The weekend announcement of a freeze on North Korean nuclear and missile tests appears stunning. The political implications are profound, yet the decision is also influenced by practical developments. Technical factors relating to both missile and nuclear devices suggest that North Korea has not sacrificed as much as many suspect.

North Korea’s nuclear test site at Punggye-Ri has hosted six nuclear tests since 2006. The latest test in 2017 was of a thermonuclear device. Although it is difficult for outsiders to get a detailed assessment of conditions at the site, there are strong reasons to believe that Punggye-Ri is unusable for future nuclear tests.

The local geology has possibly been altered by this sequence of underground explosions, making the area unstable. The ability to stage further tests and keep the radioactive material sealed is now compromised. North Korea has no other established testing zones in its own territory, and finding a suitable site for a future one would be difficult. North Korea’s geography limits these options.

If the nuclear testing ban holds, one major fear for the near-term will be defused. North Korea had earlier floated the idea of an atmospheric nuclear test over the Pacific Ocean, probably using a missile-delivered warhead.

Last year, I wrote on The Interpreter that a Pacific test would be one way to get around the aforementioned limitations of North Korea’s underground test site. But the environmental and security implications of such a test would be catastrophic.

Nearby aircraft could experience electronic failures resulting from the Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) effects of the nuclear detonation, potentially causing hundreds of casualties. Satellites could also be damaged. Local waters would be contaminated by fallout, affecting fishing as well as shipping. The political and strategic repercussions would be grave.

This means avoiding a Pacific test is probably the most significant short-term benefit of this freeze.

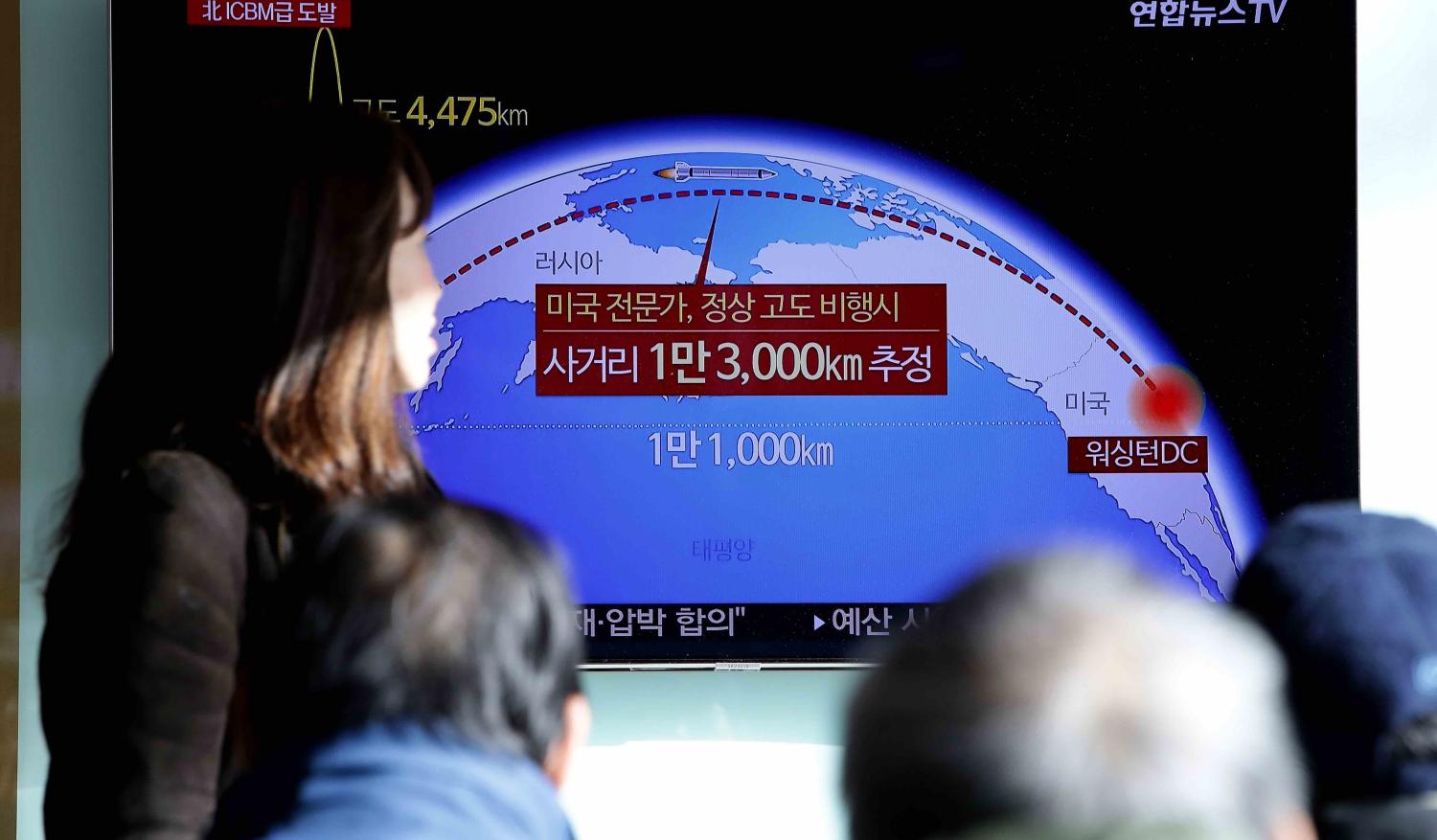

North Korea engaged in a frantic series of missile tests across 2017, stunning boffins with the frequency and variety of launches. In retrospect, it seems probable that North Korean officials were adhering to a deadline to develop an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capability before the end of that year.

Having proven this capability with long-range flights, there is less to be gained by further testing. North Korea has not carried-out a single missile test in 2018, possibly for political reasons, but also to allow time for the previous testing frenzy to be examined.

We cannot, however, totally rule out the possibility of more missile tests, albeit in a thinly cloaked disguise. In December, the South Korean newspaper JoongAng Ilbo reported that local intelligence sources were expecting a North Korean satellite launch soon. The launch would take place from a mobile transporter-erector-launcher vehicle, similar to the ones used to support North Korean ICBM tests.

Essentially, such a process would closely mimic the test of a ballistic missile, and would use a modified ICBM as the launch vehicle. Yes, there really would be a satellite placed in orbit, assuming that the launch worked. But the classification of the launch as a civilian satellite flight instead of a missile test would exploit what appears as a loophole in the freeze statement.

Previous North Korean satellite launches have used cumbersome and fragile rockets that flew from North Korea’s two spaceports, located on North Korea’s west and east coasts. The rockets were unsuitable for use as military missiles. Despite the fact that these launches helped North Korea to develop missile technology, there was a distinction between the satellite launches and missile tests.

The development of powerful military-grade missiles that could potentially fulfil either role has now blurred that distinction. Satellite launches could soon become a smokescreen for North Korea’s missile tests.