Joe Biden is about to fly to the United Kingdom on his first foreign visit as US President. Biden will attend the G7 summit in Cornwall from 11–13 June, head to Belgium for summits with NATO and the European Union on 14–15 June, then meet Russian President Vladimir Putin in Switzerland the following day. His trip will be the first time time Air Force One has carried the president abroad since Donald Trump went to London in December 2019, before Covid-19 closed international borders and made diplomacy virtual.

Overseas visits offer unmatched opportunities to strengthen bilateral and multilateral relationships.

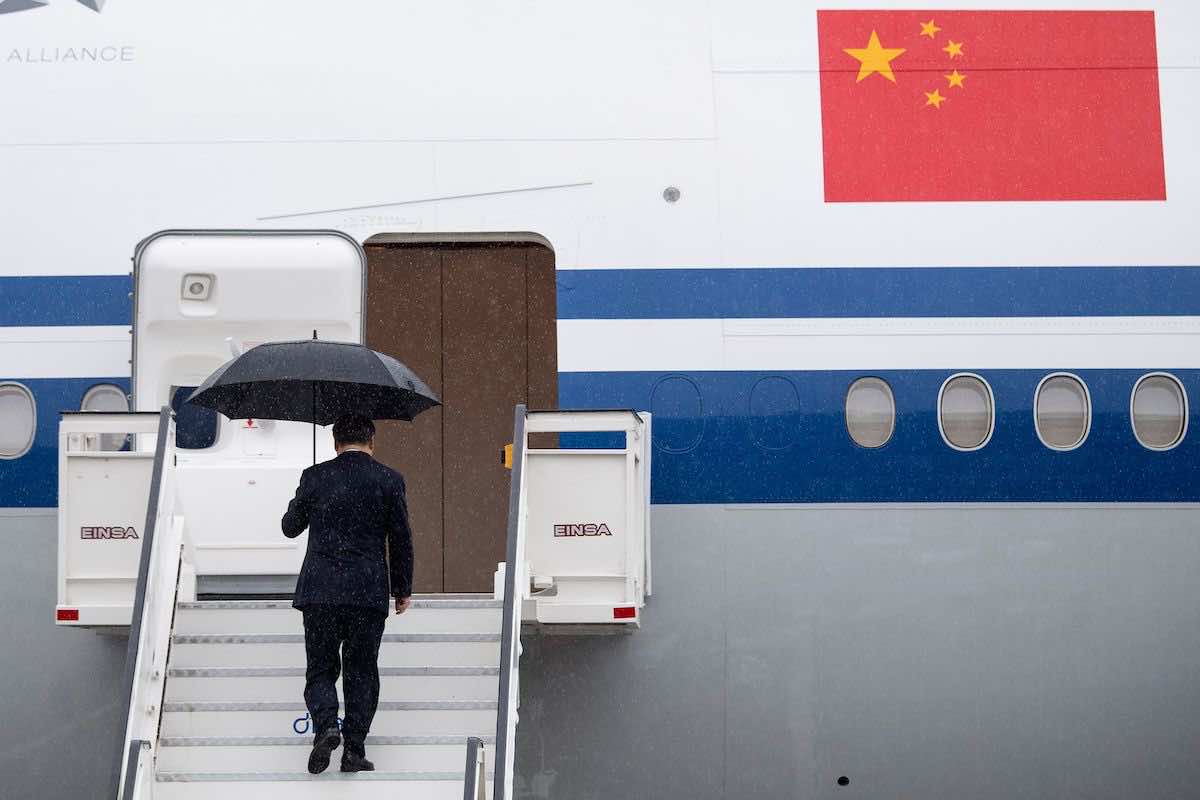

Biden’s first two stops involve talks focused on bolstering diplomacy between democratic countries to counter China’s rising power and the challenges that poses for human rights, economic openness and regional security. Yet despite Biden’s flurry of activity next week, a tally of the past three decades of travel by the presidents of the US and China suggests that Washington is now playing catch-up with Beijing when it comes to presidential diplomacy abroad. China’s President, Xi Jinping, has out-travelled his US counterparts.

Records of US presidential travel can be found in the “Travels Abroad of the President” series maintained by the Office of the Historian in the US Department of State. Chinese presidential travel lacks such an authoritative database but can be tracked through China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and reports in People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s official mouthpiece. These sources allow for a count and comparison of the respective travel itineries.

While there are many other influences on international relations, leadership travel is important because diplomacy is a personalised enterprise, where the old wisdom that “80% of success is just showing up” is widely recognised. Xi’s trips help him lobby world leaders to support Beijing’s policies, to vote with China in multilateral institutions, and to join Chinese programs such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Indeed, scholars have used insights from neuroscience and psychology to show that “face-to-face diplomacy” deepens trust and nurtures cooperation. Leadership visits are associated with more bilateral agreements, investment and aid.

Analysing the data on overseas visits by the US president and China’s president from 1989–2019 reveals that China overtook the United States last decade in the quantity, duration and breadth of its presidential diplomacy. The return of in-person summits after more than a year of travel restrictions provides an opportunity to examine the pre-pandemic record that both countries will build upon.

The US president increasingly ventured abroad after the Cold War and during the period defined by the so-called “war on terror”, but their travel declined markedly as domestic dysfunction intensified following the 2008 global financial crisis. In contrast, trips by China’s president rose steadily after 1989, and in the years since Xi took office in 2013, he has averaged more foreign visits annually (14.3) than his US counterparts Barack Obama (13.9) and Donald Trump (12.3).

Also significant is the time that leaders spend abroad – a week-long stay clearly allows for more diplomacy than a 10-hour stopover. And China’s president is now clocking more hours on the ground in foreign countries, with the average number of days spent abroad rising from 29.6 under Hu Jintao to 34 under Xi. That average has declined for each US president since Bill Clinton, hitting a post-Cold War low of 23 days under Donald Trump.

The charts above include multiple visits to the same country, so it’s worth considering the breadth of countries deemed worthy of presidential diplomacy. China is ahead and gaining on this score, too, as shown in the chart below. In the 2010s, the US president visited 57 countries, while China’s president visited 72. Xi averaged 9.7 countries per year, compared to Obama’s 7.4 countries, and 8 for Trump.

Where are the US and Chinese presidents choosing to travel? Presidential visits reveal a country’s diplomatic priorities and signal which relationships a government believes worthy of attention and resources. This point is especially true for the United States and China, both countries where the president has the final say on major foreign policy decisions.

Asia in the last decade saw the greatest rise in presidential travel for both countries.

Looking at regions, China outnumbered the United States over the last decade in presidential visits to Africa, Asia, the Americas, Eastern Europe, and Oceania, reflecting Beijing’s strategy of building global influence through economic diplomacy with the developing world. The US president only outdid China’s president in trips to the Middle East and Western Europe, locations of key US partners and allies such as Israel and the NATO states. In the 1990s, conversely, the only region that China’s president visited more was Asia.

Asia in the last decade saw the greatest rise in presidential travel for both countries, likely due to its trade centrality, security hotspots, and growing tensions between China and US allies in the region. The US presidential presence has never trailed China’s president by much in Asia this century. China led in visits to Central Asia and South Asia, while the US was ahead in East Asia and Southeast Asia. China’s president also began visiting Western Europe more often, to foster commercial ties that helped China to grow and that helped Beijing to wedge other middle powers against the United States.

Looking at countries, most of the multiple-visit destinations for China’s president in the last decade were neighbors such as Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan, plus regional powers such as Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines – all BRI partners that Beijing wants within its sphere of influence. The US president appeared to prioritise trips to treaty allies and security partners in Europe, East Asia and the Middle East.

The countries with the highest combined number of visits from US and Chinese presidents were France, Germany, Japan, South Korea and India. This implies that both China and the United States view these democratic middle powers as swing states in the emerging “strategic competition” for power in global governance, security and economics.

Countries visited multiple times by the US or Chinese president, 2010–19

| US president | Visits | Chinese president | Visits |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | 8 | Russia | 11 |

| UK | 7 | US | 7 |

| Germany, Japan | 6 | France, Kazakhstan | 5 |

| Afghanistan, South Korea | 5 | India, Spain | 4 |

| Belgium, Poland, Saudi Arabia | 4 | Brazil, Portugal, South Africa, South Korea, Uzbekistan | 3 |

| Canada, China, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Mexico, Philippines, Vietnam | 3 | Argentina, Cambodia, Germany, Greece, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, Philippines, Tajikistan, Vietnam | 2 |

| Argentina, Australia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Senegal, South Africa, Vatican City | 2 |

Biden will meet the leaders of these swing states at the Cornwall G7 summit, which should deliver new commitments on issues related to global norms and the international order. But Xi’s pre-pandemic travel shows how seriously China takes this diplomatic competition.

So if Biden wants to “renew American leadership”, he must sustain higher levels of presidential travel into the future, alongside his packed domestic agenda. That’s because overseas visits offer unmatched opportunities to strengthen bilateral and multilateral relationships. As Biden told Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga in Washington in April, “there’s no substitute for face-to-face discussions”.