Next week, members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations will commence joint military exercises, officially called ASEAN Solidarity Exercise Natuna (ASEX 01–Natuna), around Batam Island at the eastern approaches of the Malacca Strait. Taking place from 18–23 September, the primarily maritime exercises will involve regional navies, armies and air forces. They will focus on maritime security, disaster response, and rescue operations rather than combat exercises. As a bloc, ASEAN has previously conducted joint exercises with other countries, including the United States and China, but this is the first time such drills will be a member-only affair.

Announced at the 20th ASEAN Chief of Defence Forces Meeting in Bali in early June this year, the exercises were originally planned for the southern part of the South China Sea – an area where Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone overlaps with China’s “nine-dash line” – but have since been moved to within Indonesia’s archipelagic waters in the South Natuna Sea. Reports suggest this was due to sensitivities surrounding disputed claims between several ASEAN countries and China, with some indicating the change was made at Cambodia’s behest. Indonesia’s military has denied this was the result of external pressure, saying the change was made because the new location is more suited to the non-combat nature of the drills, with priority “given to areas that are prone to disasters”.

While some analysts view the location change as a missed opportunity for ASEAN to challenge China’s “nine-dash line”, the exercises have nevertheless been interpreted as a demonstration of unity at a time of perceived ASEAN stagnation amid continued Chinese assertiveness. When announcing the drills, Chief of Indonesian National Armed Forces Admiral Yudo Margono stated that “It is about ASEAN centrality." This is a view shared among experts, who see the exercises as “strengthen[ing] the ASEAN concept of an Indo-Pacific outlook” by focusing on maritime issues such as “countering piracy, sea accidents, pollution, and search and rescue”.

Perhaps most notably, the fact that Southeast Asian countries have chosen joint maritime exercises as a platform to explicitly reaffirm ASEAN centrality is indicative of the importance that the region ascribes to maritime issues.

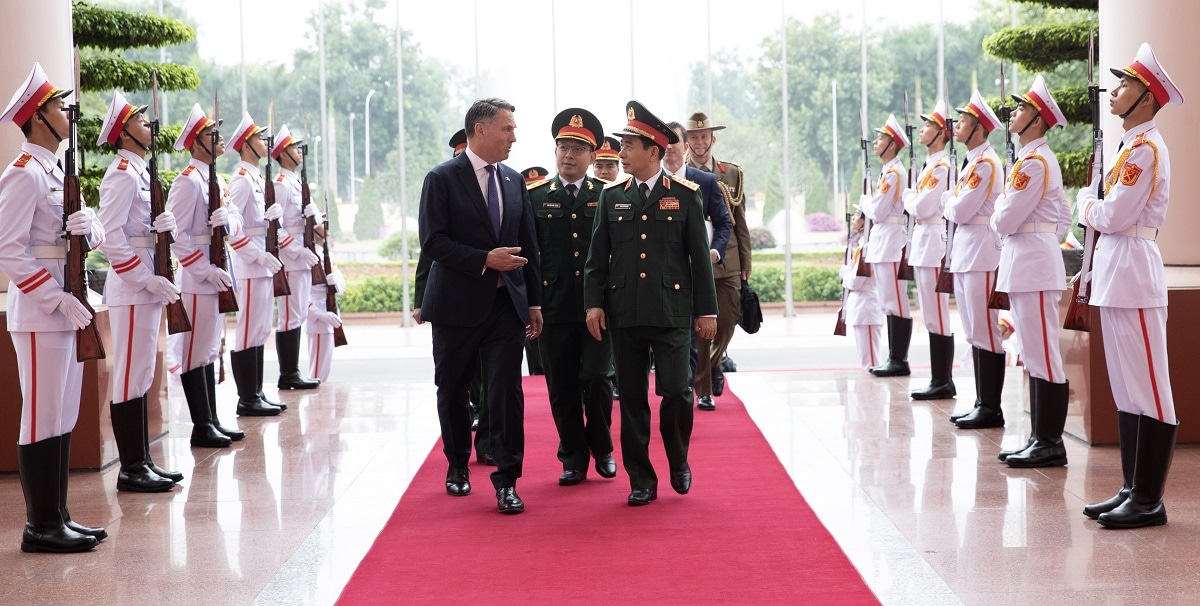

Like many countries, ASEAN centrality is a pillar of Australia‘s engagement with the region, the significance of which is enshrined in key documents such as the International Development Policy, Foreign Policy White Paper and Defence Strategic Review. These all outline in different ways why and how Australia’s own security is enmeshed with that of Southeast Asia’s. This position is reinforced through ministerial speeches, with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Richard Marles, and Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong all emphasising a need to shape a shared future together with the region.

If these commitments are to ring true, Australia needs to listen to and help address regional priorities. Just because Canberra isn’t taking part in ASEAN Solidarity Exercise Natuna doesn’t mean it can’t contribute to the same overarching goal of enhancing ASEAN centrality through maritime security. To that end, what types of things can and should Australia do?

Noting their shared interest in and mutual benefits of a stable maritime environment, a recent report – borne out of consultations with 45 experts from across the region – explores how Australia and Southeast Asia can develop a joint agenda for maritime security. It outlines a vision where Australia “bring[s] all the elements of statecraft together to meet the maritime security challenges facing Southeast Asia”, and offers several pathways by which this can be realised.

These include capitalising on Australia’s experience and reputation as a provider of military maritime capacity-building programs by extending training to both civilian and government officials in Southeast Asian countries, and through the expansion of English training programs to overcome barriers and pave the way for deeper collaboration between defence agencies. The Australia Awards and ASEAN-Australia Defence Postgraduate Scholarship Program are both mechanisms that can be expanded and utilised not just for technical training and operational knowledge, but to develop strategic thinking.

Australia is also well placed to support regional maritime domain awareness (MDA) through increased information sharing and joint analysis to allow countries to react faster to incidents and set regional priorities. This can be achieved through building on existing agreements and arrangements, including with the regional Information Fusion Centre in Singapore. Australia’s experience supporting MDA, maritime security and infrastructure development across the Pacific provides valuable lessons.

The Australian government can also work with Southeast Asian partners to establish an agreed Single Point of Contact (SPOC), or lead agency, for maritime security in each country that is able to transmit information at the national level. SPOCs can be a cost-effective solution to disseminate and share information, discuss challenges and develop proposals, and can be implemented with few administrative, legal or diplomatic hurdles.

Finally, Australia can take a long-term generational approach to maritime security issues and support youth engagement as a way to use soft diplomacy to train the next generation of ASEAN and Australian leaders, foster cooperation, and develop innovative security strategies. The successful ASEAN-Australia emerging leaders’ program, which brings together social entrepreneurs from Australia and ASEAN member nations, could be expanded – and could be given a maritime security focus in one of the years in which it is held.

There is much to be said of the value of Australia participating in joint exercises with regional partners, but sometimes the less flashy options can be equally as effective. Regardless of whether Australia is invited to participate in future joint exercises with ASEAN, it should continue to take a broad approach to strengthening regional maritime security. If Australia and Southeast Asia are to develop a joint agenda for maritime security, the bloc’s first member-only joint exercises and Canberra’s own efforts should be seen as two sides of the same coin.

This article draws on the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue (AP4D) paper What does it look like for Australia and Southeast Asia to develop a joint agenda for maritime security, produced as part of the Blue Security program. AP4D thanks all those involved in consultations.