Reports of Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili’s recent visit to China and his meeting with President Xi Jinping suggest that Beijing remains interested in the Middle Corridor.

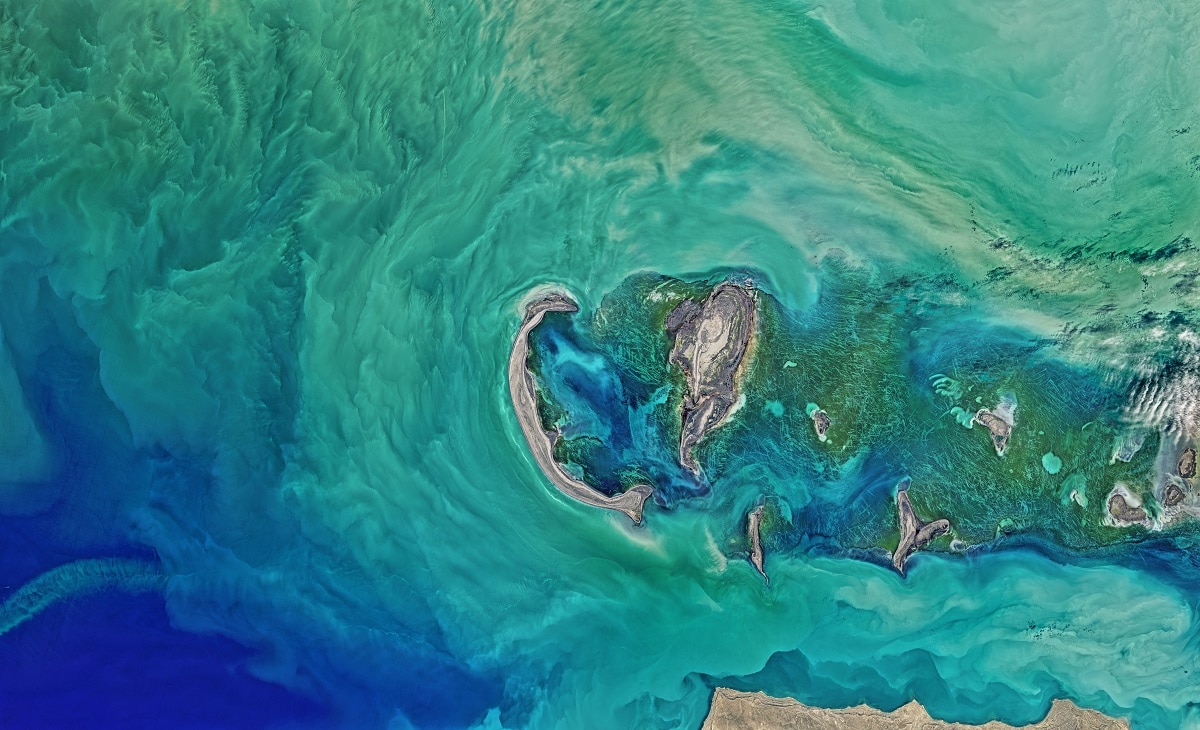

The Middle Corridor, also known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, is an extensive multi-modal infrastructure network of interconnected routes – ferry, port, railway, and road – linking China to Europe through Central Asia, the Caspian Sea and the South Caucasus (Georgia and Azerbaijan). From there, cargo travels via Türkiye or the Black Sea before reaching the European Union, thereby bypassing Russia and Iran. The route comprises more than 4,250 kilometres of rail lines and 500 kilometres of seaway.

The Middle Corridor could reduce transit time between China and Europe to 12 days, in comparison to the current 19-day journey via the overland Russian-dominated Northern Corridor or 22 to 37 days via the maritime Southern Corridor.

The Corridor was first proposed in the late 2000s by Türkiye as part of broader efforts to improve Ankara’s strategic position in the region. In 2020, following the Trans-Kazakhstan railway’s 2014 opening and the completion of the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway (from the Caucasus to Türkiye) in 2017, the first train travelled from Türkiye along the Middle Corridor to China.

Interest has continued to grow since, in part due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions on Russia and Belarus. Before the war, the Russian-dominated Northern Corridor used to carry more than 90 per cent of rail cargo between Europe and the Far East. As transporting goods across Russia has become more difficult, the Northern Corridor’s shipping volume has decreased by 40 per cent.

With China and other countries interested in establishing stable, alternative overland trade routes to avoid transiting through Russia, cargo travelling along the Middle Corridor has skyrocketed from 350,000 tons in 2020 to 3.2 million tons in 2022.

Beijing hasn’t trumpeted its interest in this new route compared to its public enthusiasm about other connectivity projects. But meetings between Ankara and Beijing both last year and this year have continued to acknowledge the synergy between China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Turkey’s Middle Corridor.

For Beijing, the Middle Corridor offers numerous benefits. Notably, it can help decrease China’s reliance on existing routes, thereby reducing the risk of disruptions, such as economic coercion, to trade flows.

The Corridor could lead to greater Chinese influence and regional integration in Central Asia, where competition for influence between Moscow (the regional hegemon), Beijing, and Ankara (albeit the latter to a lesser extent) is centred. Russia has not wanted to lose influence in the region or upset the current balance of power in either Sino-Russian relations or in Central Asia. From Moscow’s perspective, this could result in growing Chinese investment in Central Asia and potentially make the region more dependent on China.

Moscow has sought to bolster its position by strengthening Russian-centric regional economic integration frameworks, such as the Eurasian Economic Union. Still, Russia’s attention appears diverted by the conflict in Ukraine. Beijing may seek to capitalise on this by using the Middle Corridor and broader efforts for regional connectivity and economic cooperation to reshape the regional geopolitical landscape to China’s advantage.

The potential for increased trade between China, Central Asia, and Europe should also be considered. The Middle Corridor helps give Chinese exports greater access to markets in Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. Reduced transportation times and costs will make Chinese exports more competitive.

Aside from strengthening inter- and intra-regional trade, including through planned bilateral investment agreements and various infrastructure projects, Beijing’s interest in the Middle Corridor could result in stronger economic growth and job opportunities in participating countries. This, in turn, offers opportunities for Chinese construction companies, which face overcapacity at home.

There are some challenges. Aside from factors such as the difficult climate conditions around the Caspian Sea, the issues of regional security and the absence of institutional frameworks and adequate infrastructure must also be addressed.

While a stable environment is essential to making the Corridor a durable alternative, a complex array of national, ethnic, and regional (geo)political tensions and related issues continue to influence surrounding areas. Reports of weapons smuggling from Ukraine to the South Caucasus further raise fears of instability moving across borders.

Dealing with competing, fragmented interests, including from Türkiye, Russia, Iran, and the West, across different regions is another challenge. A new railway line announced by Russian President Vladimir Putin that will connect Iran along the North-South Transport Corridor – a multi-modal route that links India to Russia and Northern Europe via Iran and Azerbaijan – has the potential to compete against the Middle Corridor.

Even with a significant increase in cargo volume, the Middle Corridor still represents less than ten per cent of the total cargo transported via the Russian-dominated Northern Route. It is also much less than the enormous one billion tons of cargo that the maritime Southern Route is expected to carry this year.

Making matters more complicated are difficult geography and terrain, logistical issues and the lack of adequate infrastructure. In response, some participating countries are already seeking to expand their cargo capacity and relevant infrastructure. Azerbaijan, for instance, aims to increase the Baku International Sea Port’s cargo capacity, while Georgia plans to build a deep-sea port at Anaklia.

Elsewhere, Kazakhstan plans to create multi-functional terminals and a container hub at one of its busiest ports, following China’s construction of a large rail trans-shipment centre on the Kazakhstan-China border.

Other recent movements, including a Caspian Sea multi-modal agreement and the signing of “roadmaps” to improve the efficiency of the trade route, suggest that such developments will continue to increase.

Although the Middle Corridor offers all participating countries, particularly China, many geopolitical and geoeconomic opportunities, significant obstacles must be overcome to achieve its full potential.