Last week it received an additional 200,000 doses, offering to pay a premium to sellers. One million Pfizer doses have been obtained from Poland over the weekend. These actions could raise the prices of some of these vaccines, making them more unaffordable for poorer countries.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners recently published an article suggesting Australia’s surplus should be donated to countries in the Pacific and Southeast Asia that are struggling with outbreaks of the Delta variant of Covid. The Burnet Institute’s Michael Toole has called for Australia to deliver more AstraZeneca direct from its Australian manufacturing facility to close neighbours such as PNG and Indonesia.

Changing health advice now encourages Australians over 18 to consider taking an AstraZeneca vaccine, which should increase domestic demand for the 1 million AstraZeneca vaccines which are being produced every week at a CSL facility in Melbourne. But there is no doubt the country will have surplus doses once new shipments of Pfizer and Moderna arrive and if the 51 million Novavax doses on order are approved by authorities.

And Lowy Institute polling suggests a high level of public support for assisting the region, albeit that help for Pacific Island nations is favoured more than to Southeast Asia.

Australia’s commitments

As a producer country and member of the G20, Australia has an important role to play. Australia’s first contribution to vaccine equity was an $80 million contribution to COVAX, the global effort which aims to provide enough doses to allow all participating countries to vaccinate at least 20% of their population, regardless of income levels. The 20% target is based on reasoning that it is better to vaccinate a proportion of people in every country than all in one country and no one in the next, as inequality in vaccine distribution undermines the effort to end the pandemic as a whole. Australia has since increased its contribution to $130 million.

Australia has also offered $623 million over three years through two other initiatives, $523.2 million for doses and technical support through the Vaccine Access and Health Security Initiative for neighbouring countries and an additional $100 million through a Quadrilateral Security Dialogue partnership with US, India and Japan. At the G7 Summit in June, Australia also made a commitment to share a further 20 million doses with the Pacific and Southeast Asia by mid-2022.

The decision of where to allocate vaccines shows an appreciation of the vulnerabilities in Australia’s region and a responsiveness to the way it has been affected by the Delta variant of the disease. But the contribution, set out in the table below provided by the Department of Health, clearly pales in comparison with Australia’s massive horde at home of 169 million doses – much of which we may not be able to use.

Delivered doses from Australia as at 30 July 2021

| Country | Total |

|---|---|

| Papau New Guinea | 28,470 |

| Timor-Leste | 277,850 |

| Fiji | 561,000 |

| Solomon Islands | 63,000 |

| Tuvalu | 7,000 |

| Samoa | 50,000 |

| Tonga | 9,000 |

| Vanuatu | 20,000 |

| Total | 1,016,320 |

While the idea of sending unused vaccines overseas is compelling, countries have to be ready to receive vaccines. This involves refrigeration for storage, as well as transport for distribution, and health professionals to administer the vaccines.

The risk is wastage. The ABC has reported a COVAX donation of 130,000 AstraZeneca doses expired last month in Papua New Guinea and thousands will be destroyed having past a consignment date. About 100,000 people have received the vaccine in PNG, about 0.6% of the population.

A spokesperson for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade confirmed that Australia is timing the delivery of doses to recipient countries to best coordinate with their own national vaccine roll out strategies, which will include logistics, storage and resources. While each country will need to procure vaccines based on need and urgency, in the future it may also make sense for countries with distribution challenges or remote populations be prioritised for the one shot vaccines, such as the Johnson & Johnson type, or those currently in development by Vaxart, which can be taken by tablet.

The importance of COVAX

Vaccine diplomacy is not straightforward. When Australia recently donated additional doses of AstraZeneca to PNG, it was accused by China of making a self-interested diplomatic point by creating competition with China’s Sinopharm vaccine. Increasing Australia’s donations to COVAX could be one way around some of these thorny diplomatic and logistical issues.

Up to 30 July, COVAX has supplied 177 million vaccines to 138 participating countries. However, COVAX has also reported a shortfall of 190 million vaccines and pleaded with the G7 in an open letter to commit more doses. In August WHO called for all vaccine producers around the world to prioritise COVAX for contributions and requested support from the G20 to help reach its global vaccination targets.

A key reason why COVAX may be the most attractive way for Australia to contribute to vaccine equity – and repress Covid19 – is because of its commitment to neutrality. The doses of vaccine and support to provide them will be distributed based on need. This should prevent uncontrollable outbreaks that may lead to new variants. By preventing new mutations these interventions will benefit all countries, because there is no guarantee that even vaccinated populations will be protected from new mutations of the disease. COVAX attempts to shape global vaccine markets to improve long term vaccine affordability for poorer countries. While recent media reports have been critical of Australia’s decision to take 500,000 Pfizer doses from COVAX, the decision to supply doses to rich countries may be an effort to control escalating prices for these vaccines. Australian government vaccine donations may provide some benefit to recipient countries, yet this benefit could be undermined if willingness to pay a premium for surplus doses drives up prices globally.

One US National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper estimated that inequitable global vaccination rates in 2021 would leave wealthy countries to bear up to 49% of global losses from the pandemic, up to US$5 trillion. This cost to the rich is regardless of their own vaccination rates.

While Australia should increase its planned commitment to COVAX, given the urgency of the need in some parts of the Indo-Pacific region, it can also continue allocating surplus vaccines as they arrive, are produced or approved to countries in urgent need. The WHO message can’t be repeated enough, “with a fast moving pandemic, no one is safe unless everyone is safe”.