Back to basics

When the International Monetary Fund kicked off its latest twice-yearly meetings with blunt criticism of the fiscal policies of the new British government it seemed like yet another step on the path from neo-liberal tough medicine to more activist developmentalism.

Here was one of the spear carriers of market-driven globalisation telling the world’s sixth biggest economy that its experiment in 1980s-style trickle-down economics “will likely increase inequality”.

The move sparked some contrasting reactions, with former US Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers saying it showed how the IMF should no longer discriminate between its founding rich country and rising emerging market shareholders. But former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis said that while this looked like “the janitor scolding the landlord” it was more about the IMF panicking rather than embracing social democracy.

Nevertheless, as the world’s economic policymakers faced up to uncertainties more akin to the 2008 global financial crisis than the pandemic of recent times, it was hard to ignore how much the public face of the financial watchdog has changed. The IMF annual report Crisis Upon Crisis declares: “Working together is the only way we can successfully address the challenges we face. Our member countries can count on us to nurture collective action for a strong and inclusive economy.”

So in its Global Financial Stability Report the IMF backs a crackdown on open-ended investment funds, a key feature of globalisation from an investor perspective. The World Economic Outlook (WEO) warns countries against putting off collective climate change action because of the longer term costs. Over at the World Bank, the latest Poverty and Shared Prosperity report calls for broad tax increases to deal with the consequences of the end of three decades of global income convergence.

It is hard to know how many people actually read the semi-annual deluge of research ideas, but this does seem to be to be a case where trickle-down economics works with the themes shaping the international economic orthodoxy. And despite Varoufakis’ scepticism they are distinctly from a new school of interventionism.

But that only underlines the contrast with the actual outcomes from one of the biggest gatherings of the global economic elite since the pandemic. Firstly, when it comes to dealing with inflation and the associated relentless rise of the US dollar, the IMF econocrats have essentially reverted to old-style thinking. Here’s the boilerplate response from first deputy managing director Gita Gopinath and economic counsellor Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas:

“Given the significant role of fundamental drivers, the appropriate response is to allow the exchange rate to adjust, while using monetary policy to keep inflation close to its target.”

Of course, these paid officials can’t conjure up another Plaza currency accord between the major economic powers by themselves, but this retreat to basics comes after all the research about rising developing country debt burdens, a food crisis and a big reversal in poverty reduction.

Secondly, despite the “crisis upon crisis” theme of the annual report, repeated by various top officials, the week has ended with considerably less confidence that the Group of 20 countries can work collectively as they did in 2008–09. The former IMF official Mohamed El-Erian has observed that the mood last week was as grim as 2008 but the lack of collective spirit compared with that time meant countries were being left to their own resources with “a sub-optimal outcome for them and the world as a whole”. And former United States trade negotiator Wendy Cutler told an Asia Society Australia event in Sydney this week the IMF meetings had been “more of a blame game than a roadmap for cooperation.”

Of course, the central bank unity over interest rate cutting in 2008 was followed by arguments between countries about how to do the needed fiscal stimulus and then the undue reliance on quantitative easing for years to follow. But while Australia’s Treasurer Jim Chalmers might have been more front footed than his mentor and former boss Wayne Swan during the 2008 crisis by suggesting during his Washington visit that the US Federal Reserve Board should hasten slowly on its interest rate rises, he looks much more alone than Swan was in dealing with the consequences of all this uncertainty in next week’s budget.

Dollar Joe

While he clearly has a currency market tailwind, US President Joe Biden showed a bit of geopolitical tone deafness this week with his blithe dismissal of the pressures which the rising greenback is imposing on much of the rest of the world.

“I’m not concerned about the strength of the dollar, I’m concerned about the rest of the world. Our economy is strong as hell,” Biden told an election campaign event as the IMF/World Bank crowd tried to guess where the next currency stress would occur. And the choices are remarkably diverse, from close US ally Japan where the yen is down more than 20 per cent since June, or occasional partner Turkey where the lira is down more than 30 per cent.

While this crisis is yet again showing the dollar’s perverse attraction as a safe haven regardless of American domestic politics, it is nevertheless also a core geopolitical asset facing speculation about alternatives ranging from Bitcoin, to gold, to the Chinese currency. Those alternatives mostly don’t look attractive these days, but lingering resentment is likely to remain around the world about the extent that poor monetary management by the US Federal Reserve has transferred the main hardship to the developing world.

So rather than just dismiss the global pain caused by American control of the global reserve currency, Biden could have at least acknowledged the situation and lent some lip service to the concerns being discussed at the IMF meetings. For example, the US shareholder veto in the IMF and the World Bank means it has an outsized influence over the discussion about getting more lending leverage out of multilateral development bank capital.

One of the most important shifts in the global economy has been the shift of the US from being a large energy importer to one that is basically self sufficient (ht @Brad_Setser on the chart) pic.twitter.com/fphb8RJmrq

— Bob Elliott (@BobEUnlimited) October 5, 2022

The world is overflowing with geo-economic charts at this time of the year but this one provides quite an insight into current Bidenesque American exceptionalism. It shows how the United States’ shift towards energy self-sufficiency insulates it from the Ukraine war energy pain in Europe and East Asia, and along the way likely stiffens its enthusiasm for new National Security Strategy of taking on Russia and China at the same time. And, on top of that, ironically much of the non-US energy exporter revenue – like the Saudis’ windfall gains – winds up in rising US dollar assets.

Collateral damage

One of the reasons why the ability of the IMF and World Bank to chart a path through the current geopolitical shoals is important is because of what it will say about their ability to function in a decoupled world.

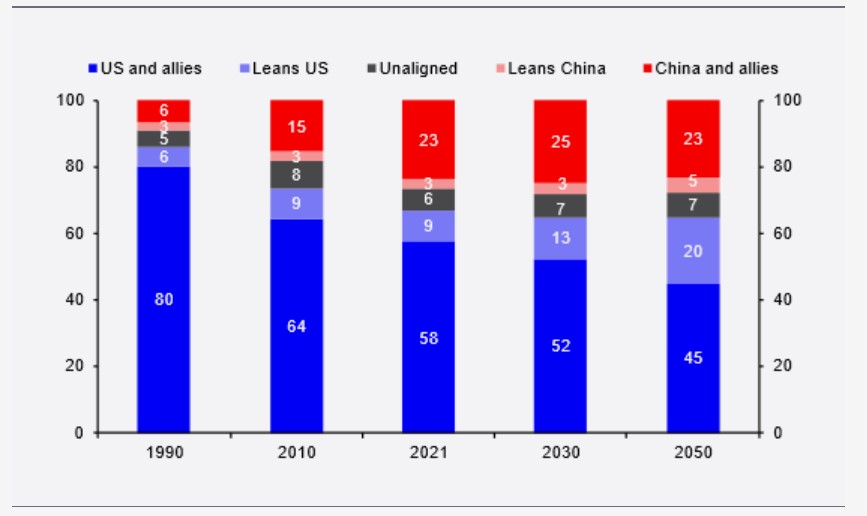

A new study by Capital Economics The Fracturing of the Global Economy takes a relatively benign view of what the decoupling of the United States and China – implicit in the Biden administration’s new semi-conductor rules – means for members of what it calls the US-aligned bloc. It sees this bloc as quite balanced in terms of assets and skills and access to the powerful US dollar financial plumbing, including the US dollar. Nevertheless, this assumes a gentle decoupling over time.

The shape of a divided world (%)

But it raises significant concerns about how global economic policy “anchors” or institutions from the IMF to the World Trade Organization (WTO) will be hollowed out as policy makers or coordinators. It is uncertain about whether they will be variously subsumed by the blocs or be replaced by bilateral/regional agreements/institutions which reflect the blocs. It notes this has already happened in the WTO where the United States has undermined the appeals system:

“While this hasn’t been an economic disaster – and the institution had been effectively side-lined anyway – it is symptomatic of the move away from global policy coordination.”

In contrast to the thinking at the IMF/World Bank last week, the report argues that the global pandemic spending was larger than the global financial crisis spending but occurred more organically with less coordination, so the bifurcated world might still get by on this front.

It argues the main losers will be developing countries which have benefitted from the policy reform or development anchors provided by the Bretton Woods institutions over more than half a century. And so:

“In a world in which the power of global economic institutions has waned, the biggest effects are likely to be felt in those emerging markets in which there is still ample scope for market liberalisation to increase productivity.”

The report also points out that many of the countries it defines as being within the China bloc are still quite dependent on Bretton Woods institution assistance or support but would likely be forced to turn more to China.

As a self-declared member of the US bloc but a development aid provider to a number of neighbouring countries quite aligned to China, Australia would find itself in a tricky situation in this fractured world.

Middling along

There’s not much good news in newly invigorated global institutions being stalemated by global politics and rich countries transferring their monetary policy mismanagement to poor countries. But one of the positive themes in the IMF/World Bank reports is the relative confidence that some of the large emerging markets – which could play a more important role in a decoupled world – are navigating the crisis reasonably well.

The WEO notes that some larger middle income emerging markets countries are better positioned to deal with rising debt than the smaller, poorer countries which reflects the way they have built up bigger reserves and deeper local capital markets than in past global crises.

And the World Bank’s poverty report points out that despite the pandemic India managed to use digital cash transfers to provide food or cash support to 85 per cent of rural households and 69 per cent of urban households. South Africa also embarked on its biggest expansion of a social safety net in a generation by spending US$6 billion on poverty relief for 29 million citizens. And Brazil reduced extreme poverty despite an economic contraction by using a family-based digital cash-transfer system.

But this requires the capacity to target cash transfers with new digital tools that the poorer countries don’t have.