Australia’s proposed corporate tax cuts aim to attract footloose global capital by offering an internationally competitive tax rate.

Much of the global tax debate, however, focuses on increasing rather than reducing company tax. Specifically, the aim is to discourage companies from shifting profits to tax havens where they pay little or no tax.

New analysis by academic researchers Thomas Tørsløv, Ludvig Wier, and Gabriel Zucman adds compelling data to the case for stronger internationally coordinated action to address this profit shifting.

The broad narrative is familiar, and the tax-avoidance techniques are well known: transfer pricing; intra-company loans; and locating intangible assets (trademarks and intellectual property) in tax havens. From time to time, accidental leaks, such as the Panama Papers, provide detailed insights. But neither the companies nor the tax havens have much interest in providing enough transparency to allow an accurate assessment of the magnitude of profit shifting.

In recent years, however, better data is becoming available thanks to the base erosion and profits shifting (BEPS) project run the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, work by the International Monetary Fund to improve balance of payments data, and work by the statistical office of the European Union. Financial transactions have two sides: when one party provides transparency, it can shed light the other side of the transaction.

This new data provided the basis for the paper’s revealing forensic analysis. In particular, macro-level data on foreign entities provides detail on company income, including in tax havens.

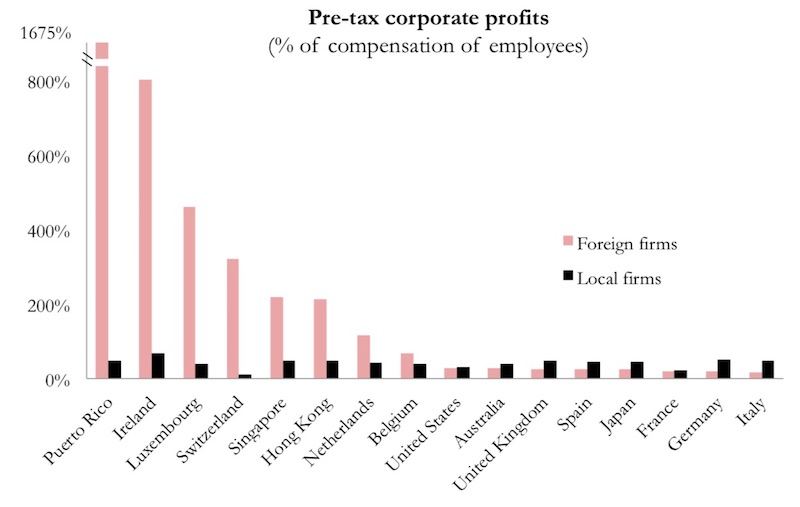

Company output (which makes up more than half of GDP) comprises profits and wages. The ratio of profits to wages can vary with capital intensity and other factors, but when this ratio is abnormally high, it is a strong indicator that profits have been inflated by transfers from associated companies in other countries.

In normal circumstances, profits tend to be around one third of wages. Local companies in Ireland, a notable tax-shifting destination, match this typical ratio. But foreign-owned companies in Ireland record a ratio of around 800% – a sure sign of massive profit shifting into Ireland to benefit from the extremely low tax rate on company profits.

For Ireland, the transfers are around 100 billion euros annually: so large that the national accounts are clearly distorted. In 2015 Ireland recorded a phenomenal GDP increase of more than 25%.

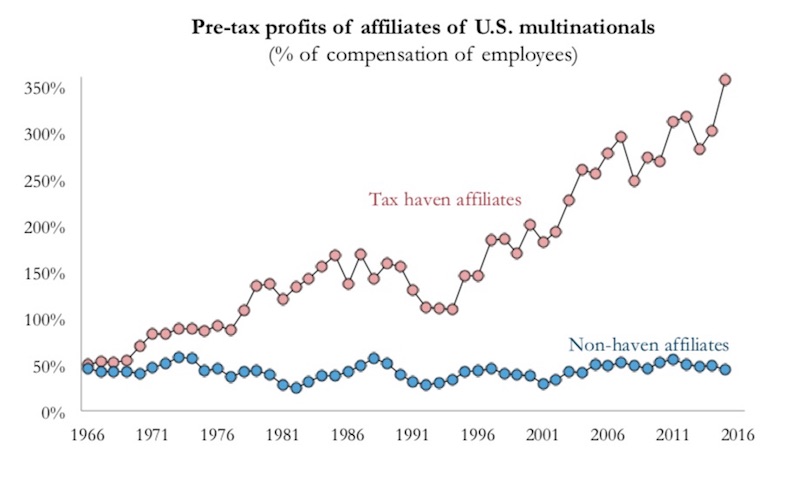

More detailed US data demonstrates the growing prevalence of profit shifting by US companies over the past fifty years.

The authors estimate that at least 40% of multinationals’ profits earned outside their home country are shifted, with the extreme cases being companies with high levels of profit from intangibles and very little conventional capital, such as Google, Facebook, and Apple. The European Union is estimated to lose 20% of its company tax revenue, hence its special interest in requiring Ireland to impose more tax on foreign companies such as Apple.

This analysis suggests that Australia has the wrong priority in corporate tax reform. Of course, Australia participates in the BEPS process, and the Australian Tax Office works hard to address profit shifting (and not only by foreign multinationals, as its current dispute with BHP demonstrates).

But this paper argues that it is profit shifting, not profit competition between countries, that matters.