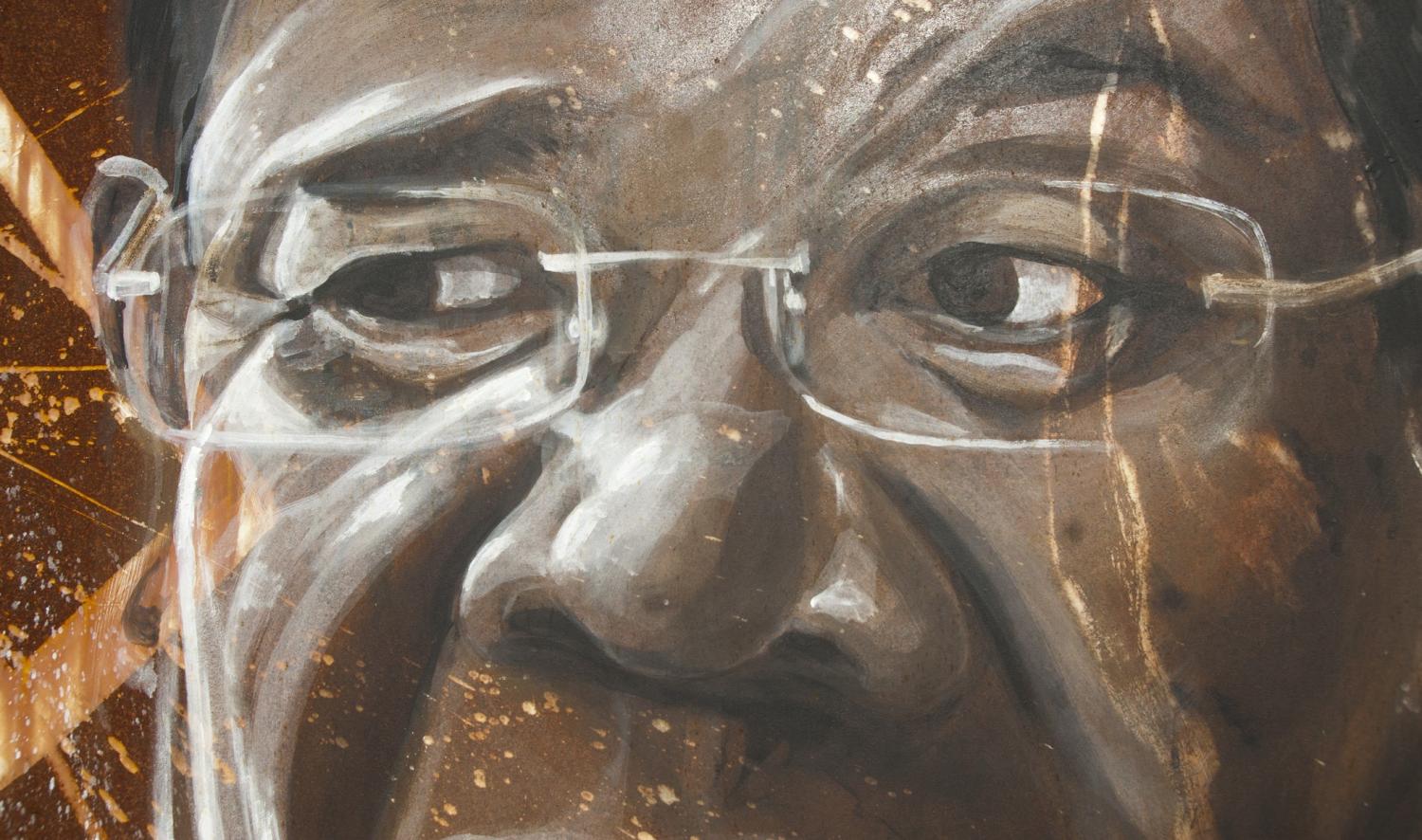

After 32 years at the helm, Cambodia’s Hun Sen will effectively be running uncontested at next year’s elections. The world’s longest reigning prime minister has abolished the opposition in his country and realised a dream to do away with a UN imposed democratic system he has long despised.

Hun Sen last month used his courts to dissolve the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party, drawing condemnation from Western nations but to little effect. His move underscores the failure of a UN operation in Cambodia that began in the 1990s, then the largest and most complex international intervention ever attempted.

For Hun Sen, it was a worthwhile gamble to remove a dangerously powerful opposition that had polled above 40% in two successive previous elections. But it was also a way to loudly declare he no longer needed to tolerate decades of hypocritical western lecturing. Hun Sen has a trove of material to work with and the brunt of the invective from him and his PR machine has been directed squarely at the US – everything thing from the blatant nepotism of Donald Trump, to US support of the murderous Khmer Rouge in the 1980s, or the Pentagon’s secret carpet bombing of Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

Hubris is catching up with America and after more than half a century of preaching democratic idealism while showing regular disregard for those values in the execution its foreign policy, skeletons are being dragged out of the closet by autocrats across Asia.

Yet Hun Sen’s performance of victimization is far from convincing.

Hun Sen has been more than happy to take billions in aid from the US, European Union, Japan, Canada and Australia, largely funding critical social services while he solidified his power via a sprawling network of deputised cronies. In return, however, these donors exact a price, funding organisations that apply the kind of scrutiny to his rampantly corrupt patronage network that causes Hun Sen ‘Chu K’bal’ - headaches.

Some of these organisations, as he alleges, undoubtedly have been used as policy tools in US strategic meddling. But most are guilty of simply doing their jobs. After decades of reluctantly tolerating civil society Hun Sen now believes he can have a purely transactional relationship with the West in which they open their markets and pour aid dollars into his country no matter how despotic and abusive his behaviour.

Publically, Hun Sen has brushed off threats of aid withdrawal and sanctions as irrelevant, confident in the financial support he now enjoys from wealthy benefactors in Beijing. But the idea China will simply indefinitely bankroll Cambodia’s hopelessly undiversified economy if Hun Sen blows all his country’s relationships with the West is somewhat wishful.

Feeling the pinch

A leaked recording of Hun Sen published in The Phnom Penh Post last week revealed he did indeed privately harbour concerns about international repercussions. Calling his bluff with punitive actions could send ripples of discontent through his labyrinthine patronage network, even if sanctions have proved unpredictable mechanisms in the past and have plenty of detractors.

A 2013 study by a group of academics called the Targeted Sanctions Consortium found such measures achieved only one of their goals in 22 percent of cases, findings consistent with the broader body of research on this topic. Often the sanctions had unintended consequences including increases in corruption and damage to the credibility of the UN itself.

UN sanctions won't be imposed on Cambodia thanks to the Security Council veto power of Russia and China. But sanctions have already been threatened by both the US and EU, which absorb the vast majority of Cambodian exports. China, by contrast, takes practically none.

Trade sanctions are controversial because they generally hit the lowest wage earners in the country the hardest. For example, sanctions imposed on the Burmese junta at the turn of the century devastated the fledgling garment industry yet achieved none of the political aims. But in Cambodia it is a very different picture. Some 600,000 people are formally employed in the garment industry. Alternate employment opportunities are so scarce that more than one million people - close to 10% of the entire population - have migrated to Thailand for work despite recurring tales of brutal migrant workers exploitation in the neighbouring country.

Trade sanctions would have dramatic political implications, pushing thousands of angry workers onto the streets with likely knock on effects into tourism, banking and foreign investment. Given that some 65% of the garment factories in Cambodia are Chinese owned, garment sanctions might drag in pressure from unexpected quarters as well.

The right target

But no one wants to put more than half a million people out of work, especially in a country that has been through decades of almost unending tragedy. A number of analysts also argue such actions would just push Hun Sen closer to China, although how Cambodia could slide any further into Beijing’s orbit than it already is unclear. Aid withdrawals – already announced by the US and Sweden - and targeted sanctions might be the best bet for the original backers of the 1990s UN mission at this stage, even if their track record is patchy.

Cambodia’s vast political class have developed a luxurious palate for international travel and goods while sending their children to elite schools in the US and Europe. Many have also extensive family networks in the US, Canada, Australia and France. Asset freezing probably comes too late to have any real effect but restrictions on financing and doing business with US companies could certainly sew some disharmony among the oligarchy - more Chu K’bal headaches for Hun Sen.

Taking that kind of action could cost Western powers a seat at Hun Sen’s negotiating table, but when he consistently shows a total disregard for their interests at what point does the cost of that seat outweigh any perceived benefit? There are no obvious options for the West to halt Cambodia’s slide in outright authoritarianism.

Yet to stand by and do nothing as Hun Sen makes a mockery of the political system while he bites the hands that have long fed him must not only feel humiliating but a betrayal of the ideals imposed on Cambodia back in 1993.