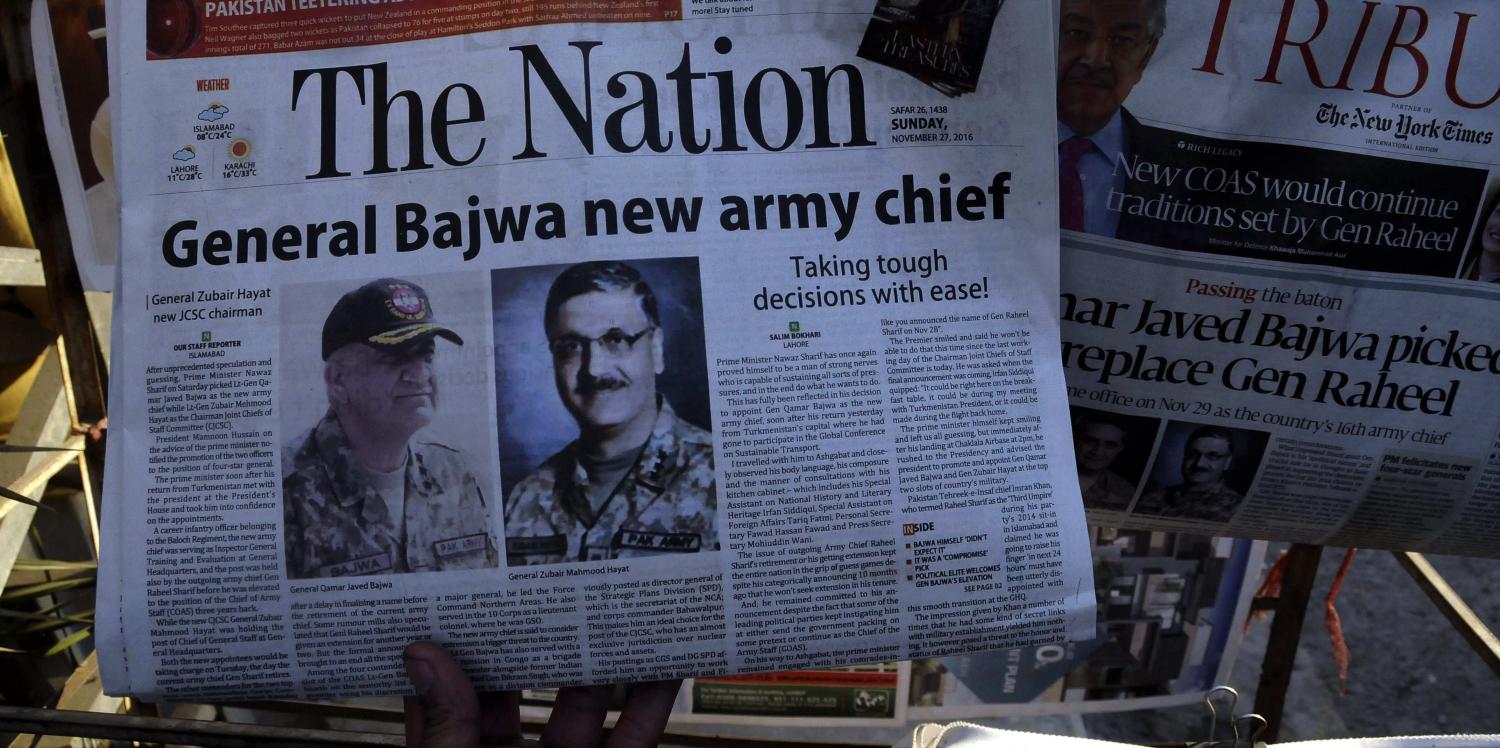

On Tuesday, General Qamar Javed Bajwa succeeded General Raheel Sharif to become Pakistan’s chief of army staff (COAS). Bajwa was the dark horse in the race, superseding four generals (including the reputed favourite) to reach the top job. This is not unusual: setting aside the first two Britons in the job, only four of Pakistan’s fourteen army chiefs were the most senior officers at the time of their elevation. No doubt helping his case, Bajwa was said to be a voice of restraint during the anti-government sit-in of 2014, when other senior officers reportedly wanted to intervene against the government. But whether or not this is true, we should be wary of taking these early profiles too seriously.

History is a useful guide here. Bajwa, we are assured, is ‘an apolitical person’, ‘more reserved than his predecessor’, and a ‘thorough professional’. If this language sounds familiar, it’s because it’s the stock greeting for a Pakistani army chief – more in hope than in expectation:

- In 2013, General Sharif was described as ‘apolitical’ and a ‘straight-talking professional with no political ambitions’. It didn’t quite turn out that way, with the army channeling popular protests to apply pressure on the government, and nurturing a cult of personality around Sharif himself. As Mosharraf Zaidi notes with wry understatement, Sharif ‘certainly did a fair bit more than only soldiering’.

- In 2009, General Ashfaq Kayani was ‘seen as largely apolitical’ and ‘a demure professional’. He went on to slap down the civilian government repeatedly over nuclear doctrine, judges, control over the ISI intelligence agency, Osama Bin Laden’s presence in Pakistan, and a diplomatic scandal known as ‘memogate’.

- In October 1998, General Pervez Musharraf, in the month of his appointment, stressed his own ‘apolitical’ credentials – before unilaterally launching a war, overthrowing the government (then, as now, led by Nawaz Sharif) in a coup the subsequent year, and ruling for just under a decade.

So, when a Pakistani civilian hears the word ‘apolitical’, it’s a good idea to change the locks.

Since the formal restoration of civilian rule in 2008, the balance of power between elected civilians and ambitious generals has been fluid. Though security policies (nuclear weapons, India, Afghanistan, and most foreign policy) have never budged from military hands, the informal balance of power shifted briefly towards civilians in 2011, after the army was humiliated by the US raid on Bin Laden, and then again in 2013, when elections led to Pakistan’s first ever successful transition from one elected government to another. That summer, the newly elected Sharif even pushed for a treason trial of his old nemesis, Musharraf.

But these moments of civilian assertiveness have been short-lived. As I explained in these pages in September, General Sharif steadily expanded his and the army’s power through what came to be called a ‘soft coup’, capitalising on political scandals and protests tolerated and encouraged by the army, and on Sharif’s very real successes in fighting the Pakistani Taliban and curbing violence in Karachi. A recent surge in India-Pakistan tensions following attacks by Pakistan-backed terrorist groups on Indian soldiers, an Indian reprisal raid, and intensified shelling, are also likely to reinforce the army’s power, as are security concerns around Chinese investments in Pakistan.

Bajwa, therefore, inherits a relatively strong institutional position, with the army able to project itself as a scourge of corruption, a robust shield against Indian aggression, and guarantor of the all-weather alliance with Beijing at a time when US-Pakistan ties are deeply frayed. Civilian rule is taking hold on the surface, but civil-military tensions swirl beneath.

With respect to India-Pakistan tensions, Bajwa’s career path may be relevant. From 2013 to 2015, he was commander of the army’s X Corps, which plays a prominent role on the increasingly turbulent Line of Control (LoC) with India. It was during his tenure there that the ceasefire on the LoC came under extreme stress, with a series of abductions, beheadings, and other confrontations between India, Pakistan, and Pakistan-backed militants. Bajwa had also previously served with X Corps twice in more junior roles, during calmer times, as well as heading up the Force Command Northern Areas, which is responsible for other sensitive parts of the LoC (including the disputed Siachen glacier). Notably, Bajwa served under former Indian Army Chief General Bikram Singh as part of UN peacekeeping operations in the Congo in 2007. Singh has praised Bajwa as ‘totally professional and outstanding’, and noted he is ‘well-versed with the complexities, nature of operations and terrain along the LoC’.

Some press reports note that Bajwa has said he views internal threats as more pressing than that from India. However, this was also true of Kayani and Sharif, with little concrete impact on their substantive positions towards India. For its part, the Indian government has taken a guardedly agnostic position: ‘we cannot assume that things will go worse or get better. The reading is that he will pursue the same policies’. Rana Banerji, formerly a Pakistan specialist at India’s foreign intelligence agency, suggests that Bajwa ‘may keep a non-controversial, low profile to begin with’. But as attacks on Indian Army personnel continue, the new chief is likely to have to make a decision as to how much to reign in militant groups operating on the LoC, and whether to handle another Indian raid, should it come, in the same way as Sharif did.

Finally, it is worth noting that Bajwa’s appointment came despite a vicious, sectarian campaign against him (led by a senior politician) on the basis that one of Bajwa’s relatives was a follower of the Ahmadiyya sect, which has been persecuted in Pakistan and abroad. Since the 1980s, Pakistani law has prohibited Ahmadis from referring to themselves as Muslim, and terrorist groups have often targeted the community. And yet, several Ahmadis have served with distinction in the Pakistan Army. It is creditable that this campaign did not hinder Bajwa’s appointment, during a time when Pakistani sectarian groups with close ties to terrorists are finding space in the political mainstream.

Photo: Getty Images/Pacific Press