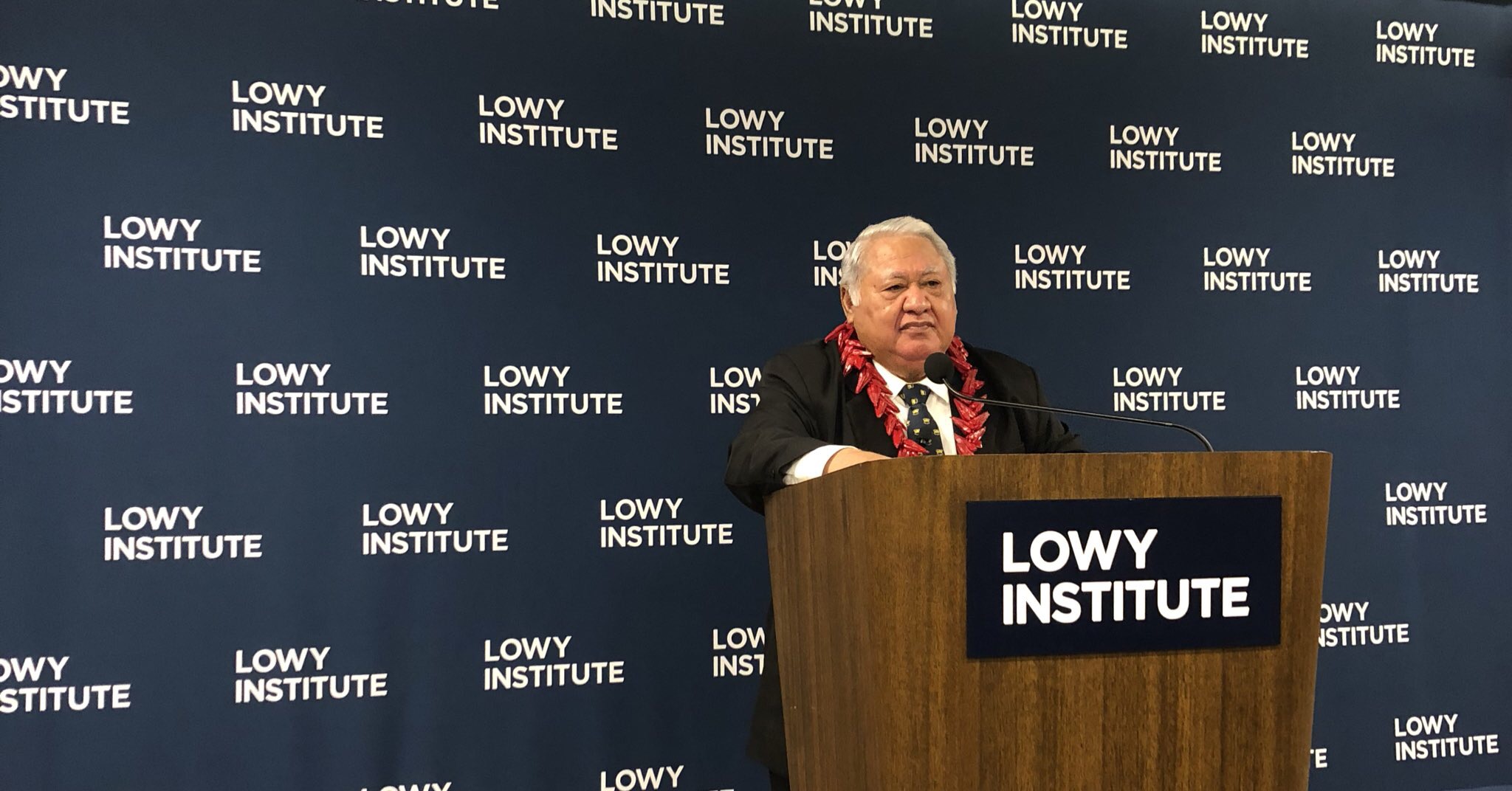

Speech by the Hon Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi on Pacific perspectives on the new geostrategic landscape

The Hon Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi, Prime Minister of Samoa, delivered this address at the Lowy Institute in Sydney on Thursday, 30 August 2018.

Check against delivery.

Chairman Sir Frank Lowy AC and Board, Executive Director Michael Fullilove, Experts and operations staff, Jonathan Pryke, Director of the Pacific Islands Program.

I thank you for the invitation to provide a Pacific perspective on the new geostrategic landscape. The hundreds of islands in the Pacific may appear only as small dots on world maps but, they are situated in a large strategic area.

For the Pacific, now is a time of profound change; and this change is occurring at an unprecedented pace. Geo-strategic competition between major world powers has once again made our region a place of renewed interest and strategic importance. Climate change and disaster risk affects our people in a variety of ways including increased severe weather events, scarcity of food and water, and displaced communities. Information and communication technologies (ICT) are burgeoning, and with them issues relating to accessibility, cyber security and cyber enabled crime.

While many countries are reshaping the global rules and institutions into ways that might not always support our interests or reflect our values, as Pacific countries, we remain resolute to assert such. What immediately comes to mind is the NZ Labour Government’s antinuclear policy in the eighties. It became a part of national and cultural identity and was an assertion of sovereignty and self-determination. An assertion that was taken up across the Pacific islands region and became a defining cause and concern for the South Pacific Forum — as the Pacific Islands Forum was then known.

The Pacific region is again seeking to assert its common values and concerns. Under the flagship of our Blue Pacific identity, we are building a collective voice amidst the geopolitical din on the existential threat of climate change that looms for all of our Pacific family. The Blue Pacific identity was endorsed by the Leaders of the Pacific Islands Forum when we met in Samoa last year. It represents our recognition that as a region, we are large, connected and strategically important. The Blue Pacific speaks to the collective potential or our shared stewardship of the Pacific Ocean. At this juncture we would like to note Australia’s longstanding membership of the Forum and endorsemet of the Blue Pacific identity as reaffirmed at the Forum Leaders meeting in 2017. We are also appreciative of the inclusion of a Pacific chapter in Australia’s White Paper.

As such all Pacific leaders are prepared to assert their common/shared interests namely security, prosperity, regional stability and constructive diplomacy and to be done in a way that elicits understanding and clarity of purpose. And we can do so without resorting to offensive and inflammatory remarks.

There is polarisation of the geopolitical environment. The concept of power and domination has engulfed the world; its tendrils extending to the most isolated atoll communities. The Pacific is swimming in a sea of so-called ‘fit for purpose’ strategies stretched from the tip of Africa, encompassing the Indian Ocean and morphing into the vast Blue Pacific ocean continent — that is our home and place.

And what is being asked of the inhabitants and longstanding stewards of the largest ocean continent on the Blue Planet? - to ensure freedom of navigation and open skies for strategic access. The precious resources and assets that we have, offer immense value and potential to the major powers of the world. At the same time these resources are the cause for panic especially for countries that have been given to believe “they are little and for too long classified ‘have nots’”. However, we are susceptible to being characterised as countries that have little, and that we should be grateful for whatever is offered to us.

I see us increasingly empowered to reject this characterisation. We are highly protective of our means of livelihoods, for example, embracing regional action to ensure the sustainability of our fisheries resources. And we are actively asserting our ambitions to ensure that there is inheritance for the generations to come.

But, we are also beset with dilemmas; as we seek to develop: do we give up our sovereignty, our uniqueness? An upgraded port, for example, may bring greater connectivity and opportunities for growth in some ways, but could it represent a ceding of sovereignty in other ways? There is a clear need to reinforce and support existing and promising approaches particularly those that are non-partisan and non-interventionist.

The reality is stark — we are again seeing invasion and interest in the form of strategic manipulation. The big powers are doggedly pursuing strategies to widen and extend their reach and inculcating a far reaching sense of insecurity. The renewed vigour with which a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy’ is being advocated and pursued leaves us with much uncertainty. For the Pacific there is a real risk of privileging Indo over the ‘Pacific’. There has been a reluctance to engage in open discussions on the issue and to share information to assist us in decision making.

Our Blue Pacific continent is becoming an increasingly contested space. The question for us is how prepared are we to tackle the emerging associated challenges? Regional and national stability has never been more critical in order to maintain peace and security, prosperity and wellbeing of all Pacific peoples and of peace.

At the very time the region has become a more crowded and contested strategic space. I get the sense that our traditional Forum partners left the neighbourhood, even if momentarily, and are coming back to claim a jurisdiction under their watch and to consider a re-energised Pacific strategy. Such an approach must be genuine and durable and premised on understanding, friendship, mutual benefit and a collective ambition to achieve sustainable results.

And in the process, our partners have fallen short of acknowledging the integrity of Pacific leadership and the responsibility they carry for every decision made in order to garner support for the sustainable development of their nations. Some might say that there is a ‘patronising’ nuance in believing that Pacific nations did not know what they were doing or were incapable of reaping the benefits of close relations with countries that are and will be in the region for some time to come. In cases where emerging partners have engaged with Pacific countries without conditionality, the relationships are perceived to be associated with corruption or unprecedented environmental degradation. One has the tendency to be bemused by the fact that the reaction is an attempt to hide what we see as strategic neglect.

The Framework for Pacific Regionalism identifies security as one of the four objectives of Pacific regionalism — “Security that ensures stable and safe human, environmental and political conditions for all”.[1]

While the Pacific region currently enjoys a period of relative stability, drivers of instability exist in the region and beyond. The 2017 State of Pacific Regionalism Report indicated that shifting global and regional geopolitics is creating an increasingly complex and crowded region that places the Pacific at the centre of contemporary global geopolitics. This trend, coupled with broader challenges such as climate change and disaster risk, rising inequality, resource depletion, maritime boundary disputes and advances in technology, will continue to shape the Pacific regional security environment.

Pacific Island Forum Members have a proud history of working collectively in response to events and issues that have challenged regional security, peace and stability, from the 1985 Rarotonga Treaty that created a nuclear free zone in the South Pacific, to a collective approach to addressing the existential threat of climate change.

The Pacific region’s current geopolitical and geostrategic context underlines the need for an integrated and comprehensive security architecture, incorporating an expanded concept of security. A stable and resilient security environment provides the platform for achieving the region’s sustainable development aspirations.

In recognition of this, in 2017, Forum Leaders “agreed to build on the Biketawa Declaration and other Forum security related declarations as a foundation for strategic future regional responses, recognising the importance of an expanded concept of security inclusive of human security, humanitarian assistance, prioritising environmental security, and regional cooperation in building resilience to disasters and climate change”.[2] Leaders have also prioritised action on climate change and disaster risk management, fisheries, and oceans management and conservation — all of which have significant security elements.

Thus, ‘Biketawa Plus’ is an outward looking declaration that acknowledges the changing geostrategic regional environment and commits members to work closer together to promote collective sovereignty (including through the ‘Blue Pacific’ narrative), to strengthen information sharing and to combat new and emerging security risks.

At their 46th Meeting in Port Moresby, Forum Leaders reiterated that climate change remains the single greatest threat to the livelihood, security and well-being of the peoples of the Pacific. While climate change may be considered a slow-onset threat by some, in our region its adverse impacts are already felt by our Pacific islands peoples and communities. Greater ambition is necessary to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees and Pacific island countries continue to urge and faster action by all countries.

The Blue Pacific narrative, which Forum Leaders endorsed in 2017, sees the region as a large oceanic continent, the ‘Blue Continent’. Pacific island countries manage 20% of the world’s ocean in their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). However, the ability to effectively secure the Blue Continent is constrained by its significant size, as well as the limited capacity and capability of countries’ border management systems. Maritime threats in the region encompass a broad range of issues from maritime boundary disputes, trafficking of drugs, wildlife and other contraband, human trafficking and people smuggling, arms smuggling, illegal fishing, accidents and disasters.

As Pacific leaders we strongly believe in being part of a Blue Pacific continent that is free from military competition, a Pacific that remains free from unrest and war that affect many other parts of the globe.

We welcome those that are committed to have honest conversations with Pacific leaders on good governance and transparency, open media, inclusive participation, domestic stability and developing resilience to enhance our economic prospects, and self reliance.

The Pacific has undertaken significant adaptation and mitigation strategies in response to climate change; the existential threat faced by some of our low lying atoll states are being faced now. Investment in climate resilience projects such as improving food and water security, climate proofing infrastructure and land reclamation for urban development, will help protect Pacific homelands and cultures, and also reduce migration challenges in the years to come.

Climate change is also increasing the frequency of destructive natural hazards, such as cyclones. In 2015, Forum Leaders’ endorsed the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific a global first for climate, disaster and low carbon development. We would welcome support to enhance resilience and preparedness particularly when we are experiencing disasters which can wipe 30 percent off a Pacific country’s GDP.

The recent disasters in the region have exposed the affected countries and communities to extreme economic, social and environmental impacts. While there is some financial products available for FICs to cope with the aftermath of natural disasters, there is very limited support for countries to build better and prepare to absorb the imminent threats from climate change and natural disasters. Global research shows that for every $1 spent on building resilience to catastrophic events saves up to $7 in response and recovery.

The Pacific Resilience Facility proposes to set-up a regional fund to assist Forum Island Countries’ government, private sector and communities to co-finance and leverage additional funding for resilience investment of new projects and/or retro-fitting existing infrastructure projects to make them risk resilient.

The strategic objectives of the proposed Pacific Resilience Facility are to strengthen the collective, cost-efficient and contextualised financial resilience by building strategic and genuine partnerships with key development partners and building national capacity development. It is important to note that the Pacific Resilience Facility addresses the current gaps in development financing and complements the existing initiatives in the region. We are very appreciatve of the Lowy Institute’s tool on Aid Mapping the Pacific which will inform decision making in the relevant areas of develoment cooperation in our respective countries.

In my view, the Blue Pacific platform offers all Pacific countries the adaptive capabilities to address a changing geostrategic landscape. The opportunity to realise the full benefits of the Blue Pacific rests in our ability to work and stand together as a political bloc. And the challenge for us is maintaining solidarity in the face of intense engagement of an ever growing number of partners in our region. We should not let that divide us!

In this regard we are looking forward to Australia’s stepped up engagement with the Pacific, including through: stronger partnerships for economic growth, for security and stronger relationships between our people,

Thank you.

[1] Framework for Pacific Regionalism, Forum Leaders’ Statement, 2014, 3, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-documents/pacific-robp-2015-2017-sd.pdf.

[2] Forum Communiqué, Forty-Eighth Pacific Islands Forum, Apia, Samoa, 5–8 September 2017, 6, https://cropict.usp.ac.fj/images/papers/ForumCommunique/2017-48th-Pacific-Islands-Forum-Communique.pdf.