2019 saw a rapid deterioration of Japan–South Korea relations on several fronts. In a culmination of the reoccurring spats over nationalist issues such as reparations for Korean comfort women and protests over the Dokdo/Takeshima islands that have characterised the bilateral relationship in recent years, tensions spread from culture to trade, even seeping into the typically untouched realm of South Korea–Japan security relations.

A major trigger was Japan’s unexpected tightening of hi-tech exports to South Korea, which initiated the so-called Japan-South Korea “trade war”. South Korea’s reaction, however, quickly went beyond economic measures. In addition to taking Japan off the preferential partner list, the South Korean government threatened to suspend the intelligence-sharing pact with Japan and has refused to get involved with the Supreme Court’s decision over Japanese wartime labour reparations.

As analysts have pointed out, South Korean reactions have been shaped by concerns over heightened nationalism and public opinion, particularly since other domestic issues and concerns over North Korea have become a growing source of public discontent. The South Korean Foreign Ministry’s justification of approving the Supreme Court’s decision ordering Mitsubishi to compensate South Korean forced labourers is a prime example, seemingly torn between the emotionality of domestic appeal and the objectivity of diplomacy.

Although alliance politics and security concerns over North Korea did contribute to Seoul reaffirming its intelligence-sharing agreement late last year, trade and cultural issues have continued to fester without much progress.

“We will craft our response in a way that could heal the victims’ pain and wounds, but at the same time, foster a forward-looking relationship with Japan,” ministry spokesman Roh Kyu-deok said in a news briefing.

Following the latest round of diplomatic talks between South Korea and Japan in Seoul last week, it seems that both nations are keen to move towards a reconciliation in 2020. While the talks are a promising first step to improving relations, the apparent inability of either side to stray from an entrenched position makes reaching middle ground difficult. It is telling, for instance, that following these culture-centric discussions, President Moon’s office has issued a reminder that maintaining the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) with Japan remains a “viable option”, but one that is tied to the easing of Japan’s trade restrictions.

Further underlining this complex interplay of culture, security, and trade, Japan launched its second complaint to the World Trade Organisation mere days after the conclusion of the latest round of talks in Seoul.

All in all, a fresh start to Japan–South Korea relations hardly seems likely. Barely two months into 2020, tensions have bubbled over around Japan’s re-opening of a national territory museum in Tokyo. The issue of reparations for Korean victims of Japanese wartime labour has continued to make local headlines, alongside contentions over using the “Rising Sun” flag in the upcoming Olympics and the death of one of the last survivors Japanese sexual slavery during the Second World War.

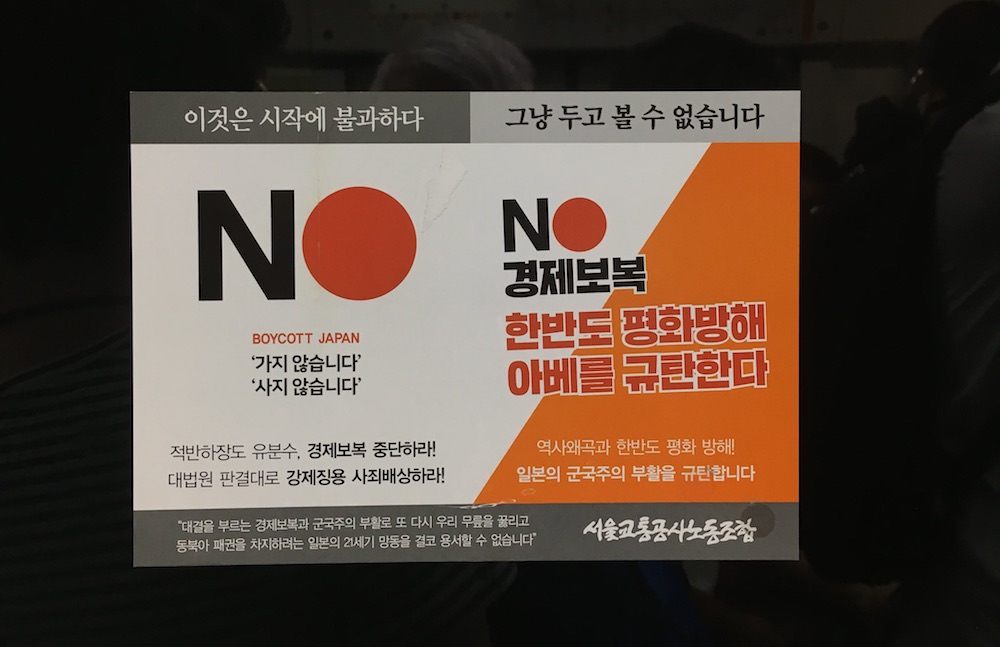

Anti-Japanese sentiments among the South Korean public have been an important contributor to these tensions, with the boycott of Japanese products being felt across a number of industries – for example, imports of Japanese beer dropped to just US$5000 in September, down from $7 million a year earlier. Similar shocks have affected import car sales and domestic and international air carriers.

As South Korea and Japan have reported more coronavirus cases, however, public attention has shifted towards this new crisis. The issue was brought up in the latest round of bilateral talks in Seoul, but apart from agreeing to continue to closely work together to share related information in “a smooth manner”, few tangible outcomes could be observed at this stage.

Given this lack of substantiative progress, there is some potential for multilateral forums to push for a breakthrough. From a China-Japan-Korea trilateral perspective (which got some attention last year with the summit in Chengdu), there is some promise in President Xi’s expected visit to Seoul in the first half of this year. However, this too remains tempered by residual tensions over THAAD deployment and clouded by uncertainty over the coronavirus.

On the alliance front, tensions with the US over South Korea’s defence contribution and preoccupation with US domestic elections have dampened whatever influence the US may exert in pushing the allies to resolve their differences. Although alliance politics and security concerns over North Korea did contribute to Seoul reaffirming its intelligence-sharing agreement late last year, trade and cultural issues have continued to fester without much progress.

Yet, given the interdependence between the two neighbours, even amidst the current crisis an unexpected reconciliation could be imminent. The outcomes of the recent trilateral meeting on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference bear watching, as they shed some light on the prospect of a breakthrough, with the top diplomats of South Korea, the US, and Japan making efforts to address the ongoing tensions, alongside virus outbreak management and security issues in the Middle East.