Of the several spectres haunting Europe, the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline is one of the most persistent. This week, the project hit another snag. Its approval process was temporarily halted by the German energy regulator because Nord Stream AG, the Swiss-based consortium which owns the pipeline (itself majority-owned by Gazprom), had not established a German subsidiary as it is required to.

Predictably, this decision sent further shockwaves through European gas markets, with spot prices jumping to almost 90€ per megawatt-hour. Despite the pain this will cause consumers and leaders, and the apparent strength of Russia’s negotiating position, it also creates an opportunity to accelerate the much-needed diversification of Europe’s energy away from gas.

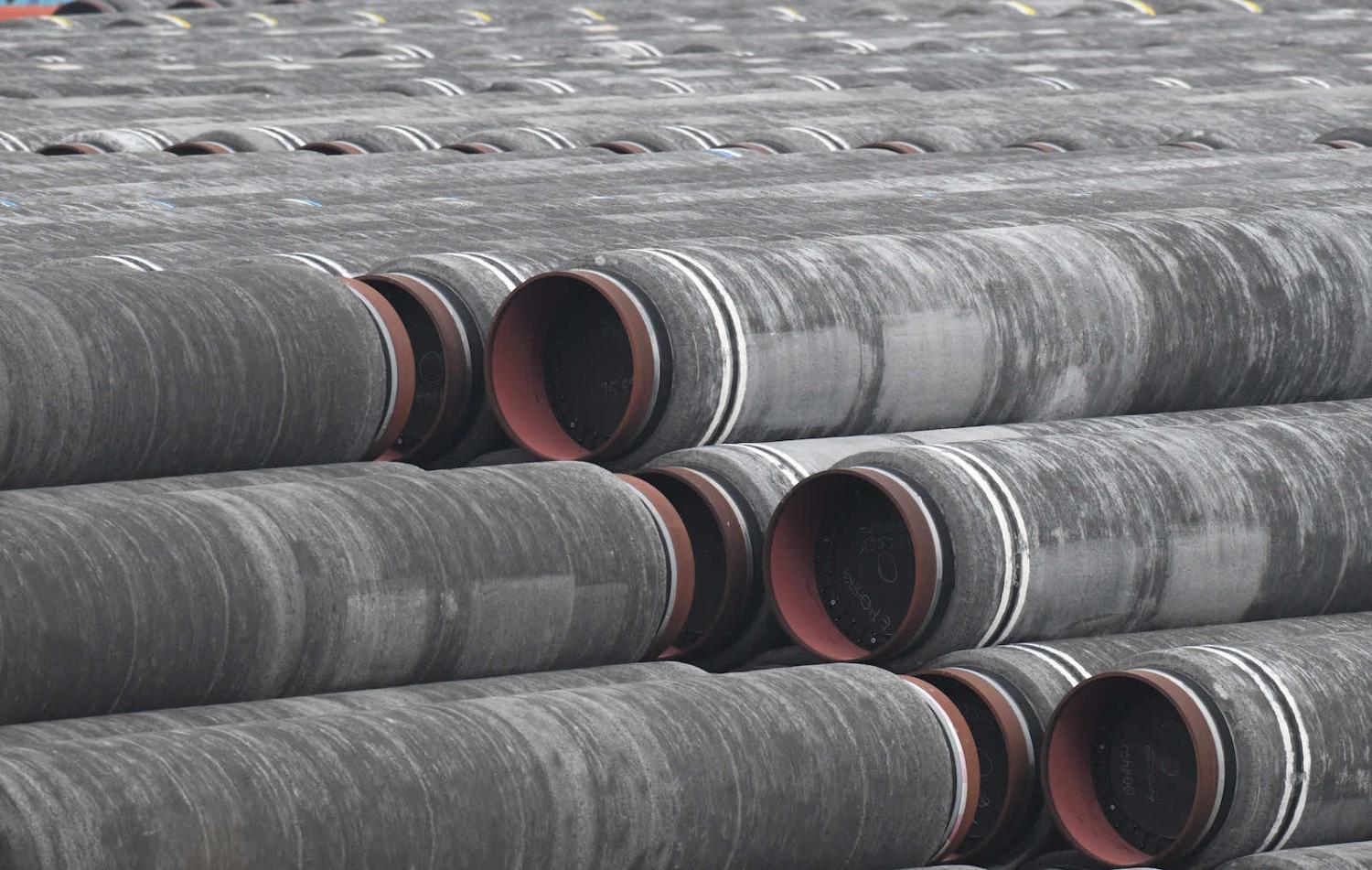

Completed but not yet certified, Nord Stream 2 stretches for 1,230 kilometres from Russia’s west coast to Germany’s north-east. When it commences operations, most likely after the European winter, it is expected to contribute 55 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas to the continent (the European Union currently imports approximately 400 bcm each year).

Russia may be behaving wrongly but it is also behaving rationally.

The project’s critics point to two major security risks: that Nord Stream 2 will deepen European reliance on Russian gas and that its operation will isolate an already vulnerable Ukraine from the lucrative inland network (Poland and Slovakia have also expressed strong criticism of the project for similar reasons).

Yuriy Vitrenko, CEO of Naftogaz, Ukraine’s largest oil and gas producer, estimates that Nord Stream 2 coming online would cost Ukraine roughly 1.5 per cent of its GDP each year in lost export earnings and the stranding of existing transmission assets.

An economic problem is also a political one: in characteristic style, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said on Monday that “a choice is shortly coming” for Europe, between consuming more Russian fossil fuels or “sticking up for Ukraine and championing the cause of peace and stability”.

Russia may be behaving wrongly but it is also behaving rationally. Natural gas is more than just a major export earner – it is also a potent strategic weapon.

Partly because of its declining domestic production, the European Union presently relies on Russia for more than 40 per cent of its natural gas. Through Gazprom, which is majority-owned by the state, Russia is therefore able to create a conundrum for European leaders: attempt to halt certification of Nord Stream 2 in the short-term, which would further drive up already surging energy prices, or effectively concede that Ukraine will be bypassed.

It is an urgent problem: European gas prices have increased by more than 600 per cent this year on the back of low inventories, increased demand following the lifting of Covid-19 lockdowns, and Gazprom not increasing supplies beyond what it is contracted to deliver.

European leaders are in a bind. But their conundrum also brings opportunity.

It is tempting to believe that quick certification of Nord Stream 2 might ease the pain. But that’s only half the story. As Columbia University’s Adam Tooze explains, for 15 years, the European Union has made a “substantial physical and financial investment in integrating its system of gas supply with global energy markets”, with the aim of creating a global gas market and thereby reducing its dependence on Russian supplies. This has entailed major investments in gas infrastructure but it has also changed how the European Union purchases its gas: it has progressively moved away from Russia’s preferred model of long-term contracts toward transacting through the spot market. This enabled billions of Euros in savings when gas prices were low (which had the added benefit of moving Europe away from coal, reducing its carbon emissions) but today, as the European Union competes with Asia on the open market, it has been exposed to price risk. Flexibility has been purchased at the cost of price certainty.

There is, therefore, a good case to be made that years of investment in liberalising its gas market has inadvertently made Europe more exposed to the global price shocks of past months – creating a knock-on effect of now once again seeking relief from Russia.

European leaders are in a bind. But their conundrum also brings opportunity.

Last week, COP26 ended with a renewed commitment from world leaders to phase down coal production and attempt to meet Paris Agreement targets. Meanwhile, fossil fuel prices show few signs of stabilising.

Europe’s response should be to accelerate its investment in renewables. The European Union is clearly committed to gas forming part of its future energy mix. But, given the strategic risks, it must get creative – and quickly. Wind and solar should be at the forefront, but the situation is too urgent to ignore more speculative and, perhaps, controversial energy sources.

Following the Fukushima disaster, German chancellor Angela Merkel pledged to wind down her country’s nuclear industry. That now appears to have been a mistake. But it is not too late. Negotiations are still ongoing to form the first government of the post-Merkel era. Despite the Greens being one of the coalition partners, reviving Germany’s nuclear industry should be part of the conversation. And the European Commission has not yet made a final decision about whether nuclear power should be included in its sustainable finance taxonomy goals.

Diversifying away from risky fossil fuels won’t bring relief overnight. It will also create new risks. But, by reducing its reliance on the caprices of a geopolitical adversary and volatile global markets, Europe can make progress on its environmental and its security objectives.