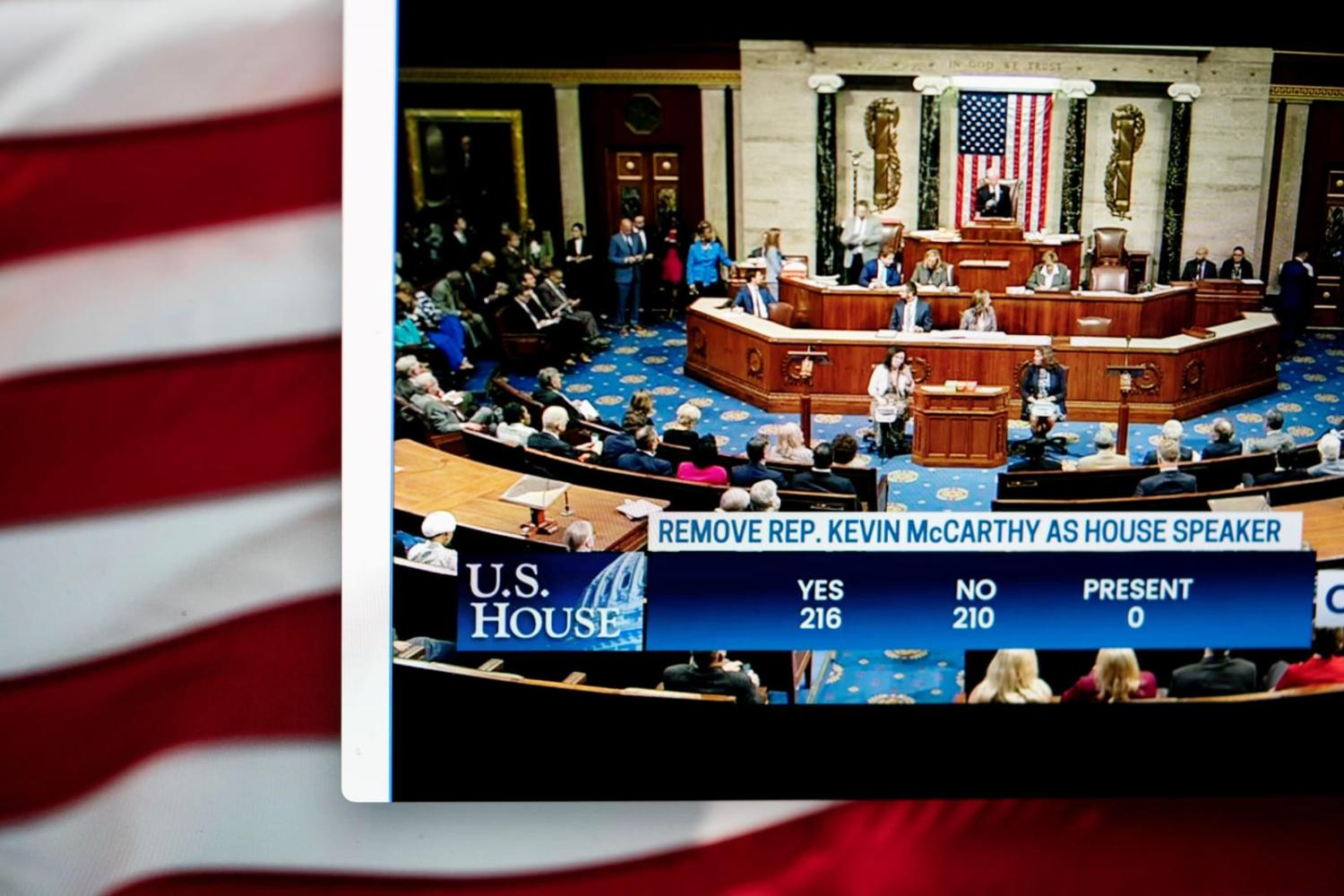

The United States Congress has descended, once again, into chaos. Last week, Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives Kevin McCarthy lost his grip on congressional Republicans, making the momentarily avoided federal government shutdown much more likely as Congress grinds to a halt.

Congressional turmoil and a potentially catastrophic shutdown have significant domestic implications, of course – but the effects reverberate globally.

And this time, one of the triggers for that chaos appears to have come from outside the United States. Far-right Republican Congressman Matt Gaetz, the high-profile initiator of McCarthy’s demise, apparently decided to finally “bring it” to the Speaker because McCarthy had made a “secret deal” with President Joe Biden over American funding for the Ukrainian war effort (though, as always, these claims should be treated with scepticism).

Gaetz and his colleagues in the far-right have long campaigned against American support for Ukraine. Before this latest episode, he and a small group of Republican congress members had refused to agree to more funding, despite Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s personal appeals.

Depending on whom you ask, since the invasion, the United States has provided somewhere between US$76.8 billion and US$113 billion in economic, humanitarian and military support to Ukraine.

In July, Biden asked Congress to authorise another US$24 billion in funding. By the end of September, the Pentagon was warning Congress that it was running out of money for Ukraine.

But Republicans like Gaetz refused to budge. McCarthy only narrowly avoided a shutdown because additional funding for Ukraine was not included in the stopgap appropriations bill agreed to in the few days before the Speaker was dumped. In fact, the deal only passed once US$6 billion in additional aid had been taken out.

McCarthy framed this concession to the far-right Republicans in terms of “accountability” – within the familiar “conservative” focus on budget and debt, a belief that money should be going to Americans first, and a generalised “funding fatigue” with a war that has no end in sight.

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba deflected this as a one-off “incident”, rather than an indication of a bigger problem for the Ukrainian war effort. After all, a large bipartisan majority supports giving more aid.

But this “incident” is emblematic of a much bigger problem – for Ukraine, and for American democracy. Far-right Republican opposition to providing funding to Ukraine, and their increasing willingness to speak about it openly, is symptomatic of a much broader ideological alignment with Vladimir Putin’s Russia long noted by analysts of American domestic extremism.

This shift is a massive change for the party of Ronald Reagan, and one that foreign policy analysts have yet to appreciate, largely because traditional conservatives and American liberals (including Biden) are still split along the historically familiar divisions of the Cold War.

Far-right figurehead Donald Trump’s deep admiration for Putin is unmistakable (remember that weird press conference?) as is his fixation on Ukraine via unfounded conspiracy theories about Biden and his son.

Typical of Trump, though, the circus obscures a deeper reality: Trump likes Putin because the far-right has long had an ideological affiliation with Putin’s Russia. The far-right extremists and white supremacists from which Trump takes his cues see Russia as an idealised white ethno-state that has successfully suppressed minorities, particularly LGBTIQ+ people – all something to be admired, and, hopefully, emulated in the United States.

This ideological affiliation has worked its way into the mainstream. In a 2022 poll, 62 per cent of Republicans and right-leaning independents said that Putin was a “stronger leader” than their own President. As far-right commentator and former Trump adviser Steve Bannon has said, “Putin ain’t woke.” In this far-right framing, Putin is alpha, America is “cuck”.

Last year, NPR’s Odette Yousef, who covers domestic extremism, observed that “Russia and Ukraine have … emerged as a central node in these growing transnational connections between neo-Nazi and neo-fascist groups all over the world.” The situation is fraught and the far-right’s antics corrosive – though not fatal, while national institutions remain resilient.

The ability of a small minority of congressional extremists to torpedo the functioning of the House has significant implications for both American democracy and foreign policy.

There are, of course, immediate consequences for the critical role the United States plays in Ukraine. As the war settles into an apparent stalemate, apathy and congressional gridlock will cause more materiel supply problems. The promised separate bill to increase funding may well not materialise, at least not soon. This has big implications for Ukraine’s ability to continue the fight – as was recently argued in Foreign Policy, debate in Washington “could have existential consequences for Ukraine”. Zelenskyy reportedly told Democratic Majority Leader Senator Chuck Schumer in September that “If we don’t get the aid, we will lose the war”.

The flow-on effects of such a devastating outcome for Ukraine are difficult to understate, particularly in Europe – where the far-right is also on the rise.

All of this points to the inextricable links between the volatile domestic politics of the United States and its global role. As the American far-right toys with the lives of American people, understand that their perverse ruthlessness extends internationally, too.