The presidency of South Korea’s Moon Jae-in will be bookended by Winter Olympics – one defined by hope, the other despair. North Korea has confirmed it will not participate in the Beijing Winter Olympics because of the coronavirus and what it calls the “hostile policies” of the United States. The decision kills any hopes left that Moon could revive a dialogue with the North in Beijing after he refused to join a US-led diplomatic boycott of the games – and marks a stunning contrast with the fortunes experienced in 2018 when South Korea hosted the winter games in PyeongChang, which became a platform for Moon to launch his détente with the North.

It is remarkable how far Moon has gone but how little he has achieved in the span of four years. For sure, it was not all Moon’s fault. He did all he could under severe constraints posed by the enduring US-North Korea mistrust, growing US-China tensions, and a once-in-a-century pandemic. However, like his two pro-engagement predecessors Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun, Moon cannot change the 70-year-old peninsula status quo with his proactive and engaging North Korea policies.

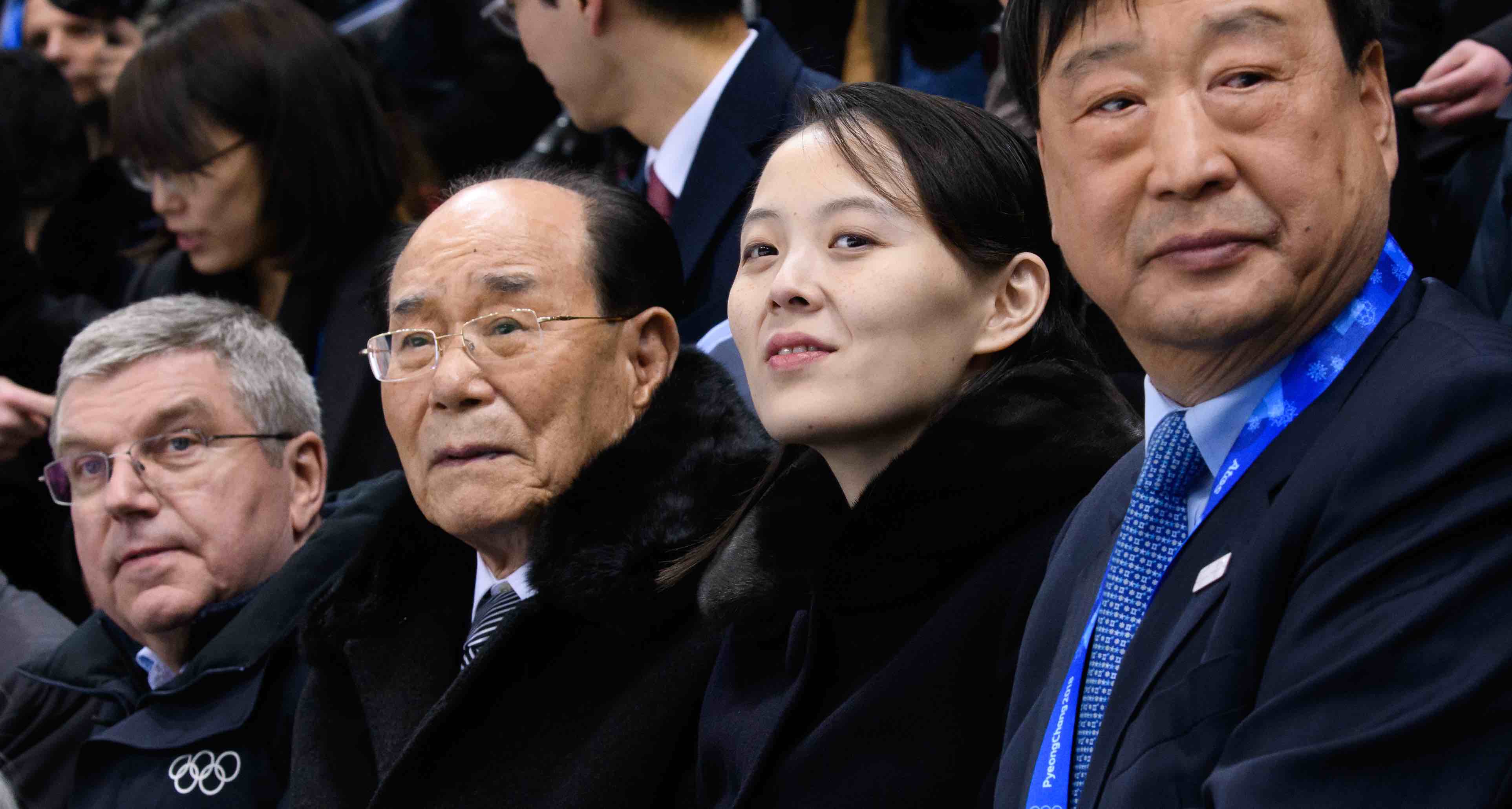

The PyeongChang Olympics was an occasion of peace and hope for the future of the Korean peninsula after a year of “fire and fury.” It also marked the beginning of many firsts in inter-Korean affairs. For the first time, Kim Yo-jong, a member of North Korea’s ruling family, set foot on the South and sat close to the then US Vice President Mike Pence at the Olympics opening ceremony. She formally invited Moon to visit North Korea, and just a little more than two months later in April, Moon and North Korea’s chairman Kim Jong-un had their first summit in Panmunjom and Kim became the first supreme leader to visit the Southern side of the military demarcation line. They would later meet another three times (May 2018, September 2018, June 2019), a record set by the leaders of the two Koreas. The inter-Korean exchanges helped broker the three unprecedented US-North Korea summits in Singapore, Hanoi, and the Korean Demilitarised Zone.

In a stark contrast to the cooperative PyeongChang Olympics, the Beijing Winter Olympics has so far been seen as a divisive occasion.

Unfortunately, the number of summits and declarations does not translate into real progress on denuclearisation and peace building. As the spectacle surrounding the summits faded, Moon soon found himself in trouble as he could not make the United States and North Korea solve their own sequencing problem – whether sanctions relief or denuclearisation should come first.

The collapse of the 2019 Hanoi summit and the onset of the pandemic in 2020 posed an insurmountable challenge to Moon’s détente. He continued to offer initiatives to kickstart talks, including an end-of-war declaration, a barter exchange to bypass international sanctions, and a prospect of another inter-Korean summit (even virtually). However, most of his initiatives proved fruitless as it became apparent that North Korea had lost its appetite to talk, shutting down its border to fend off the virus.

Moon’s failure to achieve concrete results has the same deep cause as his predecessors Kim and Roh’s futile engagement policies. The mistrust between the two Koreas, the United States, and China is immense, regardless of whether or not there is a pandemic. North Korea regularly criticises the United States and South Korea’s “double standard” for condemning its missile tests as aggressive while the two allies are free to build up their arms for defensive purposes. The United States sees the end-of-war declaration as undermining its military presence in the South in the context of US-China tensions and rewarding North Korea for its bad behaviour without any concrete promises that Pyongyang will uphold its end of the deal. China supports inter-Korean engagement and the declaration not because it wants peace but because it wants South Korea to chart a more independent foreign policy from the United States. Even between the allies, South Korea is suspicious of the US attempts to impede its inter-Korean engagement and does not want to be trapped by US conflicts with China.

These problems among the four parties are not new; instead, they reflect the status quo that has long shaped the choices of regional leaders. Moon could make history, but he could not escape these the structural constraints.

In a stark contrast to the cooperative PyeongChang Olympics, the Beijing Winter Olympics has so far been seen as a divisive occasion. The United States has launched a diplomatic boycott and put pressure on its allies to join the bid. North Korea in return condemned the US boycott as preventing China from successfully hosting the event, a signal to its general dismay at US “hostile policies”. South Korea wanted to break with the US boycott to revive the PyeongChang spirit in Beijing but has now accepted that an inter-Korean summit would be impossible due to North Korea’s lack of interest in dialogue.

The diplomatic boycott begs an important question. If the peaceful PyeongChang Olympics and the subsequent diplomatic initiatives could not lead to a major positive change in inter-Korean relations, will the divisive Beijing Olympics be able to? With the South Korean presidential election two months away and the Biden administration relegating North Korea to a low priority, Moon’s successor will have a lot to tackle. Continuing Moon’s engagement policy may not bring concrete results but abandoning it will certainly open the door to potential “fire and fury” in the future.