Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is one of President Xi’s most ambitious foreign and economic initiatives. It reflects a combination of economic and strategic drivers, not all of which can be easily reconciled. Photo: Flickr/Johannes Zielcke.

- There are strategic drivers behind China’s Belt and Road Initiative, but it is also motivated by the country’s pressing domestic economic challenges.

- The combination of strategic and economic drivers is not always easy to reconcile. In some cases, China’s strategic objectives make it difficult to sell the economic aspects of the initiative to China’s neighbours.

- The Chinese Government is keen to use the initiative to achieve important economic policy objectives, but some Chinese financiers and policymakers are cautious about funding risky Belt and Road projects outside of China, fearing poor return on their investments.

Executive summary

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR)) is one of President Xi’s most ambitious foreign and economic policies. It aims to strengthen Beijing’s economic leadership through a vast program of infrastructure building throughout China’s neighbouring regions. Many foreign policy analysts view this initiative largely through a geopolitical lens, seeing it as Beijing’s attempt to gain political leverage over its neighbours. There is no doubt that is part of Beijing’s strategic calculation. However, this Analysis argues that some of the key drivers behind OBOR are largely motivated by China’s pressing economic concerns.

One of the overriding objectives of OBOR is to address China’s deepening regional disparity as the country’s economy modernises. Beijing hopes its transnational infrastructure building program will spur growth in China’s underdeveloped hinterland and rustbelt. The initiative will have a heavy domestic focus. The Chinese Government also wants to use OBOR as a platform to address the country’s chronic excess capacity. It is more about migrating surplus factories than dumping excess products. One of the least understood aspects of OBOR is Beijing’s desire to use this initiative to export China’s technological and engineering standards. Chinese policymakers see it as crucial to upgrading the country’s industry.

Introduction

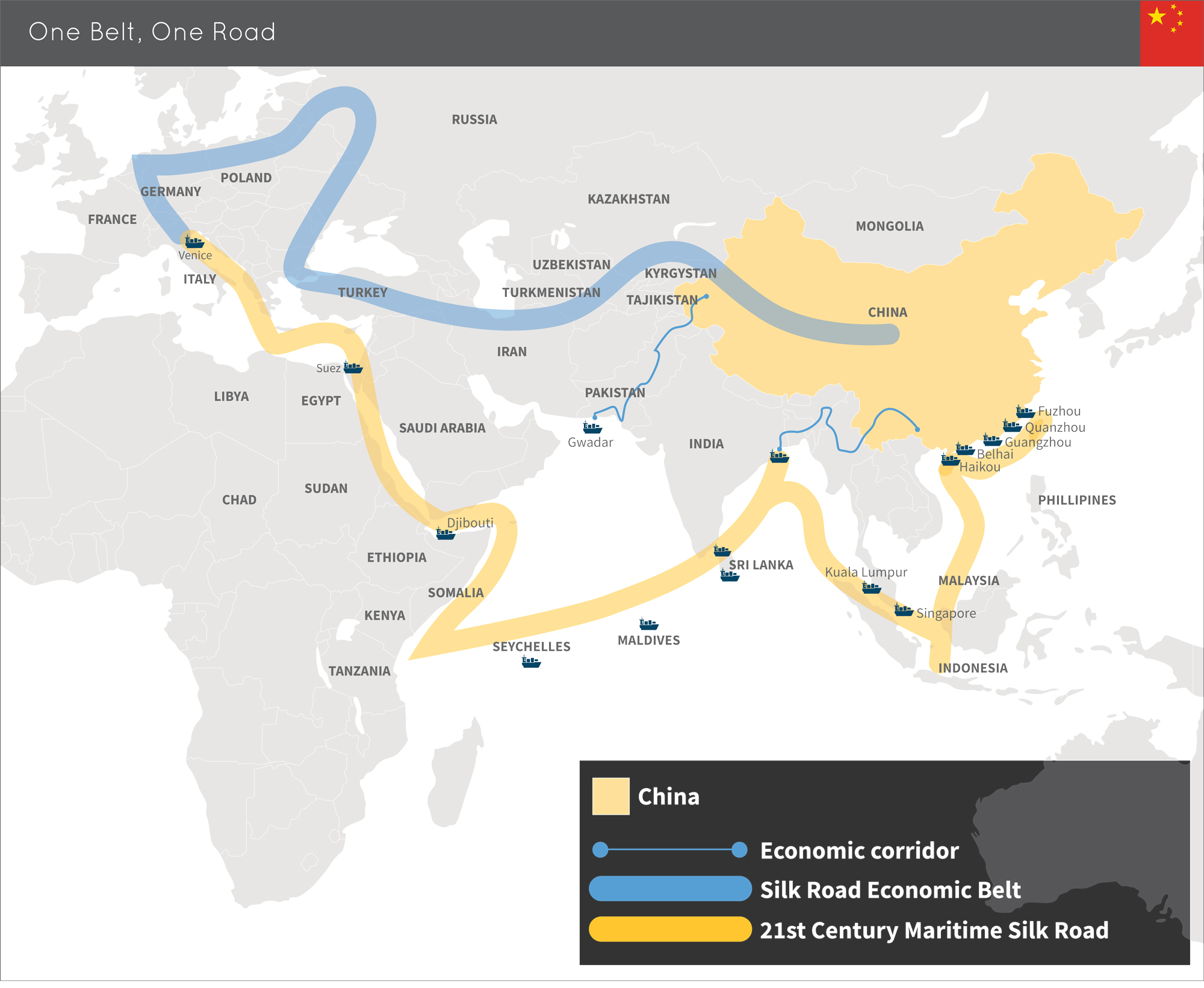

At the end of 2013 Chinese President Xi Jinping announced one of China’s most ambitious foreign policy and economic initiatives. He called for the building of a Silk Road Economic Belt and a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, collectively referred to as One Belt, One Road (OBOR) but which has also come to be known as the Belt and Road Initiative. Xi’s vision is an ambitious program of infrastructure building to connect China’s less-developed border regions with neighbouring countries. OBOR is arguably one of the largest development plans in modern history.

On land, Beijing aims to connect the country’s underdeveloped hinterland to Europe through Central Asia. This route has been dubbed the Silk Road Economic Belt. The second leg of Xi’s plan is to build a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road connecting the fast-growing Southeast Asian region to China’s southern provinces through ports and railways.

All levels of the Chinese Government, from the national economic planning agency to provincial universities, are scrambling to get involved in OBOR. Nearly every province in China has developed its own OBOR plan to complement the national blueprint. Major state-owned policy and commercial banks have announced generous funding plans to fulfil President Xi’s ambitious vision.

Xi has launched OBOR at a time when Chinese foreign policy has become more assertive.[1] This has meant that OBOR is often interpreted as a geopolitical plan rather than a purely economic one. While there is a great deal of truth to this interpretation, this Analysis argues that focusing on the geopolitical dimensions of OBOR obscures its principally geoeconomic drivers, in particular its connection to changes in China’s domestic industrial policy.

OBOR: Geostrategy or geoeconomics?

Before the 18th Party Congress in 2013, there were heated debates among Chinese policymakers and scholars about the strategic direction of the country’s foreign policy,[2] especially in its neighbourhood.[3] In October 2013 Beijing convened an important work conference on what it termed ‘peripheral diplomacy’. It was reportedly the first major foreign policy meeting since 2006 and the first-ever meeting on policy towards neighbouring countries since the founding of the People’s Republic. It was attended by all of the most important players in the Chinese foreign policymaking process, including the entire Standing Committee of the politburo.[4]

At the Peripheral Diplomacy Work Conference, Xi said that China’s neighbours had “extremely significant strategic value”. He also said that he wanted to improve relations between China and its neighbours, strengthening economic ties and deepening security cooperation.[5]

“Maintaining stability in China’s neighbourhood is the key objective of peripheral diplomacy. We must encourage and participate in the process of regional economic integration, speed up the process of building up infrastructure and connectivity. We must build the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, creating a new regional economic order.”[6]

Xi clearly sees China’s considerable economic resources as a key tool in his efforts to maintain regional stability and assert China’s leadership in the country’s neighbourhood. Analysts regard the work conference as a significant turning point in the evolution of China’s foreign policy. Douglas Paal of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace argues that the conference saw the Chinese leadership effectively bury former leader Deng Xiaoping’s famous dictum, “hide your strength and bide your time”. According to Paal, in its place, the new Chinese leadership have advanced a more proactive diplomacy in surrounding regions.[7]

This new more activist foreign policy has reinforced the impression that OBOR is primarily driven by broad geostrategic aims. Certainly some elements of OBOR are consistent with such a characterisation. The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor is a prime example. It is widely regarded as one of the flagship projects of OBOR and is enthusiastically supported by both Beijing and Islamabad. The proposed corridor is expected to connect Kashgar in Xinjiang in China’s far west with the Port of Gwadar in the province of Baluchistan. Given the port’s proximity to the Persian Gulf, it could be used as a transhipment point for China’s energy supplies obviating the need to go through the Strait of Malacca in Southeast Asia.[8]

Source: Pakistan Government

Apart from serving as a commercial port, Gwadar is also deep enough to accommodate submarines and aircraft carriers. Indeed, the military logic behind the development of the port is becoming increasingly prominent as the People’s Liberation Army Navy embarks on far-flung activities from anti-piracy missions in the Arabian Sea to the evacuation of Chinese workers in Libya.[9]

At a broader strategic level, influential Chinese policymakers and analysts have also argued that OBOR could be used as a strategic tool to counter the Obama administration’s pivot to Asia. In 2015 Justin Yifu Lin, an influential policy adviser and a former chief economist at the World Bank, argued President Xi had launched OBOR to counterbalance US policies such as the pivot and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). He argued China should use its economic resources including its large foreign reserves and experience in building infrastructure to strengthen its position in the region.[10] One Counsellor at the State Council of the Chinese Government, Tang Min, noted that China and many emerging economies had been locked out of the US-led TPP and these countries needed a ‘third pole’, namely OBOR.[11]

The election of Donald Trump as President of the United States in 2016 and his rejection of the TPP in January 2017 will help the Chinese leadership to sell OBOR more effectively. As Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong warned in a visit to Washington in August 2016, the US rejection of the TPP will damage its reputation among regional allies.[12]

President Xi wasted no time in promoting China as the new global champion of free trade. Chinese diplomats have been busy hawking Beijing-backed regional trade deals such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and OBOR.[13] There are early indications that some US regional allies are already gravitating towards Beijing on issues of economic leadership. For example, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has warmly embraced Beijing despite the country’s troubled relationship with China over disputed South China Sea islands.[14]

Geoeconomics

The problem with narrow geostrategic interpretations of OBOR is not that they are wrong but that they are incomplete. Many analysts tend to overstate geostrategic dimensions of the project, while underappreciating the economic agenda of OBOR.[15] The two goals are not, in fact, contradictory. China is using OBOR to assert its regional leadership through a vast program of economic integration. Its aim is to create a regional production chain, within which China would be a centre of advanced manufacturing and innovation, and the standard setter.

But it is also true that OBOR will help China to meet some of its most pressing economic challenges. Of these challenges, three in particular are important in understanding the key aims of OBOR: encouraging regional development in China through better integration with neighbouring economies; upgrading Chinese industry while exporting Chinese standards; and addressing the problem of excess capacity.

OBOR and regional development

The regional development aspect of OBOR is perhaps one of China’s most important economic policy objectives. The lead coordinating government agency for OBOR is the National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s premier economic planning agency. It is likely that Chinese domestic components of OBOR projects will be built before any overseas components for the simple reason that Beijing can enforce its plans much more effectively within its own jurisdiction. However, if the Chinese Government fails to connect its domestic projects with overseas components, OBOR will be little different from other domestic infrastructure programs, greatly diminishing its economic and strategic value.

In 2014 OBOR was officially incorporated into China’s national economic development strategy at the Central Economic Work Conference, the annual agenda-setting economic summit for policymakers. Beijing announced three regional development plans, one of which was OBOR.[16] These regional development plans are designed to address the chronic problem of uneven development in China.

Inequality between inland western regions and prosperous eastern seaboard states is a huge challenge for the ruling party. For example, the coastal mega-metropolis of Shanghai is five times wealthier than the inland province of Gansu, which is part of the old Silk Road.[17]

Beijing has tried to close the gap between these provinces. Since 1999 the Chinese Government has pursued the so-called ‘western development strategy’ to revitalise chronically underperforming provinces including the majority Muslim autonomous region of Xinjiang. However, these efforts have produced few tangible results. Despite Beijing’s preferential policies, large-scale fiscal injections and state-directed investments, the western provinces’ share of China’s total GDP increased only marginally from 17.1 per cent in 2000 to 18.7 per cent in 2010.[18]

One acute side effect of heavy state subsidies in these western provinces has been a high concentration of state-owned enterprises and low penetration of private firms. For example, the western regions of Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, and Gansu are the four lowest-ranked provinces on the China Economic Research Institute’s Free Market Index.[19] Their average score is 2.67 (0 means no private enterprise and 10 means completely free); the national average is 6.56.[20]

Beijing is keen to try different approaches to reinvigorate these underperforming provinces and OBOR has been touted as one of the key solutions. The economic rationale behind it is simple enough; instead of showering these provinces with more central government money, Chinese policymakers want to integrate them into regional economies.

Xinjiang offers an interesting case study. As already noted, one of the most important flagship projects of OBOR is the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, which links Kashgar in Xinjiang with the Port of Gwadar. This project, which is estimated at $46 billion, is also the clearest example of where OBOR’s geostrategic rationale intersects with its economic drivers.

Xinjiang has a large Turkic-speaking Muslim population which has grown increasingly frustrated with Beijing’s rule. Since the 1990s, Xinjiang has also become the main source of terrorism within China. “Aspirations towards greater autonomy or outright independence have never been far from the surface of political life in the province”, notes Andrew Small, a leading expert on China–Pakistan relations.[21] The spread of radical Islamism in Xinjiang is adding further complexity to an already tense situation.

The ruling Communist party regards Xinjiang’s separatist movement as an existential threat to the party state. Beijing believes poverty and underdevelopment is at the heart of rising militancy in the restive province and that the best strategy to address the root cause is integrating Xinjiang with the neighbouring region.[22]

A former Chinese ambassador to Islamabad, Lu Shuling, argues the construction of the Port of Gwadar is economically vital for landlocked Xinjiang, which is 4000 to 5000 kilometres away from China’s coastal ports. Lu believes the port will significantly reduce the transport costs for the province. He further argues that the economic benefits of the corridor will help to solve Pakistan’s and Xinjiang’s political problems: “The best medicine to address the terrorism problem is through tackling the incubator of terrorism, namely poverty.”[23] The head of the Chinese Central Bank in Xinjiang has made a similar argument, noting that better connectivity between the province and the Central Asian region will bring both “economic and national security dividends”.[24]

Apart from developing the western region, OBOR is also expected to play an important role in revitalising economically underperforming provinces in the north-east as well as other poor regions in the south-west, bordering Southeast Asia. In fact, all Chinese provinces are keen to be involved in the national project. Many see it as a golden opportunity to obtain cheap funding and political support for their own infrastructure projects under the banner of OBOR.

Guan Youqing, the head of Minsheng Securities Research Institute and one of the China’s most respected equity analysts, says all provinces are competing fiercely against each other for OBOR-related projects. Every province wants to become a significant hub in the national strategy and he believes this will reignite infrastructure spending by local governments. Guan estimates all provinces have earmarked just over a trillion renminbi for OBOR-related infrastructure projects; 68 per cent of them will be related to railway, road and airports. Guan estimates this will add 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points to China’s GDP growth, although this estimate needs to be treated with a degree of caution.[25]

Upgrading Chinese industry while exporting Chinese standards

China has developed an impressive reputation as the ‘world’s factory’ over the last three decades. In recent years, however, its comparative advantages in manufacturing, such as low labour costs, have begun to disappear. For this reason, the Chinese leadership wants to capture the higher end of the global value chain.

To do this, China will need to upgrade its industry. Indeed, this has become one of China’s most important domestic economic goals. It is reflected in the so-called Made in China 2025 strategy,[26] drafted by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). The strategy was inspired by Germany’s “Industry 4.0” plan. Its primary goals are to make the country’s manufacturing industry more innovation-driven, emphasise quality over quantity, and restructure China’s low-cost manufacturing industry.[27]

Beijing expects OBOR to play an important role in facilitating the export of higher-end Chinese manufactured goods. Chinese policymakers believe emerging markets targeted under OBOR will be more willing to accept higher-end Chinese industrial goods than developed countries in North America and Europe.

China is not just trying to export higher-end goods through OBOR but to encourage the acceptance of Chinese standards. The Chinese Government’s focus on exporting its technological standards must be understood in terms of its broader ambition to become an innovation-based economy and a leader in research and development. According to a research report prepared on behalf of the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission, “Policy makers see development of technology standards as central to realizing these objectives”.[28]

There is a popular saying in China that “Third-tier companies make products, second-tier companies make technology and first-tier companies make standards”. There is a pervasive belief within China, particularly in policy circles and academia, that only companies that make standards can be considered world-class companies.[29]

Xu Jing, head of the MIIT-affiliated Smart Manufacturing Institute, says OBOR will play a key role in helping Chinese companies to become more internationally competitive.[30] Under OBOR, Chinese companies and especially higher-end industrial goods manufacturers will be encouraged and expected to operate in more demanding markets and more stringent regulatory environments. The expansion of a China-centred production chain will also force Chinese manufacturers to move higher up in the value chain. These efforts will be supported by Chinese financiers, who often urge loan recipients to accept Chinese-made goods as a condition of extending credit.

The Chinese Government’s campaign to market its high-speed railway technology is perhaps the best example of how it intends to use OBOR to upgrade China’s industry. Many have dubbed Premier Li’s marketing effort in this area as ‘high-speed railway diplomacy’.

Beijing considers its high-speed railway technology to be one of the crown jewels of its advanced manufacturing industry. The Chinese Government has mobilised more than 10 000 scientists and engineers to incorporate imported foreign technology as well as to develop the country’s own high-speed rail technology.

The result of this effort is evident in the breathtaking development of China’s high-speed rail sector. Today the country is home to more than 50 per cent of the world’s total constructed high-speed railway. Premier Li Keqiang has personally marketed Chinese-made high-speed to Thailand, India, Indonesia, and Malaysia.[31] All of these countries are considered to be key strategic partners in OBOR.

The focus on high-speed rail also illustrates Beijing’s goal of gaining acceptance of Chinese standards. If countries across the region accept Chinese high-speed railway technology as their national standard, it could become the de facto standard across a vast geographical area. This means Chinese manufacturers and suppliers would enjoy a strong, first-mover advantage over other competitors, especially Japanese producers of high-speed rail.

In a policy document released by the MIIT on the development of the transport industry, the high-speed rail sector is expected to play a leading role in encouraging high-end Chinese industrial exports. It estimates the market for transport equipment to be around $263 billion by 2018. Chinese planners believe significant demand will come from regions covered by OBOR such as Southeast Asia, South Asia, Central Asia, and West Asia.[32]

The Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Railway project is a good example of how Beijing intends to use OBOR to promote the high-tech sector as well as Chinese technical and engineering standards. Beijing secured the right to build the 142 kilometre high-speed rail line connecting the Indonesian capital and Bandung in West Java after an intense bidding war with the Japanese.[33] Beijing won the bid by offering to finance the project itself.[34] In order to win over Indonesian President Joko Widodo, Xi Jinping even dispatched the Chairman of the National Development and Reform Commission, Xu Shaoshi, as a special envoy to Jakarta.

The most significant part of the deal for Beijing is the Indonesian Government’s decision to adopt Chinese high-speed railway technology. Xinhua, the Chinese Government official news agency, has reported that the project will adopt “Chinese standards, Chinese technology and Chinese equipment” and that a Chinese engineering company will be involved in every aspect of construction, from the initial survey to the management of the railway once the project is completed.[35] For Beijing, this deal might be a loss-making venture, but it is a major breakthrough in persuading a foreign country to accept Chinese standards and technology.

Apart from the high-speed rail sector, the Chinese Government is also using OBOR to push for Chinese standards in other sectors such as energy and telecommunications. Ru Quan Lu, Director of Strategic Development at Petro China, argues that China should use its extensive investment in oil and gas projects in Central Asian states to promote Chinese petroleum industry standards:

“Based on the experience of American and European energy majors, controlling standards means having an upper hand in negotiation, more bargaining chips and better profitability. To control standards is more important than anything else.”[36]

Telecommunications is another important sector in terms of gaining acceptance of Chinese standards. China boasts two world-class telecommunication equipment makers: Huawei and ZTE. The former derives 70 per cent of its sales revenue from outside of China and is particularly successful in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Huawei, ZTE, and China Mobile are closely involved in developing 5G technology, which includes setting and designing international technical standards. These companies are becoming active participants in many international telecommunication industry bodies and associations such as the International Telecommunications Union, the 3rd Generation Partnership Project, and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Beijing sees the telecommunications industry as central to its Made in China 2025 strategy.[37]

It is no coincidence, therefore, that the Chinese Government envisages building telecommunication networks as a key part of OBOR. Hu Huaibang, Chairman of the China Development Bank, one of the world’s largest banks, specifically named the telecommunications sector as one of the key industries that his bank wants to support as part of OBOR, noting: “This will have an enormously positive impact on upgrading China’s industrial structure.”[38]

Dealing with excess capacity

During the global financial crisis, the Chinese Government delivered one of the largest stimulus packages in recent economic history. It saved China (and arguably a host of other countries, including Australia) from recession by sending commodity prices sky-high. Though the stimulus program was effective, one of its lasting side effects was the creation of massive excess capacity in many industrial sectors from steel to cement. In the steel industry, for example, China’s annual steel production surged from 512 million tonnes in 2008 to 803 million tonnes in 2015. To put that into perspective, the extra 300 million tonnes is larger than the combined production of the United States and the European Union.[39]

Dealing with the country’s excess capacity has become one of the top economic priorities for the Chinese Government. Beijing has described this issue as the sword of Damocles hanging over its head. Excess capacity will squeeze corporate profits, increase debt levels, and make the country’s financial system more vulnerable.[40]

Many state-owned firms in sectors with excess capacity borrowed heavily during the financial crisis. The slowing economy, sluggish international demands, and the supply glut have reduced their profits. Many are struggling to keep their heads above water. These bad loans have put the Chinese banking system under a great deal of stress.

The Chinese Government has announced a number of policy measures to address the issue of excess capacity. This has included laying off 1.8 million workers from the steel and coal mining industries.[41] The authorities are also trying to shut down polluting steel mills and blast furnaces.

OBOR is another way for Chinee policymakers to address the excess capacity problem, although not in the way that some observers believe. When Xi Jinping announced OBOR, a number of observers labelled it as an effort by China to export excess industrial products to neighbouring countries. The Financial Times reported in 2015 that the grand vision for a new Silk Road began its life modestly in the bowels of China’s commerce ministry as an export initiative.[42]

In terms of addressing the excess capacity problem, OBOR is less about boosting exports of products such as steel and more about moving the excess production capacity out of China. OBOR projects are currently too small to absorb China’s vast glut of steel and other products. Instead, Beijing wants to use OBOR to migrate whole production facilities. Chinese premier Li Keqiang made the point clear in his address to leaders of ASEAN countries in 2014 at Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar:

“We have a lot of surplus equipment for making steel, cement and pleat glass for the Chinese market. This equipment is of good quality. We want companies to move this excess production capacity through direct foreign investment to ASEAN countries who need to build their infrastructure. These goods should be produced locally where they are needed.”[43]

Hu Huaibang, Chairman of the China Development Bank and the most influential financier of OBOR projects, says one of the most important objectives of OBOR is to help China undergo economic structural reform and upgrade its industries, moving away from the cheap mass manufacturing model:

“On the one hand, we should gradually migrate our low-end manufacturing to other countries and take pressure off industries that suffer from an excess capacity problem. At the same time, we should support competitive industries such as construction engineering, high-speed rail, electricity generation, machinery building and telecommunications moving abroad.”[44]

Moving factories with excess capacity to OBOR countries helps China reduce the supply glut at home while helping less developed countries to build up their industrial bases. In essence, domestic economic liabilities become foreign economic and diplomatic assets. Jin Qi, the Chairman of the Silk Road Fund, a sovereign wealth fund set up in 2014 specifically to provide seed capital for OBOR projects, made this clear during one of her rare public speeches on OBOR.[45]

Jin said China currently sits in the middle of the global production chain and it can help countries at an early stage of development to industrialise: “China possesses high-quality industrial production capacity, equipment, technology, ample supply of funds and 30 years of development experience.” She also noted that Chinese capital can “help facilitate international production cooperation, and reorganise global production chain. For China, it means helping the country to export high-quality production capacity, equipment, technical know-how and developmental experience.”[46]

Part of this thinking is informed by China’s own experience of industrialisation in the 1980s and 1990s. One senior provincial economic planning official said China imported second-hand production lines from Germany, Taiwan, and Japan in the 1980s; essentially unwanted surplus industrial capacity.[47] Beijing thinks China’s experience could be replicated in neighbouring, less-developed countries.

One clear example of this is the plan to migrate part of Hebei province’s massive surplus steel production facilities. The province, China’s largest producer of steel, wants to relocate 20 million tonnes of production capacity abroad by 2023. The plan calls for companies to move their excess steel (but also cement and pleat glass production) facilities to Southeast Asia, Africa, and West Asia. For example, Delong Steel from Xintai is building a steel mill in Thailand that is capable of producing 600 000 tonnes of hot rolled coil a year in partnership with a local Thai operator, Permsin Steel Works.[48]

Some Chinese researchers and officials are sceptical of how successful this aspect of OBOR is likely to be. It is questionable whether OBOR countries can actually absorb China’s vast surplus production line. More importantly, will it be politically palatable for other countries to simply accept China’s unwanted industrial capacity?

Analysis from Anbang Research has noted that many OBOR countries are not enthusiastic about accepting China’s excess capacity. In fact, some countries are hostile to the idea because in several industrial sectors, they are competing directly with China.

“In the foreseeable future, Belt and Road countries are unlikely to experience the same rapid pace of urbanisation China had enjoyed in the last decade. The current problem of excess capacity is of a global nature; the Belt and Road Initiative is unlikely to solve it.”[49]

One of China’s most senior policy advisers, Zheng Xin Li, a former deputy head of the Policy Research Office of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, has expressed his concerns about the massive migration of Chinese manufacturing to Southeast Asia and South Asia.

“There are still 240 million farmers (in China) who need to find manufacturing jobs. If most of the country’s labour-intensive industry moves abroad, all these surplus farm labours will be stuck in the countryside.”[50]

Implementation challenges: Lack of bankable projects and moral hazard

Chinese leader Xi Jinping launched OBOR at the end of 2013. Three coordinating government agencies (the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce) issued the first official blueprint on OBOR, the ‘Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road’, just two years later in March 2015. However, there has been slow progress in terms of the implementation of projects outside of China.

At a recent OBOR work conference chaired by Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee who is overseeing the initiative, Xi urged for some signature projects to be implemented quickly, showing tangible benefits and early success. He wanted the focus to be on infrastructure projects that improve connectivity, deal with excess capacity, and trade zones. “We need to get some model projects done and show some early signs of success and let these countries feel the positive benefits of our initiative”, he told a large gathering of senior party officials and business people.[51] Xi is not happy with the lack of progress, not least because OBOR is part of his political legacy. But the initiative faces multiple, formidable challenges.

First, there is a significant lack of political trust between China and a number of important OBOR countries. Perhaps the best example of this is India. The country’s Foreign Secretary Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has said OBOR is a unilateral initiative and that India would not commit to buy-in without significant consultation.[52] Sameer Patil, a former assistant director at the Indian National Security Council and a researcher at foreign policy think tank Gateway House, says the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor project is a major obstacle to Indian involvement in the initiative.[53]

A second problem is that nearly two-thirds of OBOR countries have a sovereign credit rating below investable grade. Some key OBOR countries such as Pakistan are unstable, which poses significant security risks to Chinese companies as well as personnel working there.[54] The Pakistani military has, for example, promised to raise a special military unit of 12 000 soldiers to protect China–Pakistan Economic Corridor projects.

A third problem is caution on the part of over-leveraged and risk-averse Chinese financers. After Xi announced OBOR, Chinese state-owned financial institutions followed with a raft of policies that echoed the president’s grand vision. China Development Bank, which is expected to play a key role in financing OBOR, says it is tracking more than 900 projects in 60 countries worth more than US$890 billion.[55] Bank of China, which has the largest overseas networks, pledged to lend US$20 billion in 2015 and no less than US$100 billion between 2016 and 2018.[56] Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) has been looking at 130 commercially feasible OBOR-related projects worth about US$159 billion. It has financed five projects in Pakistan and has established a branch in Lahore.[57]

Yet, despite these public pledges of support, many Chinese bankers and especially those from listed commercial banks such as ICBC are concerned about the feasibility of OBOR projects. They are worried about the many risks associated with overseas loans, including political instability and the economic viability of many projects. As Andrew Collier, Managing Director of Orient Capital Research, has noted: “It is pretty clear that everyone is struggling to find decent projects. They know it’s going to be a waste and don’t want to get involved, but they have to do something.”[58] Collier gave an example of one Beijing bank that he said had stopped lending to rail projects in risky places such as Baluchistan in Pakistan.

A chief investment officer from one of China’s largest state-owned financial institutions also told the author about his own reservations: “I prefer to invest in places like Canada and Australia, where I can get safe and decent returns. However, where I have been ordered to invest in OBOR countries, I will only allocate the minimum amount.”[59]

The reservations of Chinese financiers and businesspeople about OBOR also need to be seen in the context of the worsening debt problem within China’s financial system, especially the number of non-performing loans on banks’ balance sheets. This rapid pile-up of debts took place after the country’s massive stimulus package of 2008. China’s leading business magazine, Caixin, has suggested that OBOR could produce a repeat of 2008.[60] Influential economic policymakers in China are also concerned that the political impetus behind OBOR could drive China into investing in white elephant projects abroad. They are worried that some countries will take advantage of OBOR and sign up to Chinese projects with no intention of repaying the loans.[61]

Yiping Huang, an influential economist who sits on the Chinese central bank’s monetary policy committee and a former investment banker, has argued that China needs to proceed cautiously on OBOR projects:

“The most effective way to promote the initiative is by getting one or two projects done. If they turn out to be effective, it will be easier to take the next step. If early projects are disastrous, the future path will be hard.”[62]

Huang has also noted the efforts to develop the country’s western region largely failed because the state ignored the fundamental economic issue of ensuring a return on assets.[63]

There are indications that Chinese financiers are demanding tougher terms to ensure OBOR projects are financially viable over the longer term. Negotiations with the Thai Government over the building of a high-profile rail project were hamstrung by disagreements over interest rates, among other things.[64] Chinese financiers demanded a 2.5 per cent return on their concessional loan while the Thai Government wanted 2 per cent, the same rate Beijing offered to Jakarta. When Chinese bankers insisted on 2.5 per cent Bangkok said it would finance the project itself. Xue Li, a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a member of a semi-official OBOR expert panel, says China is likely to lose money on the Indonesian high-speed rail deal, which Beijing is treating as a one-off special case and does not want the generous funding terms to become the norm.

Conclusion

OBOR is President Xi’s most ambitious foreign and economic policy initiative. Much of the recent discussion has concerned the geopolitical aspects of the initiative. There is little doubt that the overarching objective of the initiative is helping China to achieve geopolitical goals by economically binding China’s neighbouring countries more closely to Beijing. But there are many more concrete and economic objectives behind OBOR that should not be obscured by a focus on strategy.

The most achievable of OBOR’s goals will be its contribution to upgrading China’s manufacturing capabilities. Given Beijing’s ability to finance projects and its leverage over recipients of these loans, Chinese-made high-end industrial goods such as high-speed rail, power generation equipment, and telecommunications equipment are likely to be used widely in OBOR countries. More questionable, however, is whether China’s neighbours will be willing to absorb its excess industrial capacity. The lack of political trust between China and some OBOR countries, as well as instability and security threats in others, are considerable obstacles.

Chinese bankers will likely play a key role in determining the success of OBOR. Though they have expressed their public support for President Xi’s grand vision, some have urged caution both publicly and in private. Their appetite to fund projects and ability to handle the complex investment environment beyond China’s border will shape the speed and the scale of OBOR. There is a general recognition that this initiative will be a decade-long undertaking and many are treading carefully.

Notes

[1] Christopher K Johnson, “President Xi Jinping’s ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative: A Practical Assessment of the Chinese Communist Party’s Roadmap for China’s Global Resurgence”, CSIS Report, 28 March 2016, https://www.csis.org/analysis/president-xi-jinping’s-belt-and-road-initiative.

[2] Zhai Kun, 一带一路:大国之翼:一带一路引领中国:国家顶层战略设计于行动布局 [“One Belt and One Road: The Wings of a Great Nation”, in One Belt and One Road Leads China: Strategic National Design and Implementation Guideline], Caixin Media Editorial Department ed (Beijing: China Wenshi Publishing House, 2015).

[3] ‘Neighbourhood’ refers to a disparate group of states located east of the Ural Mountains and west of the Bering Straits, south of the Caucasus Mountains and east of the Bosphorus Strait and the Suez Canal, and includes 63 countries from Asia, Russia, and Oceania, according to Xue Li, a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: “一带一路背景下的中国周边外交方略 [China’s Neighbourhood Foreign Policy against the Backdrop of One Belt and One Road]”, Financial Times (Chinese edition), 11 January 2016, http://www.ftchinese.com/story/001065641.

[4] For a full discussion of China’s Peripheral Diplomacy Work Conference, see Michael D Swaine, “Chinese Views and Commentary on Peripheral Diplomacy”, China Leadership Monitor 44 (Summer 2014), http://www.hoover.org/research/chinese-views-and-commentary-periphery-diplomacy.

[5] “习近平在周边外交工作座谈会上发表重要讲话 [Xi Jinping’s Important Speech at the Peripheral Diplomacy Work Conference]”, Xinhua News Agency, 25 October 2013, http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2013-10/25/c_117878897.htm.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Douglas Paal, “Contradictions in China’s Foreign Policy”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 13 December 2013, http://carnegieendowment.org/2013/12/13/contradictions-in-china-s-foreign-policy-pub-53913 - comments.

[8] Dipankar Banerjee, “China’s One Belt and One Road Initiative — An Indian Perspective”, ISEAS Perspective, Issue 2016, No 14, 31 March 2016, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2016_14.pdf.

[9] Andrew Small, The China–Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics (London: Hurst & Company, 2015), 103–105.

[10] Justin YiFu Lin, 一带一路, 让中国市场经济体系更完善, 读懂一带一路,国家智库顶级学者前瞻中国新丝路 [“One Belt and One Road, Enables China to Perfect its Market Economy”, in Leading Scholars from National Think Tanks and Their Insights on China’s New Silk Road] (Beijing: CITIC Press, 2015), 5.

[11] Tang Min, 一带一路战略彰显大国心态,读懂一带一路,国家智库顶级学者前瞻中国新丝路 [“One Belt and One Road Shows China’s Great Power Attitude”, in Leading Scholars from National Think Tanks and Their Insights on China’s New Silk Road] (Beijing: CITIC Press, 2015).

[12] Dave Boyer, “At White House, Leader of Singapore Urges Congress to Approve Free-trade Deal”, The Washington Times, 2 August 2016, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2016/aug/2/singapore-pm-urges-congress-ok-free-trade-deal/.

[13] Carrie Grace, “US Leaving TPP: A Great News Day for China”, BBC News, 22 November 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-38060980.

[14] Ben Blanchard, “Duterte Aligns Philippines with China, Says US Has Lost”, Reuters, 20 October 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-philippines-idUSKCN12K0AS.

[15] See Johnson, “President Xi Jinping’s ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative”, 20.

[16] Chai Yifei, “三大战略肩负共同使命 [Three Strategies Shoulder the Common Destiny]”, The People’s Daily (overseas edition), 20 September 2016, http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrbhwb/html/2016-09/20/content_1713601.htm.

[17] “Regional Development: Rich Province, Poor Province”, The Economist, 1 October 2016, http://www.economist.com/news/china/21707964-government-struggling-spread-wealth-more-evenly-rich-province-poor-province.

[18] David SG Goodman ed, Handbook of the Politics of China (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015), 198.

[19] The Free Market Index measures Chinese provinces’ degree of economic liberalisation. The Index is published by the China Economic Research Institute.

[20] Wang Xiaolu, Yu Wenjing and Fan Gang, “王小鲁 余静文 樊纲 中国市场化八年进程报告 财经 [A Progress Report on Eight Years of China’s March Towards the Free Market Economy]”, Caijing Magazine, 11 April 2016, 20.

[21] Small, The China–Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics, 69–70.

[22] Alok Ranjan, “The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor: India’s Options”, Institute of Chinese Studies Occasional Paper No 10, May 2015, 12, http://www.icsin.org/uploads/2015/06/05/31e217cf46cab5bd9f15930569843895.pdf.

[23] Lu Shulin, 中巴经济走廊是一带一路的旗舰项目和示范项目 : 张小安 : 中国周边频频起火了吗 [“China–Pakistan Economic Corridor Is the Flagship Project of OBOR”, in Is China’s Neighbourhood on Fire?, Zhang Xiaoan ed] (Beijing: Shijie Zhishi Publishing House, 2016).

[24] Guo Jianwei, 新疆金融业支持‘丝绸之路经济带’战略发展的结构和路径, 读懂一带一路,国家智库顶级学者前瞻中国新丝路 [“Xinjiang’s Financial Services Industry Supports Strategic Development of ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’”, in Leading Scholars from National Think Tanks and Their Insights on China’s New Silk Road] (Beijing: CITIC Press, 2015).

[25] Guan Youqing, 一带一路;第四次投资浪潮来临,读懂一带一路,国家智库顶级学者前瞻中国新丝路 [“One Belt and One Road: The Fourth Wave of Investment”, in Leading Scholars from National Think Tanks and Their Insights on China’s New Silk Road] (Beijing: CITIC Press, 2015).

[26] Arthur Kroeber, “The Never-ending Slowdown”, China Economic Quarterly 19, Nos 3 and 4 (November 2015), 4.

[27] Scott Kennedy, “Made in China 2025”, Critical Questions, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1 June 2015, https://www.csis.org/analysis/made-china-2025.

[28] Dan Breznitz and Michael Murphree, “The Rise of China in Technology Standards: New Norms in Old Institutions”, Research Report Prepared on Behalf of the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission, 16 January 2013, 4, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/RiseofChinainTechnologyStandards.pdf.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Wang Erde, “中国制造2025应于一带一路无缝对接 [The Seamless Integration between Made in China 2025 and One Belt and One Road]”, 21st Century Business Herald, 20 May 2015, http://finance.sina.com/gb/experts/sinacn/20150520/17031264782.html.

[31] Sha Lu, “李克强的 ‘高铁外交’ 成绩单 [Li Keqiang’s ‘High-Speed Rail Diplomacy’ Scorecard]”, Xinhua News Agency, 26 November 2015, http://news.xinhuanet.com/finance/2015-11/26/c_128469565.htm.

[32] “中国制造2025解读之:推进先进轨道交通装备发展 [Interpreting Made in China 2025: Promoting the Development of Advanced Transport Equipment]”, The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, http://www.miit.gov.cn/n11293472/n11293877/n16553775/n16553822/16633922.html.

[33] “China Wins Indonesia High-speed Rail Project as Japan Laments ‘Extremely Regrettable’ U-turn”, South China Morning Post, 29 September 2015, http://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/1862459/china-wins-indonesia-high-speed-rail-project-japan-laments.

[34] Robin Harding and Tom Mitchell, “Rail Battle between China and Japan Rushes Ahead at High Speed”, Financial Times, 20 December 2015.

[35] Cao Zheng, “高铁出海获历史性突破 中国印尼合建雅加达至万隆高铁 [High-speed Rail Export Scores Historical Breakthrough, China and Indonesia Will Jointly Build High Speed Rail between Jakarta and Bandung]”, 17 October 2015, Xinhua News Agency, http://news.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2015-10/17/c_128327911.htm.

[36] Lu Ruquan, “陆如泉,一带一路:油路上的中国 [One Belt and One Road, China On the Oil Road]”, Caixin, 6 July 2015.

[37] Xie Lirong, “移动通信标准翻身战 [Turning the Table on Mobile Telecommunications Standards]”, Caijing Magazine, 7 September 2015, 59.

[38] Hu Huaibang, “胡怀邦:以开发性金融服务‘一带一路’战略, 中国银行业 [Using Development Finance to Serve the OBOR Strategy]”, China Banking, 13 January 2016, http://www.cdb.com.cn/rdzt/gjyw_1/201601/t20160118_2187.html.

[39] World Steel Association data, accessed 8 August 2016, https://www.worldsteel.org/dms/internetDocumentList/statistics-archive/production-archive/steel-archive/steel-monthly/Steel-monthly-2015/document/Steel%20monthly%202015.pdf.

[40] “李克强叩门 ‘新东盟’ 产能合作成重要看点 [Li Keqiang Knocking on the Door of ASEAN Countries and Industrial Capacity Cooperation is the Key]”, Chinese Government Information Portal, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-11/19/content_5014521.htm.

[41] Peter Cai, “Curbs on Coal and Steel will Test Beijing’s Resolve”, The Australian, 19 January 2016, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/business-spectator/curbs-on-coal-and-steel-will-test-beijings-resolve/news-story/43dfa1b17bd88556d1b8746e0c7d2658.

[42] Charles Clover and Lucy Hornsby, “China’s Great Game: Road to a New Empire”, Financial Times, 13 October 2015.

[43] Li Keqiang’s Official Speech at the 17th ASEAN–China (10+1) Leaders’ Meeting, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 13 November 2014, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/ziliao_674904/zt_674979/dnzt_674981/qtzt/ydyl_675049/zyxw_675051/t1210820.shtml.

[44] Hu Huaibang, “以开发性金融服务‘一带一路’战略 [Using Development Finance to Service the One Belt and One Road Strategy]”, first published in China Banking Industry Magazine, 13 January 2016, http://www.cdb.com.cn/rdzt/gjyw_1/201601/t20160118_2187.html.

[45] Jin Qi’s speech in Hong Kong on 18 May 2016 at Belt and Road Summit, http://www.silkroadfund.com.cn/cnweb/19930/19938/32726/index.html.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Interview with a senior economic official from Hubei province, August 2016.

[48] “我省力推钢铁水泥玻璃过剩产能向境外转移, 河北省人民政府 [Hebei Province Promotes the Migration of Excess Capacities from Steel, Cement and Pleat Glass Sectors]”, Policy Directive from Hebei Provincial Government, http://www.hebei.gov.cn/hebei/11937442/10761139/12224328/index.html.

[49] Liu Xiao, Wang Xu and Wang ShuQin, 一带一路的愿景与行动,读懂一带一路,国家智库顶级学者前瞻中国新丝路 [“One Belt and One Road: The Vision and Implementation”, in Leading Scholars from National Think Tanks and Their Insights on China’s New Silk Road] (Beijing: CITIC Press, 2015), 169.

[50] Zheng Xinli, “在海外投資的方向与战术 [The Directions and Tactics in Investing Overseas]”, in 一带一路 金融大战略 [One Belt and One Road and the Grand Financial Strategy], Chen Yuan and Qian Yingyi eds (Beijing: CITIC Press, 2016), 76.

[51] “习近平在推进 ‘一带一路’ 建设工作座谈会上发表重要讲话 张高丽主持, 新华社 [Xi Jinping’s Speech at the One Belt and One Road Work Conference, Chaired by Zhang Gaoli]”, Xinhua News Agency, 17 August 2016, http://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2016-08/17/content_5100177.htm.

[52] Tanvi Madan, “What India Thinks about China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative (But Does Not Explicitly Say)”, Order from Chaos (blog), Brookings Institution, 14 March 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2016/03/14/what-india-thinks-about-chinas-one-belt-one-road-initiative-but-doesnt-explicitly-say/.

[53] Interview with Sameer Patil, Mumbai, India, August 2016.

[54] Kamran Haider and Ismail Dilawar, “Militants Strike Pakistan, Hitting China’s Economic Corridor”, Bloomberg, 26 October 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-10-25/militants-return-to-pakistan-hitting-china-s-economic-corridor.

[55] “国开行建立900余 ‘一带一路’ 项目库 涉资金近万亿美元 [China Development Bank Builds One Belt One Road Project Bank and the Total Amount is Approaching One Trillion USD]”, Caijing, 28 May 2015, http://m.caijing.com.cn/api/show?contentid=3893051.

[56] Huo Yu, Wang Ling and Wu Hong Yu Ran, “一带一路会是海外的4万亿吗 [Will One Belt and One Road Become the Overseas Version of the Wasted Four Trillion Stimulus]”, Caixin Weekly, 15 June 2015.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Email interview with Andrew Collier, Managing Director of Orient Capital Research, October 2016.

[59] Interview with a senior Chinese financier, Beijing, June 2016.

[60] Huo Yu, Wang Ling and Wu Hong Yu Ran, “[Will One Belt and One Road Become the Overseas Version of the Wasted Four Trillion Stimulus]”.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Huang Yiping, 一带一路战略下的对外投资新格局,读懂一带一路,国家智库顶级学者前瞻中国新丝路 [“New Overseas Investment Landscape against the Backdrop of One Belt and One Road Strategy”, in Leading Scholars from National Think Tanks and Their Insights on China’s New Silk Road] (Beijing: CITIC Press, 2015), 138, 285.

[63] Ibid.

[64] “Thailand Rebuffs Railway Deal with China”, The Straits Times, 5 May 2016, http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/thailand-rebuffs-railway-deal-with-china.

About the author

Peter Cai is a Nonresident Fellow at the Lowy Institute for International Policy. Previously he was a journalist with The Australian, Business Spectator, The Age and Sydney Morning Herald, covering business and economic news. Prior to becoming a journalist, Peter was at the Australian Treasury where he worked in the Foreign Investment Review Board Secretariat, focusing largely on state-owned enterprises and sovereign wealth fund investment policy. Peter has a master’s degree from Oxford University and holds undergraduate degrees from The University of Adelaide.