Earlier this month, 16 Chinese military transport aircraft were sighted a little more than 100 kilometres off the coast of the East Malaysian state of Sarawak. The Royal Malaysian Air Force called it “a serious threat to national sovereignty”. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs summoned China’s ambassador to Malaysia to voice its displeasure over the incursion into Malaysian airspace. However, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson dismissed Malaysian concerns by claiming that the aircraft were there for “routine flight exercises”.

Malaysia is not alone in being wary of Chinese intentions in the region. China’s infamous “nine-dash line” around the South China Sea and unilateral claims to as much as 80% of the disputed waters, along with the construction of artificial islands, has caused much consternation. Regular incursions by Chinese fishing trawlers have occurred in Indonesian, Vietnamese and Filipino waters, and the belligerence displayed by Chinese naval vessels and aircraft has further fuelled suspicions.

Southeast Asian leaders must balance economic realities with defending territorial sovereignty and national pride.

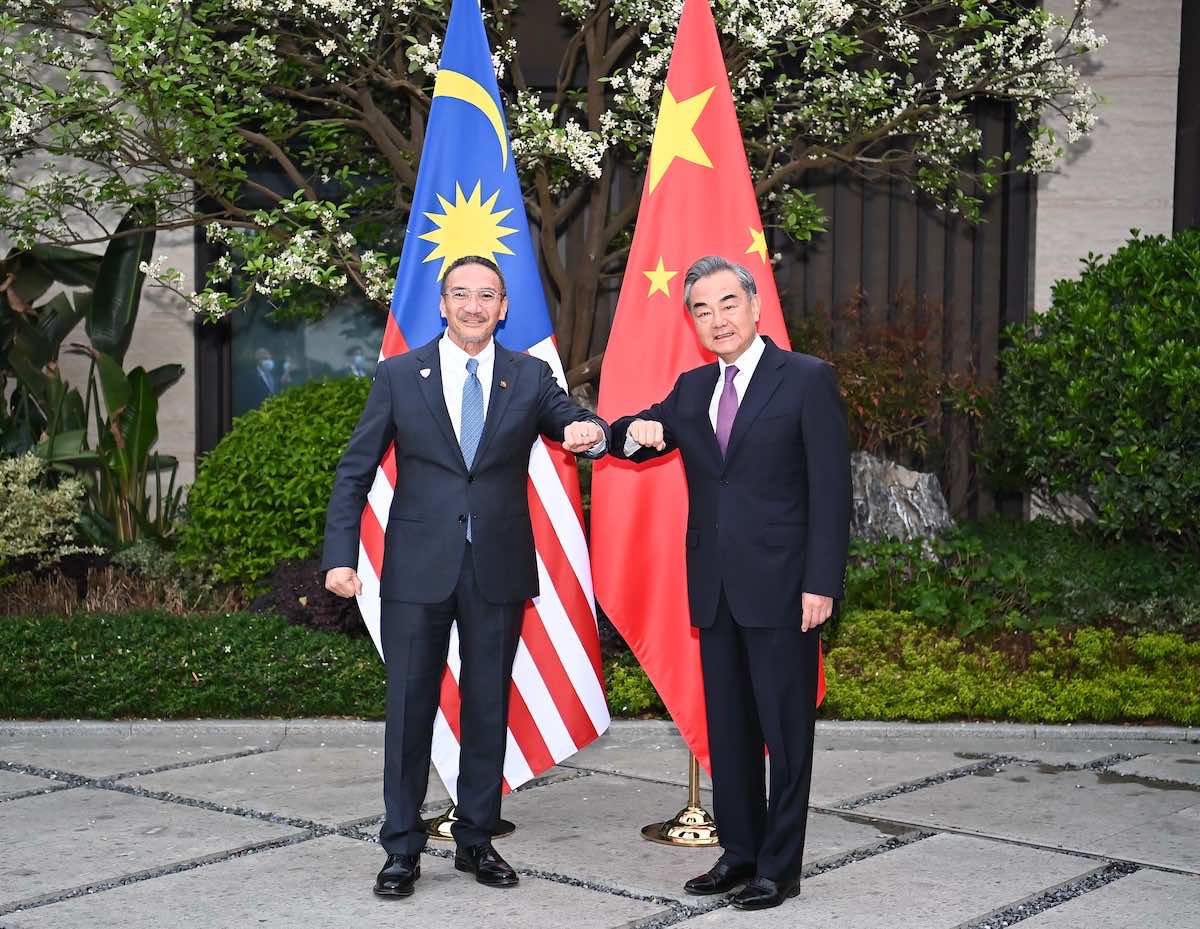

The incursion by Chinese aircraft into Malaysian airspace comes barely two months after a controversial remark by the Malaysian Foreign Affairs Minister Hishammuddin Hussein. During a visit to Fujian province in southern China on 1 April, Hishammuddin told his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi that “you will always be my elder brother”. Prominent Malaysian opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim lamented that “this is not the language and style that should be used in the diplomatic world and international relations, as it seemingly implies Malaysia is a puppet to a foreign power”. Anwar urged Hishammuddin to retract his comment and apologise to Malaysians. Hishammuddin later clarified that his remark was meant to show his respect to Wang, who is an older person and a very senior diplomat.

Hishammudin should have been more cautious with his language. His remarks offer a further warning of the potential cost to Southeast Asian leaders of being seen to defer to China’s sphere of influence. Beijing has calculated that as China gained stature as a superpower Southeast Asian nations would not, and could not, challenge its economic and military might. This was underscored after President Xi Jinping announced in 2015 that China had no intention of militarising the South China Sea, only to then proceeded to build more artificial islands and install missiles and erect buildings and military bases on those islands. The risk for Hishammudin was to again reinforce this lesson.

Southeast Asian countries, including Malaysia, recognise that none of them has the capability to match China’s military might. And the region does indeed have deep ties with China economically, which Beijing is eager to grow. Construction of a high-speed railway service linking Kunming in Yunnan province with Singapore as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) remains a top priority for China. However, Southeast Asian leaders must balance economic realities with defending territorial sovereignty and national pride.

China has been actively cultivating Malaysia through the funding and construction of massive infrastructure projects. In 2016, the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) costing 65.5 billion ringgit (US$15.8 billion) was launched to link Kuantan on the eastern coast with ports in the western coast. The Melaka Gateway, a US$10.5 billion commercial and property development project, was awarded to a Malaysian company that included three Chinese commercial partners. Three pipelines were also awarded to Chinese companies at a cost of US$4.1 billion.

Malaysia was right to be disappointed at China’s action to send military planes close to its borders.

Yet after the ruling Barisan Nasional was voted out of office in 2018, the incoming prime minister Mahathir Mohamed proceeded to review these projects. In a visit to Beijing in August 2018, he warned about the “new version of colonialism” where rich countries preyed on poorer ones in what was taken to be a swipe to China. The three planned pipelines were scrapped a month later. Mahathir renegotiated terms for the ECRL and reduced the cost to 44 billion ringgit in 2019.

With the collapse of the Mahathir government in February 2020, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin proceeded to mend ties with China. In April this year, it was announced that the renegotiated ECRL would cost 50 billion ringgit. However, the Malacca state government cancelled the Melaka Gateway project in November 2020 on the basis that there had been “no development”.

Malaysia’s experience in an example of how China influence is conditioning behaviour in Southeast Asia. In 2019, Nikkei Asia reported that the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations had overtaken the United States as the second-largest trading partner for China. Chinese investments also flow into Southeast Asia, largely through the BRI, the Global Times reporting in November 2020 that China’s investment in Southeast Asia was more than 76% of the total investment in countries and regions linked with the BRI.

But none of this should be cause for Southeast Asian leaders to surrender sovereign interests to a bully in Beijing. Malaysia was right to be disappointed at China’s action to send military planes close to its borders. Malaysia should take a lesson of its own, that China has a “new version of colonialism”. Responding collectively as a region should be the priority.