Book review: Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder In My Country by Patricia Evangelista (Penguin Random House, 2023)

“When I become president, when I take my oath of office … There will be a metamorphosis,” Rodrigo Duterte announced just weeks before becoming the 16th president of the Republic of the Philippines. “I’m telling you how I would behave … steadily from a caterpillar [and] blossom into a butterfly.”

Realising that the transformative metaphor may not be reassuring enough, Duterte volunteered more details to his incredulous audience, especially the media practitioners that he had threatened and lambasted throughout his fiery presidential campaign: “When I get to be president, I have to tone down on my cursing and all that would be a past, a history. I have to concentrate on what happens to this country and to develop it and make it progress”.

And indeed, during his 2016 inauguration speech, Duterte displayed a remarkable statesman-like spirit, giving credence to his earlier promise of embodying the dignity of the state once in office.

It didn’t take long, however, before it became painfully clear that the new Filipino demagogue was not only going to transform the office of the presidency, but also the fate of a 100-million-strong nation – for the worse.

Just months into office, Duterte began threatening the Philippines’ military alliance with America and even went so far as to swear at both the American ambassador in Manila as well as US President Barack Obama. Later that year, I witnessed his use of obscenities during a formal event at the Malacañang Palace – likely to whip up excitement among his flabbergasted audience – while proudly quipping about how the ghost of his predecessors keep hunting him at night for his shameless lack of statesmanship.

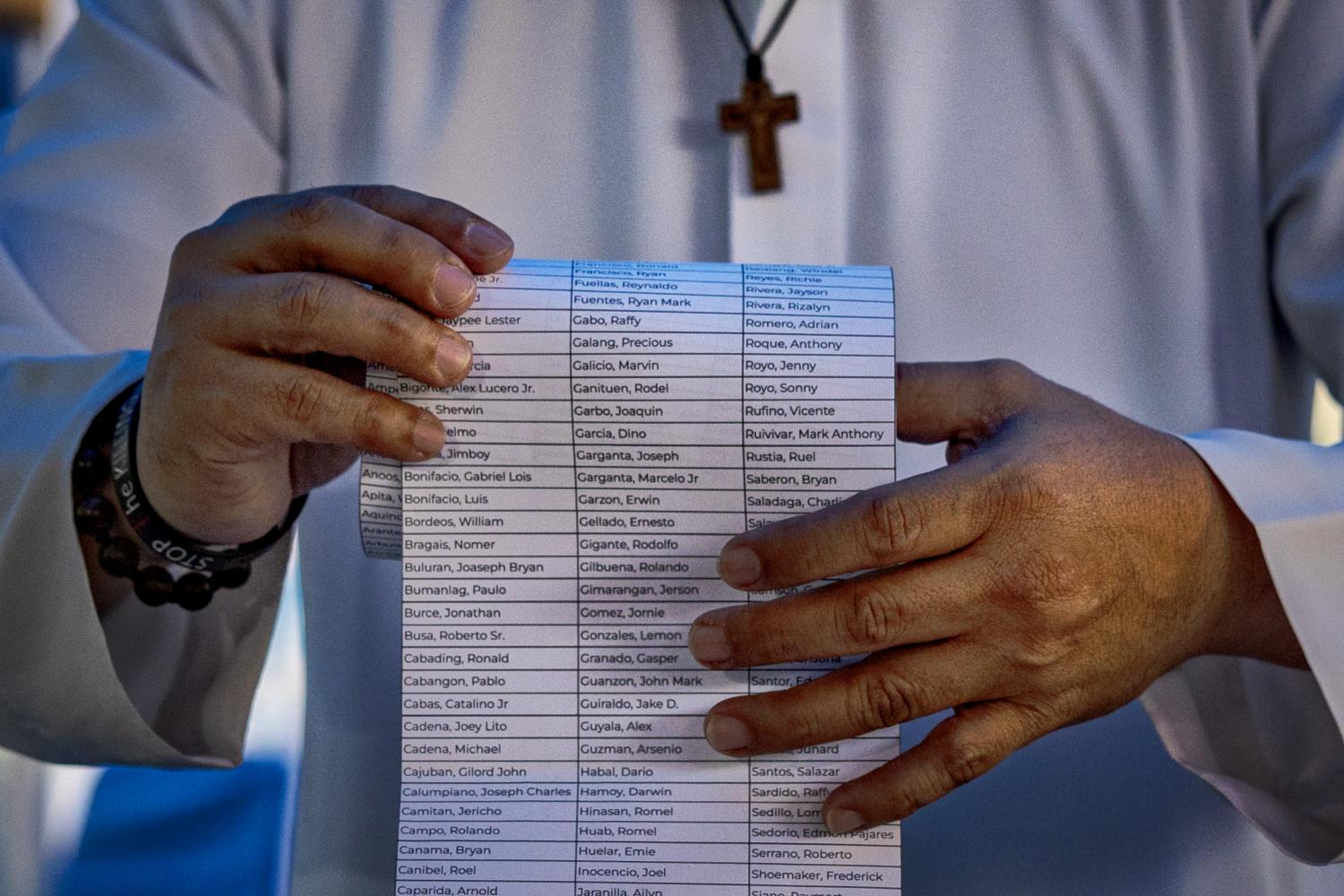

A performer by instinct, Duterte the demagogue just couldn’t help it. Far worse, he couldn’t help unleashing the bloodiest chapter in post-war Philippine history – a so-called “war on drugs” that likely claimed the lives of tens of thousands of Filipinos, including more than a hundred children, almost all the victims from the poorest echelons of the society.

Thus, Duterte became a stark reminder of how it’s best to not only take populists seriously, but also literally, especially when they threaten mass murder.

Enter Patricia Evangelista’s newly-published book, which is among the most compelling works of our era – not only a magisterial work of passionate journalism, but also a wrenching investigation into how Asia’s oldest democracy succumbed to one of the most inhumane policies of the 21st century.

Set in the sprawling slums of Manila, and soulfully chronicling the tragic lives and brutal deaths of young Filipinos murdered under Duterte’s scorched-earth campaign, the book seamlessly weaves reportage, personal memoirs, and social analysis. As a work of journalism, it’s almost unparalleled. As New Yorker’s David Remnick correctly points out, it’s a “journalistic masterpiece”. No journalist, whether Filipino or foreigner, has deployed such peerless combination of descriptive precision, investigative reportage, and gripping prose to expose the unfathomable terror and inanity of Duterte’s drug war, which only empowered the worst elements in the Philippines’ deeply corrupt law enforcement agencies.

As a memoir, the book reflects the author’s literary sophistication and refreshing honesty, including a revealing foray into her family history. Even more, she displays a degree of courage, compassion and vulnerability, which tend to defy her image as a swashbuckling journalist and a vivacious interlocutor.

As a socio-political commentary, however, the book suffers a tendency to place semantics over substance despite occasional reference to prominent scholars. There is no mention of any relevant thinker or theory, which may sufficiently explain why democracies can quickly turn into a fascist dystopia (Think of Michael Mann’s classic The Dark Side of Democracy).

More puzzling, the book reads as if no single book or authoritative study has been written on politics and policies of the Philippines’ most controversial and consequential president. Aside from dozens of high-impact journal articles, which methodically explain the structural preconditions of the rise of Duterte’s deadly populism, several world-class scholars have written full-length manuscripts, most notably Adele Webb’s Chasing Freedom and Vicente Rafael’s The Sovereign Trickster.

To be fair, Evangelista admitted in an interview that in many ways the book remains an unfinished project. Given the depth of the tragedy she personally witnessed and courageously chronicled, and the long-term deep trauma on countless Filipino families and communities, Some People Need Killing is likely just the beginning of a whole new literature on one of the darkest episodes in Philippine history.