The missing middle: A political economy of economic restructuring in Vietnam

Despite impressive economic performance, Vietnam’s strong trade and investment gains have yet to fully overcome the vestiges of its economic past.

- Economic restructuring and greater integration with the international economic system has brought Vietnam impressive gains in wealth, trade, and investment.

- Such efforts have not, however, resolved Vietnam’s ‘missing middle’ or the lack of a productive domestic private sector and the continued dominance of the state-owned sector.

- While these challenges represent a risk to Vietnam’s future growth potential, initiatives such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership provide an opportunity for further trade and investment expansion.

Executive summary

Vietnam’s cautious and sequenced adoption of market institutions has brought more than two decades of impressive economic performance, all while leaving the country’s underlying political economy largely intact. Notably, Vietnam has leveraged greater integration with the international economic system, including through ascension to the World Trade Organization in 2007 and the conclusion of a spate of free trade agreements, as a means of reinforcing domestic change.

Such efforts, however, have not resolved Vietnam’s ‘missing middle’, or the dearth of a productive domestic private sector and the continued dominance of the state-owned sector. As a result, impressive levels of exports and investment have not yet resulted in concomitant gains for domestic value added or linkages to domestic firms. As these challenges represent serious risks to Vietnam’s future growth potential, it is important to find new methods to bolster institutions and reduce the role of state-linked actors. The historical importance of international trade agreements in the Vietnamese system means initiatives such as the rebranded Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership presents an unusual opportunity — both for assisting Vietnam’s current economic restructuring, as well as creating a framework for further expansion of trade and investment with other important economic partners.

Photo: Nguyen Trong Bao Toan/Getty Images

Introduction

Over the past decade, Vietnam has emerged as Southeast Asia’s most intriguing economic story. Not because it is the region’s largest economy (a title that belongs to Indonesia) or its fastest growing (a position that moves between Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos). It is because economic restructuring has brought impressive gains in wealth, trade, and investment — all while leaving the country’s fundamental power structure largely intact.

Successful economic restructuring has, however, also contributed to Vietnam’s primary economic challenge today, namely how to address its ‘missing middle’ — the lack of a productive domestic private sector. Indeed, Vietnam’s tremendous success boosting exports and attracting foreign direct investment has not yet unwound extensive state ownership or forged linkages between export-focused industries and the rest of the domestic economy. As a consequence, Vietnam has struggled to reap the full benefits of its impressive trade and investment performance.

This Analysis begins by providing background on the development of Vietnam’s economy and its transition from a planned economy to one with many market features. It then examines Vietnam’s current economic challenges, including those raised by the US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). It concludes with a discussion of the Australia–Vietnam relationship. The paper includes insights gathered during field research in Vietnam during May and June 2017.

Vietnam at centre stage

In mid-November 2017, the attention of the world’s economic policymakers and analysts fell on the unlikely location of Danang, a coastal city in central Vietnam which hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit. While President Donald Trump’s meetings with world leaders such as Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin attracted the most attention, even more important was a series of meetings in the margins of the summit.

Eleven of the twelve signatories to the TPP (the so-called ‘TPP-11’) met to seek a way forward for the ‘high-quality’ trade agreement, the future of which was thrown into chaos after Donald Trump kept a campaign promise and withdrew the United States from the TPP in January 2017. Vietnam, for its part, initially announced it would depart the agreement but continue to implement the reforms to which it had agreed. Later, however, having already invested heavily in steering many of the agreements through its political system, Vietnam returned to the fold as part of the TPP-11. At Danang, Vietnam signalled its support for the agreement pending greater flexibility for the implementation of its commitments on labour protections.

As the lowest-income member of the TPP, and a country that is heavily dependent on trade, Vietnam provides an important case study for future multilateral trade liberalisation. Integration with the world economy has brought Vietnam impressive gains in wealth, trade, and investment, but has also brought new challenges, including a lack of progress in unwinding state economic ownership, in boosting productivity, and developing a competitive private sector. As a consequence, its economy suffers from a ‘missing middle’, or shortage of private medium-sized enterprises.

Central to the original appeal of the TPP — beyond new access to the US market for Vietnamese exports — was a justification for addressing these challenges. In the context of Vietnamese economic history, such outside agreements have been used to support the implementation of difficult domestic change. As a result, the news out of the Danang APEC summit that the TPP-11 had agreed, in principle, to the core aspects of an agreement — rebranded as the CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership) — was a positive step for Vietnam.

Although the gains that Vietnam can expect under the eleven-nation agreement are not as great as if the United States were included, it will still benefit from expanded trade opportunities, more investment and added ammunition to address some thorny challenges in its domestic economy. Perhaps most importantly, Vietnam will be part of what is likely to be the prime piece of architecture for future multilateral trade liberalisation in the region. Although not a panacea, a framework such as the CPTPP that is predicated on quality domestic institutions and standards would assist Vietnam with its most pressing economic challenges.

Vietnam’s economic journey

Vietnam is one of Southeast Asia’s standout economic performers. It has strong fundamentals with favourable demographics, good income distribution, and attractive human capital compared to similar countries.[1] With a population of more than 90 million and a growing middle class, Vietnam is increasingly emerging as an attractive market in its own right.

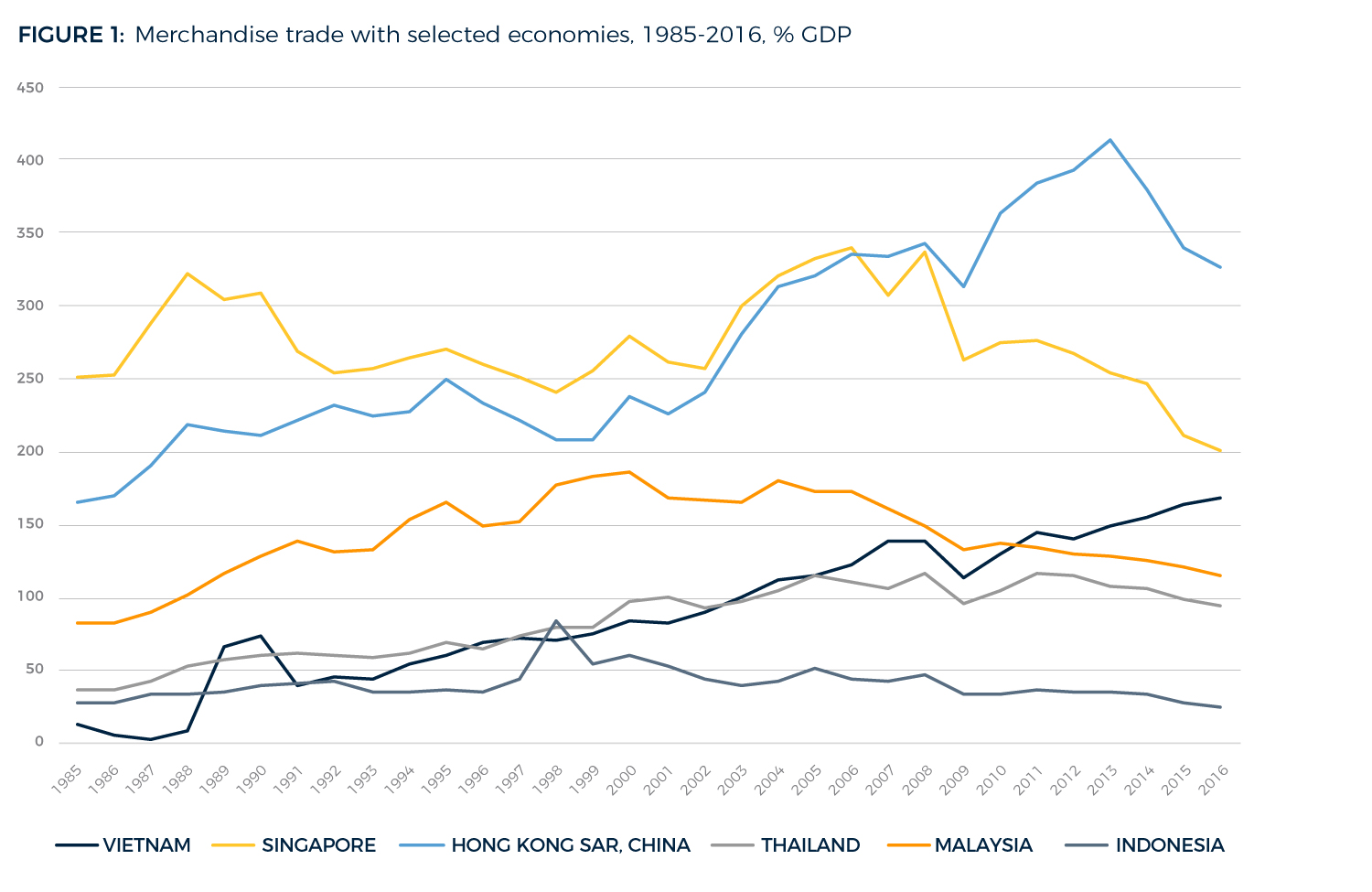

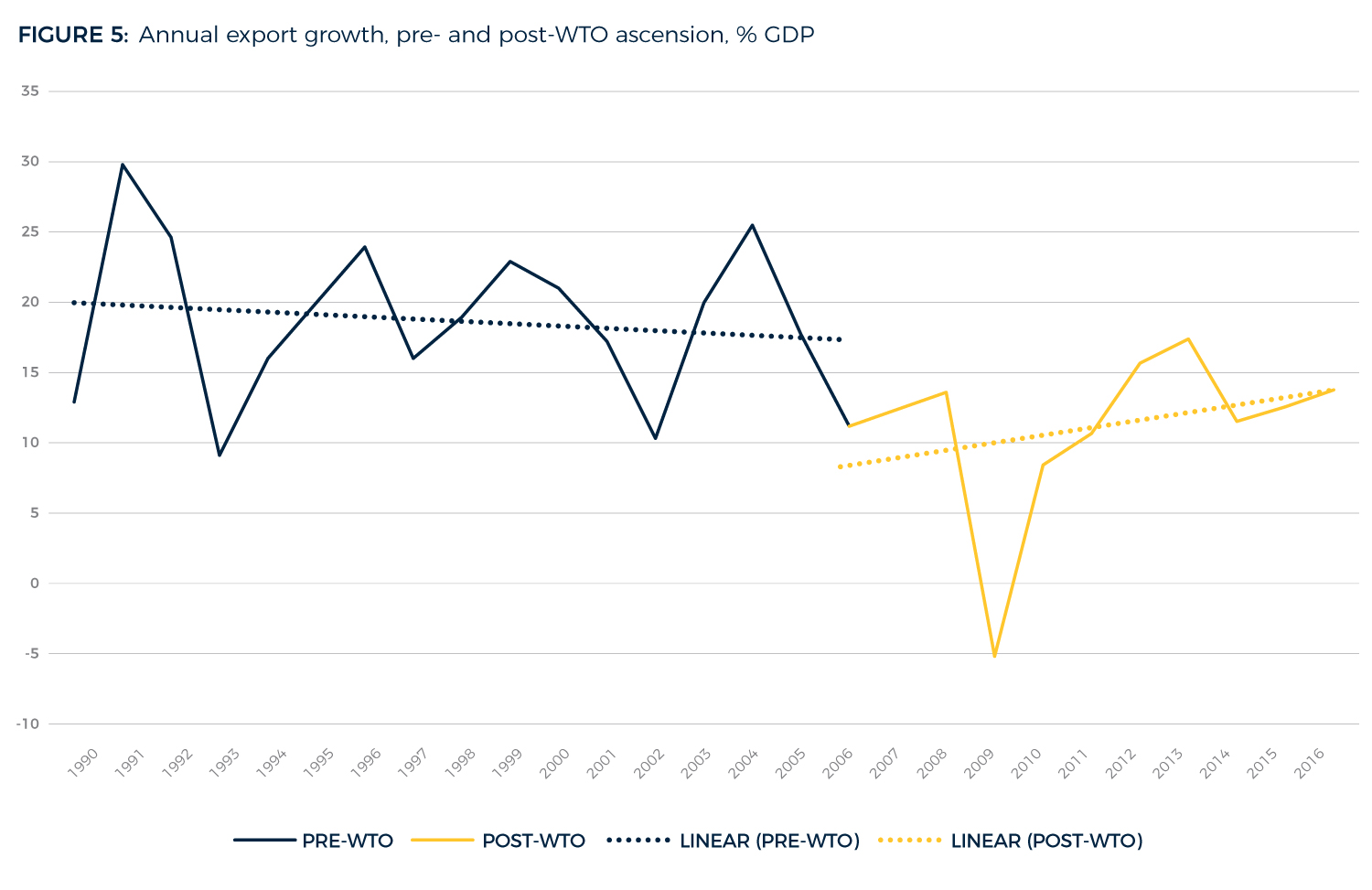

All of this is reflected in Vietnam’s impressive economic track record. The country is rightfully touted as evidence of the potential gains for developing countries that choose openness and trade. During the 2000s, its GDP per capita increased an average of 7.9 per cent per annum.[2] Since 2010, annual growth averaged 6.5 per cent and in 2016 reached 6.4 per cent. After joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007, Vietnam’s exports more than trebled from US$45 billion in 2006 to US$190 billion in 2016.[3] Over the same period, merchandise trade as a share of GDP expanded from 127 per cent in 2006 to 173 per cent in 2016.[4]

Vietnam’s trade dependence is not far behind the city state economy of Singapore (206 per cent of GDP), and well in excess of regional peers such as Malaysia (120 per cent), Thailand (100 per cent), and Indonesia (30 per cent). According to one Vietnamese economic adviser interviewed by the author, “We had no choice and had nothing to bring [to the world market] besides our trade.”[5]

A web of 16 free trade agreements (FTAs) have helped Vietnam become deeply embedded in global value chains.[6] Vietnam’s political stability, low labour costs, favourable tax and investment terms, and FTAs have seen it emerge as an attractive exporter to more developed markets.[7] Vietnam has attracted large amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI), including a record US$15.8 billion in 2016, up 9 per cent from 2015.[8] Technology multinationals such as Intel and Samsung, which assembles nearly one-third of its smartphones in Vietnam, are large investors in the country.[9] Mobile phone handsets and related parts now make up 20 per cent of Vietnamese exports.[10] The country is also the second-largest supplier of apparel to the United States, Japan, and South Korea.[11]

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

Vietnam’s potential is underpinned by the progress it has made on key human development indicators, including maternal health, electrification, and literacy. In 1993, more than half of the population lived in ‘extreme poverty’. Today that rate has fallen to 3 per cent, with more than 40 million people coming out of poverty over the past two decades.[12] As at 2015, Vietnam had achieved its Millennium Development Goal of universal primary education with a net enrolment of 99 per cent, and was well on its way to the same target for lower secondary education.[13] Vietnamese students have thrived particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Vietnam outranks many developed countries in the OECD’s PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) rankings, particularly in science and mathematics.[14]

Such performance is remarkable for a country that 30 years ago was almost completely impoverished. The contrast with Vietnam’s current economic situation, and especially its integration with the global economy, is particularly stark and makes the transformation even more noteworthy. Prior to 1986, central planning was dominant in Vietnam. Private trade and manufacturing was nationalised and collective farming meant most citizens were not permitted private agricultural plots. In 1986, the Communist Party of Vietnam began introducing price and market mechanisms (known as Doi Moi or ‘economic renovation’) aimed at transforming the economy.

The growth of these price and market mechanisms was not the product of a single ‘reform’ moment.[15] Rather it was the accumulation of three decades of incremental change. Policymakers adopted a pragmatic approach to the introduction of market features and loosening the reins of central planning.[16] Three features stand out: leveraging trade and global value chains to grow exports; deploying external commitments to lock in domestically agreed reforms; and restructuring the existing political economy while leaving dominant power structures largely intact.[17]

After reunification in 1975, Vietnam had a largely centrally planned economy, albeit with a considerable informal sector (for example, food vendors, bicycle repairers, hairdressers).[18] Official experimentation with prices and markets began slowly, as some prohibited activities — known as ‘fence breaking’ — were permitted.[19] In agriculture, for example, this included allocating land to farmers and directly contracting for production at prices higher than the plan. Vietnam was then dependent on food imports, and efforts to renovate the agricultural sector not only freed up labour but also generated food commodities that improved the terms of trade.[20] There were also efforts to boost manufacturing and heavy industries such as chemicals and shipbuilding, which were modelled on the systems of South Korea and Taiwan, sometimes with unintended consequences.[21] For example, ill-advised attempts to emulate South Korean chaebol-led industrialisation culminated in the near bankruptcy of state-owned shipbuilder, Vinashin.

Crucially, the introduction of market mechanisms was managed by the state. Fence breaking activities often relied on quasi-official forms of approval or licensing. Early examples of liberalisation took the form of normalising smuggling or illegal trade already sanctioned by local officials — and usually carried out by managers of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Such tacit approvals not only created markets for otherwise illicit commodities, but also for the official positions that controlled these activities.[22] In fact, this coalition of local officials and SOE managers — who were the prime beneficiaries of fence breaking — represented the main force lobbying their more senior party peers to accept these market changes.

The prime beneficiaries of liberalisation were state firms, which under previous collectivisation and central planning controlled most land and assets. State firms expanded rapidly, even amid periodic culls following build-ups of state credit (and, inevitably, bad loans).[23] In the early 2000s, many SOEs were subject to some form of limited privatisation (especially of asset-holding subsidiaries), a policy that was accepted because it furthered the interest of state-connected actors. In the absence of a true commercial class able to acquire and manage divested assets, privatisations ended up funnelling valuable assets, such as land, from SOEs to private companies under the control of these actors.[24] Privatised companies retained their connection to the state, as the government kept nearly two-thirds of SOE shares sold during the main period of privatisations from 2001 to 2011.[25] This was also a feature of the near complete absence of domestic commercial interests, and many SOEs expanded into sectors such as real estate, retail, and banking.[26]

Vietnam also embraced international commerce as a core strategy of its economic renovation. Bilateral trade liberalisation agreements were concluded with the United States in 2001 and the European Union in 2003.[27] Exports expanded as a share of GDP from 30 per cent in 1990 to 50 per cent in 2000 to nearly 94 per cent in 2016.[28] Many in Vietnam talk about how the government has used its international trade and investment agreements as a way of complementing their economic restructuring efforts.[29] Agreements also often came with technical assistance, which made changes even more palatable. As a result, the potential collapse of the TPP during early 2017 hit hard domestically, as those pushing for further economic renovation had pinned their hopes on the commitments and assistance they could expect under the TPP. Not all agreed, however, and the agreement’s generous access to markets such as the United States for large industries including the garment trade was critical for assuaging domestic opponents. Interlocutors in Vietnam bemoaned the loss of the anticipated ‘attitude adjustment’ of officials and vested interests more than any preferential market access that they would have gained from the agreement.

Vietnam’s three pillars of pain

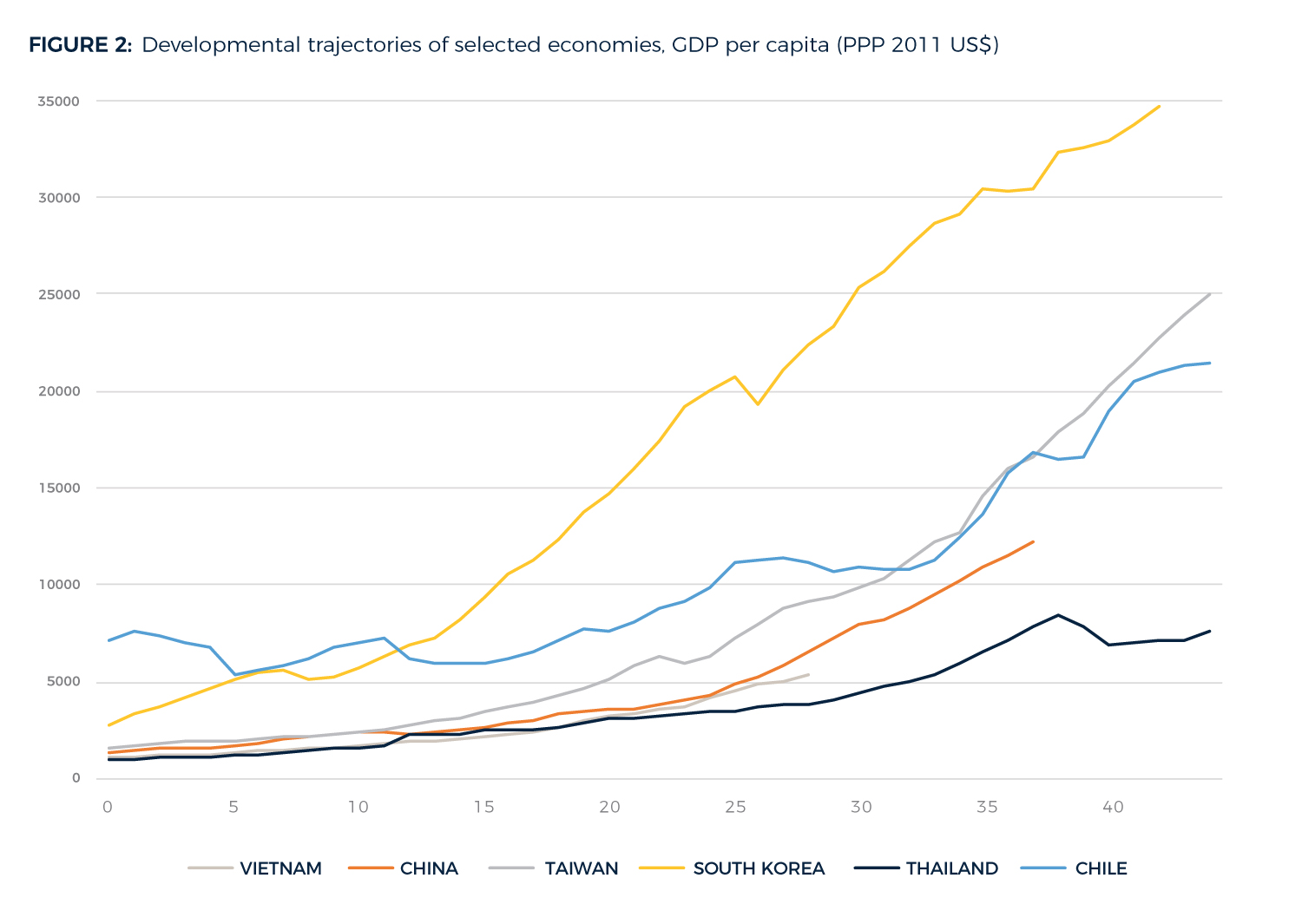

Vietnam’s economy has performed impressively, but it also faces an emerging conundrum. Having already realised the gains from integration with global value chains, demography, capital investment, and macroeconomic stability, Vietnam may struggle to ‘catch up’ to more developed economies before the economic gains from a young population and greater capital investment are exhausted. One World Bank study has found that Vietnam requires an annual GDP growth of 7–8 per cent to reach the current position of Asian economies such as Taiwan and South Korea by 2035.[30] Currently, Vietnam is struggling to reach 6.5 per cent annual growth.[31] It remains in a strong position, but its current relatively young population will age rapidly in the coming decade, and its rate of ageing will be among the highest in the world from 2030 onward.[32]

Notes: Adapted with modification from World Bank; Ministry of Planning and Investment of Vietnam, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy (Washington DC: World Bank, 2016), 18. Base years are 1951 for Taiwan, 1958 for Thailand, 1970 for Chile, 1972 for South Korea, 1977 for China, and 1986 for Vietnam.

Source: Author’s calculation; Penn Tables, Version 9.0

The most pressing challenges are consistent with its need to maintain a high rate of economic growth. Vietnam has undertaken ‘three pillars’ of economic restructuring: resolving bad debts in the banking sector; rationalising the state-owned sector, and improving the quality of public investment. The three issues are closely intertwined.

Bad debt

The economic reforms required in order for Vietnam to join the WTO in 2007 meant it became much easier for capital to enter the country.[33] Vietnamese enterprises, which lacked competitiveness, did not gain from WTO ascension.[34] The subsequent reversal of capital flows saddled the country with a weak currency and high inflation, and revealed a banking system with high rates of non-performing loans. Many of these loans were to Vietnam’s 13 large state corporations and were often extended by private banks owned by these same conglomerates.[35]

Unwinding the debt overhang has proven difficult. The government issued a ‘roadmap’ for bank restructuring in 2012.[36] A handful of weak banks were merged, and in 2013 the Vietnamese Asset Management Company (VAMC), was set up. VAMC swapped non-performing loans at cost from banks in exchange for VAMC-issued ‘special bonds’ that provide collateral for borrowing from the central bank.[37] By June 2015, official non-performing loans fell from more than 17 per cent of total banking assets to less than 4 per cent.[38] The strategy was a success, as it fenced off non-performing loans and allowed most banks to continue operating while avoiding a full-blown crisis.

A similar strategy to arrest lending, discipline renegade banks, and lock down bad loans so the financial sector could, over time, outgrow them was also pursued after breakneck credit expansion in the early 2000s. However, the scale of the debts — likely more than US$20 billion (or 10–15 per cent of GDP) — makes it difficult to outgrow it even with strong economic growth.[39] With the absence of a secondary market for non-performing loans, many banks assume the bad loans will eventually return to their balance sheets.[40]

State-owned enterprises

SOEs are responsible for the largest share of bad loans in Vietnam and were the catalyst for the banking sector’s troubles. Vietnam maintains a majority stake in more than 3000 SOEs. Although they account for around 30 per cent of GDP, and about 40 per cent of total investment, their share of economic activity has not changed since 1990.[41] They also provide less than 5 per cent of total employment;[42] an estimated 92 per cent of employment comes from small private firms.[43] SOEs have consistently grown more slowly and used capital less efficiently than other enterprises, soaking up resources and ‘crowding out’ private sector development in the process.[44]

Addressing the dominance of SOEs would help strengthen banks. The large number of inefficient SOEs are a strain on the financial sector’s efficient allocation of national savings.[45] In November 2015, the National Assembly ratified an economic restructuring plan for 2016–20 with SOE reform and restructuring of the financial sector among its leading priorities. Sensitivity about selling assets cheaply, however, has slowed both SOE privatisation as well as bank restructuring.

Progress can be undermined by Vietnam’s political economy. Most SOEs are not centrally controlled. Local state actors have responded to the privatisation drive by devolving SOEs’ valuable assets such as land into subsidiaries with murky and in many cases quasi-private ownership structures.[46] Land is particularly important, as it also serves as collateral for bank borrowing, often fuelling real estate speculation and cycles of booms and busts. Land use rights are non-permanent and location-bound, and there is no primary market for trading land use rights.[47] Altering land use classifications can be prohibitively expensive, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and citizens. Observers believe more formalised and tradeable land use rights would benefit SMEs, deepen financial inclusion, and help facilitate longer-term borrowing and lower interest rates.[48] However, a more flexible land-use regime would also alter the privileged relationship between SOEs and banks, which would also find it difficult to operate without a ready-made SME sector to provide alternative borrowers.

Improving public investment

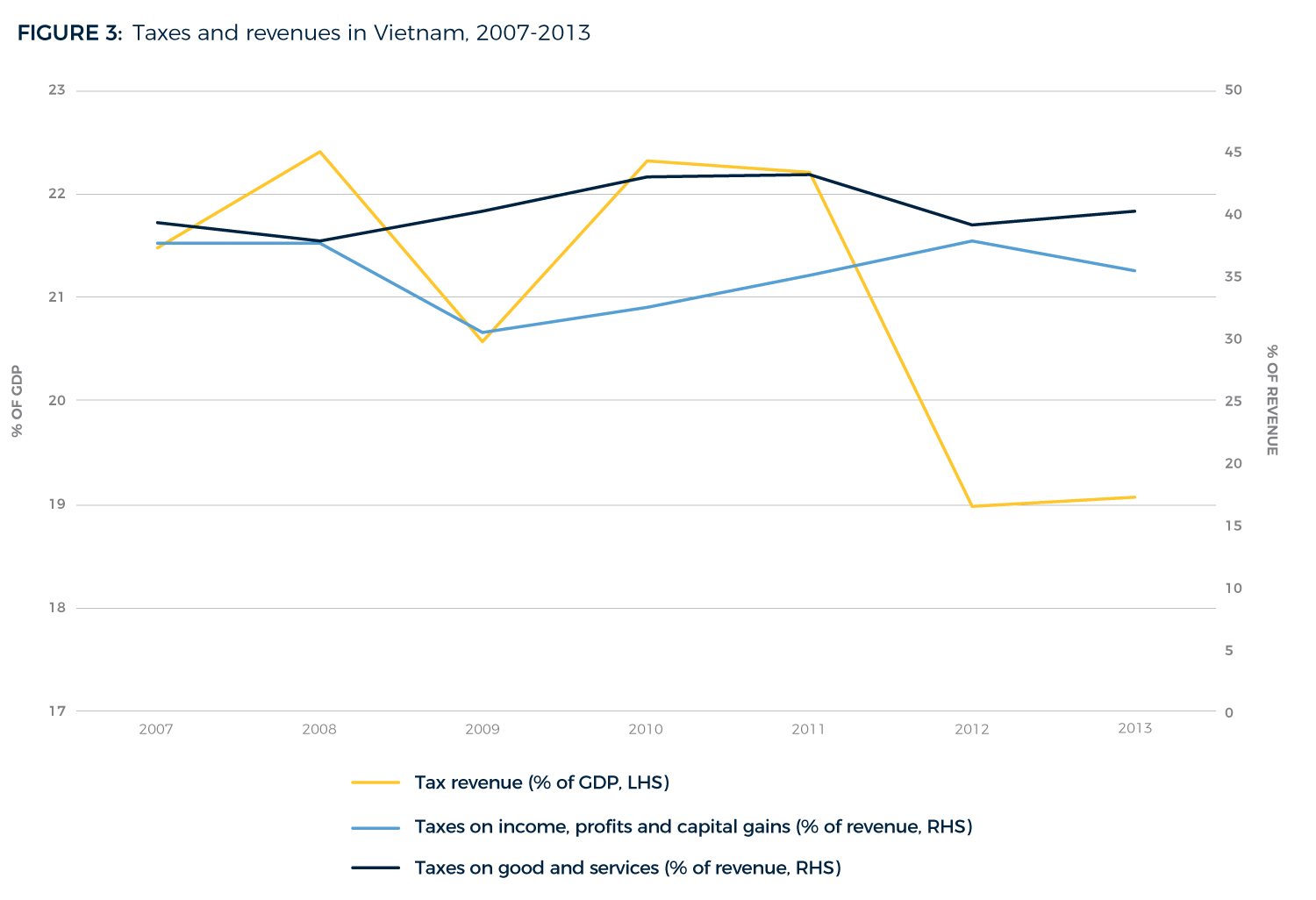

The Vietnamese Government also lacks the fiscal space to write down these non-performing loans or bail out SOEs.[49] With its budget deficit exceeding 6 per cent of GDP for each of the past five years, Vietnam has effectively reached its self-imposed 65 per cent debt-to-GDP ceiling for 2016–18.[50] In fact, this fiscal constraint has seemingly led to some progress on SOE restructuring, with sales of strategic stakes and even initial public offerings for major SOEs announced in 2017.[51] Other sources of revenue remain flat despite strong economic growth, with total tax revenues under 20 per cent of GDP and the share from income and profit taxes a meagre 35 per cent of total tax.[52]

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

Of perhaps greater concern than the fiscal constraint of the debt ceiling is the low quality of existing public spending, much of which takes place at the subnational level. Vietnam’s central transfers are highly progressive and became more so during 2007–11, and have helped drive regional-urban convergence in access to services and measures of welfare.[53] It is widely known, however, that the quality of public investment is often uncoordinated and incoherent because of fragmented governance structures.[54] As a consequence, there is acceptance within government that simply adding cash to an ineffective system without first addressing spending quality would lead to certain waste. There is little serious discussion of expanding the debt ceiling beyond 65 per cent of GDP, which is relatively restrained in contrast to some comparator countries. The continued ballooning of the public sector and a decentralised governance framework also contribute to public investment without adequate accountability and oversight.[55] Changes to the investment regime, including around the time of Vietnam’s ascension to the WTO, led to the decentralisation and streamlining of investment approvals to local authorities. Local governments have in turn aggressively pursued investment, especially FDI.[56] Competition between local governments to attract foreign investment has at times been productive and at times wasteful.[57] One example of waste and duplication has been the number of ports and airports that have been built.[58] Often this is the result of a process in which provincial governments conceive of infrastructure projects and pitch them to central authorities, with approvals sometimes difficult to explain outside of an opaque intra-party process.[59]

Importantly, these contemporary policy challenges — namely, the dominance of SOEs and low quality of public investment — have emerged as a consequence of historical restructuring strategies. Initial fence breaking efforts to introduce prices and markets were successful in large part because they expanded the authority of local officials and affiliated SOEs. As a result, local interests played an important role in persuading central planners that their illicit trade and other prohibited activities could be safely sanctioned and successfully expanded without radically undermining the prevailing political economy.[60] Today, however, analogous power structures may have different priorities. For example, as central planning receded, local governments acquired more responsibilities, which because of budget constraints and a reliance on access fees, led to the empowerment of local SOEs to raise revenues, raise financing for, and develop infrastructure and other politically connected projects.[61]

However, progress is being made. A new Law on Public Investment introduced in 2014 has instituted stronger controls on local government budgeting. Provincial governments now have debt ceilings, although they remain in control of how much and from where they can borrow outside this.[62] The 2015 State Budget Law introduced a medium-term framework for public budgeting. Such measures raise the challenge of balancing the government’s growth target with the need to improve the quality of public investment while continuing investment in economically important items such as infrastructure.[63]

Vietnam’s missing middle

Vietnam’s three restructuring priorities — bad debts in the banking sector, SOE reform, and public investment — are all related to the challenge of the missing middle. Despite Vietnam’s success boosting investment and exports, developing the domestic private sector has proven difficult.

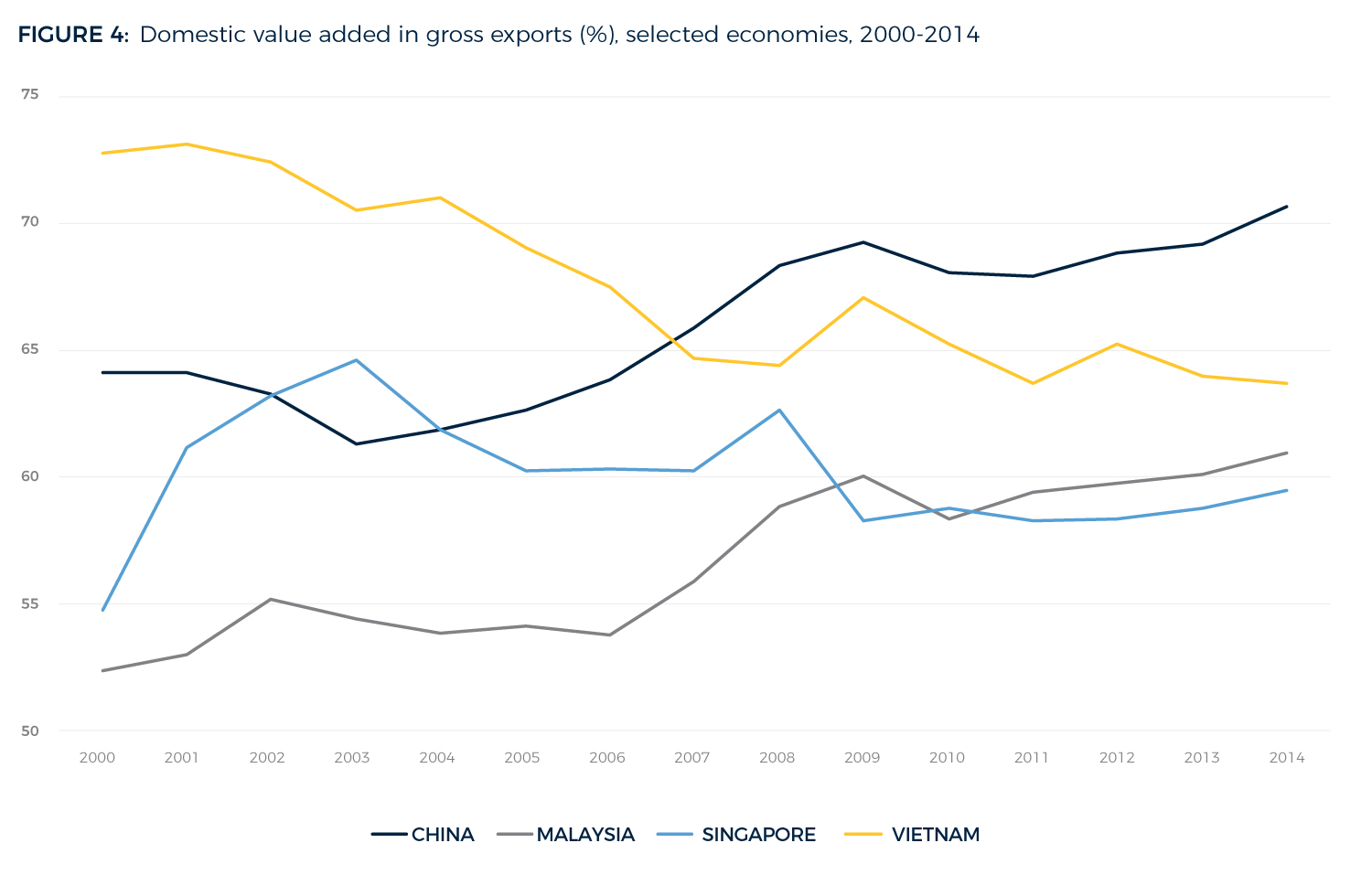

Vietnam’s economic successes have derived from trade and investment liberalisation, and competitive labour and service linkage costs, allowing it to carve out an impressive niche in global production networks. At the same time, however, Vietnam has seen productivity fall, with the largest falls in the domestic private sector. Many export-oriented sectors have limited links to domestic suppliers or service providers. They also rely on global supply chains with a large share of imported inputs, often across several steps that experts describe as structural supply chain ‘breaks’. In the case of Vietnam, these features may become especially pronounced because it has derived much of its competitiveness from taxation, investment facilitation, and low labour costs.

Source: OECD, “Domestic Value Added in Gross Exports”, https://data.oecd.org/trade/domestic-value-added-in-gross-exports.htm

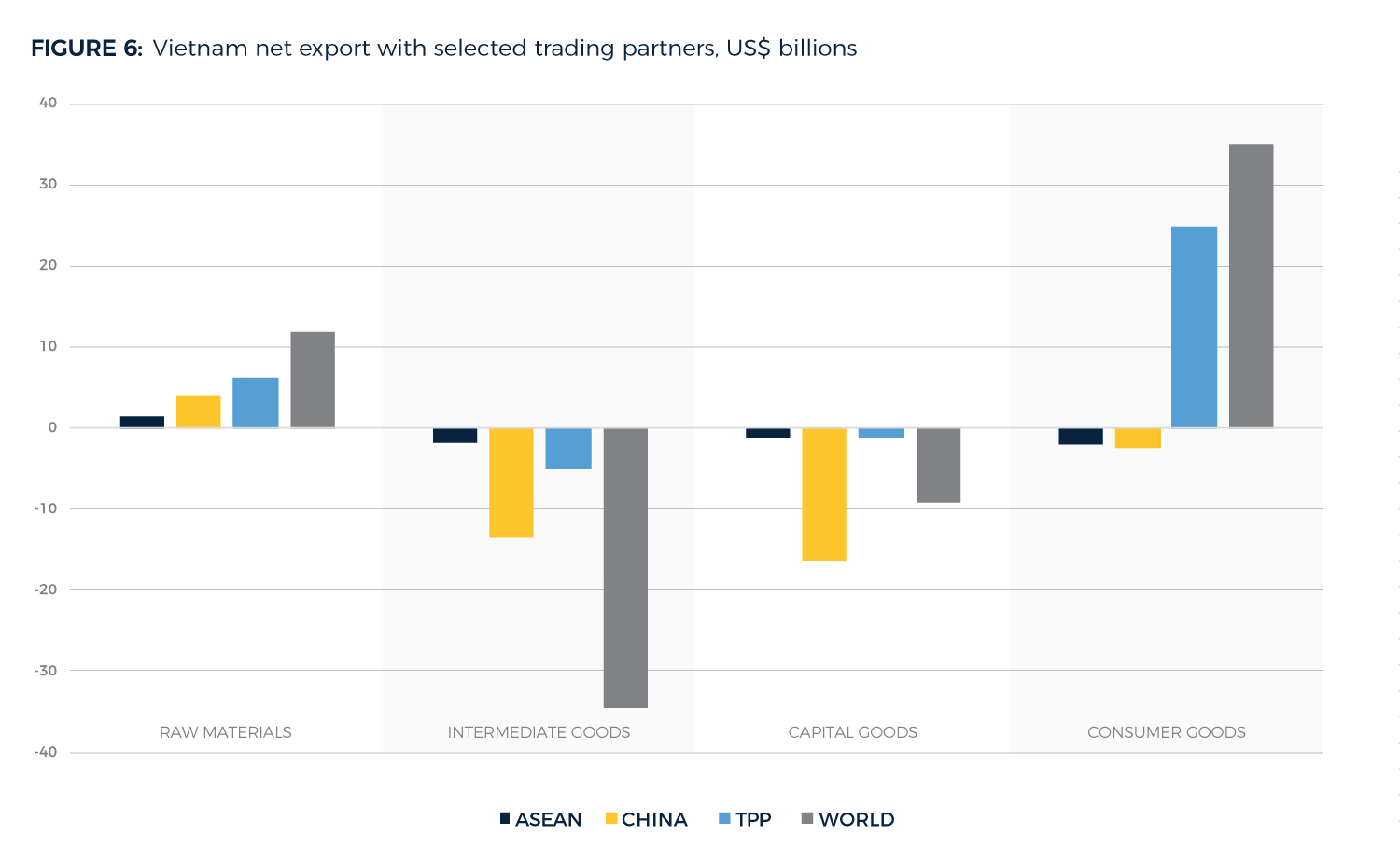

The garment and footwear sectors, the second- and third-largest export sectors, demonstrate how large exports and trade surpluses do not always mean commensurate levels of domestic value added.[64] On the contrary, value added domestically can be small when investments are highly integrated into global supply chains. In these sectors, much of the value added derives from Vietnam’s low labour costs.[65] Many inputs are imported, often across several steps of the value chain with intermediate inputs exported, processed abroad, and then reimported.[66] Vietnam runs a $32 billion trade surplus with the United States, but only an estimated 5–8 per cent of this accrues as value to Vietnam.[67] Personal electronics from major brands such as Samsung and Intel form a large share of bilateral trade, but the value of exports can be as low as 3 per cent of a product’s final value.[68] The corollary of surpluses with one country are even larger deficits with a third country (often China), as manufacturers must import inputs, capital, and even production lines.

Table 1: Vietnam’s trade with selected partners, 2014 (US$ billions)

Partner | Trade flow | Raw materials | Intermediate goods | Consumer goods | Capital goods | Total | % Share |

World | Export | 23.7 | 19.7 | 60.8 | 44.5 | 148.8 | 100 |

Import | 11.9 | 54.4 | 25.9 | 53.8 | 145.9 | 100 | |

Net Exports | 11.9 | –34.7 | 35.0 | –9.3 | 2.9 | ||

China | Export | 4.6 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 14.9 | 10.0 |

Import | 0.6 | 16.8 | 5.8 | 20.1 | 43.3 | 29.7 | |

Net Exports | 4.0 | –13.6 | –2.5 | –16.4 | –28.4 | ||

ASEAN | Export | 3.2 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 19.0 | 12.7 |

Import | 1.7 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 22.5 | 15.4 | |

Net Exports | 1.5 | –1.9 | –2.1 | –1.1 | –3.6 | ||

TPP | Export | 10.2 | 4.8 | 32.1 | 11.1 | 58.2 | 39.1 |

Import | 4.0 | 9.9 | 7.3 | 12.2 | 33.4 | 22.9 | |

Net Exports | 6.2 | –5.1 | 24.8 | –1.1 | 24.8 |

Source: Duong Nhu Hung and Tran Quang Dang, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Vietnam”, Asian Management Insights 3, Issue 1 (2016), https://cmp.smu.edu.sg/ami/article/20161101/trans-pacific-partnership-and-vietnam

There is a saying in Vietnam that SOEs are your son, FDI enterprises are your mistress’s son, and private enterprises are somebody else’s son. Few aphorisms better encapsulate the challenge of broadening the economy to address the missing middle. Too often, SMEs come a distant third behind SOEs and foreign investors.[69] More than 95 per cent of Vietnamese companies are small-scale, and they struggle with lack of access to credit and land, and are usually reliant on old, often second-hand technology.[70] Foreign investors often negotiate directly with local governments to obtain highly competitive terms related to taxation and access to land.[71] This makes it difficult for SMEs to compete, and a lack of domestic competitiveness over the past ten years means larger export-focused FDI enterprises have little incentive to build business links to these less competitive domestic firms.[72]

Addressing the missing middle is not as simple as empowering a downtrodden private sector. Vietnam has never had an influential domestic commercial class, and the implementation of selected market institutions has reflected the priorities of those within the state. Most crucially, over the past 15 years Vietnam’s private sector has struggled to compete as the economy has become more open internationally.[73] The lack of sufficient progress on tackling institutional and policy impediments, such as expanding financial inclusion or creating more effective land rights, has reinforced the trend. Vietnam’s various FTAs and international trade arrangements also make it difficult for the government to extend subsidies or special treatment to its SMEs, for example.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

For many supporters of economic renovation, the TPP was seen as an attractive tool as it promised to tackle some of Vietnam’s major economic problems.[74] This courting of external support demonstrates how economic openness and domestic reform have historically gone hand in hand. Joining the WTO not only meant tariff and services liberalisation, it also allowed policymakers to push through nearly a decade’s worth of new commerce and business regulations and policies. Not everyone in Vietnam feels that all of these changes were in the country’s best interests. Many, for example, point to evidence that domestic enterprises lacked the competitiveness to benefit from greater exposure to international economic forces.[75] Even knowing this, most would choose the path of openness because of the opportunity it provided for parallel restructuring and change.

For Vietnam, the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the TPP removed the most readily apparent benefit: preferential access for garments and textiles to the US market. This would have made Vietnam one of the TPP’s biggest winners of the trade deal. An estimate of its gains from prospective tariff elimination was 6.8 per cent of real GDP, versus 1.1 per cent under the TPP-11.[76] Without the United States, Vietnam’s exports seem likely to grow less rapidly: under one estimate, exports to TPP members would have grown by 12 per cent by 2035, versus 6.8 per cent under TPP-11.[77] Real GDP will still increase with TPP-11, but at a far more muted 0.5 per cent by 2035, versus 1.9 per cent initially. As a result, selling TPP-11 domestically will become more difficult. True to Vietnam’s track record, however, many TPP backers emphasised the agreement for disciplining policymakers and deflecting domestic opposition. Officials interviewed by the author spoke of the agreement’s inherent “attitude change” or “mindset”; another explained, “without TPP many promises will fall by the wayside”.[78]

Source: UN Comtrade, International Trade Statistics Database

Another potential benefit for Vietnam were the TPP’s proposed rules of origin. The rules would have provided preferential treatment for goods with inputs sourced from TPP countries (or within Vietnam). This would have helped bring in high levels of investment from suppliers seeking to take advantage of the new rules. As discussed above, efforts to limit structural supply chain breaks would help boost Vietnam’s domestic value added.[79] During 2014–16, an estimated US$5 billion of FDI from China flowed into the garment and textiles sector as suppliers positioned themselves to leverage gains from the TPP.[80] Once the TPP became uncertain, such investment quickly tailed off. Finally, the TPP would also require Vietnam, perhaps conveniently, to reduce its support to SOEs and introduce new public procurement practices. Other changes including those related to intellectual property were slated to be accompanied by US technical assistance for Vietnam.

Vietnam and Australia

Australia’s economic relationship with Vietnam is advancing, and the countries’ trading relationship is the fastest-growing among the larger ASEAN economies.[81] Two-way trade now exceeds A$10 billion. Vietnam is among the largest users of tariff preferences under the ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade Area, an indication of its increasing trade with Australia. Australian officials believe there are opportunities for Australian businesses to grow their market share in the agriculture, education, energy, financial services, and tourism sectors.[82]

According to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, there are more than 22 000 Vietnamese students in Australia, the fourth-largest group of foreign students.[83] RMIT University was the first foreign university to set up a campus in Vietnam, and a growing number of Australian universities have partnered with Vietnamese institutions to deliver degrees in Vietnam, offer student exchanges, or provide pathways to further study in Australia. Food is integral to Vietnamese local culture, and there is rapidly growing demand for high-end beef, wine, and dairy, with Australian produce enjoying strong in-market recognition among increasingly affluent consumers.[84] Strong expected growth in mini-markets and e-commerce should provide a special opportunity for exporters that adapt an innovative approach to packaging and portioning of premium products.[85]

There is also a considerable Vietnamese diaspora in Australia. According to the 2016 Census, nearly 230 000 people reported speaking Vietnamese at home, and of the 40 per cent of Australians born overseas, 3.6 per cent (the sixth-largest group) are Vietnamese. Long-held community disapproval of business or commercial ties to Vietnam within the diaspora — unsurprising given many Vietnamese–Australians emigrated as refugees — are beginning to fade among younger Vietnamese–Australians and with new generations of migrants.[86] As the Vietnamese Government actively attempts to tap overseas Vietnamese — the so-called ‘Viet Kieu’ — as a source of investment and human capital, Australia’s substantial Vietnamese population could contribute to a further expansion of ties.

Australia’s other priorities and relationships in the region also recommend an interest in Vietnam. Vietnam has natural affinities with Australia in the security sphere, from their independent foreign policies and emphasis of the ‘rules-based order’ to regional maritime security issues in the South China Sea. Both countries also have an established relationship with key economic and strategic player Japan, which has emerged as the new coordinator of efforts to revive the TPP-11 agreement. Vietnam and Australia concluded an Enhanced Comprehensive Partnership in 2015, and the bilateral relationship includes strong development, education and training, and defence ties.[87] Defence ties were established in 1998, with expanded bilateral dialogues and talks in recent years.[88] Several Australian warships have made port calls in Vietnam in the past two years, and Australia is providing assistance to Vietnam’s first UN peacekeeping deployment.

Conclusion

The results of Vietnam’s three decades of economic transition are impressive. A range of factors helped Vietnam to attract investment and boost exports, including: a competitive investment regime; trade liberalisation; engagement with the international economic system; political stability; and low labour costs. The path of economic restructuring has been pragmatic and omnivorous. Its economic planners avoided debates about capitalism and instead justified the introduction of markets as a way of encouraging greater production and trade.

Yet, while trade and foreign investment are indispensable features of Vietnam’s economic success, they have not automatically translated into the creation of a vibrant and competitive private sector. Boosting Vietnam’s private sector has foundered on the dominance of the country’s numerous SOEs, which under current policy settings continue to dominate market access, credit and investment, and control of physical assets.[89] Export-oriented foreign investment has been attracted by an open trade regime and stable investment framework, but this has also limited incentives to build linkages to local suppliers and service providers. Thus Vietnam’s share of impressive exports and some large trade surpluses is less than might be expected. The productivity and share of domestic value of Vietnamese firms has actually declined as its economic integration has increased. Addressing this is the primary economic challenge for Vietnamese policymakers today.

Vietnam’s experience also underscores the potential downside of trade and investment liberalisation without concomitant efforts to address domestic institutions and standards. Efforts must be made to ensure domestic players also capture a slice of the gains. Indeed, the TPP’s focus on quality institutions and standards made the agreement appealing to Vietnam, even despite the certain difficulty of complying with a host of commitments on labour, environmental protection, and SOEs. Vietnam has a history of leveraging engagement with the international economic system — including joining the WTO and signing major FTAs — to support difficult domestic restructuring. These have been more pretext than driving force; many in Vietnam would note that far more laws and regulations were passed than were technically required to meet its WTO commitments.[90]

Most importantly, at a time of rising global protectionism, Vietnam continues to look outward in a unique way. The CPTPP agreement, though not yet completed, is positive for both Vietnamese as well as Australian interests. Even without a favourable outcome among the remaining eleven TPP signatories, however, the Vietnamese system would be likely to push forward with creative and incremental ways of importing and cementing change. Vietnam regularly impresses with its resourcefulness on the world stage — illustrated by the successful visit of Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc to Washington, the first Southeast Asian leader to call on President Trump.[91] At times, Vietnam has paid a price for its engagement with the world economy, but few in Vietnam would advocate a different path.

Acknowledgements and disclaimers

Thank you to all of the experts and practitioners who met with me throughout the course of my research, both in Vietnam and Australia. I am especially appreciative to the Australian Embassy in Hanoi and the Australian Consulate-General in Ho Chi Minh City for assisting me with my research. Your assistance and networks were invaluable, as were the conversations I was fortunate to have with your knowledgeable and professional staff.

I am also grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. All mistakes in the text remain mine.

About the author

Matthew Busch is a Research Fellow in the East Asia Program at the Lowy Institute. Matthew’s research focuses on the intersection of politics and economics in the emerging economies of Southeast Asia, with particular focus on Indonesia and Vietnam. Matthew holds a Bachelor of Arts, cum laude, in Economics from Harvard College. He was also a recipient of the college’s prestigious Michael C Rockefeller Memorial Fellowship, with which he travelled to Indonesia for the first time in 2007. Matthew is currently undertaking PhD research at University of Melbourne Law School.

The Lowy Institute acknowledges the support of the Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet for Matthew’s position.

Notes

[1] Vietnam has a relatively young population, although it is projected to start ageing rapidly. Its income levels are near the bottom of what is considered middle income, and many of its citizens are entering the middle class for the first time. In terms of human capital, great progress has been made to promote education, especially in science and mathematics.

[2] Purchasing power parity method, current prices, international dollars per capita. Data from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook 2017, http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPPC@WEO/VNM.

[3] World Bank, “Merchandise Trade (% of GDP)”, current US dollars, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TG.VAL.TOTL.GD.ZS?locations=VN.

[4] World Bank data. Total trade is slightly higher at 185 per cent of GDP.

[5] Confidential interview with the author, Hanoi, June 2017.

[6] Vietnam’s participation in global value chains has supported the growth of domestic value added in key value chains: textiles and apparel (above15 per cent average growth in domestic value added); transport equipment, that is motorcycles and motorcycle parts (above 45 per cent), and electronics/information and communications technology equipment (above 20 per cent). See World Bank; Ministry of Planning and Investment of Vietnam, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy (Washington DC: World Bank, 2016), 149–153, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23724.

[7] Vietnam is often described as an ‘export platform’. By definition, export platforms engage ‘vertical FDI’ — that is, multinationals invest in new production countries to exploit efficiencies such as labour costs or free-trade areas. Exports are oriented towards a home or third market. ‘Horizontal FDI’, by contrast, involves investment to gain access to an attractive local market. See Thanh Tam Nguyen Huu, Med Kechidi and Alexandre Minda, “Location Factors of Export-platform Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence from Vietnam”, No 13-04, Documents de Recherche, Centre d’Études des Politiques Économiques (EPEE), Université d’Evry Val d’Essonne, https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eve:wpaper:13-04.

[8] See US Department of State, “Investment Climate Statements for 2017: Vietnam”, 2017, https://www.state.gov/e/eb/rls/othr/ics/investmentclimatestatements/index.htm?year=2017&dlid=269866#wrapper.

[9] Confidential interviews with business figures and analysts, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, May–June 2017.

[10] Year-to-date exports as at 15 August 2017. Other major exports include textiles and garments (12 per cent), computers and electronics and spare parts (11.7 per cent), and footwear (7 per cent). Data from Ministry of Finance of Vietnam, General Department of Customs, “Statistics of Main Exports by Fortnight First Half of August, 2017”, https://www.customs.gov.vn/Lists/EnglishStatisticsCalendars/Attachments/715/2017-T08K1-1X(EN-PR).pdf.

[11] Confidential interviews with analysts and economists, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, May–June 2017.

[12] See World Bank, “Vietnam Country Overview”, last updated 13 April 2017, http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), “About Viet Nam”, http://www.vn.undp.org/content/vietnam/en/home/countryinfo/. The World Bank and UNDP report Vietnam’s poverty rate as 13.5 per cent in 2014. The poverty line was updated when Vietnam reached middle-income status, and therefore poverty statistics are lumpy in the past decade. In 2013, on a new headcount baseline, the poverty rate was 9.8 per cent, down from 14.2 per cent in 2010, according to UNDP. See Ministry of Planning and Investment, “15 Years of Achieving the Viet Nam Millennium Development Goals”, UNDP Country Report, September 2015, 12, http://www.vn.undp.org/content/vietnam/en/home/library/mdg/country-report-mdg-2015.html.

[13] Ministry of Planning and Investment, “15 Years of Achieving the Viet Nam Millennium Development Goals”, 58.

[14] In 2015, for example, 15-year-old students in Vietnam were ranked 8 out of 69 for science literacy, registering a PISA score of 525 compared to the OECD average of 493. See OECD, “Viet Nam: Student Performance (PISA 2015)”, Education GPS, http://gpseducation.oecd.org/CountryProfile?primaryCountry=VNM&treshold=10&topic=PI. In the overall rankings, based on mathematics and science results, Vietnam was 12th, behind the Netherlands, Canada, and Poland, respectively. The United States ranked joint 28th. For more on Vietnam’s strategy for achieving such impressive PISA assessments, see also Andreas Schleicher, “Vietnam’s ‘Stunning’ Rise in School Standards”, BBC News, 17 June 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/business-33047924. Within Vietnam there is some scepticism about these flattering metrics, with some noting that years in school do not correlate with human capital gains in the same way it does in most other countries. See also Nguyen Dieu Tu Uyen, “In Vietnam, the Best Education Can Lead to Worse Job Prospects”, Bloomberg, 21 August 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-20/in-vietnam-the-best-education-can-lead-to-worse-job-prospects.

[15] Opinions differ on the correct terminology for Vietnam’s economy. Vietnam considers itself a ‘socialist-oriented market economy’. Important economic partners such as Australia and Japan recognise Vietnam as a market economy. The US Department of Commerce, however, classifies Vietnam as a non-market economy. Although WTO rules prohibit non-market economy designation, under the terms of its WTO ascension Vietnam agreed non-market status could be used against it until the end of 2018. Elements of the TPP were specifically developed to address Vietnam’s non-market status. See K William Watson, “How Will the TPP Impact Vietnam’s ‘Nonmarket Economy’ Status?”, CATO at Liberty, 31 March 2015, https://www.cato.org/blog/how-will-tpp-impact-vietnams-nonmarket-economy-designation.

[16] Although Vietnam has benefitted greatly from strong cooperation with international development organisations, they have also taken a decidedly selective approach, only implementing policies that suit the local political economy. Confidential interviews with the author, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, May–June 2017.

[17] In effect, this means the Communist Party has remained the sole — and largely opaque — forum for political competition in Vietnam.

[18] This informal economic activity was, unsurprisingly, more developed in the South. Collectivisation had been imposed in North Vietnam in the 1950s. After reunification it was introduced in the South with poor results, as farmers withheld production or simply refused to plant at all.

[19] After lacklustre results from the ‘district as fortress’ agro-industrial approach approved at the 4th Party Congress, local leaders turned to the market mechanisms underwriting fence breaking. Some ‘fence breaking’ activities began in secret among commune members and were later adopted once they proved more effective at raising productivity and income. See Martin Rama, “Making Difficult Choices: Vietnam in Transition”, Commission on Growth and Development Working Paper No 40 (Washington DC: World Bank, 2008), 13–15, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/270911468327590018/pdf/577390NWP0E0an10gcwp040bilingualweb.pdf. Foreign affairs also played a role in the newfound flexibility, as war with China, instability in Cambodia, and reduced Soviet assistance demanded fresh economic policies.

[20] A need for greater food production was also driven by the dwindling of Soviet food aid.

[21] See Ming Wan, The China Model and Global Political Economy: Comparison, Impact, and Interaction (New York: Routledge, 2014).

[22] This has also been described as the ‘marketisation’ of the state itself: see Jonathan Pincus, “Vietnam: Building Capacity in a Fragmented, Commercialized State”, unpublished paper, 7 September 2015, 10, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311231412_Building_Capacity_in_a_Fragmented_Commercialized_State. See also Rama, “Making Difficult Choices: Vietnam in Transition”, 17–19, for a discussion of the roles played by local officials, especially in the South, in fence breaking and the strategies employed to avoid confrontations and slowly persuade a sceptical party leadership of the merits of their approach.

[23] By 1995, for example, the 100 largest companies in fence breaking-epicentre Ho Chi Minh City were SOEs.

[24] Confidential interviews with the author, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, May–June 2017. See also Martin Gainsborough, “Privitisation as State Advance: Private Indirect Government in Vietnam”, New Political Economy 14, No 2 (2009), 257–274, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13563460902826013. Gainsborough also examines the ‘push’ factors (e.g. conditions in the state sector) and ‘pull’ factors (e.g. private sector requirements and changes brought on by Vietnam’s commitments) related to gradualist and incremental equitisation progress: Martin Gainsborough, Vietnam: Rethinking the State (London: Zed Books, 2010), 75–78.

[25] Pincus, “Vietnam: Building Capacity in a Fragmented, Commercialized State”, 11.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Beyond WTO ascension in 2007, Vietnam joined ASEAN in 1995, the ASEAN Free Trade Area and the Asia–Europe Meeting in 1996, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in 1998.

[28] See World Bank, “Exports of Goods and Services (% of GDP)”, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?locations=VN.

[29] This is evocative of ‘gai-atsu’ or ‘foreign pressure’ in Japan in the 1980s and early 1990s, which described a tactic to obviate domestic opposition to changes such as trade liberalisation. Instead of the result of its domestic political and power relations, change was cast as the product of Japan’s need to accommodate foreigners (especially the United States). See Flora Lewis, “The Great Game of Gia-atsu”, The New York Times, 1 May 1991, http://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/01/opinion/the-great-game-of-gai-atsu.html.

[30] See World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy, 17–19.

[31] The headline growth target in 2017 is 6.7 per cent, but thus far annualised growth is below this target.

[32] The World Health Organization projects the share of Vietnam’s population over the age of 60 will increase from 10 to 18 per cent between 2015 and 2030. The number of elderly will increase from 10 million in 2017 to 19 million and 28 million in 2030 and 2050, respectively. See United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “World Population Ageing”, 2015, 11, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Highlights.pdf; see also “Viet Nam Prepares to Support Aging Population”, Viet Nam News, 9 September 2017, http://vietnamnews.vn/society/health/393500/viet-nam-prepares-to-support-aging-population.html.

[33] Among the primary benefits of WTO ascension were the removal of EU and US quotas and the reduction of many tariff lines on garments and textiles, at that time Vietnam’s second-largest export after crude oil. See “Approval for Vietnam”, The Economist, 8 November 2006, http://www.economist.com/node/8133733.

[34] Vietnam was unusually exposed to the world economy just before the turbulence of the global financial crisis, but local enterprises also coped poorly with new foreign entrants in many sectors. See Central Institute for Economic Management, Comprehensive Evaluation of Vietnam’s Socio-Economic Performance Five Years After the Accession to the World Trade Organization (Hanoi: Finance Publishing House and CIEM, 2013), 43–46.

[35] See Suiwah Leung, “Banking and Financial Sector Reforms in Vietnam”, ASEAN Economic Bulletin 26, No 1 (2009), 44–57. This also contrasted with Vietnam’s experience during the 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis, when problem lending — again, to SOEs — was confined to a relatively more manageable group of state-owned commercial banks. See Suiwah Leung and Le Dang Doanh, “Vietnam”, in Ross McLeod and Ross Garnaut eds, East Asia in Crisis: From Being a Miracle to Needing One? (London; New York: Routledge, 1998).

[36] For details, see Suiwah Leung, “Bank Restructuring in Vietnam”, East Asia Forum, 7 April 2013, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2013/04/07/bank-restructuring-in-vietnam/.

[37] The Vietnamese Asset Management Company (VAMC) resembles the Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency (IBRA), the entity used during the Asian Financial Crisis to restructure bad loans and issue bonds to recapitalise ailing banks. VAMC differs because IBRA acquired loans at zero cost — meaning the state effectively wrote them off at the time of the bailout.

[38] Banks have also been permitted to swap their non-performing loans at market value for normal bonds, but this would mean effectively writing off the asset, as many loans would have an effective value of zero. See Suiwah Leung, “Don’t Bank on Vietnam’s Financial Reform”, East Asia Forum, 7 January 2016, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2016/01/07/dont-bank-on-vietnams-financial-reform/.

[39] The US$20 billion estimate for total bad debts is accepted among experts. See also “Vietnam Seeks New Tools to Beat Bad-debt Woes, Eyes China-style Market”, Reuters, 26 October 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/vietnam-banks/rpt-vietnam-seeks-new-tools-to-beat-bad-debt-woes-eyes-china-style-market-idUSL3N12O05320151025.

[40] Government frustration at high interest rates is another consequence of banks’ assumptions about their non-performing loans and a resulting reluctance to lend, especially to the real sector. Confidential interview with economist, Ho Chi Minh City, May 2017.

[41] World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy, 20. Others have claimed SOEs’ share of investment is even higher, at nearly 50 per cent. See, for example, Ian Coxhead, “Vietnam’s Zombie Companies Threaten Long-term Growth”, East Asia Forum, 6 July 2016, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2016/07/06/vietnams-zombie-companies-threaten-long-term-growth/.

[42] Total public sector employment, including civil servants, teachers and security forces, is estimated at 10 per cent of total jobs. Confidential interview with the author, Hanoi, June 2017.

[43] Job creation in the foreign-owned sector is also relatively limited, despite large exports and investment, at approximately 4 per cent (or less than 2.5 million workers).

[44] See also Pincus, “Vietnam: Building Capacity in a Fragmented, Commercialized State”, 12.

[45] According to financial sector players, Vietnam has an unusually large share of private wealth — as much as US$40 billion or nearly 20 per cent of GDP — held in non-financial assets outside its banks. Considering the modern monetary theory axiom that ‘loans create deposits’, it seems clear the banking sector does not yet serve the bulk of Vietnamese households and private enterprises.

[46] As with other economic levers, many zoning decisions and rules around the transfer of land use rights are devolved to provincial-level governments.

[47] See World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy, 24–25, 146–147.

[48] Confidential interviews with economists, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City,

May–June 2017.

[49] Losses at major SOEs (their presumed bad debts, largely guaranteed, are around 30 per cent of GDP) are also a large potential fiscal overhang. See Coxhead, “Vietnam’s Zombie Companies Threaten Long-term Growth”.

[50] See “Vietnam’s Public Debt Ceiling Set at 65 Per Cent of GDP for2016–2018”, Vietnamnet, 25 April 2017, http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/business/177203/vietnam-s-public-debt-ceiling-set-at-65--of-gdp-for-2016-2018.html. The central government debt ceiling is 54 per cent of GDP. Considering the size of the economy and reasonable growth assumptions, public spending can expand roughly US$8–9 billion per year. As at mid-2017, observers in Hanoi noted debate in the National Assembly, which imposed the ceiling, to allow disposal of collateral might help unwind the debt overhang without forcing the government to either write a blank cheque or impose the full weight of potential banking losses on the system.

[51] On the “scramble for cash” prompted by concerns about Vietnam’s debt profile and large share of short-term local securities, see Suiwah Leung, “Vietnam’s SOE Sale Gathers Pace”, East Asia Forum, 5 September 2017, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2017/09/05/vietnams-soe-sale-gathers-pace/.

[52] As at 2013, the most recent World Bank data available.

[53] See World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy, 220. Subnational governments — there are 63 provincial-level governments — account for more than 50 per cent of total public expenditures and more than 70 per cent of public investment (World Bank, Vietnam 2035, 59).

[54] For a discussion on how institutional fragmentation contributes to Vietnam’s low quality public investment, see World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy (ibid), especially Chapter 7.

[55] This is an understandable impact of the 70 per cent of public spending administered at the subnational level. Confidential interviews with the author, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, May–June 2017.

[56] According to the US State Department’s 2017 Investment Climate Statement, “Decentralization of licensing authority to provincial authorities has in some cases streamlined the licensing process and reduced processing times. It has also, however, given rise to considerable regional differences in procedures and interpretations of investment laws and regulations.” Major projects in certain sectors and with investment capital of more than US$233 million require approval from the Prime Minister and/or National Assembly. See US Department of State, “Investment Climate Statements for 2017: Vietnam”.

[57] See “Provincial Competitiveness Index” (PCI), a popular and widely referenced initiative of USAID and Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry: http://eng.pcivietnam.org/. According to the 2016 PCI, 90 per cent of foreign businesses obtained all documents necessary to operate within three months of applying.

[58] Across 63 provinces and municipalities Vietnam has 260 industrial parks, but average occupancies are under 50 per cent. Subnational governments still plan, however, to build 239 more industrial parks by 2020. See World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy, 351.

[59] An economist interviewed by the author contrasted Vietnam, which has replicated the Chinese approach of situating investment promotion and servicing at the provincial level, with the ‘one-stop’ model pursued by peers such as Indonesia and the Philippines. As a result, leaders’ political aspirations are tied directly to FDI, as attracting investment raises their profile. This stimulates robust competition among provinces — witness the Provincial Competitiveness Index — but also a race to the bottom. This has particular consequences for taxation, which aggressive provincial governments are often keen to trade away.

[60] See Rama, 18–19, for example, about the adaption of Le Duan’s ‘warfare theory’ of avoiding direct confrontation with US military forces to controlling information about fence breaking to sceptical party seniors.

[61] See Pincus, “Vietnam: Building Capacity in a Fragmented, Commercialized State”, 16–21, especially discussion of how “institutional fragmentation” among various subnational state agencies has manifested in the suboptimal development of an ineffective array of small ports in and around Ho Chi Minh City.

[62] Confidential interview with economist, Hanoi, June 2017.

[63] There was extra concern when GDP growth in the first quarter of 2017 reached 5.1 per cent — well short of the 6.7 per cent target. Exports have since accelerated and growth exceeded 7 per cent during the following two quarters, resulting in 6.4 per cent annualised growth from January to September 2017. See Nguyen Dieu Tu Uyen, “Vietnam’s Economic Growth Surges to above 7% as Exports Climb”, Bloomberg, 29 September 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-29/vietnam-s-economy-expands-at-faster-pace-in-third-quarter.

[64] Domestic value added compares the gross value of goods and services exports with the cost of producers’ intermediate consumption. See OECD Data, https://data.oecd.org/trade/domestic-value-added-in-gross-exports.htm. Depending on how countries derive their competitiveness, lower domestic value added is not necessarily problematic. For example, Singapore and Korea have lower domestic value added than Vietnam. Vietnam’s domestic value added, however, has declined steadily over the past decade.

[65] In 2017, Vietnam’s prime minister claimed that only 20 per cent of total costs for an athletic shoe accrue in the production phase. See Matthew Busch, “Vietnam Turns on Diplomatic Charm in Washington”, Nikkei Asian Review, 22 June 2017, https://asia.nikkei.com/Viewpoints/Matthew-Busch/Vietnam-turns-on-diplomatic-charm-in-Washington.

[66] Only 64 per cent of export value comes from domestic inputs, down from

79 per cent in 1996. See World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy, 149–153.

[67] Confidential interview with economist, Ho Chi Minh City, May 2017.

[68] Vietnam’s electronics sector also trails regional peers, with domestic value added share of gross electronics exports around 30 per cent. See World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy, 149–153.

[69] An ex-official interviewed by the author estimated that half of all assets remain in the hands of the state. As a result, the state dominates many sectors such as consumer goods that would be better left to the private sector. Many privatisations often involve the sale of a trivial 2–5 per cent stake. Confidential interview with the author, Hanoi, June 2017.

[70] According to one economist interviewed by the author in Ho Chi City in May 2017, 75 per cent of the domestic private sector’s (i.e. SME’s) technology is over 20 years old, and often second-hand from countries such as China. Widespread use of old technology is a consequence of crowding out by SOEs: see Diep Phan, Chang Lian and Ian Coxhead, “Will Killing Zombie Companies Injure Demand for Skills? Privatization, Technology Choice, and Skilled Labor Employment in a Transitional Economy”, unpublished paper, 8 July 2016, https://aae.wisc.edu/coxhead/papers/Phan-Chang-Coxhead-Abstract.pdf.

[71] This often exposes enterprises of all types to corruption. The 2016 PCI survey noted two-thirds of enterprises reported having to pay informal levies equivalent to 10 per cent of their revenues, with 25 per cent of FDI enterprises reporting having to pay bribes to acquire an investment licence. Nearly half of all FDI enterprises reported corruption as the biggest ‘doing business’ challenge.

[72] FDI enterprises also produce the bulk of exports, which several interviewees estimated at 65–70 per cent. According to the most recent (August 2017) Vietnam Customs data, FDI enterprises made 70 per cent of nearly US$124 billion in exports. See Ministry of Finance of Vietnam, General Department of Customs, “Statistics of Main Exports by Fortnight First Half of August, 2017”.

[73] See World Bank, Vietnam 2035: Toward Prosperity, Creativity, Equity, and Democracy, 20, Figures O.6 and O.7. The domestic private sector’s firm-level productivity, or revenue per unit asset, has fallen from approximately 2.0 in 2001 to little more than 0.5 in 2014. This level of productivity is essentially the same as state-owned firms’ productivity, which has been flat over the same period.

[74] This is not meant to imply that Vietnam was driven to implement change solely by its international agreements. On the contrary, the agreements were often used to discipline the domestic system to follow through on contested policies around which an adequate domestic political settlement did exist.

[75] One interviewee noted that GDP grew between 8 and 9 per cent annually prior to Vietnam’s WTO ascension, but only 6–7 per cent since. For critics, this showed Vietnam opened up too quickly and, in return for WTO membership, exposed itself to deep imbalances in the global economy. It is worth recalling how the effects of the Asian Financial Crisis, which occurred during 1997–98 when Vietnam was far less integrated into the world economy, did not arrive in Vietnam until four years later.

[76] Kenichi Kawasaki, “Emergent Uncertainty in Regional Integration: Economic Impacts of Alternative RTA Scenarios”, GRIPS Discussion Paper No 16-28, January 2017, http://aftinet.org.au/cms/sites/default/files/1709%20Japanese%20NTM%20paper.pdf. Vietnam’s non-tariff barrier removal gains are a little better, falling slightly from 10.9 per cent to 9.3 per cent of GDP under the simulation.

[77] See Carlo Dade et al, “The Art of the Trade Deal: Quantifying the Benefits of a TPP without the United States”, Canada West Foundation, June 2017, Figure 6, http://cwf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/TIC_ArtTradeDeal_TPP11_Report_JUNE2017.pdf. The United States stands to lose a great deal from its non-participation in the TPP, as Vietnam’s imports in 2035 under the original agreement would have expanded by 7.1 per cent, versus a mere 1.1 per cent under TPP-11.

[78] Interviews with past and current officials, Hanoi, June 2017.

[79] Confidential interview with economist, Hanoi, June 2017. For example, imported fibre could be spun into yarn that is then exported, woven and dyed abroad, and then reimported to be finished as apparel.

[80] Confidential interviews with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, May 2017. See also Dade, “The Art of the Trade Deal”, 21.

[81] See Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Vietnam Country Brief: Bilateral Relations”, last updated 9 March 2017, http://dfat.gov.au/geo/vietnam/pages/vietnam-country-brief.aspx.

[82] See, for example, Steve Ciobo, “Reforms Result in Remarkable Economic Growth in Vietnam”, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 3 March 2017, http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/trade-investment/business-envoy/Pages/march2017/reforms-result-in-remarkable-economic-growth-in-vietnam.aspx.

[83] Craig Chittick, “Ambassador’s Dispatch: Cutting-edge Vietnam”, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 3 March 2017, http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/trade-investment/business-envoy/Pages/march2017/ambassadors-dispatch-cutting-edge-vietnam.aspx.

[84] See, for example, data on Australian food and beverage exports to Vietnam via Australian Trade and Investment Commission, “Food and Beverage to Vietnam”, accessed 29 November 2017, https://www.austrade.gov.au/Australian/Export/Export-markets/Countries/Vietnam/Industries/food-and-beverage. Food safety has become a particularly pronounced issue in Vietnam in recent years, providing a particular opportunity for Australian products. See Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Enjoy the Taste of Australia in Vietnam”, Media Release, 12 April 2016, http://vietnam.embassy.gov.au/hnoi/MR160414.html.

[85] See Australian Trade Commission, “Vietnam — Food and Beverage Opportunities”, Webinar for Australian Exporters, 4 February 2016, accessed via https://www.austrade.gov.au%2FArticleDocuments%2F1418%2FTaste-of-Aust-in-Vietnam-2016-Webinar-Presentation.pdf.aspx&usg=AOvVaw1cPFTa0jjojQ9SW9zQ1PNR.

[86] See Danny Ben-Moshe and Joanne Pyke, “The Vietnamese Diaspora in Australia: Current and Potential Links with the Homeland”, Report of an Australian Research Council Linkage Project, August 2012, 60–61, https://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/629049/arc-vietnamese-diaspora.pdf; and Emma Connors, “Australia, Vietnam, the Diaspora and Generational Change”, The Interpreter, 16 May 2017, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/australia-vietnam-diaspora-and-generational-change.

[87] Official development assistance from Australia to Vietnam is forecast to exceed A$80 million in 2017–18, and 750 Australian students have studied in Vietnam under the New Colombo Plan. See Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Development Assistance in Vietnam”, http://dfat.gov.au/geo/vietnam/development-assistance/pages/development-assistance-in-vietnam.aspx; and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Vietnam Country Brief: Education and Training”, http://dfat.gov.au/geo/vietnam/pages/vietnam-country-brief.aspx.

[88] The annual Australia–Vietnam Defence Ministers’ Meeting began in 2013.

[89] See Pincus, “Vietnam: Building Capacity in a Fragmented, Commercialized State”, 20, for an example of how a lack of consolidation and productivity among manufacturers of pharmaceuticals is influenced by downstream distortions in favour of SOEs. Foreign pharmaceutical companies are prevented by law from doing distribution, and SOEs exist in every province to supply generics to individual hospitals, which do their own procurement. As a result of distortions downstream, small, otherwise inefficient producers of generics are able to survive in manufacturing, a sector that appears, on a prima facie basis, open and competitive.

[90] Interview with WTO Study Institute, Ho Chi Minh City, May 2017.

[91] For more on Vietnam’s efforts to coax effective outcomes from the visit and, most importantly, avoid a bust up after the Trump administration named Vietnam in a list of trade “cheaters” to be investigated for large surpluses, see Matthew Busch, “Vietnam Turns On Diplomatic Charm in Washington”, Nikkei Asian Review, 22 June 2017, https://asia.nikkei.com/Viewpoints/Matthew-Busch/Vietnam-turns-on-diplomatic-charm-in-Washington.