The Bougainville referendum and beyond

As Bougainville prepares for a referendum on independence, Australia must navigate a policy response that acknowledges the history of conflict and colonialism there, Bougainville nationalism, PNG sensitivities, the principles of the guiding Bougainville Peace Agreement and new geostrategic realities to help forge a lasting solution.

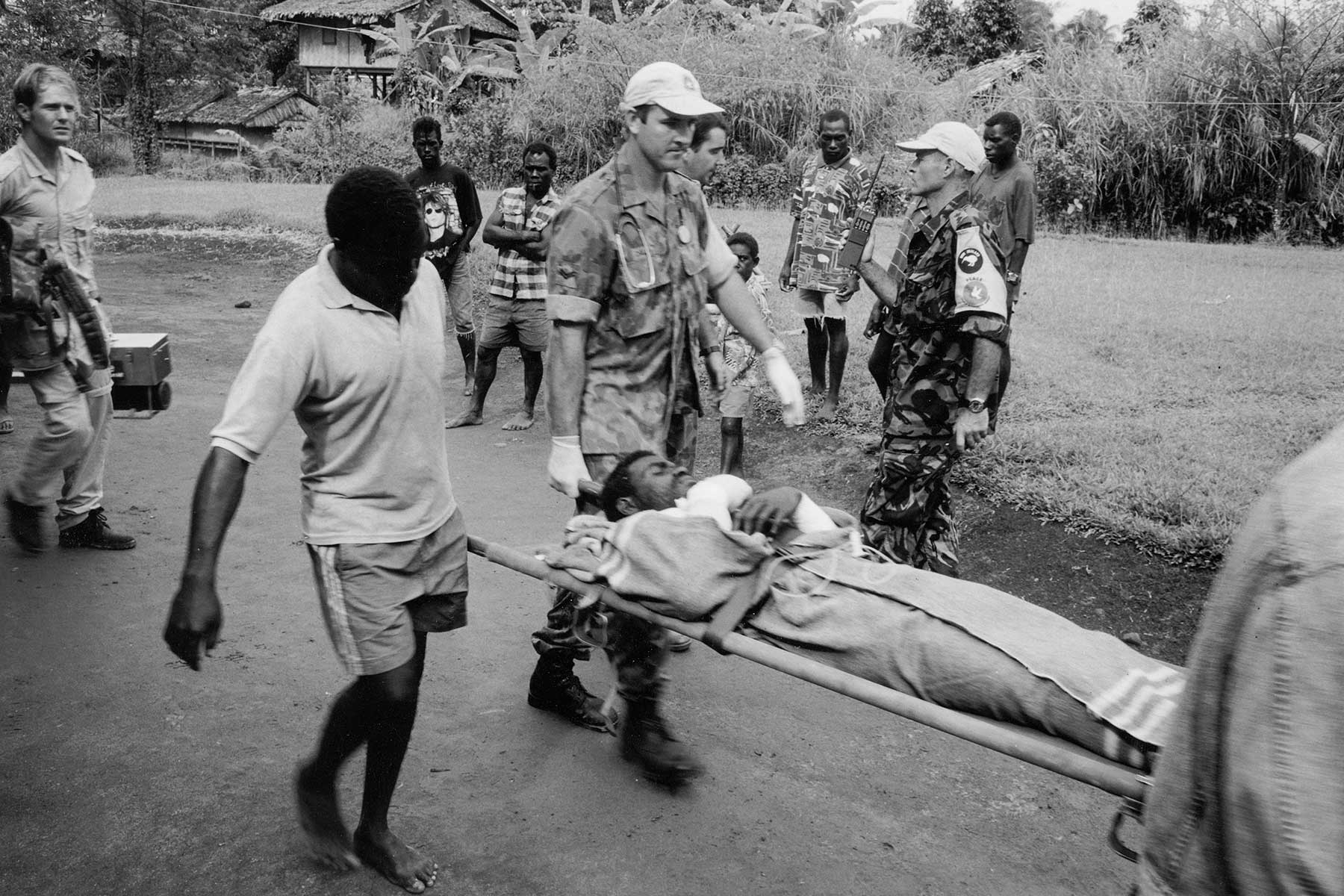

Photos copyright Ben Bohane/Wakaphotos.com

- Bougainville is largely ‘referendum ready’ and its people are expected to vote overwhelmingly for independence in the November referendum.

- While Bougainville has abundant natural resources and a skilled older generation, as an independent nation it would face many challenges including fiscal self-reliance, consensus on mining issues, unity and political integrity.

- Australia has a significant stake in the outcome and should step up its engagement to remain a trusted peace and security broker in Melanesia. It should not oppose Bougainville’s independence if that is the result under the referendum and peace process, and should take a leading role in ensuring a peaceful resolution between the parties.

Executive Summary

Australia has a long history and a complicated relationship with Bougainville, an island group to the east of the PNG mainland that was administered by Australia as part of Papua New Guinea for 60 years between 1915 and 1975. On 23 November 2019, its 300 000 people will commence voting in an independence referendum, and a clear majority is expected to vote for independence from Papua New Guinea. The Bougainville Peace Agreement requires PNG and Bougainville to negotiate an outcome after the conclusion of the referendum, and Canberra has indicated that it will respect any settlement reached between them. James Marape, the new PNG prime minister, has expressed a clear preference for an autonomous, not independent, Bougainville.

With geostrategic rivalry growing across the Pacific, Australia will need to step up its engagement and consider further policy approaches to Bougainville if it wishes to remain a trusted peace and security broker in Melanesia. If the people of Bougainville vote for independence and are unable to reach agreement with the government of Papua New Guinea, the Bougainville issue may precipitate another regional crisis.

Introduction

On 23 November 2019, Bougainvilleans will commence voting in a long-awaited referendum to decide whether they wish to stay part of Papua New Guinea or become an independent nation. In a process that will take place over two weeks, voters will be asked whether they want Bougainville to have either “greater autonomy” or “independence”.[1] This is the culmination of a 20-year peace process which followed the end of a ten-year war on Bougainville that was the most intense conflict in the Pacific since the Second World War. The principles of the truce, enshrined in the Bougainville Peace Agreement (BPA) signed in Arawa on 30 August 2001 which formally ended the war, remain the primary framework to create a lasting peace. The three main pillars of the agreement were the creation of the Autonomous Bougainville Government (ABG), which occurred in 2005; weapons disposal; and the referendum, to be held no later than 15 years after the formation of the ABG (that is, by 2020).[2]

Based on current sentiment in Bougainville, it appears a majority of Bougainvilleans — perhaps three-quarters or more — will opt to vote for independence.[3] This is being driven by a range of factors: their long-standing sense of separate ethnic identity from PNG, residual animosity after the war years, a perceived failure of the current model of autonomy, and reservations about its future as part of PNG.

While the referendum may be a high point for the people of Bougainville, it is not the end point. Under the BPA, the vote outcome must be ratified by PNG’s national parliament and a “negotiated outcome” then struck between the PNG Government and the ABG.[4] An independent agency — the Bougainville Referendum Commission (BRC) — was formed in 2017 to conduct the referendum, overseen by a Joint Supervisory Body (JSB).

Australia has a significant stake in the outcome of the November referendum. Bougainville’s war between 1988 and 1998 cost an estimated 10 000–15 000 lives[5] and presented a major security challenge for PNG, Australia and their immediate neighbours. Australia financed and provided personnel and logistics for several major peacekeeping operations on Bougainville over the years, beginning with a short-lived South Pacific Regional Peace Keeping Force (SPRPKF) in 1994 and finishing with a Truce Monitoring Group (TMG) and its successor, the Australian-led Peace Monitoring Group (PMG), which withdrew from Bougainville in 2003. These were significant operations involving military deployments that cost Australia hundreds of millions of dollars.[6]

Australia’s initial peacekeeping missions in Bougainville in the mid-to-late 1990s were arguably the most substantial Australian missions since Vietnam and presaged later Pacific interventions in Timor-Leste and the Solomon Islands. New Zealand also played a major role, leading the TMG and brokering peace agreements such as the Endeavour Accords in 1990, the Burnham Declaration of 1997, and the Lincoln Agreement in 1998. These initiatives created a template, pioneered on Bougainville, whereby Australia and New Zealand gather neighbouring Pacific forces from countries such as Fiji, Tonga, and Vanuatu to provide logistical and operational support for regional Pacific forces to take the lead, respecting traditional Melanesian culture (kastom) to ensure the missions are culturally sensitive and therefore effective.

A peaceful resolution to the Bougainville question is important for Australia. It was a protagonist during the colonial period and subsequent conflict, and it has invested heavily in a largely successful peace process since. Moreover, at a time of growing geopolitical contest in its immediate region, Australia and its regional partners will be keen to demonstrate they remain reliable security guarantors in the Pacific region.

Australia must be ready for a variety of possible situations, including: a refusal by the PNG parliament to ratify a vote for independence, which could lead to unrest; a rejection of the vote by PNG — or a delay on reaching settlement — which could lead to another unilateral declaration of independence by Bougainville; and finally, a substantial deterioration in the security situation, which could potentially require the deployment of another regional peacekeeping force or peace enforcement operation.

Bougainville is richly endowed with mineral resources such as copper, gold and silver, and such resources could contribute to underwriting a new nation state. However, the potential for dispute and renewed conflict over mining rights is very real and adds to the tensions between PNG and Bougainville over the referendum.

If the people of Bougainville vote for independence as expected, it is not clear whether the PNG parliament will ratify that vote according to a timeframe acceptable to Bougainvilleans, or even ratify it at all. Before Peter O’Neill’s resignation as PNG prime minister in May 2019, his government had withheld promised funds for the ABG and referendum, and insiders claimed he was reluctant to ratify any “yes” vote for independence. This added uncertainty and considerable tension to the peace process. However, Bougainvilleans are encouraged by early signals that the new Marape government supports the referendum process, with funding for the referendum released in its first week of government.[7] The appointment of veteran politician Sir Puka Temu as the Minister for Bougainville Affairs was also well received in Bougainville.

Australia is trying to balance its close relationship with PNG with supporting the ABG as it manages its current autonomy status and prepares for a referendum on independence. So far the peace process has proven successful, but there are key questions over the ABG’s capacity to conduct a rigorous referendum; Port Moresby’s readiness to honour the result if the vote is “yes”; and the role Australia should play before and after the event. With the real possibility of a new nation emerging in Australia’s immediate region for the first time since Timor-Leste, it is essential to understand what is at stake for Australia and the region and how best to manage the process and outcome.

Australia should navigate carefully its relationships with both PNG and the people of Bougainville to support the peace process and a free and fair referendum without being seen to influence the outcome. If the outcome of the referendum is an overwhelming vote for independence, Canberra must be prepared for two possibilities: either the creation of a newly independent nation in the region, or a crisis unfolding in the region if the PNG government refuses to ratify the result.

This Analysis will set out the events leading up to the referendum, including the history of the conflict and the process leading to the BPA; it will assess the likely outcome of the referendum; and finally review Canberra’s policy options both before and after the referendum.

An embattled island

Taim bifo (the time before)

The two main islands of Bougainville and Buka and a number of smaller island groups and atolls are all part of PNG’s Autonomous Region of Bougainville, formerly known as North Solomons Province (NSP). It lies to the east of mainland Papua New Guinea and close to the border of neighbouring Solomon Islands. Bougainville has a population approaching 300 000 people with 19 main language groups.

Bougainvilleans claim that their traditional trade links and affinities before European contact were mainly with those of the western and central islands of the Solomons chain rather than with the PNG mainland. There was also substantial contact with seafaring Polynesians who came to trade and settle in some of the outlying atolls.

The first recorded European contact with Bougainville was by the French explorer Admiral Louis Antoine de Bougainville in July 1768. De Bougainville named the main island after himself but the French never settled it. In the late 1800s Germany claimed northern New Guinea and its islands, including Bougainville. Settlers established large copra plantations, and the largest of them, the German Neuguinea-Kompagnie, informally assumed the role of administrator.[8]

The German administration of New Guinea, including Bougainville, came to an end in 1914 at the outbreak of the First World War when the Australian military took control of the island. As a result of lobbying by Prime Minister Billy Hughes after the war, the League of Nations assigned the former German territory of New Guinea to Australia to administer.

From 1918 to 1975 — interrupted by Japanese occupation during the Second World War[9] — Bougainville was administered by Australia, first as a mandated territory on behalf of the League of Nations, then as a “trust” territory on behalf of the United Nations following the war.

The emergence of Bougainvillean identity

Before colonisation, Bougainville and Buka (the island to its north) shared little in the sense of island nationalism or ethnicity. The arrival of European rule changed this, with grievances against the colonial regimes driving the island populations together towards the semblance of a pan-Bougainville identity. Perhaps the strongest factor in entrenching this Bougainvillean identity, however, was the establishment of the Panguna copper and gold mine near Arawa in the 1960s and early 1970s during the period of Australian colonial administration.[10] The mine was operated by Bougainville Copper Limited (BCL), an Australian subsidiary of Rio Tinto, and sought to tap large deposits of copper, gold and silver in the Emperor mountain range.

While the arrival of the mine brought infrastructure and helped to modernise Bougainville, perceived inequities in the distribution of compensation and revenue alienated local communities. From the start, the mine had provoked protests, with local women pulling out survey markers and standing in front of bulldozers.[11]

The shift to autonomy

The grievances created by the establishment of the Panguna mine stoked emerging ethno-nationalist sentiment and generated a groundswell of opposition to both the mine and the Australian colonial administration. Throughout this period, kastom and cult movements such as the Hahalis Welfare Society and Napidokoe Navitu were agitating for rights, self-determination, and secession. James Tanis, who became the second president of Bougainville, articulated the sense of alienation: “We never felt we were Papua New Guineans.”[12]

The resentments spread beyond the kastom movements to the general community, and led to a series of confrontations with the administration in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[13] The protests culminated when local leaders, intent on pre-empting PNG rule before it gained full independence on 16 September 1975, made Bougainville’s first unilateral declaration of independence on 1 September 1975.

The declaration was ignored by both the outgoing Australian administration and the incoming PNG one, but signalled Bougainville’s desire for self-determination. Instead, a deal was done between founding fathers Michael Somare and Fr John Momis to allow Bougainville a type of autonomy in the form of a ‘provincial government’ as an inducement to stay part of the PNG nation.

Seeds of war

By the 1980s, Bougainville was considered among the most advanced and wealthiest provinces in PNG. The Arawa area in which the Panguna mine was located had a well-equipped hospital, schools and roads, and had the second-highest per capita income of all PNG provinces. It produced 14 per cent of PNG’s national income and half of its exports. Life expectancy, infant mortality, and educational indicators were all substantially superior to the PNG average.[14]

The mine’s management spent significant amounts of money on social services and infrastructure on the island. Bougainvilleans employed at the mine learned trade skills and were offered scholarships for further education. Many Bougainvilleans used the skills learnt at the Panguna mine and other businesses in Arawa to find employment elsewhere in PNG, Australia and beyond. According to academic Donald Denoon:

“BCL (Bougainville Copper Limited) tried to become good corporate citizens. Services were devised to help small businesses and to provide agricultural extension. BCL canteens were good markets for growers and local contractors moved into transport, security and building.”[15]

Despite this material progress, discontentment on Bougainville persisted. While around a third of the mine’s employees were Bougainvilleans, Arawa locals were insufficiently skilled for most of the jobs.[16] Locals were aggrieved at PNG mainlanders (‘redskins’) taking mine jobs away from the local labour pool, and involving themselves in local politics. Prostitution, gambling and squatting on kastom land all increased over the time of the mine’s operation. The Panguna mine was a major part of PNG’s national economy,[17] but Bougainvilleans were resentful at underwriting it, and when combined with the social tensions from the growing influx of foreigners and redskins, this hardened Bougainville nationalism and sowed the seeds of future conflict.

There were also unresolved issues with PNG’s oversight of the mine, including its failure to conduct regular reviews of the mine lease every seven years, as stipulated in the original mining agreement. Bougainvilleans felt the government had failed in its duty to protect their interests when dealing with the mine and its foreign owners. The mine was seen as very profitable for the company and for the PNG state, but less so for the provincial government and the Bougainvillean people.[18] BCL’s own records show that from the mine’s profits between 1972 and 1989, approximately 1 billion kina was given to the PNG Government in tax and royalties (roughly 20 per cent of total production value), while landowners and the provincial government received 5 per cent each of the total royalties — around 110 million kina.[19] Landowners and other Bougainvilleans regarded these as insufficient compensation.

As the mine operator, BCL was caught between intergovernmental rivalry — national versus provincial — and unrealistic local expectations.[20] There were other rumours as well: that BCL was planning more mines on the island, adding to locals’ fears of further disenfranchisement and dislocation.[21] A younger, second generation of landowners formed the New Panguna Landowners Association (NPLA),[22] led by Perpetua Serero and a mineworker called Francis Ona, who demanded a more equitable distribution of compensation from older landowners and the mine. When that failed, the NPLA demanded 10 billion kina in compensation from BCL as well as other concessions. BCL declined. It was at this time that the fledgling Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA), led by Ona, emerged.[23]

War and peace: 1988–2018

The war began in late 1988 when Ona led a small cell of armed followers in disruptive operations against the Panguna mine and the PNG state. It lasted for ten years.

Stolen dynamite was used to blow up mine facilities, including power pylons.[24] A number of mine workers, including an Australian, were shot. The BRA escalated its attacks, and PNG police and the PNG Defence Force (PNGDF) were brought in to restore order, but their heavy-handed methods aggravated the conflict.[25] After 17 years of production, the mine was closed in May 1989 and a state of emergency declared as PNG sent riot police and the PNGDF to pursue the rebel BRA.

The brutality of PNG forces turned many Bougainvilleans towards the BRA. However, BRA killings and intra-island ethnic tensions, in turn, created a Bougainville Resistance Force (BRF) — locals who largely collaborated with the PNGDF, often to seek payback against the BRA, even if many of them ultimately wanted independence too. The BRF fought alongside the PNGDF for fear that a future independent Bougainville would be dominated by Nasiois (Central Bougainvilleans, who made up the bulk of the BRA’s leadership).

This led to a protracted conflict that claimed an estimated 10 000–15 000 lives, mostly through preventable disease and lack of medicine.[26] A naval blockade of Bougainville during the war prevented much-needed medicine getting in and the wounded and sick getting out through the sympathetic Solomon Islands. The number of actual combat deaths between BRA, BRF and PNGDF forces is unclear, but perhaps accounted for between 1000 and 2000 lives.[27]

Australia was placed in a difficult position. Its policy at the time, as set out by then Prime Minister Bob Hawke, was that “Bougainville must remain an integral part” of PNG.[28] While it was naturally inclined to assist its long-time partner as PNG’s security forces attempted to wrest back control, there were loyalties to the Bougainvilleans too, and Canberra sought to facilitate truce talks between the parties to the conflict.[29] Through the established Defence Cooperation Program, however, Australia continued to train and equip the PNGDF. It had also donated four Iroquois helicopters for transport and medevac purposes in response to an earlier request from PNG predating the crisis, flown by Australian and New Zealand civilian pilots.[30] There is evidence that the PNGDF used the helicopters as gunships to fire on villages and in other incidents,[31] contributing significantly to Bougainvilleans’ suspicions and mistrust of Australia.

In 1997 the Sandline mercenary crisis erupted and marked a final attempt by the PNG Government, led by Sir Julius Chan, to secure Bougainville by force. It hinged on a secret deal to bring in mercenaries from Africa, led by British army veteran Tim Spicer, to take Panguna first and then the island. However, the mission was aborted when the PNGDF Commander, Brigadier-General Jerry Singirok, opposed the operation. The PNGDF rounded up the mercenaries and arrested Tim Spicer. After a tense standoff at parliament house between the police and army, as well as large public demonstrations, Sir Julius Chan resigned as prime minister and the Sandline operation was called off.[32]

The crisis propelled the parties to seek a truce in a process that began in late 1997 and culminated in the Burnham Agreement shortly thereafter. New Zealand led the negotiations, supported by Australia, which then established a Peace Monitoring Group of 300 military and civilian peacekeepers on Bougainville. In April 1998 a formal ceasefire was concluded. The final stage of the peace process was the completion of the Bougainville Peace Agreement, which was signed on 30 August 2001 in Arawa by all major parties to the conflict, including PNG’s then Prime Minister Sir Mekere Morauta, the Governor of Bougainville’s Interim Provincial Government, John Momis, and the BRA Chief of Defence, Ishmael Toroama.[33]

Peace and the referendum deal

The peace agreement was based on PNG’s commitment to constitutional amendments guaranteeing Bougainville the right to hold a referendum on independence, the formation of an Autonomous Bougainville Government, and a plan for weapons disposal. PNG signed the BPA on the basis that any referendum result would need to be ratified by the PNG parliament following consultation between both governments, giving PNG a veto power.

The BPA was a significant outcome and the ongoing peace process is rightly lauded as a major success and model for conflict resolution worldwide. The war ended, the peace has held since then and a resolution is within reach.

However, for both parties to the agreement — Bougainville and PNG — the looming referendum is causing strains. On Bougainville, there are still tensions on the ground stoked by those who remain outside the BPA process. These are primarily the two factions known as ‘Me’ekamui Panguna’ and ‘Me’ekamui U-Vistract’. The former control the area around the Panguna mine and have agreed to ‘contain’ their weapons (a process formally outlined in the BPA to securely lock away weapons for later disposal).[34] They have an agreement in place with the ABG and an organised group of former combatants (known as the ‘Core Group’) not to disrupt the peace process, and will actively participate in the upcoming referendum. They are unlikely to be a threat to the peace process but are regarded as something of an ‘insurance policy’ for the BRA and pro-independence groups in the unlikely event PNG attempts another military action against Bougainville.

The other group, Me’ekamui U-Vistract, is led by Noah Musingku, who is wanted for financial fraud over his promotion of pyramid money schemes.[35] Musingku remains a wild card. He is the only factional leader to be holding weapons and telling his followers not to vote in the upcoming referendum, claiming “we are already independent”.[36] While the group presents a risk to the peace process and upcoming referendum, they have been generally quiet and sequestered in South Bougainville.

On the PNG side, successive governments, particularly the O’Neill government, have wrestled with the referendum process. For some time, the O’Neill government withheld funding from the ABG and the referendum process as promised under the terms of the BPA. Bougainvilleans are more hopeful now, however, given the funding provided by the new Marape government and its stated commitment to honour the terms and spirit of the BPA. To allow more time to register voters and properly fund the referendum, the date of the vote was pushed back from June to October and then November. Doubts about the accuracy of the common roll — as reported following the 2017 PNG elections[37] — have eased somewhat, with a new ward system and voter registration in place.

Outside the immediate region, powers such as China and Indonesia are positioning themselves for the potential outcomes of the referendum. A Chinese delegation is rumoured to have offered substantial funds in late 2018 to help finance a transition to Bougainville independence, along with offers to invest in mining, tourism and agriculture, with a figure of US$1 billion cited.[38] A new port in the Bana district of East Bougainville was also reportedly discussed.[39]

Indonesia, on the other hand, is likely to be concerned at the prospect of a successful Bougainville referendum lest it create a regional precedent for West Papua, where significant elements of the population are also agitating for a referendum and eventual independence.[40] Jakarta was “not at all happy” that West Papua had been included on the agenda for the 2019 Pacific Islands Forum in Tuvalu.[41]

Amid these uncertainties, tensions and potential flashpoints, Australia has a responsibility — and an interest — to see that peace is maintained, a credible referendum held, and a negotiated outcome achieved to ensure a lasting peace so that Bougainville does not become a source of regional instability again.

The referendum

The ABG and relations with PNG

Relations between Bougainville leaders and their PNG counterparts have always blown hot and cold. ABG President John Momis was once a supporter of Bougainville autonomy but now backs independence.[42] Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare would like to see Bougainville remain part of the PNG family but acknowledges the troubled history between the two.[43]

Some previous PNG prime ministers such as Sir Julius Chan, Paias Wingti, and Sir Rabbie Namaliu tried to retake Bougainville by force. Others, such as Bill Skate, Sir Mekere Morauta and Peter O’Neill, have allowed the peace process to unfold. There were disputes over the lack of promised budget funding by the O’Neill government. O’Neill gave mixed signals as to his policy on Bougainville during his term, with insiders privately saying he had no intention of ratifying the vote and was seeking to delay the referendum and final decision for as long as possible. Momis had become increasingly strident in his criticism of the parliament in Waigani before the recent change of government, and claimed that PNG was trying to “sabotage” the referendum.[44] However, various concessions in the last year of that government — on the referendum question, enrolment of non-resident Bougainvilleans and allocation of funds to the BRC — suggested that a referendum would have proceeded, although not necessarily been ratified, under the O’Neill government.

Anecdotal evidence and media commentary in the lead up to the referendum suggest that while the PNG government would strongly prefer Bougainville to remain part of PNG,[45] sentiments across parliament are not uniform. A number of influential politicians have declared that PNG should “give political independence to Bougainville”, alongside calls for West Papuan independence.[46] Some PNGDF sources suggest PNG would be better off ‘cutting Bougainville loose’. This would allow PNG to focus defences on its Indonesian border and the potential for unrest there, rather than its eastern border. The PNGDF has no greater resources today than it had 20 or 30 years ago and is ill prepared for military action in Bougainville. Some Papua New Guineans cite concerns that a vote for independence may contribute to a potential ‘unravelling’ of PNG and spark a domino effect in other provinces. New Ireland and East New Britain, for example, have long aspired to greater autonomy from PNG.[47]

The new PNG government is making progress on the referendum issue. Sir Puka Temu, PNG’s new Minister for Bougainville Affairs, is married to a Bougainvillean and is well regarded there. In his short tenure as minister he has already made significant efforts to engage with Bougainvilleans.[48] Prime Minister Marape has spoken positively about the referendum process and in September 2019 addressed the Bougainville House of Representatives, where he announced a ten-year one billion kina (A$427 million) infrastructure plan for Bougainville to foster economic independence.[49] PNG’s preference on the result of the referendum is clear, however. In parliament in late August, Marape expressed his administration’s preference for the “greater autonomy arrangement” rather than independence but added “[the] government will not deviate from the spirit of the 2001 Peace Agreement”.[50]

Is Bougainville ready?

While it has limited funds and human resources, the ABG is working to prepare for the referendum in November. The cost of the referendum is being met by a combination of funding including from PNG and Australia and from external partners such as the UN Peacebuilding Fund.[51] Former Irish Taoiseach (prime minister) Bertie Ahern was appointed chair of the referendum commission in late 2018 and is working with PNG and Bougainville to ensure a legitimate and successful referendum.[52]

The referendum presents significant challenges on issues such as voter registration, public awareness, and security. Updating the common roll is one of the most important tasks, but the Referendum Commissioner claims to be confident of being ready in time.[53] The ABG has a process in place in which its 33 constituencies take steps to declare themselves ‘referendum ready’, which all have now done.[54]

Bougainvilleans want the referendum to happen in a free and fair manner, and some have expressed frustrations with the lack of information on the process, including registration of voters. However, a six-week delay to the referendum from October to November has allowed more time for preparation,[55] and the new Marape government in Port Moresby appears more committed to the process than the previous administration.

Concerns about lack of information are real.[56] There is currently no PNG or Australian news radio service available in Bougainville. PNG’s NBC service only reaches Buka and parts of North Bougainville.[57] Although the United Nations promised to assist with communications and awareness, there is little evidence of this apart from a television screen outside the main market in Arawa and a recent “roadshow tour” by UN, PNG Government and ABG officials. There is a referendum website which provides basic information,[58] and while the ABG’s own website is a good source of general information and ABG-related news,[59] there is very little news reporting and analysis within Bougainville. News arrives via flown-in copies of PNG’s Post-Courier and National newspapers to Buka, limited cable TV at some guest houses in Arawa, and reports from Buka-based New Dawn FM news.[60] In this information-poor environment, many Bougainvilleans (particularly in urban areas) rely on social media including Facebook pages such as Voice-Bougainville and Bougainville Forum, but even this is limited, with patchy internet access across the province.

The ABC’s cessation of shortwave broadcasting to the region means it cannot play the role it did in the vote for East Timor’s independence.[61] In Bougainville and elsewhere, the loss of ABC reporting and reach in the Pacific has opened up a void of reliable regional information and undermined Australia’s regional influence.

The issue of weapons disposal is another potential obstacle. Under the BPA, all armed groups in Bougainville were required to surrender their weapons for containment and then destruction under UN supervision.[62] Significant numbers of weapons have already been destroyed in accordance with this process.[63] However, a breakaway group — Noah Musingku’s Me’ekamui U-Vistract faction — has so far refused to participate in the process and reportedly retains some weapons.[64] This has caused concern about the potential for armed groups to disrupt the process, as well as fears that the failure to complete the weapons disposal process could be used by PNG as an excuse to delay or not recognise the outcome of the referendum.[65] However, the Me’ekamui U-Vistract faction is small, and the disruptive threat it poses to the conduct of the referendum is unlikely to be significant.[66]

After the referendum

A vote for independence, even if it is decisive as expected, would not be conclusive. For independence to proceed under the BPA, the PNG parliament must endorse the outcome. Under former Prime Minister Peter O’Neill, it appeared the PNG Government would resist such an outcome,[67] and the new Marape government has expressed a preference for keeping Bougainville within PNG but granting it further autonomy.[68]

Economic viability

A critical question is whether Bougainville has the necessary resources — human and material — to become an independent, economically viable nation. Among the pressing challenges are those of educating and mobilising a ‘lost generation’ of younger people disenfranchised by the war while forging national unity and bringing integrity to Bougainville’s political system.

Economically, Bougainville’s prospects for self-reliance are very unclear. According to the formal definition of self-reliance in the BPA, by 2016 Bougainville had reached less than 6 per cent of the necessary internally generated revenue. Even taking into account all sources of revenue (not just those nominated in the BPA), the most recent estimate is 56 per cent — still a significant shortfall.[69] The challenges of achieving fiscal self-reliance should not be underestimated, as Sir Puka Temu has pointed out, and would require substantial support from PNG and stakeholders — including Australia — in the region.[70]

Bougainville is well endowed with mineral resources, but these — and specifically the Panguna mine — have been the cause of enormous conflict in the past, and the prospects of reinstating a large-scale mining industry are uncertain.[71] Reopening Panguna would involve revisiting the same issues that triggered the conflict in 1988.[72] While pragmatists advocate its reopening now, to position the economy better for independence, others insist that mining issues should be left alone until after Bougainville becomes independent.[73] Under President Momis, the ABG has given mixed signals as to its position on mining. After a failed bid by BCL to restart exploration on Bougainville, Momis initially supported a moratorium on mining at Panguna to prevent reigniting old conflicts.[74] The moratorium was put in place in early 2018,[75] but the ABG now appears to favour mining across the island as a means to generate income and underwrite independence.[76] In an urgent bid in January 2019 to raise funds for the referendum, the ABG proposed controversial new legislation abolishing landowners’ rights granted in the 2015 Mining Act. At the same time, it allocated “near monopoly” rights to one company — the little-known Australian Caballus Mining — over all mining and exploration on Bougainville.[77] This legislation has now been rejected by ABG’s legislative committee, but illustrates the escalating competition for mining rights on Bougainville.

Feasibility studies to reopen the Panguna mine are underway, but even if the moratorium were lifted now, the earliest the mine could reopen would be 2025, given the substantial work and investment needed to make it operational.[78] An estimated US$4–6 billion in construction costs would be required, and such an investment would involve substantial sovereign risk given the uncertainty of Bougainville’s future. However, the buried wealth — estimated at 5.3 million metric tons of copper and 19.3 million ounces of gold, and worth about US$58 billion at today’s prices — remains attractive.[79]

Apart from mining, Bougainville has other potential sources of income, including fisheries and cocoa production. One estimate has 30 per cent of PNG’s fish catch coming from Bougainville waters, worth between 30 and 100 million kina per year.[80] Bougainville has also been an exporter of high-value marine products such as Beche-de-Mer (dried sea cucumber), an industry that has been recently revived.[81] Bougainville’s large cocoa plantations are increasingly being sourced by chocolate makers at home and abroad. Small-scale gold-mining has also been an important source of income.[82] These are resources that could make some contribution to economic self-reliance over time.

However, given Bougainville’s small size, fractious internal relations and the difficult history of the exploitation of its most valuable resource, self-reliance would, at best, be years away.

Therefore, in the event of an independence vote and a negotiated settlement on independence reached with PNG, Bougainville would require substantial assistance from both PNG and external partners such as Australia in making the transition to independence and fiscal self-reliance. Yet to date, there is scant evidence of planning for such a transition, if that is the outcome of the referendum and negotiations.

Regional perspectives

Indonesia is watching the referendum process closely. With tensions erupting in West Papua,[83] Jakarta will be concerned about the potential demonstration effect of an independence vote on the people of West Papua. Meanwhile, China’s already active diplomacy and investment in the region could extend to assisting an independent Bougainville, enlarging China’s presence in the Pacific. The Pacific Islands have long been the subject of intense competition between China and Taiwan for diplomatic recognition, and an independent Bougainville would likely be courted by both.

The Solomon Islands has its own history with Bougainville and needs to be included in any analysis. Breakaway movements have surfaced periodically in Solomons’ Western Province, including at the time of the Solomons’ independence in 1978.[84] During the Bougainville conflict, the western Solomons provided refuge for many displaced Bougainvilleans, and in the early 1990s PNG accused the Solomons Government of allowing the BRA to operate from Solomons territory.[85]

In June 2019, however, Honiara appears less likely to welcome Bougainville’s independence. Solomons Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare suggested in early June that the referendum be deferred until Bougainville had resolved its internal differences.[86]

Australia’s position

Australia is a valuable aid partner to Bougainville, providing around 12 per cent (A$50 million per annum) of Bougainville’s bilateral aid program, the highest of any donor.[87] It has positioned itself as the partner of choice for Pacific nations, particularly after the “step up” commenced in 2017. Given its complicated history on Bougainville together with its investment in the peace process and since, Australia is in a difficult situation.

Before 2000, Australian policy was based on the principle that Bougainville was part of PNG. This shifted following a turning point in peace negotiations between PNG and Bougainvillean leaders in 2000, when Foreign Minister Alexander Downer announced that “Australia will accept any settlement negotiated by the parties”.[88] This position has not been altered since.[89]

Most Bougainvilleans believe that Australia opposes independence, because Canberra has made no overt indication of its views. When Foreign Minister Marise Payne briefly visited Bougainville in June 2019 with PNG’s newly appointed Minister for Bougainville Affairs, she said Australia was “not [focused on] forming a view one way or another about the outcome of a referendum in another country, but importantly, supporting [the referendum] where we can, to ensure a credible and a peaceful and inclusive process”.[90] In August, the Minister stated, “The outcome is entirely a matter for Bougainvilleans and PNG ... We will do anything we can to [assist] in ensuring that [the] referendum takes place in [an] appropriate fashion.”[91] Despite these expressions of neutrality, it is likely that Australia regards the status quo as preferable:[92] that is, that Bougainville should remain part of PNG, avoiding the potential for another small, and potentially unstable and aid dependent new nation emerging in Australia’s immediate region.

Dealing with the consequences

There are three possible outcomes of the referendum vote: a vote against independence, a sharp division, or a clear result in favour of independence. All indications are that the probable outcome is a decisive vote for independence.

If the result is a sharp division on independence within the Bougainville population, PNG will likely press for the status quo (keeping Bougainville within PNG under the ‘greater autonomy’ option) and attempt to contain the consequences of the referendum vote.

If the result is strongly in favour of independence, it will be harder for PNG to press for the autonomy option. Having honoured the BPA process, PNG will face the unenviable choice of asserting its wishes or working with Bougainville on a transition to independence.

Australia will be unable to avoid dealing with the consequences of that result. Critical to its interests is averting another security crisis in the region for which it is the primary security guarantor and principal development partner.[93]

Australia should therefore do whatever it can to encourage and support a credible process of consultation between PNG and the ABG in pursuing a post-referendum settlement under the BPA. Throughout the process it should reiterate its neutrality as to whether Bougainville ultimately proceeds to independence or not. If PNG, Indonesia or Australia were to attempt to deny or persuade against Bougainville independence after the poll, there is a strong possibility the Bougainville administration would issue another unilateral declaration of independence that some countries in the Pacific — and China — might recognise. In that scenario, the potential for another serious security crisis in the region is real.

Under either possible result of the referendum, Bougainville will at the very least move to a ‘greater autonomy’ status within PNG, and will need to develop its economic self-reliance and institutional capacity. In the context of Australia’s Pacific “step up”, the history of its relations with Bougainville and China’s increasing presence in the region, Australia will be keen to preserve its role as trusted partner to both Bougainville and PNG. Australia should step up its aid and trade program to stimulate the local economy through non-mining businesses and, post-referendum, establishing vocational centres to help recruit and train up a civil service, if invited. It should work with the ABG and PNG to improve Bougainville’s fiscal self-reliance: helping to expand employment in Bougainville, and improve conditions and policies to support a stronger agricultural sector, high-value marine exports and onshore tuna processing.

If the final outcome of the referendum and BPA process is Bougainville’s independence, its development needs as a fledgling nation will be acute. Given the lure of its mineral wealth and the evolving strategic significance of the region, there are likely to be potential development partners other than Australia.[94] As both PNG’s and Bougainville’s principal aid partner, Australia should take the lead in providing support.

An Australian leader, at prime minister or governor-general level, should visit Bougainville — with PNG officials — after the referendum. An Australian leader should take part in a reconciliation ceremony in which Australia’s history in Bougainville is acknowledged, including its involvement in the Bougainville conflict. This would go a long way to restoring the image of Australia in local eyes and fit with the Morrison government’s Pacific ‘family’ approach to relations.

A genuine gesture of reconciliation — known as sori bisnis, or to break bows and arrows — would help position Australia as a trusted partner, overturning the prevailing perception that Australia continues to work with PNG to deny Bougainville independence. This may help nudge PNG towards a peaceful resolution of this long-running discord by allowing Australia to shoulder some of the responsibility for the past. It also sends a subtle signal to Jakarta and Beijing that Australia and its Pacific allies will continue to assume primary responsibility for peace and security in the region.

Australia’s foreign minister should clearly reiterate Australia’s position now — that it supports the referendum and will respect any outcome of the BPA process — and take a leading role to work with all parties to ensure a peaceful transition to either greater autonomy or full independence.

Conclusion

Despite facing numerous obstacles, it is expected that the key elements will be in place for a legitimate referendum to be conducted in November 2019.

Australia, New Zealand, and the United Nations have stepped in to assist with finance and organisational assistance in light of PNG’s previous unwillingness to do so. The new Marape government’s quick release of the final budgeted funding for the referendum is encouraging.[95] Election monitors from a number of Pacific nations as well as representatives from regional organisations such as the Melanesian Spearhead Group and Pacific Islands Forum will be on the ground. The electoral roll is still being finalised, but is expected to be satisfactory by the time of the vote. There is a slight possibility of disruption from Noah Musingku’s faction, but his support base is small and unlikely to create any real problems for the vote.

In the event of a strong vote for independence in the referendum, the momentum towards independence will be difficult to restrain.

A major policy question is therefore what a transition to independence might look like. It could be rapid, or managed over several years, such as the UN-assisted, three-year transition of Timor-Leste to full sovereignty. PNG and the ABG would need to assess whether UN assistance for the process should be requested, and what an acceptable time frame would be, including for hardliners seeking a short transition.

Australia can offer a range of assistance as long as it is mindful of the historical baggage it carries from its support for PNG during the conflict. Despite this, there remains much general goodwill towards Australia, particularly from the role it played with New Zealand in supporting the peace process which is now widely regarded as a global model for conflict resolution.

The larger question is whether Bougainville itself is ready for independence. The short answer is no, but most Bougainvilleans see no alternative to independence, despite the obstacles.

Abbreviations

- ABC

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- ABG

- Autonomous Bougainville Government

- BCL

- Bougainville Copper Limited

- BPA

- Bougainville Peace Agreement

- BRA

- Bougainville Revolutionary Army

- BRC

- Bougainville Referendum Commission

- BRF

- Bougainville Resistance Force

- JSB

- Joint Supervisory Body

- MSG

- Melanesian Spearhead Group

- NPLA

- New Panguna Landowners Association

- NSP

- North Solomons Province

- PIF

- Pacific Islands Forum

- PLA

- Panguna Landowners Association

- PMG

- Peace Monitoring Group

- PNG

- Papua New Guinea

- PNGDF

- Papua New Guinea Defence Force

- RAMSI

- Regional Assistance Mission Solomon Islands

- SPRPKF

- South Pacific Regional Peace Keeping Force

- TMG

- Truce Monitoring Group

- UDI

- Unilateral Declaration of Independence

Notes

[1] “Record of Meeting: Special Meeting of the Joint Supervisory Body”, Port Moresby, 11–12 October 2018, http://bougainville-referendum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/JSB-Resolutions-12-October-2018.pdf.

[2] Bougainville Referendum Commission, http://bougainville-referendum.org/; Annmaree O’Keeffe, “Bougainville’s Panguna – ‘A Challenging Opportunity’”, The Interpreter, 21 December 2018, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/bougainvilles-panguna-challenging-opportunity.

[3] See also, for example, Shane McLeod, “James Marape Gets Clear Air to Establish New PNG Administration”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 June 2019, www.smh.com.au/world/asia/james-marape-gets-clear-air-to-establish-new-png-administration-20190531-p51tbm.html; Stefan Armbruster, “Australia Could Soon Have a New Pacific Nation Next Door”, SBS News, 16 July 2019, www.sbs.com.au/news/australia-could-soon-have-a-new-pacific-nation-next-door.

[4] See Bougainville Peace Agreement, signed at Arawa 30 August 2001, 58, http://www.abg.gov.pg/uploads/documents/BOUGAINVILLE_PEACE_AGREEMENT_2001.pdf; see also “Bougainville Govt to Push for All to Vote ‘Independence’”, RNZ, 16 October 2018, www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/368787/bougainville-govt-to-push-for-all-to-vote-independence?fbclid=IwAR0IWVwa-SnYOY_ya-iHjuM58Gc8-aoAW17JBOQP1xco2ordAWMTQWEIGxE.

[5] Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Bougainville: The Peace Process and Beyond, Report submitted to Parliament 27 September 1999, “Chapter 1: Introduction”, 6, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Completed_Inquiries/jfadt/bougainville/BVrepindx.

[6] For a history of peace missions in Bougainville, see Edward Wolfers, “International Peace Missions in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, 1990–2005: Host State Perspectives”, Regional Forum on Reinventing Government Exchange and Transfer of Innovations for Transparent Governance and State Capacity, Nadi, Fiji, 20–22 February 2006, unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan022601.pdf.

[7] The Marape government released the final budgeted funding (10 million kina, A$4.3 million) to the BRC in June 2019: “Referendum Funds Released, Maru Says”, The National, 7 June 2019, https://www.thenational.com.pg/referendum-funds-released-maru-says/.

[8] John Braithwaite, Hilary Charlesworth, Peter Reddy and Leah Dunn, Reconciliation and Architectures of Commitment: Sequencing Peace in Bougainville (Canberra: ANU E Press, 2010), 10, https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/series/peacebuilding-compared/reconciliation-and-architectures-commitment.

[9] More than 40 000 Japanese soldiers perished on Bougainville, including from sickness and disease. Australia lost 516 men (almost as many as in the Vietnam War) with 1572 wounded: Karl James, “More than Mopping Up: Bougainville”, in Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific, Peter Dean ed (Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 248.

[10] Anthony Regan, “The Bougainville Referendum Arrangements: Origins, Shaping and Implementation — Part One: Origins and Shaping”, ANU Bell School Department of Public Affairs, Discussion Paper 2018/4, 2, https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/147139/1/DPA%20DP2018_4%20Regan%20pt%201%20final.pdf.

[11] One of the defining aspects of Bougainville is its matrilineal society in which women are custodians of the land. As John Braithwaite et al noted: “BCL got off to a bad start … There was a failure to grasp the spiritual, cultural and social dimensions of land; it was not simply the commodity that BCL negotiators treated it as being … ‘In matrilineal society, when women wail and confront something, it’s a big signal.’” Braithwaite et al, Reconciliation and Architectures of Commitment: Sequencing Peace in Bougainville, 15.

[12] James Tanis, “Nagovisi Villages as a Window on Bougainville in 1988”, in Anthony Regan and Helga Griffin eds, Bougainville before the Conflict (Canberra: ANU Press, 2015), 468, https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n1653/pdf/book.pdf.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Satish Chand, “Financing for Fiscal Autonomy: Fiscal Self-Reliance in Bougainville”, PNG National Research Institute Research Report No 3, August 2018, 3, http://www.abg.gov.pg/uploads/documents/Financing_for_fiscal_autonomy-_Fiscal_Self-reliance_in_Bougainville_.pdf.

[15] Donald Denoon, Getting under the Skin: The Bougainville Copper Agreement and the Creation of the Panguna Mine (Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press, 2000), 168.

[16] Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Bougainville: The Peace Process and Beyond, “Chapter 2: History of the Bougainville Conflict”, 18–19.

[17] The mine was providing 45 per cent of Papua New Guinea’s export income, 17 per cent of internally generated government revenue and 12 per cent of GDP: Braithwaite et al, Reconciliation and Architectures of Commitment: Sequencing Peace in Bougainville, 20.

[18] Based on views given to the author by Bougainville leaders, including Joe Kabui and John Momis.

[19] Bougainville Copper Limited, “History of Panguna Mine”, http://www.bcl.com.pg/history-panguna-mine/; Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Bougainville: The Peace Process and Beyond, “Chapter 2: History of the Bougainville Conflict”, 17–19.

[20] Douglas Oliver, Black Islanders: A Personal Perspective of Bougainville, 1937–1991 (Melbourne: Hyland House, 1991), 154–155.

[21] Francis Ona, interviewed by the author in 1994, claimed maps taken from BCL outlined several other mining locations being planned. Maps were shown to author.

[22] The NPLA was set up in 1987 in opposition to the Panguna Landowners’ Association (PLA), which was formed in 1978.

[23] Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Bougainville: The Peace Process and Beyond, “Chapter 2: History of the Bougainville Conflict”, 21–22.

[24] Ibid, 22.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid, 13.

[27] Estimate by Braithwaite et al, Reconciliation and Architectures of Commitment: Sequencing Peace in Bougainville, 87–88. There is no official tally of the war dead. This estimate accords with the author’s interviews with PNGDF Commander Jerry Singirok (correspondence on 12 June 2019 contending that around 300 PNGDF were killed in action) and BRA Commander Sam Kauona (interview in 1998 contending that “at least 1000 BRAs and BRFs were killed”).

[28] Ron May, “The Situation on Bougainville: Implications for Papua New Guinea, Australia and the Region”, Parliamentary Research Service Current Issues Brief No 9 1996–97 (8 October 1996), 15, https://www.aph.gov.au/sitecore/content/Home/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Publications_Archive/CIB/CIB9697/97cib9#BACKGROUND.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Braithwaite et al, Reconciliation and Architectures of Commitment: Sequencing Peace in Bougainville, 30.

[31] Ibid; Mary-Louise O’Callaghan, “Australia to Give PNG Fifth Iroquois Chopper”, The Age, 28 August 1992, 3; Amanda Meade, “Helicopters Under Fire”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 June 1992, 2; Mary-Louise O’Callaghan, Enemies Within — Papua New Guinea, Australia, and the Sandline Crisis: The Inside Story (Milsons Point, NSW: Doubleday, 1999), 16. See also Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Bougainville: The Peace Process and Beyond, “Chapter 2: History of the Bougainville Conflict”, 23; May, “The Situation on Bougainville: Implications for Papua New Guinea, Australia and the Region”, 16.

[32] Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Bougainville: The Peace Process and Beyond, “Chapter 2: History of the Bougainville Conflict”, 34–36; Peter Jennings and Karl Claxton, “A Stitch in Time: Preserving Peace on Bougainville”, ASPI Special Report, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, November 2013, 3, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/special-report-stitch-time-preserving-peace-bougainville.

[33] Women were instrumental in the peace process, with leading figures such as Josephine Kauona, founding president of Bougainville Women for Peace and Freedom, and Sr Ruby Mirinka, former principal of Arawa Nursing School, representing Bougainville women at the negotiations. Sr Ruby Mirinka also read the Women’s Statement at the signing of the BPA in April 2001. See Josephine Tankunani Sirivi and Marilyn Taleo Havini eds, … As Mothers of the Land: The Birth of the Bougainville Women for Peace and Freedom (Canberra: Pandanus Books, 2004), 181, 184.

[34] The BPA details a three-stage process for weapons disposal with weapons first surrendered and placed in secure containers, and then decisions made on their disposal. See “Bougainville Peace Agreement”, Arawa, 30 August 2001, 64–65, http://www.abg.gov.pg/uploads/documents/BOUGAINVILLE_PEACE_AGREEMENT_2001.pdf.

[35] For more on Musingku see John Cox, “Fake Money, Bougainville Politics and International Scammers”, ANU State Society and Governance in Melanesia, In Brief 2014/7, http://bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2015-12/IB-2014-7-Cox-ONLINE_0.pdf.

[36] Quote related by lawyer Reuben Siara, during a meeting by the author with Core Group, including Siara, on 11 January 2019 in Arawa.

[37] See Nicole Haley and Kerry Zubrinich, 2017 Papua New Guinea General Elections: Election Observation Report (Canberra: ANU Department of Pacific Affairs, 2018), http://bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/news/related-documents/2019-05/png_report_hi_res.pdf.

[38] Author interview with members of the Core Group, including Sam Kaouna, Arawa, 11 January 2019.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Tasha Wibawa, “Why Nearly 2 Million People Are Demanding an Independence Vote for West Papua Province”, 30 January 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-01-30/west-papuans-fight-for-another-independence-referendum/10584336.

[41] Ben Doherty, “Indonesia Anger as West Papua Independence Raised at Pacific Forum”, The Guardian, 12 August 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/12/indonesia-angered-as-west-papua-independence-raises-its-head-at-pacific-forum.

[42] “Bougainville Govt to Push for All to Vote ‘Independence’”.

[43] “Somare Favours Bougainville to Stay with PNG”, RNZ, 13 April 2017, https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/328768/somare-favours-bougainville-to-stay-with-png.

[44] “Momis Claims Referendum Sabotaged”, PNG Post-Courier, 24 September 2018, https://postcourier.com.pg/momis-claims-referendum-sabotaged/.

[45] McLeod, “James Marape Gets Clear Air to Establish New PNG Administration”; Kylie McKenna, “The Bougainville Referendum: James Marape’s Biggest Challenge or Biggest Opportunity?”, DevPolicy Blog, 26 July 2019, https://devpolicy.org/the-bougainville-referendum-james-marapes-biggest-challenge-or-biggest-opportunity-20190726/.

[46] Including Governors Powes Parkop and Gary Juffa: “‘Don’t Be Afraid’ — Give Bougainville, West Papua Freedom, Says Parkop”, Asia Pacific Report, 1 February 2019, https://asiapacificreport.nz/2019/02/01/dont-be-afraid-give-bougainville-west-papua-freedom-says-parkop/.

[47] Annmaree O’Keeffe, “Deciding the Future for PNG’s Provinces”, The Interpreter, 19 October 2018, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/deciding-future-png-provinces; Bindi Bryce, “New Ireland Governor Sir Julius Chan Hails New Autonomy Agreement for PNG Provinces”, Pacific Beat, 20 July 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/radio-australia/programs/pacificbeat/new-island-aut/10016500.

[48] Don Wiseman, “Bougainville Referendum Prep Picks Up Pace”, RNZ, 5 July 2019, https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/393729/bougainville-referendum-prep-picks-up-pace.

[49] Johnny Blades, “PNG Govt Pledges 1 Billion Kina to Bougainville Over a Decade”, RNZ, 12 September 2019, https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/398636/png-govt-pledges-1-billion-kina-to-bougainville-over-a-decade.

[50] “Referendum Is Way Forward — PM”, PNG Post-Courier, 29 August 2019, https://postcourier.com.pg/referendum-way-forward-pm/.

[51] UN Peacebuilding Fund, “Building Trust in Papua New Guinea: Accompanying the Bougainville Peace Agreement”, 13 September 2018, https://unpeacebuildingfund.exposure.co/building-trust-in-papua-new-guinea; see also Bougainville Referendum Commission, “Record of Meeting: Meeting of the Joint Supervisory Body”, Port Moresby, 1 March 2019, http://bougainville-referendum.org/legal/.

[52] Aine McMahon, “Bertie Ahern Appointed to Peace Process Role in Papua New Guinea”, The Irish Times, 13 December 2018, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/bertie-ahern-appointed-to-peace-process-role-in-papua-new-guinea-1.3730640.

[53] Author interview with Ruby Mirinka, Bougainville Referendum Commissioner, Arawa, 12 January 2019; see also Bougainville Referendum Commission, “BRC Provides Upbeat Assessment of Referendum to Parliament”, 21 August 2019, http://bougainville-referendum.org/brc-provides-upbeat-assessment-of-referendum-to-parliament/.

[54] Peterson Tseraha, “Watawi Says Focus on Referendum Important”, PNG Post-Courier, 27 August 2019, https://postcourier.com.pg/watawi-says-focus-referendum-important/; Autonomous Bougainville Government, “Bougainville Declared as Referendum-Ready”, ABG News and Public Notices, 26 September 2019, http://www.abg.gov.pg/index.php/news/read/bougainville-declared-as-referendum-ready.

[55] Bougainville Referendum Commission, “BRC Will Use Extra Time Wisely to Produce a Better Roll”, 5 August 2019, http://bougainville-referendum.org/brc-will-use-extra-time-wisely-to-produce-a-better-roll/.

[56] See, for example, Wiseman, “Bougainville Referendum Prep Picks Up Pace”.

[57] Reaching an estimated 25–30 per cent of the population.

[58] Bougainville Referendum Commission, http://bougainville-referendum.org.

[59] Autonomous Bougainville Government, http://www.abg.gov.pg.

[60] Aloysius Laukai is the Manager at New Dawn FM: https://bougainville.typepad.com/newdawn/.

[61] Alexander Downer, Minister for Foreign Affairs, and Senator Richard Alston, Minister for Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, “Broadcasts to the Asia-Pacific Region”, Joint Media Release, 8 August 2000, https://foreignminister.gov.au/releases/2000/fa087_2000.html; Alex Oliver and Annmaree O’Keeffe, “Struggling to Be Heard: Australia’s International Broadcasters Fight for a Voice in the Region”, PD Magazine, Summer 2011, 53–57, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5be3439285ede1f05a46dafe/t/5be34f52c2241bb84fd40cbf/1541623644588/Int%27lBroadcasting.pdf.

[62] Autonomous Bougainville Government, “Weapons Disposal”, http://www.abg.gov.pg/peace-agreement/weapons-disposal.

[63] Patrick Marks, “Me’ekamui DF Joins Weapons Containment”, PNG Post-Courier, 1 November 2018, https://postcourier.com.pg/meekamui-df-join-weapons-containment/.

[64] “Weapons Disposal Issues Confronting Bougainville”, PNG Post-Courier, 6 June 2018, https://postcourier.com.pg/weapons-disposal-issues-confronting-bougainville/.

[66] Author interview with Core Group, Arawa, 11 January 2019. It appears a consensus has been formed among former militants not to pursue Musingku until after the referendum in order to preserve peace in the run-up to the referendum.

[67] “Bougainville Referendum Not Binding — PM”, RNZ, 11 March 2019, www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/384471/bougainville-referendum-not-binding-pm.

[68] “Referendum Is Way Forward — PM”.

[69] Chand, “Financing for Fiscal Autonomy: Fiscal Self-reliance in Bougainville”, 27.

[70] Ben Packham, “Fears Bougainville Independence Will Open Pacific Door for China”, The Australian, 19 June 2019, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/politics/fears-bougainville-independence-will-open-pacific-door-for-china/news-story/4f4f0d00293adfd4e9da65621ab73d8d.

[71] Jo Woodbury, “The Bougainville Independence Referendum: Assessing the Risks and Challenges Before, During and After the Referendum”, Australian Defence College, Centre for Defence and Strategic Studies, January 2015, 10–12, https://www.defence.gov.au/ADC/Publications/IndoPac/Woodbury%20paper%20(IPSD%20version).pdf.

[72] Chand, “Financing for Fiscal Autonomy: Fiscal Self-reliance in Bougainville”, 9–10.

[73] Catherine Wilson, “The New Battle for Bougainville’s Panguna Mine”, The Interpreter, 21 August 2018, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/new-battle-bougainville-s-panguna-mine.

[74] Ibid.

[75] O’Keeffe, “Bougainville’s Panguna: ‘A Challenging Opportunity’”; “Bougainville Mining Plan Meets with Outrage”, RNZ, 6 February 2019, https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/381886/bougainville-mining-plan-meets-with-outrage.

[76] “Bougainville Mining Plan Meets with Outrage”; Wilson, “The New Battle for Bougainville’s Panguna Mine”.

[77] “Top Lawyer Queries ABG’s Interpretation of Mining Act”, PNG Post-Courier, 21 June 2019, https://postcourier.com.pg/top-lawyer-queries-abgs-interpretation-mining-act/.

[78] Chand, “Financing for Fiscal Autonomy: Fiscal Self-reliance in Bougainville”, 27.

[79] Aaron Clark and Dan Murtaugh, “The Remote Island Sitting on $58 Billion of Gold and Copper”, Bloomberg, 11 February 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-11/-58-billion-pacific-mine-claim-seen-at-risk-as-referendum-nears; O’Keeffe, “Bougainville’s Panguna: ‘A Challenging Opportunity’”; “Bougainville Mining Plan Meets with Outrage”.

[80] Chand, “Financing for Fiscal Autonomy: Fiscal Self-reliance in Bougainville”, 25. ABG President John Momis, interview with author, January 2019. Momis noted that while PNG had allowed the “draw down” of mining rights to Bougainville, it had thus far refused to allow Bougainville to draw down fishing rights.

[81] Chand, “Financing for Fiscal Autonomy: Fiscal Self-reliance in Bougainville”, 25.

[82] Ibid, 26.

[83] “Six Killed after Indonesian Authorities Open Fire on Papuan Protesters”, South China Morning Post, 28 August 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3024700/six-killed-after-indonesian-authorities-open-fire-papuan.

[84] “Hon Solomon Mamaloni, Chief Minister, Prime Minister”, RNZ, 5 August 2011, https://www.rnz.co.nz/collections/u/new-flags-flying/nff-solomon/solomon-mamaloni; Ralph Premdas, Jeff Steeves and Peter Larmour, “The Western Breakaway Movement in the Solomon Islands”, Pacific Studies 7, Issue 2 (1984), 34.

[85] May, “The Situation on Bougainville: Implications for Papua New Guinea, Australia and the Region”, 12–14.

[86] “Solomon Islands PM Says Bougainville Referendum Should Be Deferred”, RNZ, 7 June 2019, https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/391449/solomon-islands-pm-says-bougainville-referendum-should-be-deferred.

[87] A list of the substantial aid projects Australia funds can be found at Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Australian Assistance to Bougainville”, https://dfat.gov.au/geo/papua-new-guinea/development-assistance/Pages/australian-assistance-to-bougainville.aspx.

[88] Alexander Downer, “Australia Welcomes Progress in Bougainville Peace Process”, Media Release, 24 March 2000, https://foreignminister.gov.au/releases/2000/fa020_2000.html.

[89] James Batley, “Bougainville: Hard Choices Looming for Australia? (Part I)”, The Strategist, 4 August 2015, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/bougainville-hard-choices-looming-for-australia-part-i/.

[90] Geoff Hiscock, “Mining Hopes for Independence”, Papua New Guinea Mine Watch, 1 July 2019, https://ramumine.wordpress.com/2019/07/02/mining-hopes-for-independence/; Marise Payne, “Australia Will Help Overcome Obstacles to Making MH-17 Attackers Face Court: FM”, ABC AM, 20 June 2019, 5:35 minutes in, https://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/am/fm-marise-payne-visits-bougainville-ahead-of-independence-vote/11226886.

[91] “Outcome of B’ville Vote Matter for PNG: Payne”, The National, 28 August 2019, https://www.thenational.com.pg/outcome-of-bville-vote-matter-for-png-payne/.

[92] James Batley, “Bougainville: Hard Choices Looming for Australia? (Part II)”, The Strategist, 5 August 2019, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/bougainville-hard-choices-looming-for-australia-part-ii/.

[93] See Jenny Hayward-Jones, Australia’s Costly Investment in Solomon Islands: The Lessons of RAMSI, Lowy Institute Analysis (Sydney: Lowy Institute, 2014), https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/australias-costly-investment-solomon-islands-lessons-ramsi.

[94] Packham, “Fears Bougainville Independence Will Open Pacific Door for China”.

[95] “Referendum Funds Released, Maru Says”, The National, 7 June 2019, https://www.thenational.com.pg/referendum-funds-released-maru-says/.