An end-of-year series as the Lowy Institute staff and Interpreter contributors offer their favourite books, articles, films or TV programs this year. Look back on the series and watch for more recommendations and reflections in the days ahead.

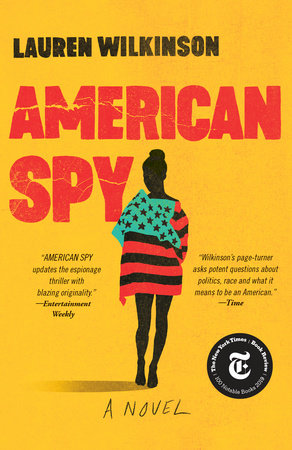

Like the best spy novels, Lauren Wilkinson’s American Spy plays with the moral ambiguity associated with intelligence gathering. But this book stands out as my favourite of 2020 because Wilkinson elevates the genre with a Black female protagonist.

The story centres on Marie Mitchell, a young FBI agent who is recruited by the CIA in the late 1980s to spy on Thomas Sakara, the (real-life) charismatic leader of the newly born Burkina Faso, whose communist ideology made him a target for American intervention. The book opens with an attempt on Mitchell’s life, and the plot moves along quickly, alternating between Mitchell’s childhood in 1960s, her career as an FBI agent in the late 1980s and her escape to her mother’s home on the island of Martinique with her two four-year-old sons in 1992.

The story centres on Marie Mitchell, a young FBI agent who is recruited by the CIA in the late 1980s to spy on Thomas Sakara, the (real-life) charismatic leader of the newly born Burkina Faso, whose communist ideology made him a target for American intervention. The book opens with an attempt on Mitchell’s life, and the plot moves along quickly, alternating between Mitchell’s childhood in 1960s, her career as an FBI agent in the late 1980s and her escape to her mother’s home on the island of Martinique with her two four-year-old sons in 1992.

Mitchell tells the story through the frame of a letter to her young sons, in the event that she doesn’t survive the next attempt on her life. There’s romance and danger and extended conversations between an undercover Mitchell and Sakara on communism and how Black men such as Mitchell’s law enforcement father could serve a country that treats them like second-class citizens.

Mitchell fits the mould of the male spies who dominate the genre: she’s a loner and a competent liar capable of violence and willing to make some compromises to advance professionally. But Mitchell’s character also demonstrates a high level of self-awareness that I found satisfying and comforting this year. As a mother, she finds the words to explain how she, and those that came before her, survived and advanced and lived with their choices.

In the letter to her sons, Mitchell acknowledges that some of what she has told them will be difficult to parse:

One thing I can say for sure is that I don’t want you to be moral absolutists. If what I’m telling you of our story means to you that the people it involved are either saved or damned, then you’ll have misunderstood me.