Nicholas Moore’s Southeast Asia Economic Strategy, a new government-commissioned report on Australia’s economic prospects in the region, is a detailed and comprehensive compendium of trade and investment data, projections, case studies and sensible proposals for responding to country-specific opportunities.

The positive tone of the report reflects the region’s prospects rather than Australia’s current links or past performance. Not only is the region forecast to grow by 4% annually until 2040, but current geopolitics suggests that the best expansion opportunities are within the region. As The Economist has noted: “In 1990, 46% of Asian trade took place within the region. By 2021, that figure had risen to 58%, making it the most integrated continent after Europe.”

The tone of the Report is strongly positive, emphasising what Australia has to offer. But it also notes that Australia’s trade has grown more slowly than regional GDP (5% against 8%), and that two-way investment is tiny.

The gap between perceived potential and actual performance has long been the subject of puzzlement and proposals. With its forward-looking emphasis, the Report says little about this past performance.

But history has lessons. We might use Indonesia – the largest economy and regional leader – to illustrate the disappointing performance. In the second half of the 1960s, as Indonesia pulled itself out of the economic disaster of the Soekarno years, Australia was well placed to play an influential role in Indonesia’s return to normality.

Diplomatic relations had been maintained despite Australia’s armed forces clashing in Kalimantan during Indonesia’s “Konfrontasi” with Malaysia. The aid program was quickly ramped up and Australia played a helpful role in the renegotiation of Soekarno’s foreign debt.

Australia was well-thought-of. Some Indonesians still remembered the role of the Australian wharfies in disrupting Dutch shipping during the struggle for independence, and Tom Critchley’s role in the subsequent negotiations.

Radio Australia was the favoured news source. Australian academics (Herb Feith, Jamie Mackie, Heinz Arndt and his pioneering Indonesia Project at Australian National University) kept Indonesia in the forefront of research and several ANU alumni went on to high office in Jakarta. Indonesian language became a common subject in schools and universities.

Top journalists (Peter Hastings, David Jenkins, Hamish McDonald) gave Indonesia a prominent place in the news. And Australian author (Christopher Koch) and filmmaker (Peter Weir) brought Indonesian history to a world-wide audience with The Year of Living Dangerously, with the central role roughly based on ABC correspondents in Jakarta.*

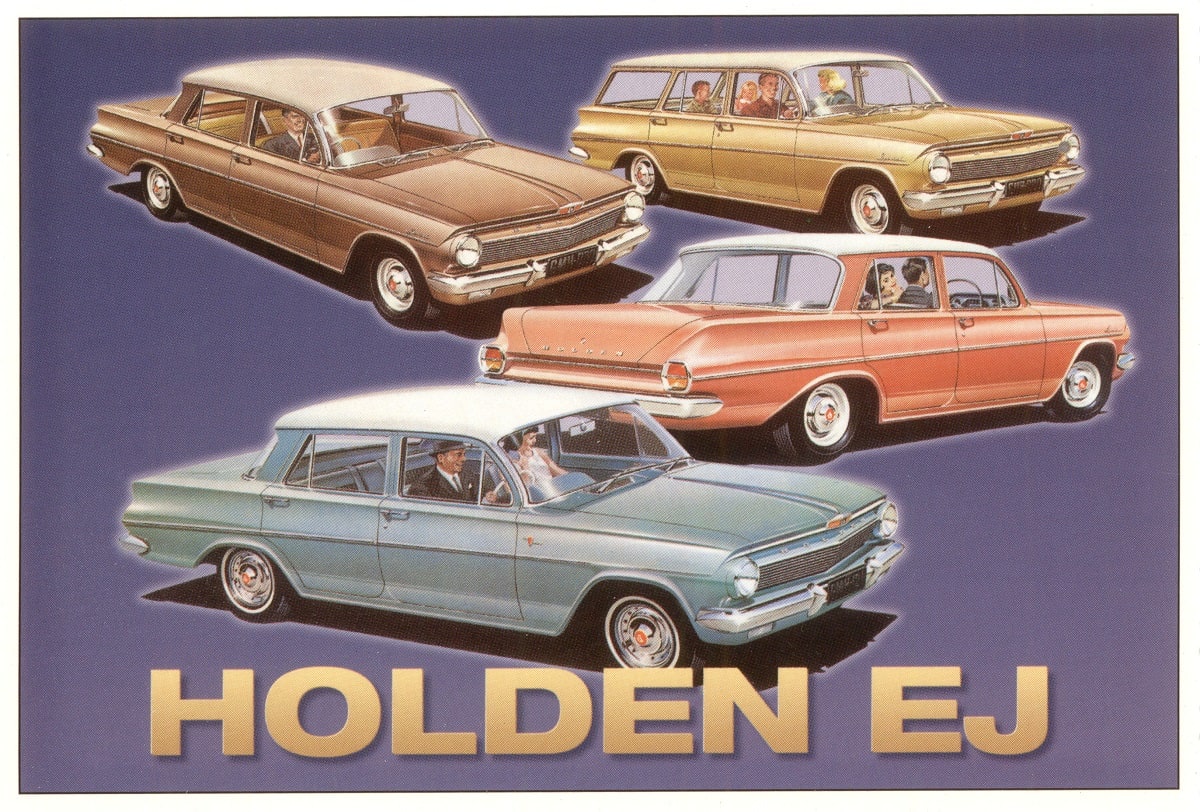

The Australian-made Holden was the favoured family car, with a reputation for sturdy reliability.

Commercial opportunities seemed to beckon: Australian engineers identified the shortcomings of Jakarta’s telephones (“half of Jakarta is waiting to have the telephone installed, and the other half is waiting for a dial-tone”). Australia’s can-do entrepreneurs saw ways to take advantage of our geography: the Kailis Brothers in Perth saw the potential for trade with Java, bypassing Jakarta’s clogged port by rehabilitating Cilacap on Java’s south coast and just a few days steaming from Perth.

Australian companies nationalised by Soekarno (Kiwi and Nicholas Aspro) were among the first restored to their owners.

The business opportunities were widely recognised, with a team of top Australian executives visiting Jakarta in 1967. The big miners were there – BHP and Rio Tinto’s predecessor – interested in Indonesia’s tin and, later on, coal and the enormous Grasberg copper/gold deposit in Irian. Indonesia’s most senior government geologist was in Australia, sussing out the potential for using Australia’s mining laws and regulation as a model for Indonesia.

Australia’s Wheat Board had spotted the huge marketing opportunity of adding noodles and bread to Indonesia’s rice-dominated diet. Instant noodles would drive Indonesia’s wheat imports from 50,000 tons to 4 million today (Australia’s biggest export). The market for “fresh’ milk” (actually reconstituted) was created by the innovative Australian Milk Board.

The ensuing years have seen successes, diplomatic and economic. But this early excitement has faded. The Milk Board’s head-start was submerged by the European milk lake. The big miners, having tried their hand in coal and the Grasberg copper, have now left.

The last residual of the Holden’s coveted status was the Saturday night drag-racing up Jalan Sudirman, now long gone. The Kailis’ Cilacap inspiration withered under Australian bureaucratic caution.

As the Indonesian financial sector deregulated in the 1980s, Australia’s biggest banks sought to establish themselves, but they struggled to learn how to operate in this unfamiliar environment, and either left or scaled back after the 1997 Asian Crisis. None was brave – or tough – enough to try to pick up the gold-mine opportunities as the financial sector was rebuilt from the ashes of the crisis.

Australian newspaper reporting on Indonesia are now sparse, boring and often with a negative slant. Relations have been marred by Timor, and by our spies’ ham-fisted efforts at bugging in Jakarta and Dili.

There is no doubt that Indonesia presents substantial challenges for businesspeople accustomed to the Australian environment. Ways of doing business are unfamiliar and may be hard to reconcile with Australian laws and governance norms. The Reserve Bank of Australia successfully sold its world-leading polymer banknotes to Indonesia but has given up this enterprise after corruption prosecutions in Australia.

As the Report notes: “Some Australian investors continue to view the region's risk–return trade-off as unattractive. … Australian investors undertake significant due diligence … These due-diligence requirements likely explain the lower commercial presence in Southeast Asia due to significant transaction cost considerations.”

But others have overcome the challenges – Singapore, Japan and South Korea, for example. Canada seems to be showing the way, with a four-fold increase in investment: “Canadian institutional investors are a few years ahead of some counterparts in developing trusted relationships for investment, including having spent more time on the ground understanding markets, taking minority stakes in businesses, joining boards, and building experience in the region.”

The Moore Report, sensibly, has a positive and forward-looking emphasis. Its case studies reflect this same positivity. But it might also have been useful to try to identify why the early promise was not realised, and the specific circumstances of success and failure.

* This point was amended following publication as Koch based his character on several correspondents rather than a specific journalist.