On 18 April, The Australian newspaper reported that Chinese students had “defied” warnings from their government about safety in Australia and enrolled in record numbers in the country’s universities for 2018.

It was a nice image, of brave families and their children standing up to an authoritarian government so they could study in democratic bliss down under. With an air of dread hanging over bilateral ties, the article qualified as a rare good news story.

Australian politicians and business leaders have been on edge for months about possible economic retaliation from Beijing over allegations of the Chinese party-state’s meddling in local politics.

Business chiefs, led by mining magnate Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest, held a full press court at the annual Boao Forum in Hainan in early April, warning of the dangers to business from deteriorating ties. Many of the journalists amplifying their concerns had been flown to China’s Davos-style conference by the companies themselves.

The business leaders are worried for good reason. Beijing has publicly punished a range of countries in recent years, most notably South Korea (over the deployment of a missile defence system), Norway (awarding the Nobel Prize to a Chinese dissident), and the Philippines (relating to the South China Sea).

Any good cheer they might have derived from the robust student figures lasted only a day, swept aside by an interview in The Australian with Beijing’s Ambassador to Canberra, Cheng Jingye, published on 19 April.

The two countries’ ties, Cheng said, had been harmed by “systematic, irresponsible, and negative remarks”. If the situation didn’t improve, then trade relations could be damaged.

The Ambassador’s remarks were a reminder of two things: that Australia is a long way from repairing relations with China; and that when Beijing wants to punish another country, it does so publicly in order to drive their message home not only to the target government, but also to its citizens.

Still, Cheng’s interview reinforced the impression from my own conversations with Chinese officials and scholars that Beijing is not yet ready to pull the trigger on sanctions against Australia, for a number of reasons.

For starters, Beijing has a bigger adversary to handle at the moment, in Donald Trump. When it is seeking to portray itself as the reasonable party in a nasty dispute with its superpower rival, Beijing doubtless does not want a big fight on another front with Australia.

Australia is not only an important trading partner of China’s. It also abhors Trump’s unilateralism on tariffs and the like. In the 1990s, Australia invariably backed Japan in its trade battles with the US.

On top of that, the big bazookas in Beijing’s arsenal – interfering with tourism, education, and resources – all rebound on China in difficult ways.

The choice that Chinese families make to send their children to study in Australia and holiday down under are the fruits of their country’s success. Would Beijing really want to take those freedoms away from its citizens with crude sanctions?

China often says Australia should be more grateful for the income it earns from the massive resources trade, primarily in iron ore and coal. But the truth is that we are selling them what they want.

The trade is mutually beneficial. Chinese steel makers, powerful political players in their own right, would not be pleased to have to hunt for more expensive resources elsewhere in the world.

Beijing may think that, whatever happens, the best course of action is to wait for regime change, calculating that a Labor victory in the election due next year will bring a friendlier government to power in Canberra.

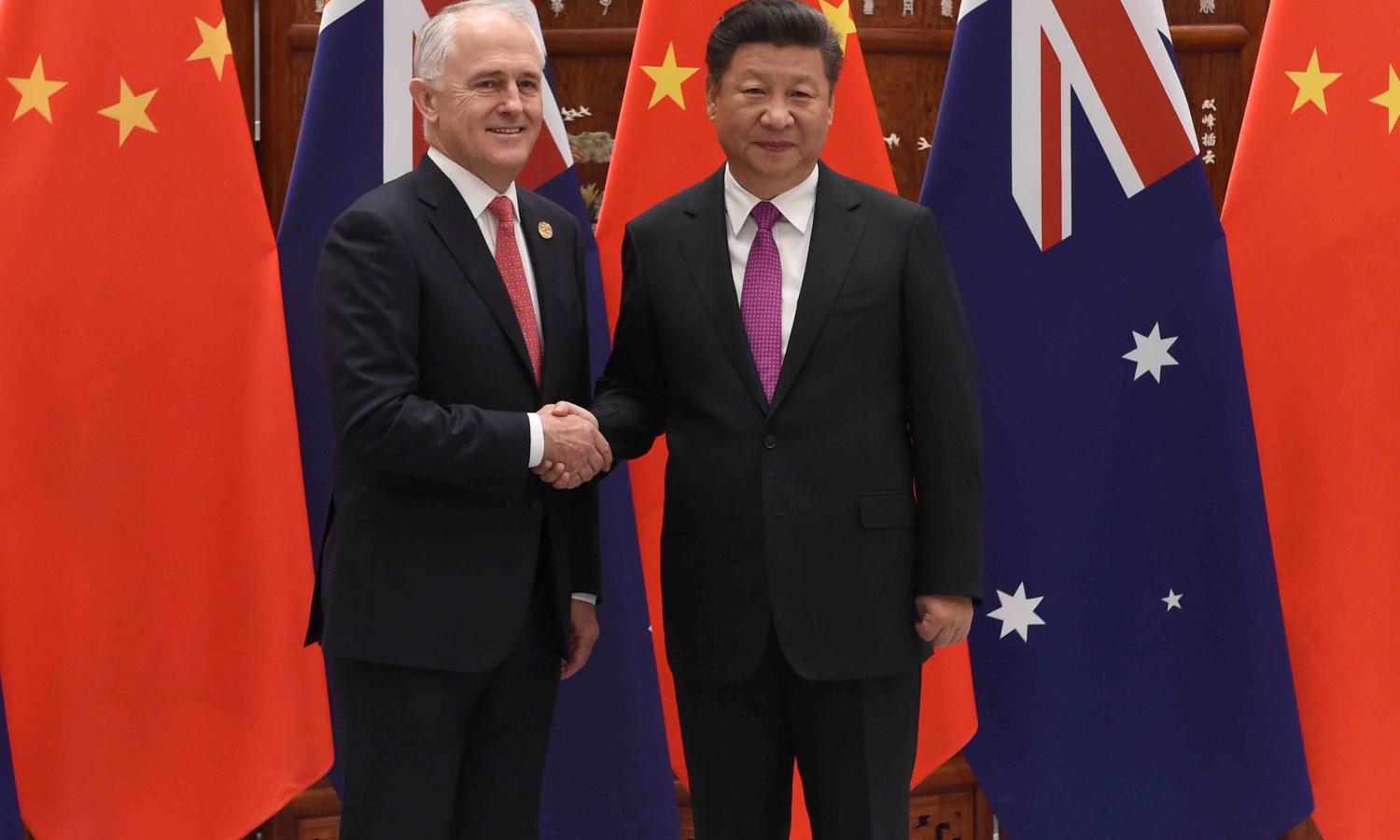

Still, a genuine bilateral reset will be difficult. Whatever rhetorical missteps Malcolm Turnbull has made – most notably, his eccentric and ill-advised regurgitation of a statement attributed to Mao Zedong, which inevitably infuriated Beijing – the outlawing of foreign interference as a principle has bipartisan support.

Once legislation passes (something admittedly not guaranteed before the next election), prosecutions may follow. How will China react to the spectacle of Australian courts exposing and delivering judgements on the opaque and covert relationships between Beijing and pro-Chinese Communist Party front groups in Australia?

The answer is not well. Australia’s push back against the CCP interference has been bad enough in Beijing’s eyes. But Beijing is doubly angry because it thinks Canberra has tried to stir up the issue overseas as well.

Then there is the issue of Huawei. The government has yet to rule on whether the privately owned, CCP-aligned telco can supply 5G technology for Australia’s mobile networks, but there is every chance Canberra will say no. That makes for another pothole in the road ahead.

Finally, no matter who is in power in Canberra, any Australian government will have to deal with the relentless strategic pressure that China is placing on every country in the region.

Trump continues to make life hard for US allies, and the sorts of things that Australia has done for decades, such as sending its navy into the South China Sea, will now come at a price. In such circumstances, there are no easy fixes.

Photo via Flickr user sharyn morrow