The notion that tackling investment and infrastructure shortfalls is essential to lifting growth, job creation and productivity is now familiar rhetoric.

It's a point made regularly by the heads of international organisations like the IMF, World Bank and OECD and also often found in G20 communiques. Australia has even seen an 'infrastructure prime minister' come and go.

A recent report by the McKinsey Global Institute, 'Bridging global infrastructure gaps', explains why economic policymakers have needed to make investment such a central issue in recent years. Public investment across the majority of G20 economies, and most advanced economies, declined as a share of GDP following the global financial crisis. [fold]

A key takeaway from the report is that the world has an infrastructure funding challenge that governments aren't addressing by themselves. Ambition needs to be lifted to fill infrastructure funding gaps.

To provide a sense of scale, McKinsey estimates the world needs to add the princely sum of $350 billion to the annual $2.5 trillion invested in transportation, power, water and telecom systems if it is to address infrastructure deficits and meet needs by 2030. Even more would be needed if governments are serious about delivering on the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The good news is that there are a range of suggestions for ramping up funding from the public sector and institutional investors, making better use of funds, and making better use of existing projects.

So policymakers should just get to ploughing more money into projects, right? Not so fast.

As the Grattan Institute's Marion Terrill and Brendan Coates have argued, the conventional wisdom about infrastructure deficits may not be so wise.

One big problem is determining what an 'infrastructure deficit' actually is. McKinsey uses a very rough rule of thumb to underpin its analysis. The report notes the value of infrastructure capital stock in 20 countries between 1992 and 2012 averaged around 70% of GDP. It then assumes that the optimal value of infrastructure capital stock across all countries, including Australia, will be 70% of GDP.

It would be highly unfair to single out McKinsey's methods here. As Terrill and Coates point out, other top-down assessments are plagued by similar problems, and the range of estimates for Australia alone varies by hundreds of billions of dollars. What is more, the alternative, 'bottom-up' approaches (which add up the value of identified projects to reach an aggregate national number) need to make simplifying assumptions too, such as thinking all projects in a given list of potential projects should be funded irrespective of economic or social feasibility.

But the flaws in methods for calculating aggregate infrastructure deficits, combined with IMF and World Bank research in recent years that questions the merits of simply increasing spending on infrastructure, suggests that policymakers shouldn't be driven by headlines about supposed infrastructure deficits. The focus should instead be on prioritising the 'right' investment. Picking the right projects is a tricky beast and raises a complex array of questions. Fundamentally, investment is only economically desirable if the benefits of extra projects outweigh the costs they impose on the community, including all social and environmental costs.

What's more, countries must also work out the best additions to existing infrastructure networks. For example, the Australian Infrastructure Plan acknowledges the majority of infrastructure Australians will use in the next 15 years has already been built, but concludes this infrastructure will require substantial additional funding for maintenance, renewal and upgrade in line with population growth.

Part of the story then is about improving the quality of the cost-benefit analyses underpinning projects. Oxford's Bent Flyvbjerg and Harvard's Cass Sunstein have found that conventional cost-benefit techniques tend to overestimate benefit-cost ratios by typically between 50% and 200%, depending on the type of project. These errors cost billions.

Other questions need to be asked about whether broader macroeconomic, financial and taxation policies impede projects, as well as of the nature of institutions governing the project selection process.

As Mike Callaghan has argued though, what matters most is that all significant factors influencing a decision are accounted for, fully disclosed and available for public scrutiny.

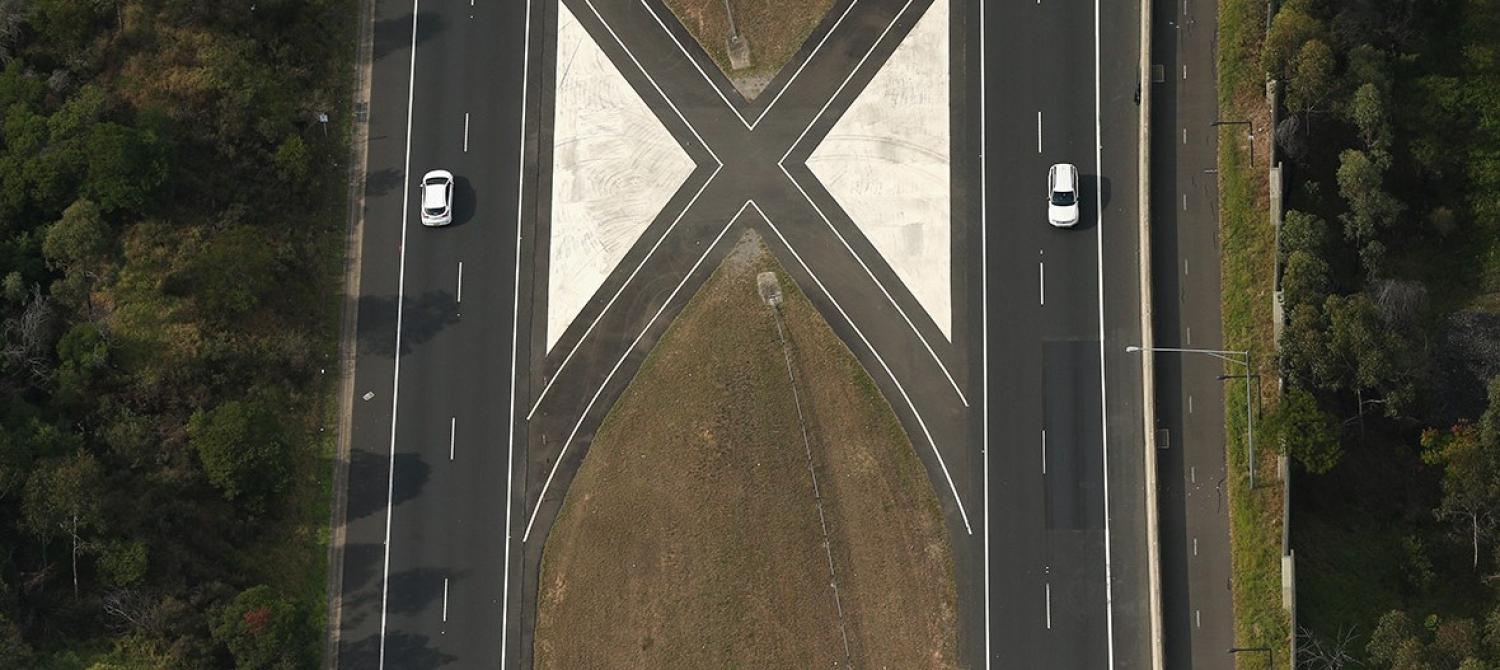

If governments are looking for new actions on investment, they should consider a commitment to make the selection of infrastructure projects fully transparent. As the McKinsey report points out, there are also significant gains to be made by making a public priority of maintaining existing infrastructure. Perhaps it is also time to revist an old policy chestnut of improving price signals, such as through road user charging.

Photo: Getty Images/Cameron Spencer