Submission to the inquiry into the strategic effectiveness and outcomes of Australia’s aid program in the Indo-Pacific

Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

1. Introduction

I welcome the opportunity to make a submission to the Join Standing Committee’s review of Australia’s aid program. Over the past five years, through successive budget cuts, a hasty merger of AusAID into DFAT, and a consequent attrition of development professionals, the aid program has been left under considerable strain. Despite the best efforts of both diplomatic and development professionals a merger of cultures, objectives, personnel and resources of this magnitude has been very disruptive. To improve the strategic and development effectiveness of Australian aid more reasoned and well measured reforms are necessary.

Given the scope of this review, I have focused my submission on a few areas:

1. Objectives of Australian aid.

2. Australian aid governance within DFAT.

3. Modalities of Australian aid.

4. Australian aid transparency.

I have produced the following recommendations:

1. If the purpose of aid is to be reassessed, Australian national interest should be recognised as a driver, not just an outcome, of our aid expenditure.

2. An ‘Associate Secretary for Development’ should be created to sit between the Secretary and Deputy Secretary level and assume complete responsibility for development policy and aid management.

3. A development stream within the department should be created, starting from the graduate level, to professionalise development within the Department.

4. The Office of Development Effectiveness should have its mandate and resourcing expanded to include independent oversight of project design and implementation, as well as project evaluation.

5. The Office of Development Effectiveness should be tasked with carrying out a comprehensive assessment of the facilities model.

6. A specialised agency should be established to manage Australian concessional financing that is adequately staffed and resourced to identify a pipeline of bankable projects and leverage Australian private sector financing.

7. Transparency of Australian aid must be improved. Every aid project over $1,000,000 should have (through AidWorks) an automatically generated, publicly accessible, website.

2. The state of Australian aid

It has been a tumultuous decade for the Australian aid program. This decade has been categorised by three profound shifts: the size of Australia’s aid program, the governance of Australia’s aid program, and the vision for Australia’s aid program.

2.1. The size of Australia’s aid program

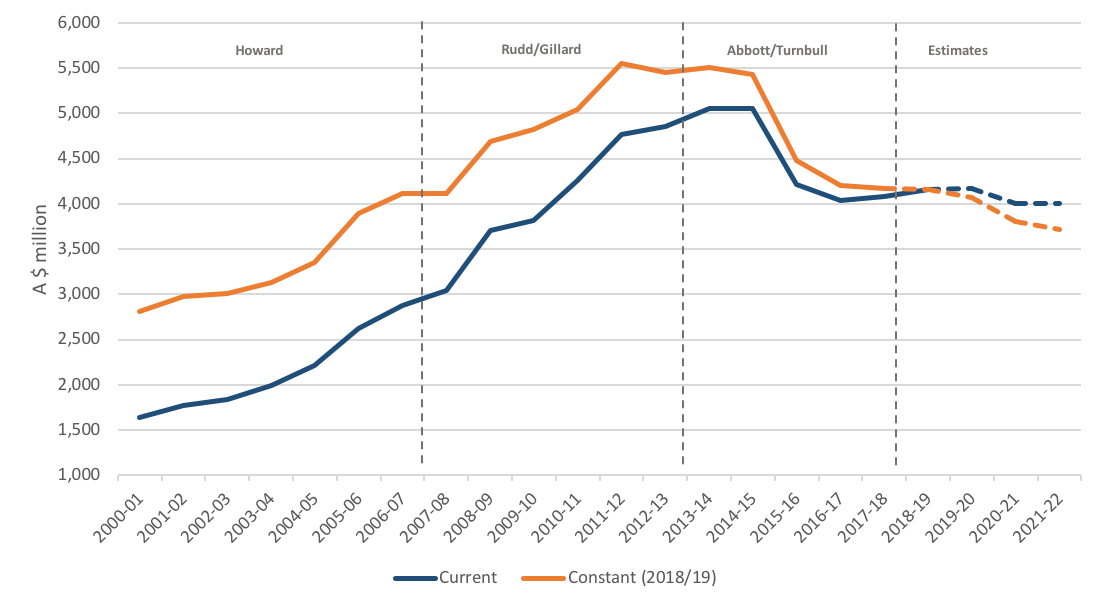

After an unprecedented scale-up of foreign aid under both the Howard and Rudd/Gillard governments, the Australian aid program has experienced a dramatic contraction under the Abbott/Turnbull government. Since its peak in 2013–14 at A$5.5 billion, the aid program has been cut by, in real (inflation adjusted) terms, 23.7%. Should the current trend continue, again when adjusting for inflation, by the end of the forward estimates period the aid program will be 32% smaller than at its peak.

Figure 1: Volume of Australian aid over time

Source: Development Policy Centre Aid Tracker

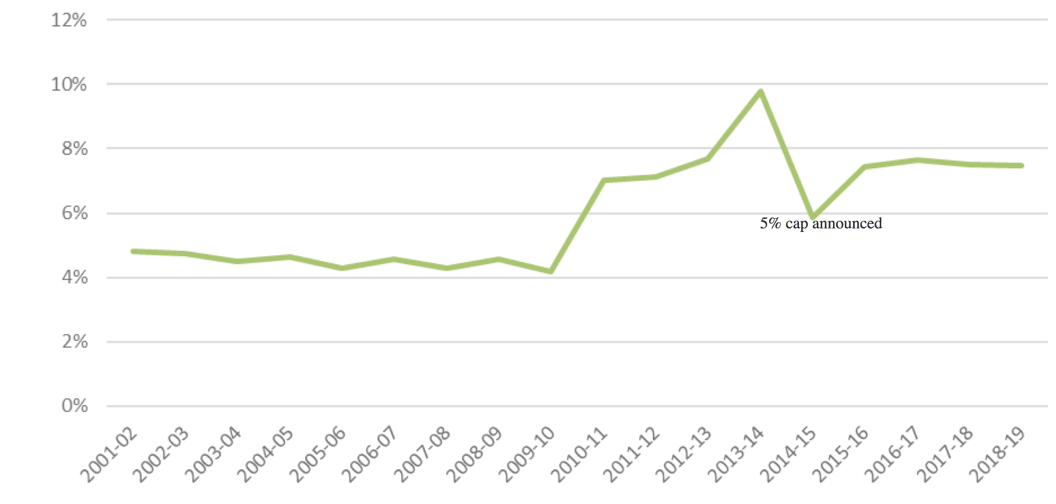

The results of these cuts have left the Australian aid program the least generous it has been in Australia’s history, reflected in figure 2. The international bench-line measurement for aid generosity is taken as aid as a proportion of Gross National Income. This allows donors with economies of different sizes to compare their aid efforts. The UN mandated objective is to reach an aid to GNI ratio of 0.7%. In the 2007 election there was bipartisan support for Australia to reach 0.5%. On current trends, Australia is on track to reach 0.19% by the end of the forward estimates period, from a peak of 0.34% in 2013/14.

Figure 2: Australian aid generosity over time

Source: Development Policy Centre Aid Tracker

By 2020 this will place Australia in the bottom third of OECD nations. Despite the uninterrupted economic growth that Australia has enjoyed over the past 27 years, by 2021 our donor peers in terms of generosity will be Spain, the United States, Portugal, Slovenia, Greece, Korea, Czech Republic, Poland, Slovak Republic and Hungary. The UK, despite being hampered by severe austerity, recently achieved the UN mandated 0.7% aid/GNI target. Australia has not faced similar austerity, with government expenditure by the end of the forward estimates period increasing in real terms by 12.6% since the 2013–14 budget. Aid as a proportion of overall government expenditure will also reduce from 1.24% in 2013–14 to 0.74% by the end of the forward estimates period.

By every measure, domestically and internationally, Australian aid volumes are going backwards.

2.2. Governance of Australian aid

In 2013 the Australian aid program also underwent the most dramatic overhaul in the way in which it is managed in the past forty years. Soon after taking power Prime Minister Tony Abbott made the surprising announcement that Australia’s agency responsible for aid management for the past forty years, AusAID, would be merged back into DFAT.

The merger took place at a stunning pace, with little or no blueprint or strategy for retaining highly qualified staff, no identification of how cultures of two very different organisations would be integrated, nor how aid management would be integrated into the department.

At the time of the merger DFAT maintained a staffing base of 2,521 Australian staff plus another 1,771 locally engaged staff, a total of 4,292 staff. AusAID had 1,724 staff, plus 651 locally engaged staff, a total of 2,375. AusAID also maintained an operating budget twice the size of DFAT’s. By mid-2015 DFAT cut its staffing complement by about 500 positions, on top of around 280 that had already departed in the month’s following the mergers first announcement, most of which came from former AusAID staff. At best estimate, 13 of the 16 Senior Executive Service officers within AusAID left at the time of the merger or shortly afterwards.

Following this dramatic shift in aid governance structures, aid management has been greatly decentralised out to country missions. The program relies more heavily on private contractors to provide services that were once managed internally within AusAID, namely project design, oversight and review. Many diplomats without any development experience have been placed in positions with oversight of significant sums of Australian taxpayer funds. AusAID staff have similarly been placed in diplomatic positions with job descriptions very different from their previous roles.

The merger of the Australian aid program into DFAT remains incomplete, but even so it is clear that the merger has come at the cost of the aid program’s effectiveness. The deep integration of aid responsibility into the DFAT structure has resulted in diffuse overall responsibility for the aid program. Four of the five DFAT divisions now house some degree of aid responsibility. This is explored in more detail in section 4.

While the aid program has suffered an overall loss of profile as a result of the DFAT merger, it has been politically elevated under this government with the creation of a Ministerial position for International Development and the Pacific. This should be applauded and maintained. One of the weaknesses of Australian aid is that it has a marginal supporter base in Australia, as I have discussed elsewhere. Increasing political responsibility for the aid program can help to redress that.

2.3. New strategic direction for Australian aid

In addition to the dramatic cuts to the aid program and the merger of AusAID into DFAT, Foreign Minister Bishop announced on July 9 2014 a ‘new aid paradigm’ that would refocus the vision and objectives of the Australian aid program. With a renewed focus on “aid-for-trade” and economic development, the government made a clear commitment to move away from the traditional service delivery sectors of education and health. The government also committed, rightly, to refocusing aid efforts to the Indo-Pacific region, resulting in a major drawdown of bilateral aid programs in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. While experts at the time argued that the new aid paradigm was more rhetoric than reality, there has been a significant geographic and sectoral rebalancing since 2013–14.

Table 1: Geographic rebalancing

|

2013–14 (thousands) |

2013–14 (share) |

2018–19 (thousands) |

% share |

|

|

PNG and Pacific |

1,068,691 |

21% |

1,283,600 |

31% |

|

East Asia |

1,302,936 |

26% |

1,027,200 |

25% |

|

South West Asia |

432,444 |

9% |

284,800 |

7% |

|

Other Asia |

43,017 |

1% |

(N/A) |

0% |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

263,835 |

5% |

121,100 |

3% |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

133,240 |

3% |

137,400 |

3% |

|

Other Africa |

9,904 |

0% |

(N/A) |

0% |

|

Latin America and Carribean |

26,516 |

1% |

5,900 |

0% |

|

Rest of World |

1,755,146 |

35% |

1,301,200 |

31% |

|

Total |

5,035,729 |

4,161,200 |

Source: Australian aid statistical summaries, DFAT

Table 2: Rebalancing of ‘investment priorities’

|

2013–14 (thousands) |

2013–14 (% share) |

2018–19 (thousands) |

2018–19 (% share) |

|

|

Infrastructure, trade and international competitiveness |

502,701 |

10% |

768,800 |

18% |

|

Agriculture, fisheries and water |

323,031 |

6% |

378,900 |

9% |

|

Effective governance |

850,472 |

17% |

811,800 |

20% |

|

Education |

1,008,002 |

20% |

637,200 |

15% |

|

Health |

755,579 |

15% |

435,700 |

10% |

|

Building resilience |

962,938 |

19% |

690,900 |

17% |

|

General development support |

648,811 |

13% |

437,700 |

11% |

|

Total |

5,051,533 |

100% |

4,161,000 |

100% |

Source: Australian aid statistical summaries, DFAT

Given the significant cuts to the aid program over this period, the changing proportions underrepresent how large these shifts have been. For example, while Education has shifted as a proportion of the aid program’s focus from 20% to 15%, in nominal terms is has actually decreased by $371 million, or more than a third.

This strategic and geographic realignment is to be expected with any change of government, but on top of the sweeping shifts in the way aid is managed by Australia, and the significant cuts, it has resulted in a difficult five years for the Australian aid program.

3. Objective of Australian aid

A question that has been vigorously debated over the history of Australian aid, both when scaling up and when drawing down, is why Australia gives foreign aid. In 2012 the Lowy Institute Interpreter ran a debate series on the question. It has also been discussed in numerous foreign aid reviews, and in detail by Stephen Howes of ANU’s Development Policy Centre in 2013. What has been clear from this debate is that there is a constant struggle between the dual objectives of the aid program meeting both humanitarian and national interest goals.

The most recent articulation of the overall objective of Australian aid comes from the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper (where aid received little overall attention), which states:

“Australia’s development assistance is focused on the Indo–Pacific and promotes the national interest by contributing to sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction.”

This is nearly identical to the objective detailed by the government when AusAID was merged into DFAT:

“Australia’s aid program will promote Australia’s national interests through contributing to international economic growth and poverty reduction.”

This, in turn, is very close to the Howard/Downer justification for aid in 1996:

“Advancing Australia’s national interest by assisting developing countries to reduce poverty and achieve sustainable development.”

By 2006 the Howard/Downer government had softened their tone on the national interest, shifting the objective to:

“To assist developing countries to reduce poverty and achieve sustainable development in line with Australia’s national interest.”

The Rudd/Smith government, and later Gillard/Rudd government, following the 2011 Independent Review of Aid Effectiveness, defined the objective of Australian aid in the following terms:

“The fundamental purpose of Australian aid is to help people overcome poverty. This also serves Australia’s national interests by promoting stability and prosperity both in our region and beyond. We focus our effort in areas where Australia can make a difference and where our resources can most effectively and efficiently be deployed.”

These justifications for aid have never adequately framed why aid is in our national interest. It should be acknowledged that the national interest is not just an outcome of our foreign aid program, but it directly shapes the aid program in many ways. Since the 1950s our geography dictated that aid is not only a good thing for Australia to do but is also in our geostrategic and commercial interest. There are many reasons why our aid program is good for the Australian national interest. It builds goodwill and strong institutional linkages with our immediate neighbours. It is in our commercial interest to help promote the economic growth of the countries around us. And, most critically, it also helps improve people’s lives. Aid investments are made with a consideration of all of these factors.

Our aid program has never been, and will never be, allocated along purely development or performance lines, and we should stop pretending so. There is a litany of examples here — investments in the Kokoda track, TB prevention at the Torres Strait, doubling our aid program to Cambodia, investments on Manus island, and most recently the undersea cable to Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. At the macro and country level, national interest contributes far more to aid investment decisions than development priorities.

Ultimately the way in which the aid program is administered day-to-day, and the way investment decisions are made at the country level, are not affected by the overall stated objective of Australian aid. It matters little for aid implementation. But the articulation of the objective of our aid program remains important to justify its expense both in political circles and with the general public.

If we are to readdress the objectives of Australian aid, equal weight should be given to serving Australia’s national interest both in the way in which aid is given, as well as the outcomes it promotes. For example:

“The objective of Australian aid is to promote sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction. Australian aid is focused on areas that support our strategic and national interest.”

Recommendation 1: If the purpose of aid is to be reassessed, Australian national interest should be recognised as a driver, not just an outcome, of our aid expenditure.

By better enshrining national interest as a key driver of Australian aid, alongside economic growth and poverty reduction, the aid program could become more impervious to future cuts, and could build a greater constituency of support with the Australian public and Parliament.

4. Aid governance within DFAT

The aid program has always laboured under multiple and competing objectives, both implicit and explicit. This was identified in the 1997 Simons Report on foreign aid, commissioned by the Howard Government. Paul Simons, then chairman of Woolworths and head of the review, noted that:

“The managers of the aid program struggle to satisfy multiple objectives driven by a combination of humanitarian, foreign policy and commercial interests. The intrusion of short-term commercial and foreign policy imperatives has hampered AusAID's capability to be an effective development agency.”

As the aid program matured and grew in the 21st century, it appears that this trade-off became less pronounced, with the 2011 Independent Review of Aid Effectiveness making little mention of it, though acknowledging national interest as a key driver of investment decisions, as discussed above.

The complete integration of the Australian aid program into our diplomatic and trade service has resulted in a situation far more challenging than experienced by aid management predecessors. The challenge of balancing diplomatic, trade and development priorities and expectations, which in many cases may counter each other, is acute. This runs the risk of making our aid program more transactional, which in turn can blunt the effectiveness of our aid over the long-run.

There have been some positive signs of the continuing professionalisation of the aid program within DFAT. The ‘Blue Book’ (now orange), often referred to as the Australian aid bible, returned after a brief hiatus and continues to expand in detail. Statistical summaries of aid expenditure are again being produced. DFAT continues to produce an annual performance summary of Australian aid. The Office of Development Effectiveness, a legacy of AusAID to survive the merger, continues to produce good assessments of individual projects.

There have been other benefits to the merger. There is significantly enhanced policy alignment between our development and diplomatic efforts, which is critical especially within our immediate neighbourhoods of the Pacific and Southeast Asia where aid is a major vehicle for broad institutional engagement. Development capacity has also helped fill some of the ‘diplomacy deficit’ that DFAT has experienced over the past decade, with many development professionals now acting in ‘blended’ roles. The aid program should now also benefit from a higher profile within foreign policy decision-making, even though this was not reflected in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper.

Despite these benefits, more is needed to both re-professionalise our aid program, from project design through to implementation and monitoring and evaluation, as well as streamline the responsibility of aid management to make individuals more accountable for performance.

4.1. Streamlining responsibility for development

The current approach of the merger has been one of near complete integration. DFAT is structured into five Groups, serviced by 36 Divisions and 85 branches (ten of which sit outside of the five Groups). Of these 85 branches, more than half have some degree of aid responsibility. These branches are spread across four of the five DFAT Groups. Four Divisions that focus exclusively on aid — Contracting & Aid Management; Humanitarian, NGOs & Partnerships; Development Policy; and Multilateral Development & Finance — are housed within three separate Groups. Meanwhile, responsibility for most bilateral programs sits under a fourth Division, the Indo-Pacific Group, which is in turn largely devolved to Embassies and High Commissions.

This degree of integration has been detrimental to the aid program. Responsibility for overall aid management and performance is too diffuse. Aid also receives too little profile at the upper levels of management within DFAT. In the past, a critical issue for the aid program was a lack of political responsibility to match its bureaucratic clout and cost to the taxpayer. We are now experiencing the inverse. We have a dedicated Minister responsible for aid and the Pacific, but no streamlined or concentrated responsibility for aid effectiveness at the top of the bureaucracy in DFAT.

This has a negative impact on the long-term effectiveness of our aid. Aid is becoming more transactional, in large and small ways. The rapid decline of investment in long-term scholarships in favour of short-term study tours has been put forward as one example, which is certainly not in our long-term interest. The Coral Sea Cable between Australia, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands is another high-profile example. This project is an ideal case for concessional finance, but instead has been funded by grant aid (more on this in section 5). Management of bilateral programs by in-country missions also favours short-termism with DFAT staff, despite best intentions, often working to solve problems of the day, and losing focus on the long-term strategic objectives of aid projects.

One approach to streamlining responsibility for development is to isolate the many divisions that have a majority focus on the aid program (including budgeting) and place them in a new Group, helmed by a Deputy Secretary who has final responsibility for the aid program. This would essentially create an aid policy, design and management division within DFAT.

However, the Department has already spent a significant amount of time and resources integrating the aid program and restructuring the entire bureaucracy. There is little appetite to implement more significant restructuring, and it would take up time and valuable human resources. There is also synergy in some areas of integration, particularly within the bilateral branches where aid can make up such a critical component of the government’s relationship.

Another, less disruptive, option would be to create a new senior position within the DFAT bureaucracy that sits in between the Secretary and Deputy Secretary level and has overall responsibility for aid policy. This Associate Secretary would have final responsibility for development policy and aid management, and would report only to the Secretary, the Minister for International Development and the Pacific, and the Foreign Minister. This would still be a slightly untidy option but would maintain the degree of integration DFAT has aspired for with the aid program over the past five years.

Recommendation 2: An ‘Associate Secretary for Development’ should be created to sit between the Secretary and Deputy Secretary level and assume complete responsibility for development policy and aid management.

4.2. Professionalising development

Creating a high-profile position within DFAT with sole responsibility for the aid program is only half the challenge. Another is making DFAT an appealing place to have a fulfilling career as a development professional.

As detailed above, at the time of the merger there was a significant attrition of development professionals from the aid program. Some of this was natural, as AusAID had based staffing assumptions on an increase of aid volumes to $8 billion by 2020. The haste at which the merger took place meant that there was no capacity review to ensure critical development staff were retained.

This decline in development capacity was apparent in the 2015 Australian aid stakeholder survey, where three quarters of respondents viewed staff expertise as a ‘weakness’ or a ‘great weakness’ of the aid program, up from half in 2013. I would expect the response to be similar when the survey is carried out again this year.

Figure 3: AusAID/DFAT administration to ODA ratio

Source: Stephen Howes, 2018 Aid Budget breakfast presentation, Development Policy Centre

Despite this apparent decline in development capacity, the administration-to-ODA ratio remains surprisingly sticky, hovering at around 7.5%. This is likely due to the adoption of more ‘blended roles’ helping to fill the diplomatic deficit discussed above. Unfortunately, these generalist roles come at the cost of specialist skills. There are critical elements of aid management that require skillsets developed over time and experience such as contracting, budget and stakeholder management, project management, monitoring and evaluation, development economics, development policy, aid program design, sectoral skills, and so on.

The Department has recently completed an internal capability assessment for aid management, which should be fully implemented. But the Department should go even further in creating a specialised development stream within the bureaucracy, starting at the graduate level. As it stands there is no graduate pathway for development specialists, and the department heavily favours recruitment and promotion from within.

An alternative to creating a standalone stream for development is to train the entire next generation of Australian diplomats in the basics of aid design and management. This could be done through extending the graduate program from two to three years, and making aid management, either at post or in Canberra, a mandatory component at some stage of every diplomatic career. This seems a more arbitrary approach, as there are no doubt diplomats that are unenthused by aid management, and vice versa.

There are still a great many competent aid professionals scattered around the department, but there is no formal structure to enable them to establish and develop specialist skills in the development space while also rising through the ranks of the bureaucracy.

Recommendation 3: A development stream within the department should be created, starting from the graduate level, to professionalise development within the Department.

Creating a visible and powerful position at the top of the bureaucracy to be the custodian of the aid program, combined with establishing a pipeline of development professionals from the bottom of the bureaucracy, will help DFAT better manage our aid program now and in the future.

5. Modalities of aid

Observations in this section are largely drawn from experience in the Pacific Islands region. While the Pacific does now make up a third of the aid program and half of bilateral aid expenditure, implementation of aid as well as aid performance varies across regions facing acutely different development challenges.

5.1. The role of the private sector

The role of the private sector in development has been hotly contested since the private sector first became engaged in development. In recent years in Australia the situation has become particularly acute, with revelations that just ten companies now manage close to 20% of the aid budget. The development NGO community, as illustrated in the submissions to this inquiry that have already been released, are quick to criticise.

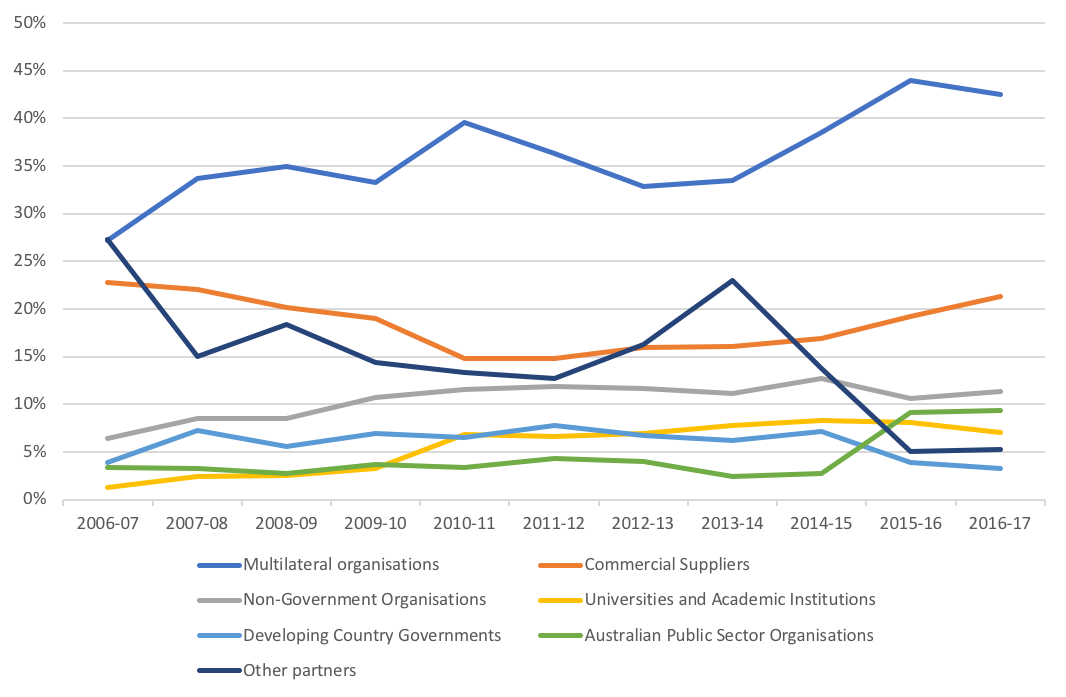

Source: Australian aid statistical summaries, DFAT

Figure 4 illustrates, however, that even though aid delivered through commercial suppliers has been increasing since the merger, it was still 2% higher as a proportion of total aid expenditure in 2006–07. Over that period aid implemented by the private sector has increased, in nominal terms, from $655 million to $858 million, but overall aid has increased from $2.88 billion to $4.03 billion. The reality is that the private sector has had, and will continue to play, a crucial role in development. The Australian government should remain agnostic when it comes to modalities of aid delivery for any given aid project.

It should, however, be careful about the ways in which it engages the private sector, and what for. As capacity has thinned out within DFAT there has been a growing tendency to engage the private sector to handle more of the burden of project design, project review, and in some instances independent project oversight. The most recent case of this was the publicly tendered $3.7 million over three years PNG Quality and Technical Assurance Group, a project designed to contract a private sector party to provide oversight over two private sector facilities, The Justice Services and Stability for Development and the PNG Governance Facility. This project is no doubt born out of a necessity for these large projects demanding a larger degree of oversight than DFAT had the internal capacity to manage (especially given the already high administrative ratio already outlined). But there must be a better way than having the aid program pay a private sector company to provide independent oversight over another private sector company implementing an aid program.

The Australian aid program has always relied on the private sector and consultants to varying degrees to supplement and provide as-needed independent reviews and assistance on project design. However, the volume at which this is happening under DFAT needs to be reviewed, and the department’s in-house capacity needs to be rebuilt so that the it does not run the risk of outsourcing its brain.

Recommendation 4: The Office of Development effectiveness should have its mandate and resourcing expanded to include independent oversight of project design and implementation, as well as project evaluation.

5.2. Sector-wide aid facilities

In late November 2017, Jacqui de Lacy, a widely respected aid professional formerly of AusAID/DFAT and now of Abt JTA Associates, wrote a persuasive piece for Devpolicy defending the role of facilities in development. Facilities, in essence, are private sector managed programs that take responsibility for all development activities in a particular sector in a recipient country. Facilities are justified on the terms of value for money (one overhead instead of many), efficiency (reducing demands on Embassy/High Commission time), and greater flexibility/responsiveness.

Facilities are nothing new for the aid program. Sector-wide programs were implemented in the days of AusAID, and mature sector-wide programs are now in the 3rd or even 4th phases. There are currently around 20 active facilities in the Pacific Islands region alone, accounting for more than $1.5 billion in aid commitments over a 10-year period. Jacqui de Lacy pegged the figure at anywhere between 8 and 35% of the bilateral aid program as now being managed under a facility model. The appetite for facilities under DFAT continues to grow and larger facilities have emerged in recent years.

As more of the bilateral aid program is channelled into larger facilities, there are mounting concerns that the rationale behind the facilities approach may not be transferring into practice. There is a clear efficiency dividend in the facility model, but it also puts more of our eggs into one basket, thereby enhancing implementation and performance risk. The larger the facility gets, the greater the risk that they become ‘too big to fail’. And the larger the contracts become, fewer firms have the capacity to bid on or manage them. There is also a rationale that facilities can help free up DFAT staff to focus on strategy, relationship and performance. This only works if DFAT staff can appropriately distance themselves from the day-to-day micro-management of a facility, which may often not be the case in practice. Facilities can also potentially reduce the burden on partner governments by only having to coordinate with one project. Again, this is dependent on facilities being given the latitude necessary to engage directly with government, which may not be the case in all instances.

The performance of facilities is also varied. A recent independent review of the PNG Transport Sector Support Program, one of the largest facilities, showed it to be working quite well. The Australian government should not take a dogmatic role on facilities. They have been a component of the aid program for some time. If we are to continue to invest in a smaller number of larger aid projects, however, we have to have a better understanding of when they work and why.

Recommendation 5: The Office of Development Effectiveness should be tasked with carrying out a comprehensive assessment of the facilities model.

5.3. Creating an Australian aid lending arm

In the last few months there appears to be growing bipartisan support for the Australian aid program to become more engaged in directly financing infrastructure projects in our immediate region, especially the Pacific. The Australian government recently announced the contracting of the much discussed $136.6 million Coral Sea Cable grant project between Australia, PNG and the Solomon Islands. Shadow Foreign Minister Penny Wong also made a recent call for Australia to enhance its infrastructure spend in the region.

If Australia does want to take infrastructure investment seriously then it should strongly consider establishing a concessional financing arm of the aid program. Concessional lending is defined by the OECD as follows:

“These are loans that are extended on terms substantially more generous than market loans. The concessionality is achieved either through interest rates below those available on the market or by grace periods, or a combination of these. Concessional loans typically have long grace periods.”

Only a proportion of these loans can be classified as ODA — the amount deemed ‘concessional’. Because they are paid back over time, they count as negative ODA flows. Concessional loans have a number of advantages. Developing countries face significant public infrastructure deficits that require financing. Concessional loans can offer benefits to donors in terms of recycling finance and leveraging additional finance. Core contributions to multilateral agency lending activities, such as the Asian Development Bank, only require donors to pay-in 5% of their total contributions, while the remaining can be leveraged from markets because of the donor pool’s high credit rating. There are also benefits to the recipient in terms of offering a less expensive option than market loans and leveraging larger investments from donors.

A number of bilateral donors engage in concessional finance. Of the 29 OECD countries, 16 have engaged in concessional finance (including Australia) in the past decade, but only 7 of them substantively. In the past decade 92% of all bilateral lending has come from just three donors — Japan, France and Germany. All have specialist agencies managing their aid programs.

Table 3: Concessional bilateral lending, 2007–16

|

Volume |

% Share of total aid |

|

|

Japan |

69.11 |

53% |

|

France |

25.13 |

34% |

|

Germany |

22.87 |

20% |

|

Korea |

4.48 |

40% |

|

Spain |

2.41 |

11% |

|

Portugal |

1.43 |

48% |

|

Italy |

1.15 |

8% |

|

Australia |

0.30 |

1% |

|

Canada |

0.30 |

1% |

|

Poland |

0.20 |

41% |

|

Belgium |

0.19 |

1% |

|

DAC Countries, Total |

127.74 |

13% |

|

Total concessional lending |

305.87 |

21% |

Source: OECD QWIDS database

Multilateral agencies, particularly multilateral development banks, are much more heavily engaged in concessional finance. Some 52% of all aid from multilateral aid agencies involved in lending over the past decade has come in the form of concessional finance. Some multilateral donors, such as the Asian Development Bank and World Bank, are heavily specialised in development finance, and operate at a scale far larger than the Australian bilateral aid program.

Table 4: Concessional multilateral lending, 2007–16

|

Volume |

% Share of total aid |

|

|

World Bank Group |

85.94 |

81% |

|

EU Institutions |

27.70 |

20% |

|

African Development Bank |

11.91 |

54% |

|

Asian Development Bank |

11.80 |

76% |

|

International Monetary Fund |

11.75 |

86% |

|

Arab Fund |

6.85 |

97% |

|

Inter-American Development Bank |

5.51 |

41% |

|

OPEC Fund for International Development |

2.56 |

91% |

|

Islamic Development Bank |

1.09 |

89% |

|

Council of Europe Development Bank |

0.56 |

98% |

|

Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa |

0.52 |

95% |

|

Nordic Development Fund |

0.19 |

45% |

|

Caribbean Development Bank |

0.07 |

75% |

|

Total |

166.45 |

52% |

Source: OECD QWIDS database

While there are clear advantages in prioritising concessional lending over grants for infrastructure investments, there are also a number of risks associated with engaging in concessional financing.

The first is the risk of exposing recipient countries to further debt, and potentially debt distress. This was exhibited most clearly in the 1990s when 36 developing countries — 30 of which were in Africa — were identified as having unsustainable or unmanageable debt burdens. The Heavily Indebted Poor Country Initiative (HIDP), launched in 1996, has since relieved (written off) $99 billion in debt to these countries. The HIDP program has led to a great deal of debate about the role and utility of concessional finance. The potential for writing down of debt in the future presents significant liabilities for a concessional lending operation. Some representatives of the Australian government, for example, have been particularly critical of the potential for debt distress in relation to Chinese aid in the Pacific region.

Related to this risk is the need for donors engaging in lending activities to have the appropriate skills and expertise to ensure that loan finance is used appropriately, that projects are fully implemented and achieve the desired development impact, that debt sustainability of the recipient country is not threatened, and that the loan is repaid. These are all complicated requirements. The taskforce to manage the Coral Sea Cable project, a $136 million initiative, is made up of more than 10 full-time staff in DFAT’s Pacific division, close to 10% of the entire division. Allocating such a large number of finite human resources within the Department comes with diplomatic and development trade-offs.

These skills are also particularly necessary in the Pacific, where there is a shortage of ‘bankable’ projects, operating costs are significant, and a significant amount of technical assistance is required to effectively implement projects. The Asian Development Bank and World Bank, following intense lobbying from Australia, are committed to scaling up their own lending to the Pacific. Any bilateral concessional lending from Australia must not cannibalise the pipeline of projects that these multilateral agencies, and indeed other bilateral agencies, are working to establish.

Despite these risks, there are advantages to concessional lending. The Coral Sea Cable is a clear example of an initiative which the Australian aid program simply does not have the resources to routinely fund through grant funding without significantly disrupting other parts of the aid program, and for which concessional lending is viable (and had been proposed in the past). A bilateral lending agency, assuming it can be more nimble and responsive than multilateral agencies, would also better align with Australia’s strategic interest. It would help to bring more profile to Australia’s aid efforts, both at home and in the region.

It would also be a significant change for Australia’s aid program, particularly after the disruption of the past five years. We should proceed with caution.

Recommendation 6: A specialised agency should be established to manage Australian concessional financing that is adequately staffed and resourced to identify a pipeline of bankable projects and leverage Australian private sector financing.

6. Aid transparency

Aid transparency is critical for a number of reasons. How aid money is used and where it actually goes is of interest to many people around the world. Transparency also contributes to the aid effectiveness agenda by giving developing-country governments information to help them allocate resources; giving civil society information needed to hold governments to account; assisting multiple development actors to coordinate their aid efforts; and helping people who care about development share and learn from their experiences. It also helps donors to learn from one another, and from the past.

In the new aid ‘paradigm’, Minister Bishop dropped aid transparency as a key element of the aid program’s new performance framework. The last government, despite routine commitments and investing significantly in transparency, still struggled to keep project information up-to-date on the web. An audit of project-level availability of data on the DFAT website in 2016 found project-level data to be lacking, with only half of the projects assessed having accompanying documentation. The PNG Governance Facility, a five year $350 million initiative, for example, only provides a design document. There is no accompanying website, and scant detail on what projects this facility actually delivers. This is common across the board.

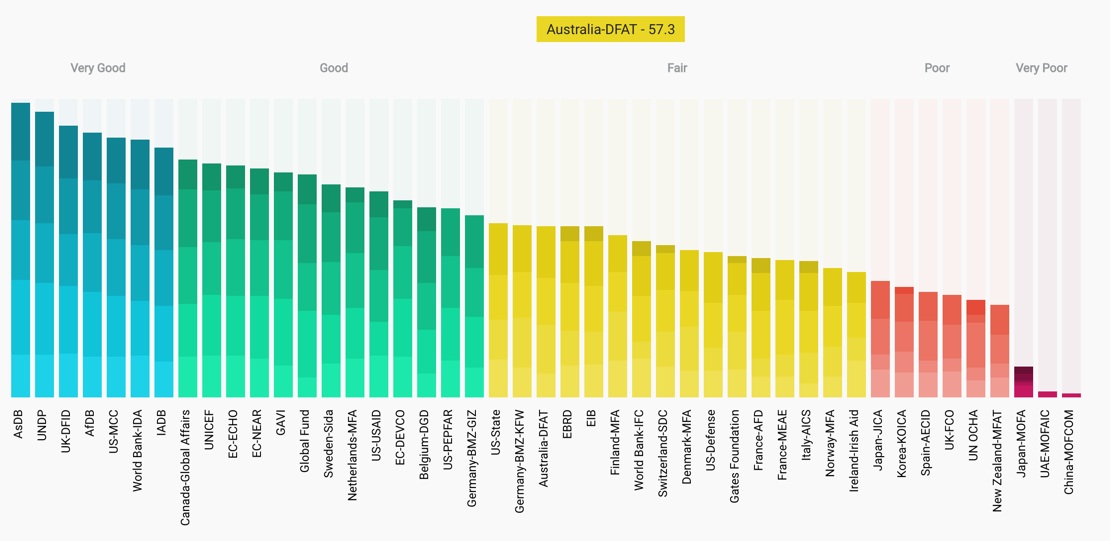

Despite the shortcomings of DFAT’s website, Australia still ranks in the middle of the pack globally according to the 2018 Aid Transparency Index, ranking 23rd out of 45 donors measured. This is largely because this index relies heavily on how donors report to the International Aid and Transparency Initiative (IATI), an international reporting mechanism. While reporting to international registries like IATI (and importantly maintaining our reporting commitments to the OECD) is laudable, it should not come at the cost of having accessible and comprehensive project-level information on the DFAT website.

Figure 5: 2018 Aid Transparency Index

Source: Publish What You Fund

As director of the Pacific Islands Program of the Lowy Institute, I strongly believe in the potential of aid transparency to improve aid accountability and effectiveness. With support from the Australian aid program the Institute has spent the last 18 months building the Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map, which will be launched on 9 August 2018. This is an analytical tool designed to enhance aid effectiveness in the Pacific by improving coordination, alignment, and accountability of foreign aid. The interactive collects data on almost 13,000 projects in 14 countries from 62 donors from 2011 onwards. This raw data has been made freely available on an interactive multifaceted platform, allowing users to examine and manipulate the information in a variety of ways.

While this project is a critical complement to donors’ individual transparency efforts, it is not a substitute. It shows only inputs into aid, not the performance of individual projects. For that, donors will still have to provide their own detailed public reporting.

As such, it should be made policy within DFAT that every project over the sum of $1,000,000 has an accompanying website. This should be the responsibility of the signing delegate of the project, rather than the DFAT statistics team or locally based staff. This could be done with marginal ongoing investment through automating as much of the process as possible, rather than relying on manual entry as is currently the case.

DFAT’s internal aid reporting system, AidWorks, is currently under redevelopment. A component of this could be to create a system within AidWorks that can automatically create websites populated with publicly cleared data as the delegate authority signs off on a project. Agencies including MFAT, ADB, and others have taken this automated approach. Closer to home, the Australian Council for International Agricultural Research provides reasonable project-level information on every active research project (many of which are supported by Australian aid).

Recommendation 7: Transparency of Australian aid must be improved. Every aid project over $1,000,000 should have (through AidWorks) an automatically generated, publicly accessible, website.

7. Conclusion

This Parliamentary inquiry comes at an opportune time. The Australian aid program has undergone significant strain over the past five years, and more change is necessary to make sure that the long-term objectives and effectiveness of aid are preserved. But these changes should not be dramatic or radical. They should be well considered and implemented over time to ensure that the disruption and short-term costs of change can be marginalised. I thank the Committee for the opportunity to make this submission, and I look forward to discussing my recommendations in more detail, should the Committee be interested.

Disclaimer

This submission represents the personal views of its author, Jonathan Pryke, and may not reflect the broader perspective of the Lowy Institute. The Lowy Institute’s Pacific Islands Program receives support from the Australian aid program.