As Donald Trump’s threats against North Korea have accelerated this year, the North has responded with its characteristically over-the-top rhetoric. Recently, it threatened to fire nuclear weapons into the sea around the US territory of Guam, leading to this crisis’ most memorable public takeaway: the government of that island encouraged care in the use of conditioner post-strike, lest radioactive debris cleave to one’s hair.

Last month, the North made another outlandish threat. This time it would test a nuclear device in the north Pacific. South Korean intelligence is hinting at yet another imminent North Korean nuclear test. Could this the first open-air nuclear test in decades? And would this serve as a casus belli for the administration of US President Donald Trump? I have suggested previously that Trump may be trying to bait North Korean leader Kim Jong Un into a provocation outrageous enough to justify the use of force. It certainly feels that way when Trump ad-libs unnecessarily provocative language like ‘fire and fury’ or ‘totally destroy North Korea.’ Trump himself seems decidedly against diplomacy with Pyongyang.

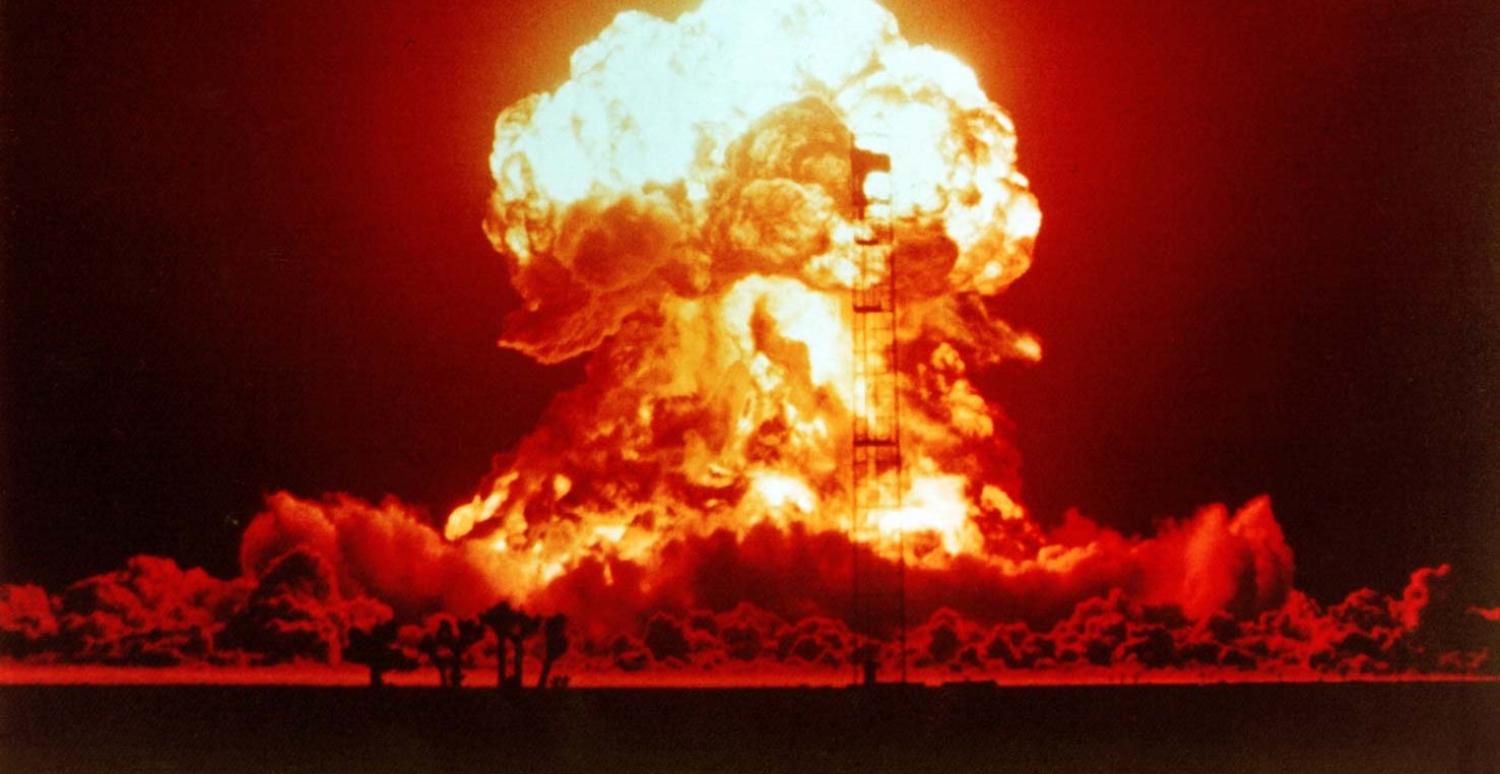

An above-ground nuclear test – or in this case, above water – would indeed be a major provocation. No state has tested a nuclear device in the open air since China in 1980. Although North Korea does not belong to nuclear weapons control regimes like the Non-Proliferation Treaty or the International Atomic Energy Agency, it has nonetheless followed at least the most basic norm of conducting underground tests, if only for its own safety.

But the North’s patience for underground tests may be wearing thin. Its main nuclear test site, Punggyre-ri, suffered a catastrophic tunnel collapse after its last test in September. Its main patron, China, is anxious that radioactivity will leak from Punggyre-ri and drift over the border in a manner reminiscent of the Chernobyl meltdown.

Nor do underground tests seem to be deterring the main target of the North’s program – the US. Trump’s rhetoric has escalated this year as the North's program has accelerated. This is presumably not what the North expected. Its nuclear weapons are to serve a deterrent to US action against Pyongyang, not a stimulant. Perhaps North Korea believes Trump, always so impressed by big, loud demonstrations of force on TV, needs to actually see a mushroom cloud to get the message.

My own sense is that an above-ground test need not constitute a casus belli, but easily could. It would still only be a test. Were the Trump team to latch onto it as justification for an air campaign, global public opinion could still deem a US attack a preventive war of choice.

North Korea, for all its bombast and bluster, has generally been cautious at the strategic level. Its tactical provocations – such as the 1968 effort to kill the South Korean president, or the 2010 sinking of a South Korean corvette – garner attention and are indeed risky. But Pyongyang has never actually escalated to the point of re-opening the overall strategic conflict between the two Koreas, much less the US. This would lead to its destruction. For the same reason, the North ultimately demurred from testing near Guam, and it will likely not do this open-air test either. This threat is probably typical Kimist bluster.

But if the North did conduct an atmospheric test, this could well spark a rolling ‘summer of 1914’-style crisis. In the US, it increasingly appears that the hawk camp is winning the internal White House debate. Trump, Vice President Mike Pence, and UN ambassador Nikki Haley seem to favour action. Secretary of State Tillerson speaks of diplomacy but does not appear to be trying too hard. National Security Advisor HR McMaster also seems to be edging toward accepting conflict. Only Secretary of Defense Mattis seems to still speak resolutely about diplomacy and coordination with allies – South Korea and Japan – who do not want a conflict.

And an above-ground test might change their calculus too, especially Japan. South Korea has long been exposed to devastating Northern retaliation, both conventional and now nuclear. It is unlikely an above-ground test would add much to what is already an existential threat to national security. In Tokyo however, such a test might finally push wavering public opinion in favour of force. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was just re-elected in part on a hawkish position against the North. To test a nuclear weapon in the north Pacific would probably mean a missile launch over Japan (moving the weapon by ship would be slow, easy to stop, and require an exfiltration strategy for the crew). North Korea has launched missiles over Japan before, to the Japanese public’s great consternation. A nuclear-tipped missile, as opposed to an empty test rocket, would be even more alarming. And effects of the explosion – the blast wave, the mini-tsunami kicked up, the radioactive cloud – might well hit Japan itself, depending on where the missile lands. One might even interpret that as an attack on Japan. Even if Abe held his fire in response, he would almost certainly try to shoot down any future North Korean tests near his country.

China too would be put in a terrible position. Its support for North Korea already costs it dearly in global public opinion. An open-air nuke test would be so dramatic, Beijing would likely be forced to respond meaningfully. Its pretensions to East Asian leadership would be thrown into doubt if it stood by while North Korea inflicted a Chernobyl-style event on the region. Its policy space in global public opinion to argue against a US-Japanese (and maybe South Korean) strike would shrink significantly as images of a North Korean mushroom cloud were broadcast around the world.

For all these reasons, I still think such a test is unlikely. Such a test would not formally qualify as a casus belli, but the public relations impact globally, and the possible ecological impact on Japan specifically, could well be enough for the Trump Administration to choose to fight, with Japan in support and South Korea and China ambivalent. The North can see this too and will likely not run the risk – if only Trump can keep his mouth shut during his Asia trip...

Photo by Flickr user International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.