How does Australia’s economy align with those of our Asian neighbours? What are the development challenges facing nearby South East Asian countries? And just how large is China’s economy? These questions are of particular interest this week as the ASEAN-Australia Special Summit is held in Sydney.

New information now available from a recently published World Bank report helps us make judgements about many economic issues affecting Asia. The report, published under the provocative title “The Changing Wealth of Nations”, provides extensive data on the wealth of countries, to supplement widely used information about annual incomes which underpins conventional gross domestic product (GDP) estimates. This may be the single most notable publication produced by the World Bank in the past 12 months.

There is a crucial difference between the wealth of any country and its income. Annual income (normally GDP) estimates are similar to the income statement of a company and provide a picture of a country’s economic activity in any given year. Wealth estimates, however, are analogous to the balance sheet of a company. They show the value of the total assets a country has built up over many years.

The World Bank observes that “usually, the economic performance of countries is only evaluated based on national income; wealth has typically been ignored”. But the Bank notes that income and wealth are complementary indicators, and economic performance is best evaluated by monitoring both.

The total value of wealth

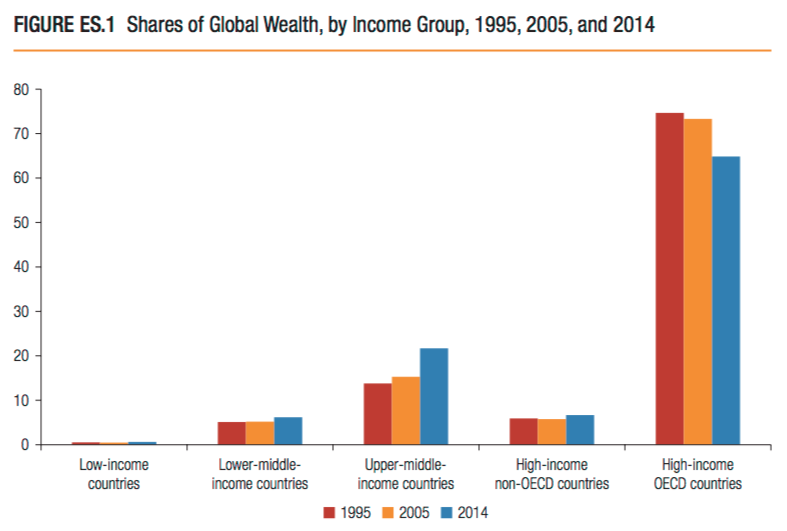

Before we get to a comparison of what these new estimates of wealth show across Asia, first it is important to explore the methodology. Not surprisingly, the estimates show that the differences between the total wealth of countries across the world remains wide. Even though the economic growth of Asian countries (measured by changes in GDP) has been rapid, rich countries still remain very rich, possessing more than 60% of the total world’s wealth.

The absolute gap between high-income OECD countries and other parts of the world remains very large as well. The World Bank estimates that in 2014 the total wealth in OECD countries was more than $700,000* per person, compared with approximately $26,000 in lower-middle-income countries.

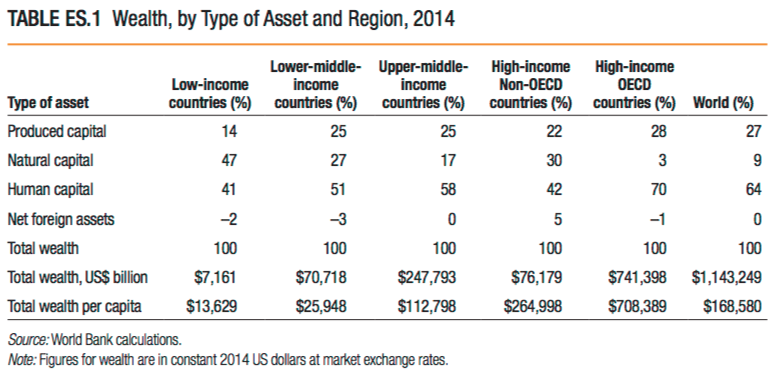

The idea that the average wealth per person in OECD countries is around $700,000 might seem odd. The explanation is that the World Bank’s careful calculations aim to set a value on the total wealth of nations. Four key categories of wealth are included:

- produced capital (things that have been built, such as buildings, roads, and power stations)

- natural capital (both renewable resources and non-renewable assets, such as coal reserves)

- human capital (the current value of learning and knowledge in the population)

- net foreign assets (investments made overseas).

The total value of wealth, and the way that different groups of countries have different combinations of wealth, varies greatly across the world. Low-income countries tend to have a high share of their wealth in natural capital (partly because they have so little “produced capital”). Rich countries, on the other hand, have high levels of wealth in skills and the overall quality of the population.

This way of estimating economic and social wealth goes well beyond calculations of just financial assets. This process of transformation is a crucial part of overall growth and development in many parts of the world, including in Asia.

Wealth comparisons in Asia

The detailed estimates of wealth by country provided in the World Bank report allow many interesting comparisons to be made. Here are only three which cast light on aspects of Australia’s economic relationship with Asia.

First, Australia’s total wealth in 2014 (more than $24 trillion) was roughly double Indonesia’s wealth (around $12 trillion). But it was considerably smaller than the total for ASEAN as a whole (more than $36 trillion).

In other words, in terms of wealth, the ASEAN economy is already around 50% larger than the Australian economy and, relying on GDP figures, is growing at around 5% each year.

Second, the need for investment in physical capital, such as infrastructure, across ASEAN is urgent. Many Australians believe that infrastructure in such sectors as road and rail has been neglected in recent years. However, by international standards, Australia is very well-supplied with physical assets. The World Bank put physical wealth in Australia in 2014 at around $310,000 per person – roughly 20 times the level in Indonesia, which is approximately $15,000.

Because of the shortages of basic facilities, such as water and electricity, across Asia that these figures reflect, the Asian Development Bank has estimated that developing countries in Asia need to invest around $1.7 trillion in infrastructure each year throughout the next decade to 2030.

One key implication of the investment gap between Australia and nearby Asian countries is that there are, in principle, many unexplored opportunities for closer economic cooperation. China is providing support through its new Belt and Road Initiative, but the Chinese programs only scratch the surface. For many years, Australian economic diplomacy in Asia has focused largely on trade rather than investment. Looking ahead, there needs to be much more emphasis on Australian links with ASEAN in the finance, investment, and infrastructure sectors. To focus mainly on trade is not enough.

Third, despite rapid growth in investment in China in recent decades, the nation itself is still quite short of physical capital and needs to continue promoting development at home. The stock of physical wealth in China in 2014 was around $30,000 per person – much lower than that in OECD countries.

Indeed, these latest World Bank figures indicate that for decades to come, China’s leaders will need to focus mainly on domestic rather than international challenges. China’s total wealth in 2014 was only slightly more than $100,000 per person – around one-tenth the level in rich countries, such as the US and Australia. In economic terms, America can be expected to continue to overshadow China for decades to come.

During his second term, President Xi Jinping is likely to spend much more time worrying about the need to strengthen the Chinese economy at home than planning how to expand Chinese economic influence overseas.

* All figures in US dollars.