Labour migration as complementary pathways for refugees in the Asia-Pacific

This working paper examines whether legal labour migration schemes can be opened to humanitarian migrants who may otherwise become targets for migrant smugglers.

Abstract

This working paper looks at current legal labour migration schemes in the Asia-Pacific region and examines if any can be opened to humanitarian migrants who may otherwise become targets for migrant smugglers and/or human traffickers. It collects and analyses multiple sources of migration and asylum data from the United Nations, the International Labour Organization, and the member states of the Bali Process to demonstrate the current status of labour migration. It also reviews national legislation, various visa schemes, and bilateral agreements in order to understand how states have regulated labour migration in the region. Six countries are selected to highlight some of the distinctive characteristics and challenges in using labour migration as an alternative pathway for asylum seekers. It concludes that labour migration in its current form is not adequate as a complementary pathway for refugees unless further protective measures are in place. However, a hybrid humanitarian and economic migration stream could be developed with the aim of protecting vulnerable humanitarian migrants before facilitating their labour. Australia is in a good position to lead the discussion through the Bali Process and the Global Compacts on refugees and migrants.

Introduction

Asylum seekers and displaced persons have long been targets for migrant smugglers and human traffickers, especially in the Asia-Pacific region. Finding safe and legal pathways for the movement of asylum seekers and displaced persons has, therefore, become increasingly urgent.

In recent years, the member states of the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime (Bali Process)[1] have shown a greater understanding of the need to expand legal pathways as an alternative solution for refugees and irregular migrants in the region. In a statement released at the 2016 Ministerial Meeting of the Bali Process, member states said:

Ministers reinforced the need to expand safe, legal and affordable migration pathways, including labour migration and family reunification programs, to provide an alternative to dangerous, irregular movement. Ministers encouraged members to consider how labour migration opportunities can be opened up to persons with international protection needs.”[2]

Legal pathways for safe, orderly, regular, and responsible migration is a key commitment adopted at the UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants held in New York in September 2016. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a policy paper that same month outlining alternative pathways for refugees including labour migration, study, family reunion as well as other humanitarian visas and private sponsorships.[3] Canada has implemented a private sponsorship program where five or more citizens or permanent residents can sponsor a refugee living abroad.[4] Australia trialled a community proposal pilot in 2013 and the Human Rights Commission and Refugee Council recommended alternative pathways.[5] Complementary pathways for refugees is also one of the main themes for a Global Compact for Migration to be concluded in 2018.

For labour migration to be used as an alternative pathway for refugees, the skills of those refugees will need to be in demand in the host country. Host countries might also offer induction training courses for refugees to ensure successful integration. Governments can assist private companies to sponsor refugees by providing incentives, including in the form of reduced visa fees. Ensuring refuges meet security and character requirements will remain a major challenge and government will need to work with international partners and local community leaders to address it.

This working paper aims to contribute to the policy discussion on complementary pathways for refugees and asylum seekers among the member states of the Bali Process. It examines whether present legal labour migration schemes can be opened to humanitarian migrants who may otherwise become targets for migrant smugglers and/or human traffickers. It defines the terms and identifies data and methodology used in this paper, before presenting an analysis of current labour migration stocks and flows in the Asia-Pacific. It then reviews national migration legislation in major labour migrant host and sending countries, as well as bilateral agreements and other practical arrangements, including memorandum of understanding (MOU) arrangements. Six countries in the region are used to highlight distinctive characteristics in their labour migration policies. It concludes by identifying challenges and opportunities in existing labour migration mechanisms in the region, and provides policy recommendations for governments, business, and civil society to promote safe and legal migration in the Asia-Pacific.

Data and methodology

In this paper, irregular migration is defined as an “emerging pattern of mass cross-border movements that occur outside of a domestic or international migration regime”.[6] It includes undocumented labour migration (such as economic migrants without work permits, and visa overstayers and misusers), trafficking in persons, migrant smuggling and, arguably, asylum seeking. Labour migration includes both skilled and labour migrants as the profiles of irregular migrants in the region are unclear. Some may have specific skills and knowledge that are required in potential host countries while others may not have sufficient skills and need vocational training before being accepted as labour migrants as a complementary pathway.

Data used for this paper include the 2016 International Labour Migration Statistics Database in the ASEAN by the International Labour Organization (ILO),[7] the 2015 Asia-Pacific Migration Report by the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific,[8] and government statistics on labour migration flows in the Asia-Pacific. For the domestic legal mechanisms and bilateral arrangements on labour migration, the 2015 migrant stock data was collected from the UN Population Division,[9] and primary data from publicly available government websites of the selected countries examined in the paper. The 2015 UN migrant stock data used in this paper does not include the family members of primary labour migrants. Due to the limit on precise data collection and the clandestine nature of irregular migrants that are not captured in official statistics, the numbers in this analysis are almost certain to be lower than in reality.

The paper reviews existing labour migration mechanisms of six Asia-Pacific countries as a baseline study on how the international community, especially the member states of the Bali Process, could improve alternative pathways for refugees and asylum seekers. The countries are the Philippines and Myanmar as migrant-sending countries; Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia as sending and receiving countries; and New Zealand as a migrant-hosting country.

Labour migration stocks and flows

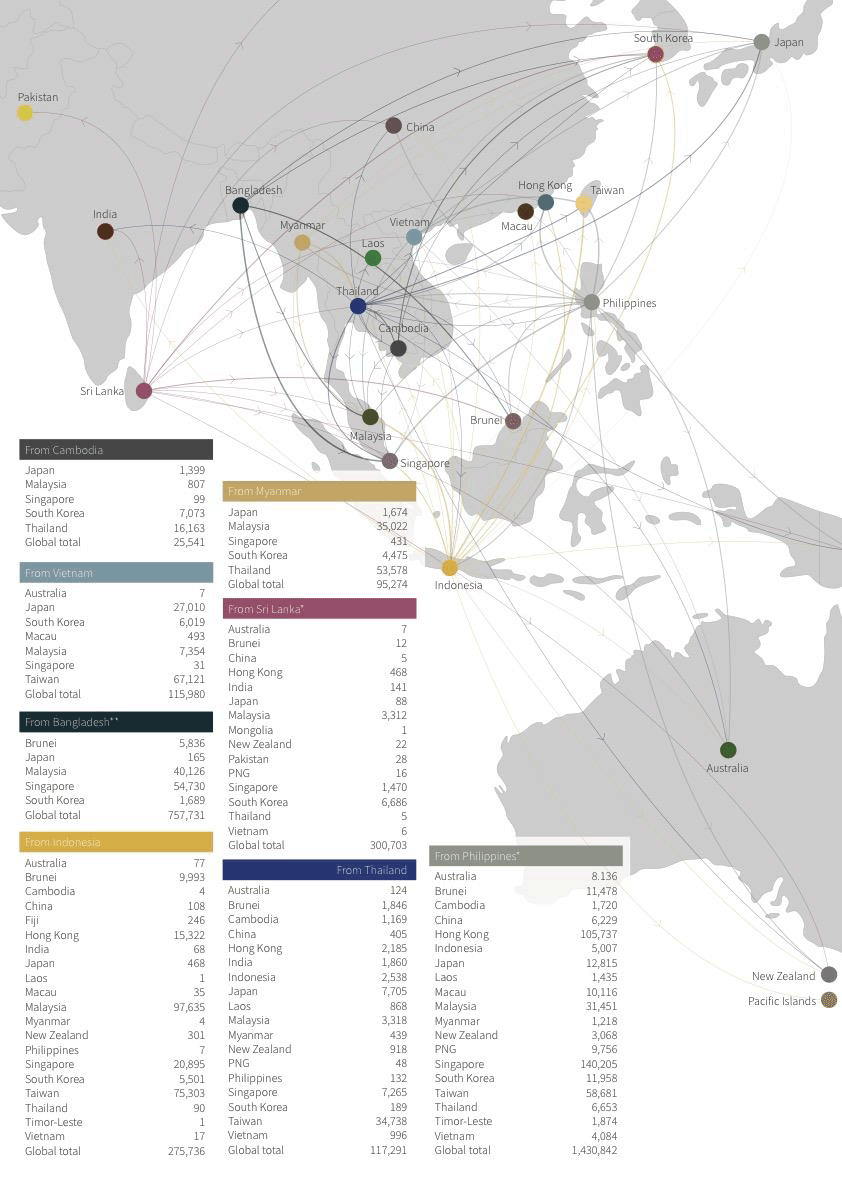

Figure 1 shows the 2015 labour migration flows among selected migrant-sending countries in Southeast Asia. While India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka are major sources of labour migrants from South Asia, and China is a major source country from East Asia,[10] Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Cambodia send a large number of migrant workers from Southeast Asia. These migrant workers go to relatively more advanced economies such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia, Australia, Japan, and South Korea.

Figure 1: Labour migration flows in Southeast Asia, selected countries, 2015

Notes: * 2014 data (2015 data unavailable); ** 2016 data (2015 data unavailable)

Source: International Labour Organization, 2016 International Labour Migration Statistics Database in ASEAN, June 2016; Bangladesh Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training; Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment

The Philippines, Indonesia, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Vietnam are migrant-sending countries whose nationals migrate both to their immediate neighbours and to more developed countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand to seek employment. Most migrants work in mid- to low-income sectors such as fisheries, agriculture, construction, hospitality, services, domestic work, or health care.

Labour-migration trends show gender division in migrant-sending countries. Some countries send more male migrant workers overseas than females: Cambodia (61.2 per cent are male), Myanmar (80.5 per cent), Thailand (80.5 per cent), and Vietnam (66.7 per cent).[11] Indonesia and the Philippines[12] sent a higher proportion of female migrant workers, many of whom are foreign domestic workers. Many Southeast Asian women migrate to Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, Japan, and South Korea as foreign brides through social networks or professional match-making companies. Marriage migrants are usually heavily involved in domestic and care work but such labour is not captured in labour migration statistics since marriage migration is not considered as labour migration and domestic work is not included in the formal definition of work.

Most labour migrants are young, of working age and healthy. UN data indicates that the median age of international migrants in Asia is 35 years.[13] Receiving countries often have age requirements for labour migrants. In South Korea, for example, workers from Sri Lanka must be aged between 18 and 39.[14]

Economic insecurity is the most obvious cause for labour migration in the Asia-Pacific region. All of the economies in the Asia-Pacific with a per capita GDP of less than $10 000[15] are sending countries, while high-income countries are predominantly receiving countries.[16] As such, labour migration in the Asia-Pacific is closely related to the low development levels of sending countries and asymmetric income levels between sending and receiving countries within the region. High levels of unemployment and poverty in sending countries also act as push factors. For example, it is estimated that Filipino households that are able to send a family member overseas are three times more likely to rise above the poverty line than those that do not.[17] If this income gap persists alongside economic opportunities and business demand in receiving countries, intra-regional labour migration flows will continue.

Demographic changes and ageing populations in developed countries are also significant factors in labour migration. Statistics indicate that countries with high migrant worker populations tend to also have ageing populations. For example, in Hong Kong, Japan, China, and South Korea, the number of young workers (aged 20 to 39 years) declined between 2010 and 2015. Within the same period, these countries have also attracted large inflows of migrant workers to help fill labour shortages. In contrast, major sending countries such as Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Nepal, Pakistan, and the Philippines have all experienced growth in their population of 20 to 39 year olds.[18] Declining fertility rates in countries such as Japan and South Korea[19] is also a factor in labour migration, meaning foreign workers are needed to help meet labour shortages.[20]

Interestingly, there is an overlap between migrant-sending countries and the origin countries of asylum seekers. For example, in Southeast Asia, both Myanmar and Indonesia are migrant-sending countries as well as the origin for many asylum seekers in the region. Conversely, major migrant-receiving countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia are also refugee-hosting countries.[21] The Philippines, one of the major migrant-sending countries, is an exception to this trend as it was not a source of asylum seekers in 2017, but conditions can quickly change if there is an internal armed conflict. The key conclusion here is that asylum seekers go to countries where their fellow labour migrants have been going, using existing social networks.[22]

More broadly in the Asia-Pacific, the scale is bigger but it also shows similar trends on the strong nexus between labour migration and asylum seeking. The top ten countries of origin for refugees seeking asylum in the Asia-Pacific at the end of 2016 were Afghanistan, Myanmar, Syria, China, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. The top refugee-hosting countries in the region were Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Thailand, Australia, and Indonesia.[23]

Before considering labour migration as an alternative pathway for asylum seekers, it is first necessary to look at existing labour migration mechanisms in the Asia-Pacific.

Domestic and international legal frameworks for labour migration

This section provides an overview of key national legislation and visa types for labour migration as well as the respective bilateral agreements on labour migration in selected countries in the Asia-Pacific. If labour migration were to be facilitated as an alternative pathway for refugees, it has to meet both international humanitarian and local business demand. For refugees, this alternative pathway can guarantee a right to work and empower them with skills wherever they go, settle or return next. For migrant-receiving countries and businesses, they would need to see the benefits of hosting refugees as a business model or corporate social responsibility. Selected countries include the Philippines and Myanmar as migrant-sending countries; Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia as sending and receiving countries; and New Zealand as a migrant-hosting country.[24]

The ILO found that almost 70 per cent of international labour migration arrangements in Asia are in the form of an MOU and only 15.4 per cent of these are in the form of formal bilateral agreements.[25] Table 1 summarises the MOUs, Inter-Agency Understandings (IAUs) and Pilot Worker Schemes (PWSs) that exist in the Asia-Pacific region. PWSs and IAUs are only used by Australia and New Zealand for Pacific Islanders specifically. Malaysia and South Korea have a number of MOUs with South and Southeast Asian countries. MoUs are important indicators of where migrant-hosting countries such as Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Malaysia, and Thailand see the benefits of having bilateral labour migration arrangements. These are mostly on an ad hoc basis that can be renewed after a few years of trial.

Table 1: Bilateral arrangements on labour migration in Asia-Pacific

|

|

Australia |

Bangladesh |

Indonesia |

Malaysia |

Myanmar |

New Zealand |

Philippines |

South Korea |

Thailand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bangladesh |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

Brunei |

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cambodia |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

MOU |

MOU |

|

China |

MOU |

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

Fiji |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

IAU |

|

|

|

|

Hong Kong |

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

|

India |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indonesia |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

MOU |

MOU |

|

|

Japan |

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

Kiribati |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

IAU |

|

|

|

|

Laos |

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

|

MOU |

|

Malaysia |

|

MOU |

MOU |

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

|

Mongolia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

Myanmar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

MOU |

|

Nauru |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

New Zealand |

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

Nepal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

Pakistan |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

Papua New Guinea |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

IAU |

MOU |

|

|

|

Philippines |

|

|

MOU |

|

|

MOU |

|

MOU |

|

|

Samoa |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

IAU |

|

|

|

|

Solomon Islands |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

IAU |

|

|

|

|

South Korea |

|

MOU |

|

|

MOU |

|

MOU |

|

MOU |

|

Sri Lanka |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

Taiwan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

|

MOU |

|

Thailand |

|

|

|

MOU |

MOU |

|

|

MOU |

|

|

Timor Leste |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

Tonga |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

IAU |

|

|

|

|

Tuvalu |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

IAU |

|

|

|

|

Vanuatu |

PWS |

|

|

|

|

IAU |

|

|

|

|

Vietnam |

|

|

|

MOU |

|

|

|

MOU |

MOU |

Source: International Labour Organization, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific

The Philippines

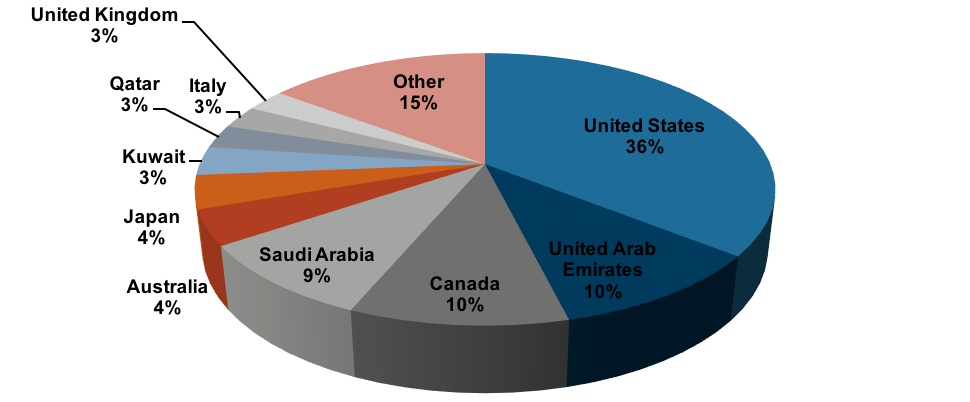

The Philippines sends a large number of workers overseas in both skilled and labour markets. Most go to more developed countries through legal channels with workers’ protections (Figure 2).

The Philippines has a long history as a migrant-sending country and therefore has relatively well-established protection mechanisms in its legal system. The country has amended its Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act a number of times since it was enacted in 1995 to include more protective measures for its overseas workers.[26] The Philippines has MOUs with more developed economies in the region such as Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, and Taiwan.[27] The MOUs prescribe job sectors for foreign workers, along with age and health tests for prospective applicants.

Figure 2: Out-migration from the Philippines, 2015

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, International Migration 2015 Highlights (2016), http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf

While generally considered as a major migrant-sending country and not a source of asylum seekers, the Philippines has in the past granted amnesty to irregular migrants. In 1995, the number of irregular migrants was estimated at 70 000.[28] The government responded by introducing the 1995 Alien Social Integration Act, which granted legal resident status to qualified unlawful non-citizens. The Act regularised irregular migrants, but also served as a means for the government to raise funds. Illegal aliens who had entered the country prior to 1992 could pay a fee of 100 000 pesos (A$2700) in exchange for permanent resident status. It was estimated that 40 per cent of such aliens took advantage of this amnesty program, netting the government around A$39 million in fees. During this period, most of those who applied for amnesty were from China and Taiwan.[29]

With a history of religious and ethnic conflicts in the country, a mass exodus of asylum seekers could be triggered in the future. If that were to happen, asylum seekers are likely to use existing migration and diaspora networks overseas, including in the United States, United Arab Emirates, Canada, and Australia. As a country with a considerable Muslim population and being geographically close to Myanmar, the Philippines is also a potential destination country for asylum seekers from Pakistan, Syria, Iraq, and Myanmar. However, a lack of viable employment opportunities means it may not attract skilled refugees who could otherwise use regular economic migration streams as an alternative pathway.

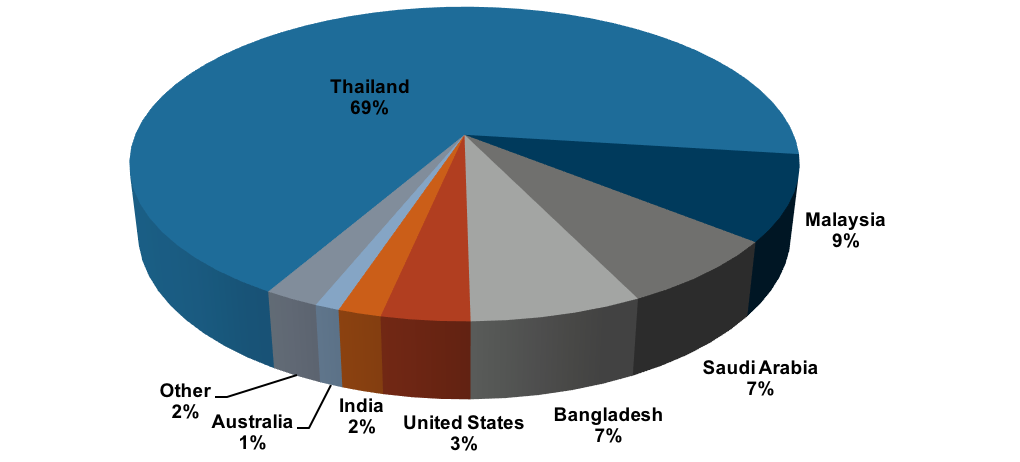

Myanmar

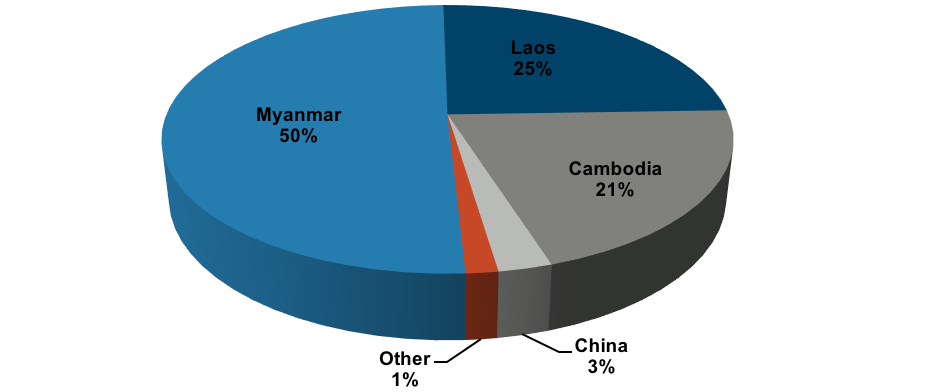

Unlike the Philippines, Myanmar is both a major migrant-sending and refugee-originating country in the Asia-Pacific region. Most migrants and asylum seekers go to their immediate neighbours: Thailand, Malaysia or Bangladesh (Figure 3). The figures below do not capture the large number of undocumented migrants, including asylum seekers, along Myanmar’s porous borders with China, Thailand, and Bangladesh.

Figure 3: Out-migration from Myanmar, 2015

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, International Migration 2015 Highlights (2016), http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf

While the 1999 Law relating to Overseas Employment (Law No 3/99) regulates the employment of Myanmar’s citizens who are working overseas, it does not provide full protection for its workers, or require migrant agents to be registered or prohibit exploitation.[30] Its legal framework is not mature enough to protect its overseas workers, much less asylum seekers, especially ethnic minorities who escape from ongoing persecution from the regime. Since Aung San Suu Kyi came to power, the country’s democratic standards have improved. Yet, the Burmese military’s treatment of ethnic minorities and religious ethnic tensions have still created a mass exodus of Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar’s borders.[31]

Myanmar concluded MOUs with Thailand in 2003 and South Korea in 2008. The MOU with Thailand defines the term of employment as two years, which may be extended by another two years. However, the total employment period cannot exceed four years.[32] It does not limit the industries within which Myanmar migrants can work. The MOU also focuses on integrating irregular migrants from Myanmar.[33] Unlike the Philippines, Myanmar has yet to establish protection mechanisms for workers going overseas, including from potential exploitation by employers or recruitment agencies.

Indonesia

In 2015, 68 per cent of Indonesian migrants went to other Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, and United Arab Emirates for work (Figure 4). In the past decade, undocumented Indonesian migrants in Malaysia were granted amnesty, and were therefore regularised as lawful migrants.[34] It is unknown how many among them were asylum seekers. Similarly, Indonesia’s neighbours, Malaysia and Thailand, host a large number of irregular migrants and often grant amnesty to undocumented migrants, incorporating them through formal mechanisms to monitor and regulate migration. The overall conditions in the region means that host countries benefit from legalising irregular migrants, including long-term asylum seekers. They can formally contribute to the host country’s economy and community security. Amnesty to a small number of asylum seekers who have been in the country for an extended period, who pose no harm to society, and who are willing to contribute to the host community should be considered as a special one-off complementary pathway.

Figure 4: Out-migration from Indonesia, 2015

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, International Migration 2015 Highlights (2016), http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf

Indonesia’s Law on Immigration (Law No 6/2011) regulates the entrance and departure of individuals within Indonesian territory,[35] immigration control,[36] and immigration detention.[37] The Regulation of the Minister of Manpower and Transmigration No 6 of 2013 facilitates the placement of Indonesian workers overseas by requiring a representative to act on behalf of a licensed placement operator in the receiving country.[38] The Regulation also outlines the reporting obligations of the relevant parties,[39] and the processes for dispute settlement.[40] Government Regulation No 4 of 2013 sets out the procedures for the employment of Indonesian migrant workers.[41] Indonesia has MOUs with a number of countries,[42] including Japan where it sends its registered nurses and certified care workers. MOUs normally specify the worker’s age, language proficiency, and health tests.

As both a migrant sending and receiving country, Indonesia has basic protective mechanisms in place for migrant workers. By Presidential Decree, the government has also established an integrated team for the protection of Indonesian workers overseas. This team is responsible for evaluating the problems faced by overseas Indonesian workers, and making recommendations to resolve them. It is also responsible for evaluating the policy and legal framework relating to the placement and protection of emigrant workers, as well as reviewing existing MOUs between Indonesia and receiving countries.[43] In addition, Indonesia ratified the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families in 2012, strengthening its commitment to international standards and the protection of workers’ rights.

Thailand

In 2015, half of Thailand’s migrants were from neighbouring Myanmar (Figure 5). A large number of migrants and asylum seekers are not documented. Along the Thai–Burma borders, many ethnic minorities such as Karen, Kachin, Mon, and Shan have lived in camps for prolonged periods, seeking refuge. Another 46 per cent of Thailand’s migrants are from neighbouring countries, Laos and Cambodia.

Thailand has tried to legalise its irregular migrants from neighbouring countries. It entered into MOUs with Cambodia and Myanmar in 2003 and with Laos in 2002. The MOUs define the terms of employment for migrants as two years with a possible extension of another two years. The focus of Thai legislation is to legalise irregular economic migrants from Cambodia and to integrate them into the local legal framework. In 2015, Thailand and Laos entered into another MOU that focused on the elimination of the trafficking of women and children.[44] Additionally, trade unions in Thailand and Cambodia also signed an MOU in November 2013 on the protection of migrant workers’ rights.[45]

Figure 5: In-migration to Thailand, 2015

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, International Migration 2015 Highlights (2016), http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf

In practice, Thailand has been carrying out alternative ways to accommodate asylum seekers from Myanmar but outside its legal framework. The danger of allowing informal alternative pathways is that the practice is arbitrary and entirely in the hands of the executives, and therefore not guaranteed in the country’s legal framework with access to justice and protection. For example, the Thai government has allowed irregular migrants, including asylum seekers, to stay and work during stable times. This position, however, has changed over the past few years under the military government which has applied stricter rules on immigration. Since 2014, the Thai government has deported irregular migrants from Myanmar and Cambodia.[46]

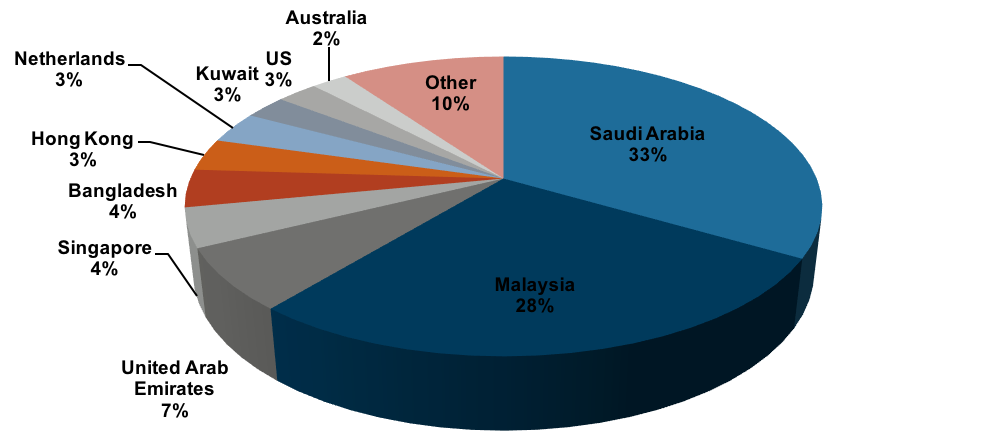

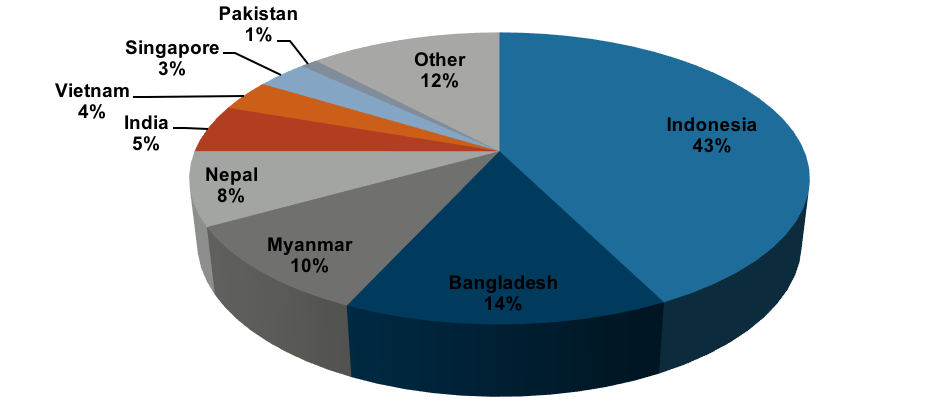

Malaysia

In 2015, 67 per cent of Malaysia’s migrants originated from Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Myanmar (Figure 6). They are also in the top ten source countries for refugees seeking asylum in the region. This number does not capture the large number of Rohingya asylum seekers who are waiting for their refugee status to be determined by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) while working in unregulated economic sectors. Malaysia is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and does not recognise the Rohingyas as refugees. There are almost 58 000 Rohingyas registered with UNHCR in Malaysia, but it is estimated 90 000 Rohingyas already live in the country.[47]

Figure 6: In-migration to Malaysia, 2015

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, International Migration 2015 Highlights (2016), http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf

Malaysia’s Employment (Restriction) Act was enacted in 1968 and amended in 1988.[48] Similar to Thailand’s Alien Working Act, the Employment (Restriction) Act regulates work permits, registration of foreign workers, and restrictions for non-Malaysian citizens. Malaysia has two different tracks for skilled and labour migration. For skilled migration, a foreign applicant needs a letter from their employer. For labour migrants, however, there are a number of restrictions such as gender, age (between 18 and 45 years old), and industry. Some industries are only open to migrants from certain countries. Foreign workers from Thailand, Cambodia, Nepal, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, the Philippines (males only), Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan can work in all sectors. However, workers from India can only work in construction, service, agriculture, and plantation industries. Male workers from Indonesia cannot work in manufacturing, while their female counterparts can work in all sectors. Migrants from Bangladesh can only work in plantations.

All foreign domestic workers must be female, be between 21 and 45 years old, meet religious criteria, and come from approved countries, namely Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, the Philippines, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and India. All prospective employers must also submit applications prior to hiring foreign domestic workers. Labour migrants cannot bring their families and must meet a character test and health requirements. This work permit can be for a period of up to ten years, with no possibility of attaining permanent residency.

While Malaysia has MOUs with a number of countries including Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam,[49] it does not have one with Myanmar where most resident refugees originate. In its MOU with Bangladesh and Cambodia, Malaysia allows businesses in the service, construction, farming, plantation, manufacturing, and domestic work sectors to hire foreign workers between 18 and 45 years of age.[50]

Malaysia is undergoing a pilot scheme that gives refugees the right to work. In February 2017, the government announced a project granting 300 Rohingya refugees the right to work in the country’s plantation and manufacturing sectors.[51] A full-scale evaluation has not been conducted yet but civil society has already raised concerns that this alternative pathway for Rohingya refugees is another form of labour exploitation.[52] For labour migration to be a complementary pathway for refugees, proper protection mechanisms should be in place. Whether Malaysia provides such mechanisms largely remains questionable.

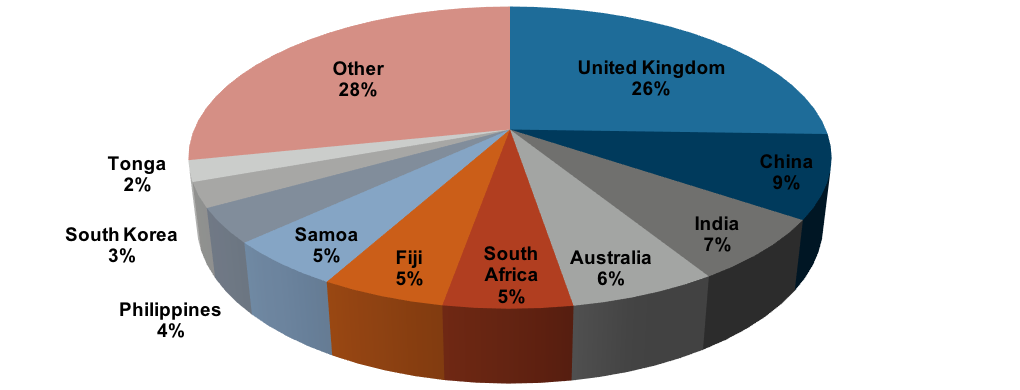

New Zealand

New Zealand is a migrant-receiving country, hosting migrants from more than 60 countries, with the top source countries in the Asia-Pacific being China, India, Fiji, Samoa, the Philippines, South Korea and Tonga. However, as seen in Figure 7, New Zealand also receives migrants from refugee source countries such as Pakistan and Myanmar.

Figure 7: In-migration to New Zealand, 2015

Country of Origin

|

Country of Origin |

No of Migrants |

Country of Origin |

No of Migrants |

No of Migrants |

Country of Origin |

No of Migrants |

||

|

United Kingdom |

265,014 |

Sri Lanka |

9,956 |

Switzerland |

3,185 |

Tuvalu |

1,474 |

|

|

China |

92,602 |

Canada |

9,950 |

Pakistan |

2,961 |

Nepal |

1,465 |

|

|

India |

69,800 |

Ireland |

9,398 |

Afghanistan |

2,540 |

Hungary |

1,421 |

|

|

Australia |

65,161 |

Zimbabwe |

8,416 |

Chile |

2,503 |

Sweden |

1,402 |

|

|

South Africa |

56,396 |

Thailand |

8,023 |

Romania |

2,319 |

Ukraine |

1,402 |

|

|

Fiji |

54,815 |

Hong Kong, China |

7,334 |

Myanmar |

2,200 |

PNG |

1,399 |

|

|

Samoa |

52,640 |

Cambodia |

6,826 |

Italy |

2,044 |

Tokelau |

1,390 |

|

|

Philippines |

38,756 |

Vietnam |

6,393 |

Poland |

2,019 |

Austria |

1,340 |

|

|

South Korea |

27,640 |

Iraq |

5,698 |

Saudi Arabia |

1,951 |

Czech Republic |

1,337 |

|

|

Tonga |

23,291 |

Russia |

5,679 |

Croatia |

1,795 |

Egypt |

1,324 |

|

|

United States |

22,300 |

Singapore |

5,579 |

Argentina |

1,770 |

Colombia |

1,197 |

|

|

Netherlands |

20,589 |

Indonesia |

5,105 |

Kenya |

1,714 |

Ethiopia |

1,187 |

|

|

Malaysia |

16,991 |

Niue |

4,364 |

Kiribati |

1,533 |

Somalia |

1,147 |

|

|

Cook Islands |

13,460 |

France |

3,905 |

Bangladesh |

1,530 |

Serbia |

1,103 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total 1,039,736 |

|

||

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, International Migration 2015 Highlights (2016), http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf

New Zealand’s Immigration Act of 2009 regulates rules on visas, deportation, appeals and other proceedings, as well as detention and relevant immigration offences.[53] There are comprehensive visa categories for both skilled migrants and labour migrants from certain nationalities. For skilled migrants, there is a points-based visa system towards permanent residency, where factors such as age, work experience, qualifications, and an offer of skilled employment are considered. Migrants can bring their family members to New Zealand, but must meet the language, health, and character requirements. New Zealand also has a Long Term Skills Shortage List Work Visa, under which migrants are required to have specific work experience, qualifications, and occupational registration to work in a listed sector. This list includes jobs in construction, engineering, finance and business, health and social services, ICT electronics and telecommunications, recreation, hospitality and tourism, science, and trades.[54] This visa is initially offered for 30 months, but after two years, migrants can also apply for permanent residency. New Zealand allocates 300 spots per year for highly-skilled young applicants between 20 and 35 years, who agree to live and work in the country for nine months. They can later apply for a longer-term visa or permanent residence as skilled migrants. New Zealand has also implemented a Student and Work Visa for a period of six months to four years for those seeking practical work experience or wanting to complete study or training.

New Zealand’s labour migration streams are directly tied to job shortages in its labour market. For example, the Seasonal Employer Limited Visa offers 7500 temporary visas per year for a term of up to seven months, and the Fishing Crew Work Visa is offered when there is no New Zealand national able to perform the job in the fishery sector. In terms of bilateral arrangements, New Zealand has MOUs or IAUs with the Philippines, Hong Kong, Fiji, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu, some of which allow work in the horticulture and viticulture industries.[55]

The country also offers special categories of permanent residence or temporary residence to certain nationalities in specific occupations. Samoans are offered 1100 places per year while the Pacific Access Category Visa allows Kiribati, Tuvaluan, Tongan, and Fijian citizens to register for a ballot in which successful applicants are granted an indefinite right to stay. Each year 75 Kiribati, 75 Tuvaluan, 250 Tongan and 250 Fijian registrations are drawn. The age requirement is 18 to 45 years old. Pitcairn Islanders are also offered permanent residency. Some see this as a form of complementary pathway for potential environmental refugees in the region. With climate change and other man-made disasters increasingly becoming the source of forced migration, this active and targeted migration program offered to Pacific Islanders could also be a good model for alternative pathways for humanitarian migrants or environmental refugees.

What is unique about New Zealand’s skilled migration and labour migration schemes are the visa categories targeting certain nationalities with specific occupations. For example, for Chinese citizens, New Zealand offers 200 places for chefs, 200 for traditional medicine practitioners, 150 for Mandarin teacher’s aides, 150 for Wushu Martial Arts coaches, and 100 for tour guides per year. These visas are valid for three years and only require character tests. However, they cannot bring their spouses or children. Similar schemes exist for Thai chefs, Japanese interpreters, Indonesian chefs (100), Indonesian halal slaughterers (20), Indonesian Bahasa teachers’ aides (20), Filipino registered nurses (100), Filipino farm managers (20), Filipino engineering professionals (20), Vietnamese chefs (100), and engineering professionals (100). It also allows 50 South Koreans and 60 Chileans a year, supported by their home governments, to undertake vocational study or work placements in primary sector industries for up to 12 months. Additionally, 1000 Chinese and 200 South Korean citizens can work in New Zealand for up to three years, provided that they are qualified in a skilled occupation (as defined in the “China Skilled Workers’ Instructions”[56] and “Republic of Korea Special Work Occupation”[57]).

New Zealand has one of the most sophisticated and well-designed economic migration streams. It also has a well-established humanitarian migration program meaning it may not need to open additional skilled or labour migration categories to accept refugees through complementary pathways.

Challenges and opportunities for complementary pathways in Asia-Pacific

Greater regional consensus will be required for the creation and expansion of complementary pathways for refugees in the Asia-Pacific. While states will need to ensure that existing labour migration does not replace humanitarian programs or undermine national security, they should also recognise the role that alternative pathways play in contributing to the local economy and community development as well as protecting refugees’ right to work. At the same time, governments will need to consider the moral, political, and economic dimensions of opening labour migration as an alternative pathway for humanitarian migrants. For a hybrid labour humanitarian migration program to work for both the hosting society and refugees, governments would need to consult with local business communities and civil society.

Promoting legal pathways for safe and orderly migration raises a question about the treatment of humanitarian migrants, who need international protection, as economic assets.[58] The visa types studied in this paper demonstrate that labour migration mechanisms are built with the primary aim of filling gaps in skills and labour shortages in the host country’s domestic labour market, not for providing humanitarian protection for migrants. Existing labour migration schemes therefore do not serve as an appropriate alternative pathway for refugees. However, a hybrid humanitarian and economic migration stream could be developed with the aim of protecting vulnerable humanitarian migrants before facilitating their labour. This new stream should not replace existing quotas for humanitarian programs and should empower refugees, not cherry-pick their skills.

Host countries also have legitimate concerns over potential threats that migrants and refugees may pose to their society and national security. Arguments are often framed around perceptions of threat and questions of identity.[59] To address these security concerns, governments need to strengthen bilateral and multilateral mechanisms for information sharing on identity, criminal records, and past involvement with violent or terrorist organisations. Sharing biometric data and travel logs of individuals who pose security threats, as identified by intelligence and security organisations, is an area where countries can work together effectively. While human rights concerns about information sharing, privacy and individual liberty are valid, national security is an essential prerequisite for safe and legal migration as well as guaranteeing alternative and sustainable pathways for refugees.

Human rights groups have been raising issues with inadequate protection for migrant workers in Southeast Asia for many years. While pre-departure and post-arrival programs can help improve the existing protective mechanisms for migrant workers, these options are not available for refugees. Source countries for refugees such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, Myanmar or Bangladesh not only endanger refugees but also have weak economies such that the country cannot provide business environments or jobs for working-age populations. Politics, security, and the economy are indivisible. Further, migrant- and refugee-hosting countries in Southeast Asia such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia are also developing countries where adequate protection mechanisms are not always in place and political environments can fluctuate depending on the leadership. Only advanced economies and democracies such as Australia and New Zealand, and to some extent, South Korea and Japan, can offer access to a broader range of human rights protections.

Some of the advanced economies have post-arrival programs for incoming migrants. As indicated in Table 2 below, Australia and New Zealand provide support in language, vocational training, and settlement grants. South Korea and Malaysia offer employment training upon arrival. In South Korea, limited interpreting services (in ten different languages) are available to workers who attend a Foreign Workforce Counselling Centre. The Korean Federation of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises provides training to workers in manufacturing sectors.[60] Training courses are offered to migrant workers from Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar in the Samut Prakan Province of Thailand. Free language tuition is offered through civil programs such as the Saphan Siang Youth Ambassador campaign, which promotes better understanding between Thais and issues faced by migrant workers. There are also programs in Thailand where volunteer migrant health workers act as interpreters between migrant workers and healthcare providers.

The International Organization for Migration has compiled best practices in the design and management of pre-departure and post-arrival programs.[61] Australia has one of the best post-arrival support programs. The government provides up to 510 hours of free English language tuition to eligible migrants on temporary visas, including Business Skills (Provisional), Safe Haven Enterprise and Skilled — Regional Sponsored visas.[62] Targeting permanent migrants, the government also provides grants to private service providers to help settle new arrivals in Australia.[63] This allows migrants to access job opportunities and to integrate more effectively into civil society. Australia’s Fair Work Ombudsman also has the power to investigate workplace complaints.

Table 2: Post-arrival programs by migrant-receiving countries[64]

|

Programs |

Thailand |

Malaysia |

Indonesia |

South Korea |

Australia |

New Zealand |

|

Employment training on arrival |

Limited |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Access to country information |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Free language tuition provided by government |

Limited |

No |

Unknown |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Language support when dealing with government |

Limited |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Limited |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Free vocational training for working-age job seekers |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Limited |

Yes |

No |

|

Grants to private organisations to help settle migrant workers |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Resources for employers to help settle migrant workers |

Yes |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Limited |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Dispute management support for migrant workers and employers |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: See endnote 64 for full list of sources

Engagement with businesses and civil society

Utilising labour migration as a complementary pathway for refugees is an innovative idea that requires a whole-of-nation approach. Governments should actively work with businesses to come up with best practices to build business models that encourage greater corporate social responsibility by hiring qualified and eligible refugees. With closer and regular consultation with local businesses on their workforce needs and security concerns, governments and businesses can learn from each other and work together to protect and empower refugees in their communities. Socially responsible businesses can monitor their peers for any potential malpractices or abuses of foreign workers and refugees.

The pilot program for granting 300 Rohingyas the right to work in Malaysia is a good test case. The program was initiated by UNHCR staff.[65] The rationale behind the program was that, first, there was local business demand in manufacturing and plantation for foreign labour and, second, Rohingya refugees were already residing in the country and working in the shadow economy as irregular migrants. Malaysia does not recognise refugees. Many other Southeast Asian states have not signed the Refugee Convention in fear of more asylum seekers entering their territory uncontrolled. To use labour migration as an alternative pathway for refugees in Southeast Asia, governments would need support from their business communities. As of May 2017, not many businesses are registered to join the pilot program and only half of the quota has been filled.[66]

Civil society is another important stakeholder for complementary pathways. Service providers can help integrate newly arrived migrants and offer them induction or training courses with government support. Human Rights groups can monitor the working conditions and general welfare of refugees. Academics can conduct in-depth research on their local integration and contribution to their own communities. Governments can work with these various stakeholders to assess and update the program. Information can be shared with other states.

Regional development

If successful, labour migration as a complementary pathway for refuges can go beyond its personal and community development and bring broader effects on regional development. Critics rightly caution that selecting skilled refugees has a long-term risk of creating a ‘brain drain’ in countries of origin.[67] However, new skills and knowledge acquired from labour migration as a complementary pathway in the host country can generate new networks and information between origin and host communities and increase communication and trade between the two. It can benefit both migrants and host countries. Complementary pathways through employment can allow refugees to integrate into the host society. When and if refugees want to return to their countries of origin, they can help rebuild the community with new skills and contribute to post-conflict resolution. For host countries, giving refugees alternative pathways through jobs can divert asylum seekers’ choice of dangerous and illegal routes of arrivals through smuggling to safe and legal migration, which is more predictable and manageable. Governments must outsmart and offer a better, safer, and legal business model than refugee-smugglers who seek profits by exploiting desperate asylum seekers who pay. Visa fees for alternative pathways will be a critical factor for both asylum seekers and local businesses who will sponsor them. The fees will need to be more affordable than smuggling fees.

There are potential conflicts between source and host countries in using labour migration as an alternative route to settlement for refugees. Its selectiveness may create a tension between the two governments that can strain political and diplomatic relations. Receiving refugees is fundamentally a political decision. Malaysia has publicly criticised the Myanmar government for mistreating Rohingyas.[68]

Strengthening the Bali Process

The Bali Process can play a significant role in strengthening the regional mechanism to stop migrant smuggling and human trafficking. Australia can contribute in a number of ways to safe and legal migration in the Asia-Pacific. First, Australia, as one of the two co-chairs of the Bali Process, can initiate expanding its mandates to include forced migration, recognising forced and irregular migration are highly interrelated. The 2016 Declaration acknowledged the growing scale and complexity of irregular migration challenges, including smuggled or trafficked asylum seekers. Recognising and incorporating mixed migration in its formal mandates and procedures would mean member states can be better equipped with adequate policies to tackle irregular and forced migration in the region within the Bali Process framework.

Second, Australia can continue to offer legal training and technical assistance to major migrant-sending countries such as Myanmar and Bangladesh to strengthen their domestic legal frameworks on labour migration, bilaterally and multilaterally through the Bali Process. In particular, regulating mass movements of people for economic or humanitarian purposes will help migrants to operate within legal norms and governments to monitor their progress in a transparent manner. This would also disincentivise migrant smugglers and instead encourage entrepreneurial individuals to use legal mechanisms. Through the Bali Process, Australia can initiate working-level discussions about what best hybrid economic and humanitarian migration mechanisms can coexist, in close coordination with both migrant sending and receiving countries.

Third, Australia can help strengthen the legal migration regimes in the Asia-Pacific to protect vulnerable migrants, whether they are foreign labourers or refugees, and guarantee access to legal justice for the protection of minimum human rights and labour standards. No country is free from human rights abuses. Australia is strong in establishing criminal justice among the member states of the Bali Process. The next steps forward will be to help set up a system that ensures migrant-centric access to legal migratory procedures, justice mechanisms, and victim protection.

Fourth, legal training and technical assistance must include how to simplify the migration process, making it easier and more accessible for labour migrants and reduce administrative fees so that asylum seekers do not fall into the hands of traffickers or smugglers who purport to offer a faster, easier and cheaper service than conventional routes. Making the entire process of labour and humanitarian migration easy, accessible, and affordable is beneficial not only for migrants to safely move to another country but also for the state to stop irregular migration and make national borders more secure.

Fifth, Australia is in a good position to lead international cooperation with other countries in the Asia-Pacific in terms of data gathering and intelligence sharing about trafficking and smuggling networks. In the past few years, Australia has established its international reputation on strong border security, which is one significant pillar of safe and legal migration that the region aims to achieve as a common goal. Australia can lead on best practices for border security that is consistent with international law and humanitarian principles for protecting refugees.

Sixth, Australia can work with business leaders and private sponsors who are willing to offer temporary placements for refugees and asylum seekers. Pilot programs have been in place in Australia and in Malaysia since 2013. The effectiveness and sustainability of these complementary pathways should be evaluated. Hybrid visa types can be further discussed in consultation with business leaders, humanitarian migration experts, civil society representatives and, most importantly, refugees themselves who have gone through the pilot programs. Australia can lead this discussion and offer a highly innovative and pragmatic solution to refugee/migration crises in the region and beyond.

Seventh, Australia should continue to lead the discussion on complementary pathways. No one system or pathway will fit all refugees and asylum seekers. There should be more debates on various legal pathways for refugees, including student visas or family reunions. Where necessary, temporary labour migration should also be considered. Governments should also be willing to take criticism on its pragmatic and functionalist approach. Public debates on the subject are much needed.

At the upcoming United Nations Global Compacts on refugees and migrants, Australia can be a regional voice from the Asia-Pacific, recognising the current global challenges of mixed migration of refugees and irregular migrants and bring innovative solutions to safe, legal, and affordable pathways to vulnerable humanitarian and economic migrants. The emphasis on the role of the private sector in protecting forced and other irregular migrants is central.

Conclusion

This working paper reviewed existing labour migration regimes in the Asia-Pacific region to see whether there are any potential complementary pathways for humanitarian migrants in the future. There are significant overlaps between the countries where refugees seek asylum and where economic migrants have been looking for employment. Both humanitarian and economic migrants move to their immediate neighbouring countries to seek protection and employment. Most migrant workers from Myanmar cross the borders to Thailand. Indonesian workers go to Malaysia. Many Karen, Kachin, Mon, Shan, and Rohingya refugees live in Thailand and Malaysia. A much smaller number of refugees venture into more advanced economies such as Australia, Japan, South Korea, or New Zealand.

Legal labour migration mechanisms in the Asia-Pacific are mostly temporary in nature with certain restrictions on: (1) the number of migrants; (2) nationalities; (3) age and sex; and (4) within designated industries. Most countries that receive labour migrants also require candidates to pass health and character tests. Often, migrants are also required to have certain levels of language proficiency. South Korea even has weight and height requirements for labour migration. Of the countries considered in this paper, New Zealand has the most comprehensive framework for labour migration, targeting certain nationalities and occupations in a given period with potential permanent settlement pathways. It also has labour migration schemes specifically targeting Pacific Islanders.

Labour migration is designed to mobilise foreign labour and talents, not to offer protection for vulnerable migrants. The existing labour migration mechanisms often do not fully comply with international labour or human rights standards. In order to use labour migration as an alternative pathway for refugees, a new hybrid program needs to be invented: a business-sponsored and government-administered humanitarian and labour migration program that is safe, legal, and affordable for refugees and asylum seekers. For this, governments need to consult with local business communities that will hire refugees and civil society that will provide induction and training courses with government subsidies.

The Bali Process is an ideal regional mechanism to discuss the current labour migration mechanisms and potential hybrid humanitarian and labour migration programs. Australia is in a perfect position to lead this discussion at the upcoming Global Compacts for refugees and migrants in 2018. It has tested a community support program and helped establish strong criminal justice mechanisms to stop human trafficking and migrant smuggling. The time is ripe for Australia to move forward and lead a new initiative on complementary pathways for refugees.

Acknowledgements

This working paper series is part of the Lowy Institute’s Migration and Border Policy Project, which aims to produce independent research and analysis on the challenges and opportunities raised by the movement of people and goods across Australia’s borders. The Project is supported by the Australian Government’s Department of Home Affairs. The views expressed in this working paper are entirely the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy, the Department of Home Affairs or the Australian Government.

This is the final paper in the series of Analyes and working papers delivered under the Migration and Border Policy Project. The author would like to thank the Department of Home Affairs for their generous funding.

Thank you also to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. Special thanks to Daniel Thambar for his excellent research assistance, Anthony Bubalo for his kind guidance throughout the Migration and Border Policy Project, and Lydia Papandrea for her professional copy-editing.

About the author

Dr Jay Song is a Senior Lecturer in Korean Studies at the Asia Institute at the University of Melbourne and former Program Director of the Migration and Border Policy Project at the Lowy Institute.

Notes

[1] Established in 2002, the Bali Process is an official international forum that facilitates policy discussion and information sharing to help address issues relating to people smuggling, human trafficking and related transnational crime. It has 48 member states, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC), as well as a number of observer countries and international agencies: http://www.baliprocess.net/.

[2] The Bali Process, “Sixth Ministerial Conference of the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime: Co-Chairs’ Statement”, Bali, 23 March 2016, Paragraph 10, http://www.baliprocess.net/UserFiles/baliprocess/File/BPMC%20Co-chairs%20Ministerial%20Statement_with%20Bali%20Declaration%20attached%20-%2023%20March%202016_docx.pdf. See also The Regional Support Office of the Bali Process, “Pathways to Employment: Expanding Legal and Legitimate Labour Market Opportunities for Refugees”, Bangkok, 1–2 September 2016, http://www.baliprocess.net/news/summary-pathways-to-employment-expanding-legal-and-legitimate-labour-market-opportunities-for-refugees/.

[3] OECD, “Are There Alternative Pathways for Refugees?”, Migration Policy Debates, No 12, September 2016, https://www.oecd.org/els/mig/migration-policy-debates-12.pdf.

[4] Government of Canada, “Groups of Five — Sponsor a Refugee”, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/help-outside-canada/private-sponsorship-program/groups-five.html.

[5] Australian Human Rights Commission, Pathways to Protection: A Human Rights-Based Response to the Flight of Asylum Seekers by Sea (Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission, 2016).

[6] Jiyoung Song and Alistair Cook eds, Irregular Migration and Human Security in East Asia (London: Routledge, 2014), 8.

[7] International Labour Organization, International Labour Migration Statistics Database in ASEAN, June 2016, http://www.ilo.org/asia/WCMS_416366/lang--en/index.htm.

[8] UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2015 Asia-Pacific Migration Report: Migrants’ Contributions to Development, http://www.unescap.org/resources/asia-pacific-migration-report-2015.

[9] UN Population Division, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/.

[10] “Trends in International Migrant Stock: Migrants by Destination and Origin”, UN Population Division, accessed 18 April 2017, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates15.shtml.

[11] Statistics for Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam are based on 2015 data. Myanmar’s statistics are based on 2014 data (2015 data is unavailable): International Labour Migration Statistics Database in ASEAN, International Labour Organization Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, accessed 9 April 2017, http://apmigration.ilo.org/asean-labour-migration-statistics.

[12] This observation is based on labour stock data for 2015: Philippines Statistics Authority, 2016 Gender Statistics on Labour and Employment (Philippines Statistics Authority, 2016), 8–2, https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/GSLE%202016%20PUBLICATION%20%281%29.pdf. The Philippines does not disaggregate by gender when publishing statistics on labour flows.

[13] UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, International Migration Report 2015: Highlights, ST/ESA/SER.A/375, 2016, 12, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf.

[14] “Employment Permit System”, Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment, accessed 17 April 2017, http://www.slbfe.lk/page.php?LID=1&MID=118.

[15] 2011 international dollars, adjusted for purchasing power parity.

[16] UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, Asia-Pacific Migration Report 2015, ST/ESCAP/2738, 50, http://www.unescap.org/resources/asia-pacific-migration-report-2015.

[17] Geoffrey Ducanes, “The Welfare Impact of Overseas Migration on Philippine Households: Analysis using Panel Data”, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 24, No 1 (2015), 79–106.

[18] UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, Asia-Pacific Migration Report 2015, ST/ESCAP/2738, 50, http://www.unescap.org/resources/asia-pacific-migration-report-2015.

[19] Gavin Jones, Underlying Factors in International Labour Migration in Asia: Population, Employment and Productivity Trends (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2008), 16, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_160329.pdf.

[20] Bhakta Gubhaju and Yoshie Moriki-Durand, Fertility Levels and Trends in the Asian and Pacific Region (UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2003).

[21] “Population Statistics”, UNHCR, accessed 29 December 2017, http://popstats.unhcr.org/en/persons_of_concern.

[22] Ignacio Correa-Velez, Adrian Barnett and Sandra Gifford, “Working for a Better Life: Longitudinal Evidence on the Predictors of Employment Among Recently Arrived Refugee Migrant Men Living in Australia”, International Migration 53, Issue 2 (2013), 321.

[23] UNHCR Population Data – Asylum Seekers, http://popstats.unhcr.org/en/asylum_seekers.

[24] The Bali Process, Sixth Ministerial Conference of the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime (Bali: The Bali Process, 23 March 2015), Paragraph 10, http://www.baliprocess.net/UserFiles/baliprocess/File/BPMC%20Co-chairs%20Ministerial%20Statement_with%20Bali%20Declaration%20attached%20-%2023%20March%202016_docx.pdf. See also, The Regional Support Office of the Bali Process, Pathways to Employment: Expanding Legal and Legitimate Labour Market Opportunities for Refugees (Bangkok: The Regional Support Office of the Bali Process, 1–2 September 2016), http://www.baliprocess.net/news/summary-pathways-to-employment-expanding-legal-and-legitimate-labour-market-opportunities-for-refugees/.

[25] Piyasiri Wickramasekara, Bilateral Agreements and Memoranda of Understanding on Migration of Low Skilled Workers: A Review, (Geneva: International Labour Organization, March 2015), 21, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_385582.pdf.

[26] International Labour Organization, Database of National Labour, Social Security and Related Human Rights Legislation, http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.listResults?p_lang=en&p_country=PHL&p_count=563&p_classification=17&p_classcount=26.

[27] “Bilateral Labour Agreements (Landbased)”, Philippine Overseas Employment Administration, accessed 17 April 2017, http://www.poea.gov.ph/laborinfo/bLB.html.

[28] UN Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Migration News, Vol 3, No.7, July 1996, http://www.un.org/popin/popis/journals/migratn/mig9607.html.

[29] Rayna Bailey, Global Issues: Immigration and Migration (New York: Infobase Publishing, 2008), 110.

[30] Law relating to Overseas Employment (Law No. 3/99), http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.listResults?p_lang=en&p_country=MMR&p_count=116&p_classification=17&p_classcount=6.

[31] Jiyoung Song, “Myanmar’s Muslims: A Long Way Down Aung San Suu Kyi’s To-Do List”, The Interpreter, 16 August 2016, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/myanmars-muslims-long-way-down-aung-san-suu-kyis-do-list.

[32] Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the Kingdom of Thailand and the Government of the Union of Myanmar on Cooperation in the Employment of Workers, 21 June 2003, http://apmigration.ilo.org/country-profiles/mou-on-cooperation-in-employment-of-workers-1, Article IX.

[33] Ibid, Article III.

[34] Expert Workshop on Safe and Legal Migration in Asia-Pacific, organised by the Bali Process Regional Support Office, 23 May 2017.

[35] Law on Immigration (Law No. 6/2011), Chapter III, http://ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=89341&p_country=IDN&p_count=610.

[36] Ibid, Chapter VI.

[37] Ibid, Chapter VIII.

[38] Regulation of the Minister of Manpower and Transmigration No 6 of 2013, http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=95237&p_country=IDN&p_count=617&p_classification=17&p_classcount=100. The English translation of the legislation is not available online.

[39] Regulation of the Minister of Manpower and Transmigration No 6 of 2013, Chapter III.

[40] Ibid, Chapter IV.

[41] Government Regulation No 4 of 2013, http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=95250&p_country=IDN&p_count=617&p_classification=17&p_classcount=100.

[42] Database of MOUs/BLAs and Standard Employment Contracts, International Labour Organization Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, accessed 17 April 2017, http://apmigration.ilo.org/country-profiles/mou_list?country=ID.

[43] Presidential Decree No 15/2011, Article 2, http://ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=91164&p_count=97760.

[44] Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and the Government of the Kingdom of Thailand on Cooperation to Combat Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, 13 July 2005, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/genericdocument/wcms_160934.pdf.

[45] Memorandum of Understanding Between Trade Unions in Cambodia and Trade Unions in Thailand on Protection of Migrant Workers’ Rights, 11 November 2013, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/genericdocument/wcms_319025.pdf.

[46] Human Rights Watch, “Thailand: Migrant Worker Law Triggers Regional Exodus”, 7 July 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/07/thailand-migrant-worker-law-triggers-regional-exodus; Steve Finch, “Is the Thai Junta Targeting Cambodian Migrants?”, The Diplomat, 26 June 2014, https://thediplomat.com/2014/06/is-the-thai-junta-targeting-cambodian-migrants/; Khin Oo Tha, “Thousands of Myanmar Migrants Return from Thailand”, The Irrawaddy, 30 June 2017, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/thousands-myanmar-migrants-return-thailand.html.

[47] “Figures at a Glance”, UNHCR Malaysia, accessed 3 June 2017, https://www.unhcr.org.my/About_Us-@-Figures_At_A_Glance.aspx; “Rohingya Leader: 90,000 Already in Malaysia Willing to Work”, Radio Free Asia, 8 December 2016, http://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/malaysia-rohinga-12082016142041.html.

[48] Employment (Restriction) Act 1968 (Act 353), http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.listResults?p_lang=en&p_country=MYS&p_count=205&p_classification=17&p_classcount=5.

[49] Database of MOUs/BLAs and Standard Employment Contracts, International Labour Organization Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, accessed 17 April 2017, http://apmigration.ilo.org/country-profiles/mou_list?country=MY. See also: “Bilateral Diplomacy”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia, accessed 17 April 2017, http://www.kln.gov.my/web/guest/bd-bilateral_treaties. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs website contains a list of all bilateral agreements which Malaysia has entered into, but it does not include links to these agreements.

[50] Bdnews24.com, ‘Bangladesh Signs MOU with Malaysia to Send 1.5 million Workers”, 18 February 2016, http://bdnews24.com/economy/2016/02/18/bangladesh-signs-mou-with-malaysia-to-send-1.5-million-workers. See also, Ministry of Human Resources, “Malaysia-Bangladesh MOU Not Affected by Decision to Freeze Recruitment of Foreign Workers — Riot”, 22 February 2016, http://www.mohr.gov.my/index.php/en/news-cutting/435-malaysia-bangladesh-mou-not-affected-by-decision-to-freeze-recruitment-of-foreign-workers-riot.

[51] UN High Commissioner for Refugees, “UNHCR Lauds Government Work Scheme for Refugees”, reliefweb, 3 February 2017, http://reliefweb.int/report/malaysia/unhcr-lauds-government-work-scheme-refugees.

[52] Caitlin Wake, ‘Turning a Blind Eye’: The Policy Resonse to Rohingya Refugees in Malaysia, HPG Working Papers (London: Overseas Development Institute, 2016).

[53] Immigration Act 2009 (No. 51), http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.listResults?p_lang=en&p_country=NZL&p_count=685&p_classification=17&p_classcount=13.

[54] New Zealand Immigration, “Long Term Skill Shortage List”, accessed 17 April 2017, http://skillshortages.immigration.govt.nz/long-term-skill-shortage-list.pdf.

[55] Clause 2.1 of each of the IAUs between New Zealand and each of Fiji, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea.

[56] New Zealand Immigration, “China Skilled Work Occupations”, accessed 17 April 2017, https://www.immigration.govt.nz/new-zealand-visas/apply-for-a-visa/tools-and-information/work-and-employment/china-skilled-work-occupations.

[57] New Zealand Immigration, “Republic of Korea Special Work Occupations”, accessed 17 April 2017, https://www.immigration.govt.nz/new-zealand-visas/apply-for-a-visa/tools-and-information/work-and-employment/republic-of-korea-special-work-occupations.

[58] Khanh Hoang, “The Risks and Rewards of Private Humanitarian and Refugee Sponsorship”, The Interpreter, 16 May 2017, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/risks-and-rewards-private-humanitarian-and-refugee-sponsorship.

[59] Jiyoung Song, “The Migration-Security Nexus in Asia and Australia (Part 4)”, The Interpreter, 6 July 2016, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/migration-security-nexus-asia-and-australia-part-4.

[60] Min Ji Kim, The Republic of Korea’s Employment Permit System (EPS): Background and Rapid Assessment, International Migration Papers (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2015), 41, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_344235.pdf.

[61] International Organization for Migration, Best Practices: IOM’s Migrant Training/Pre-departure Orientation Programs, accessed 28 May 2017, https://www.iom.int/files/live/sites/iom/files/What-We-Do/docs/Best-Practices-in-Migrant-Training.pdf.

[62] “Eligible temporary visas for AMEP”, Department of Education and Training, accessed 28 May 2017, https://www.education.gov.au/eligible-temporary-visas-amep. This entitlement is established by the Immigration (Education) Act 1971.

[63] “DSS Grants Services Directory”, Department of Social Services, accessed 28 May 2017, http://serviceproviders.dss.gov.au/.

[64] Sources for Table 2: Catherine Laws, Heike Lautenschlager and Nilim Baruah, Progress of the implementation of recommendations adopted at the 3rd – 8th ASEAN Forums on Migrant Labour, Background Paper (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2017); Strengthening Post-Arrival Orientation Programs for Migrant Workers in ASEAN, Policy Brief (International Labour Organization, 2015), 22, 27, 30, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/projectdocumentation/wcms_417376.pdf; Min Ji Kim, The Republic of Korea’s Employment Permit System (EPS): Background and Rapid Assessment, International Migration Papers (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2015), 16, 18, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_344235.pdf; Travel Smart — Work Smart (International Labour Organization, 2014), http://www.ilo.org/dyn/migpractice/docs/214/Thailand.pdf; “Employment Permit System”, https://www.eps.go.kr/ph/index.html; Department of Social Services, Beginning a Life in Australia, https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/09_2016/webready_balia_4a_120916.pdf; New Zealand Immigration, “Access Help and Support”, https://www.newzealandnow.govt.nz/move-to-nz/getting-help-support; Department of Education and Training, “Adult Migrant English Program”, https://www.education.gov.au/adult-migrant-english-program-0; Department of Immigration and Border Protection, “Translating and Interpreting Service”, https://www.tisnational.gov.au/; Office of Ethnic Communities, “How Language Line Works”, http://ethniccommunities.govt.nz/story/how-language-line-works; Department of Education and Training, “Skills for Education and Employment”, https://www.education.gov.au/skills-education-and-employment; Department of Social Services, “Skills for Education and Employment”, https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/settlement-and-multicultural-affairs/programs-policy/settlement-services/settlement-grants-program; New Zealand Immigration, “Settlement Services we Support”, https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/what-we-do/our-strategies-and-projects/settlement-strategy/settlement-services-supported-by-immigration-new-zealand; Department of Social Services, New Arrivals — New Connections (Department of Social Services, 2017), https://www.dss.gov.au/settlement-and-multicultural-affairs/publications/new-arrivals-new-connections?HTML; New Zealand Immigration, “Communicating with Migrant Employees”, https://www.immigration.govt.nz/employ-migrants/settle-migrant-staff/resources-for-you; Ministry of Employment and Labor, “Employment Permit System”, https://www.eps.go.kr/ph/index.html; Fair Work Ombudsman, “Visa Holders and Migrant Workers — Workplace Rights and Entitlements”, https://www.fairwork.gov.au/how-we-will-help/templates-and-guides/fact-sheets/rights-and-obligations/visa-holders-and-migrant-workers-workplace-rights-and-entitlements#discrimination; Employment New Zealand, “What Is Mediation”, accessed 28 May 2017, https://www.employment.govt.nz/resolving-problems/steps-to-resolve/mediation/what-is-mediation/.

[65] Fieldwork interview with Richard Towle, UNHCR Representative in Kuala Lumper, Malaysia, August 2017.

[66] Expert Workshop organised by the Bali Process Regional Support Office in Bangkok on 23 May 2017.

[67] OECD, Are There Alternative Pathways for Refugees?, Migration Policy Debates, 2016, https://www.oecd.org/els/mig/migration-policy-debates-12.pdf; Katy Long and Kasumi Takahashi, “Credit Where It’s Due: Ensuring Migration Pathways for Refugees Are Financially Accessible”, May 2017, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55720db4e4b077f61c75d9d2/t/596ce4a020099ea7637ee134/1500308645269/Credit+where+it%27s+due.pdf.

[68] Praveen Menon, “Malaysia PM Opens Thorny Debate in Accusing Myanmar of Genocide”, Reuters, 9 December 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rohingya-malaysia/malaysia-pm-opens-thorny-debate-in-accusing-myanmar-of-genocide-idUSKBN13Y0IY.