Australia experienced two major emergency events in 2020 – the summer bushfires followed shortly after by the coronavirus pandemic. Throughout these events, social media played a critical role in providing information, facilitating social connection and public discussions.

However, there was also a deluge of mis- and disinformation, often spread through coordinated networks. A worrying and persistent element emerged within such networks – extremist messaging by inauthentic accounts that exploited emergency events to magnify their content and recruit followers.

In early January, I tracked a set of 300 fringe, hyper-partisan Twitter accounts that were pushing the #ArsonEmergency hashtag. I was initially alerted to their activity due to automated bot and troll detection tools, which showed a significantly higher proportion of suspicious activity compared to other hashtags. This hashtag, which parodied the popular hashtag #ClimateEmergency, was the centrepiece of a discredited campaign that arson, and not climate change, was the cause of the bushfires.

In this network I observed a worrying amount of problematic content that bumped up against, and in some cases went over, the margins of hate speech, racism and incitement to violence. The example above shows a tweet of an unsubstantiated claim that a “man of Asian descent” was lighting fires – notably, it includes the hashtags #DomesticTerrorism and #ShootToKill. This is an attempt to legitimise the use of violence against particular sub-groups, which fits alongside other baseless claims that other groups such as environmentalists and Muslims were conspiring to light bushfires on purpose.

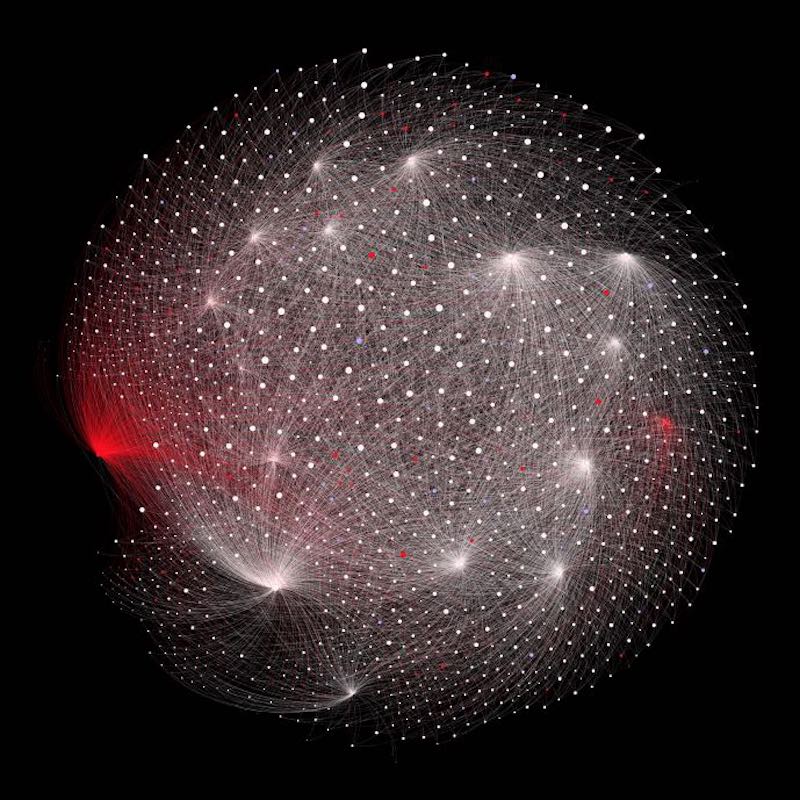

It is no surprise that Twitter has since suspended one in 20 prominent accounts in this #ArsonEmergency network. The figure below shows the follower network for these accounts, filtered to focus on the most prominent nodes (accounts with more than 20 in-links or “follows” from other accounts). Suspended accounts are shown in red (6% of total), deleted accounts are blue (5% of total), and active accounts are white (89%).

Echoes of this #ArsonEmergency and extremist activity were also observed in the United States during the wildfires in Oregon and Washington during September. False rumours circulated on social media that left-wing “antifa” activists were deliberately lighting fires, which led to armed right-wing vigilante groups threatening people in rural communities. The Douglas County Sheriff’s Office in Oregon debunked these rumours and pleaded with citizens to follow official information in order to enable authorities to deal with the fires and minimise loss of life and property damage.

A concerning trend among the #ArsonEmergency account network was the promotion of platforms which are less constrained by content moderation such as Parler and Gab. A number of accounts actively try to recruit people to “free speech” platforms that allow more extremist content, such as far-right and QAnon conspiracy theories (QAnon is now heavily moderated on Twitter). Indeed, QAnon has been labelled as a domestic terror threat in the US, given its advocacy of violence and its anti-Semitic attitudes.

The example below shows the profile of the most active account posting #ArsonEmergency tweets, including a link to Parler and a call-to-action: “Find me on Parler”.

This marketing of alternative platforms aligns with recent concerns that content moderation on major platforms is driving users to self-moderated platforms that are echo chambers of extreme and hateful content. In this way, far-right Twitter networks in Australia are co-opting crisis and emergency events as a staging ground for radicalising individuals into groups such as QAnon. In the process, these accounts weaponise Twitter’s content moderation policies as “evidence” of their conspiracies, using it to drive traffic onto self-moderated platforms where extremist messaging finds safe harbour.

Shortly after the Australian bushfires, the Covid-19 pandemic provided unprecedented opportunities for far-right extremist groups such as QAnon to evolve and spread their messages and networks. In Australia, the pandemic was swiftly politicised and social media activity polarised into a hyper-partisan battleground.

We still have no idea how big and/or active such cross-platform networks are, so mapping these and understanding their dynamics is critical.

The Victorian “second wave” outbreak provides an illustrative case study. Both social and mainstream media were polarised into two camps: those who supported Victorian Premier Dan Andrews’ handling of the outbreak (the #IStandWithDan tweeters) and those who opposed it (#DictatorDan and #DanLiedPeopleDied).

During the various stages of Victorian coronavirus restrictions, social media became a vector to foment anti-lockdown sentiment and protests, culminating in violent clashes with Victorian police. At the same time, Sinophobic memes of Dan Andrews circulated on Twitter and Facebook, keying into racist narratives and hashtags that conflate Chinese identity with the virus. Indeed, the #DanLiedPeopleDied hashtag is a memetic play on the problematic hashtag #ChinaLiedPeopleDied, which features alongside Sinophobic hashtags such as #WuhanFlu and #ChinaVirus.

This online activity was contextualised by an increase in racist attacks and slurs against Asian people both in Australia and globally. Extremist messaging was not solely directed at ethnic minorities. Female journalists also received abuse from a small but vocal core of extremist pro-lockdown activists, including abhorrent threats of physical and sexual violence.

More research is needed to understand how emergency events are co-opted by extremists to push problematic content and build their networks. How successful are these cross-platform recruitment strategies from Twitter to platforms such as Parler and Gab? We still have no idea how big and/or active such cross-platform networks are, so mapping these and understanding their dynamics is critical.

Similarly, how can researchers develop better methods to detect when hyper-partisan organic networks are infiltrated and co-opted by extremists? The distinction is often subtle and requires temporal analysis of large-scale data combined with careful qualitative close reading and digital forensics.

Finally, we need renewed efforts to advocate for better data access for researchers and transparency from social media companies. Public health and safety are directly proportional to the health and accountability of our social media ecosystems.

This article is part of a year-long series examining extremism and technology also available at the Global Network on Extremism and Technology, of which the Lowy Institute is a core partner.