During a summer break, The Interpreter will feature selected articles each day from throughout the past year. Normal publishing will resume 15 January, 2024. This article first appeared on 6 June, 2023.

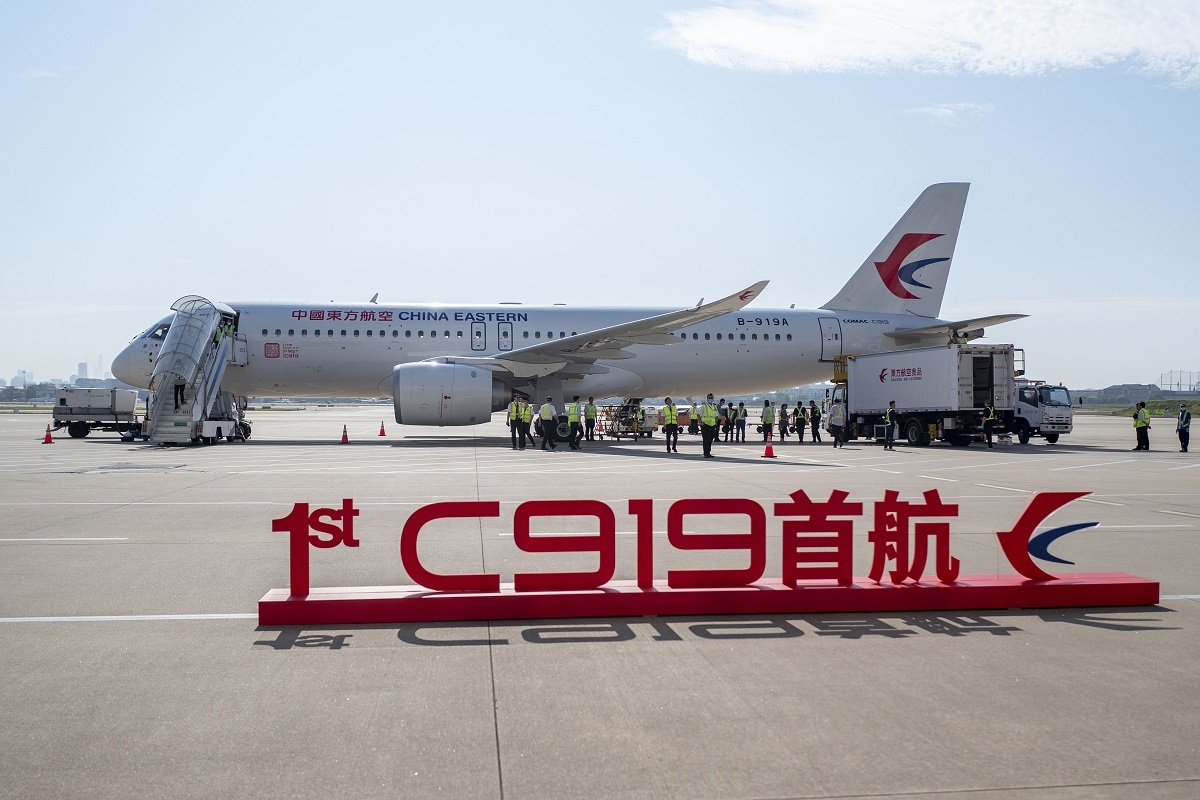

Late May 2023 marked the inaugural commercial flight of China’s first homegrown jet airliner, the COMAC C919. In a carefully planned symbolic event, China Eastern Airlines flight MU9191 took off from Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport – where US President Richard Nixon first arrived during his tour of China in 1972 – and landed in Beijing, the mainland’s capital.

Touted as Beijing’s response to the American Boeing 737 and the European Airbus A320 families, the twin-aisle regional jet aims to cater to the Chinese domestic market and the prospective Asian market. Although the flight was marketed by Beijing as evidence of China’s achievements in aviation technology, it also sparked debates about the incorporation of American components and allegations of intellectual property theft in the design and construction of the COMAC aircraft. Nevertheless, the C919 is the newest tool in Chinese foreign policy, much like the DC-3 revolutionised US President Roosevelt's aviation diplomacy.

Perhaps no other plane shaped post-Second World War international aviation politics more than the DC-3. Renowned as the backbone of logistics during the war, it was also among the first passenger-only commercial airliners. It boasted a long range with comfortable seating – for its time, at least – which allowed it to operate passenger flights without relying on freight mail to keep it profitable.

US President Franklin D. Roosevelt actively recognised the DC-3 as a valuable tool for enhancing US foreign relations. Roosevelt proudly showcased American aviation technology on his trips abroad, utilising his presidential C-54 Skymaster, affectionately known as the Sacred Cow, and a fleet of DC-3s, as a symbol of American ingenuity and prestige.

Roosevelt also presented DC-3 aircraft as gifts to strategically important states. The most notable instance was to King Abdul Aziz of Saudi Arabia, symbolising diplomacy and friendship after Roosevelt’s historic meeting with the King along the Suez Canal on 14 February 1945. Just six years later, the two countries signed the 1951 Mutual Defence Assistance Agreement, a formal defence pact that cemented the two states’ close relationship. The DC-3 also marked the birth of Saudia, the flag carrier airline of Saudi Arabia.

China’s new C919 holds similar potential for President Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, offering striking parallels to Roosevelt’s use of American DC-3s. The C919 carries symbolic value for China’s foray into great power politics vis-à-vis international aviation. Xi no doubt aims to leverage the C919 to strengthen diplomatic ties and promote Beijing’s global influence.

Currently, only regional Chinese airlines have ordered the C919, intending to use them for short, domestic routes. For Beijing to parade the aircraft as a technological success and symbol of prestige internationally, the C919 needs to be operated by airlines beyond the Chinese mainland. Here, state-owned airlines may prove more amenable than private operators to Xi’s persuasion, as the former align closely with a government’s policies rather than the whims of for-profit shareholders. In particular, the C919 can gain legitimacy if Xi targets two specific groups of potential C919 operators in his diplomatic efforts over the next decade.

The first group comprises Chinese partners facing broad international sanctions, including Russia, Iran and North Korea. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has scourged the Russian civil aviation sector with sanctions, no-fly zones and aircraft impounds. Iran’s commercial aviation sector has suffered due to years of conflict, poor infrastructure, neglect and under-investment. International sanctions have made it nearly impossible to purchase aircraft parts, let alone new aircraft. North Korea faces the same issues, with its leader Kim Jong-un borrowing an American-made Air China Boeing 747 to travel to Singapore for the Trump-Kim summit in June 2018. The C919 may present an opportunity for Beijing to breathe new life into the aviation sectors of Iran, Russia and North Korea.

The second group comprises emerging players in the international arena that Beijing hopes to include in its sphere of influence. An Indonesian airline, TransNusa, has already shown interest by purchasing the smaller Chinese jet airliner, the ARJ21. Other Indonesian carriers, including its flag carrier Garuda Indonesia, may also be persuaded to invest in Chinese aviation technology. Emerging powers, such as India, which manufactures aeroplane parts, may be enticed to shift away from Western aircraft for the sake of having Asian-made planes for Asians. Kenya and Ethiopia have already embraced Chinese railway infrastructure and may be receptive to expanding their reliance into aviation technology.

However, the C919 is unlikely to break the Boeing-Airbus duopoly. The two largest manufacturers of commercial jets after Airbus and Boeing – Brazil’s Embraer and Canada’s Bombardier – struggle to compete on their own, with Bombardier recently selling its CSeries family to Airbus. Russia’s Ilyushin serves mainly ex-Soviet markets, and Japan’s Mitsubishi SpaceJet remains indefinitely shelved.

For Xi to mirror the transformative influence of Roosevelt’s DC-3 in foreign policy, he must use the C919 as a tool to gain the confidence of foreign leaders and their airlines. Beijing needs to address concerns about safety, reliability and performance while ensuring the aircraft’s price is competitive against Western-made planes. There is no doubt that over the next decade, aviation diplomacy in Asia will become yet another arena of competition between the two superpowers.