This is the first of several articles for The Interpreter by Lowy Institute Nonresident Fellow and former long-time Papua New Guinea correspondent Sean Dorney, who was in PNG for the elections as part of the Commonwealth's PNG Election Observer Mission.

The most surprising thing for me about the 2017 Papua New Guinea Election was the number of sitting MPs who were defeated.

No fewer than 55 were rejected by their constituents. At the time of writing one seat remained to be declared (Southern Highlands Provincial, where fighting not only delayed any result but also forced the counting to be shifted out of the province entirely). Of the other 110 seats, a few were not being recontested by the incumbent Member, so that figure of 55 means that just over half of the old Members who stood again were thrown out.

But, I hear you murmur, isn't this just typical of past PNG elections?

True, massive turnover has been a feature of elections in Papua New Guinea, but never before have sitting MPs had so much state money at their disposal. For the past few years they have had K15 million (A$6 million) each per year to spend in their electorates. The majority of this funding comes from one program, the District Support Improvement Program (DSIP). Those challenging the incumbents claimed to international observers that this created an uneven contest.

I was anticipating that such an enormous advantage would result in a significant change to that historical record of big turnovers and that well over half the outgoing MPs would win again. But no. Either many members did not spend the money properly (Queensland's real estate market was a likely side beneficiary of some MP spending), or PNG voters are smarter and less influenced by cash and project handouts than Prime Minister Peter O'Neill and I expected.

For O'Neill's party, MPs fared worse than the rest. His People's National Congress (PNC) lost 34 sitting Members, just over 60% of those who faced the voters. Only 21 were re-elected, but the PNC did win seven seats it did not hold before, and so wound up with 28 – almost double the number of the second-largest party in the new parliament, the National Alliance. Consequently, O'Neill was invited to have the first go at forming a government.

This election also witnessed the resurrection of the PANGU Party. Sam Basil was the only PANGU Member in the outgoing parliament, but he pulled in nine others this election – six of them from his own province, Morobe. Basil was one of only six MPs to win on first preferences. Of course, O'Neill did as well. William Duma was also successful on first preferences – his United Resources Party won ten seats.

Six other parties won multiple seats (from two to five each) and no fewer than 12 parties won just a single seat. A total of 14 independents won – all newcomers.

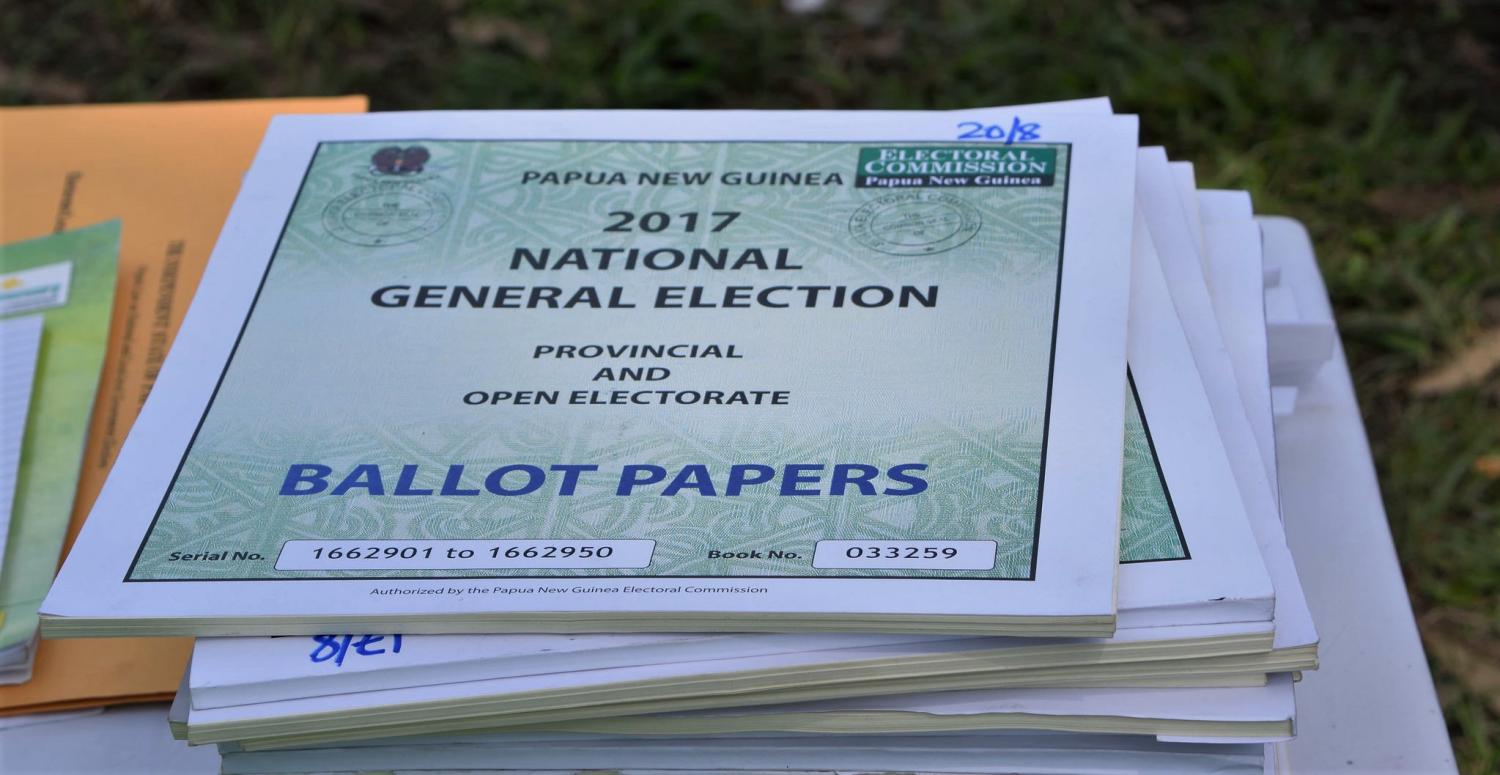

Under Papua New Guinea's limited preferential voting (LPV) system, voters have to nominate their first, second and third preferences for candidates they want to represent them in the parliament. One of the reasons counting takes so long is that in the vast majority of seats, very few of the leading candidates score even 20% of first preference votes. And with an average of more than 30 candidates per seat, the elimination of those at the bottom goes on and on until one candidate gets 50% plus one of the votes still in play.

For example, in the electorate of Karimui-Nomane Open in the Chimbu Province in the Highlands, there were 47 candidates. And while two mysteriously did not even vote for themselves (both recording zero votes), the remaining 45 candidates scored from one to 4485 votes. That leading candidate after first preferences was on just 11% of the 39,029 total valid votes.

As the eliminations of each successive candidate at the bottom continued, the preferences were distributed to those who remained. If the preferences went to candidates already excluded, then that vote was deemed no longer in play, or 'exhausted'.

In Karimui-Nomane, no winner emerged until only two of the 47 candidates were left. More than 22,000 votes had been exhausted before Geoffrey Kama of the Triumph Heritage Empowerment (THE) Party scrambled over the line with 54% of the remaining 16,832 valid votes. Kama wrested that seat off O'Neill's PNC. The outgoing PNC MP Mogerema Sigo Wei could manage only 4% of first preferences and, though he stayed in the race for quite a while, he was the 42nd candidate eliminated.

Some analysts have drawn attention to what has been described as large numbers of 'ghost voters' being added in seats the PNC held going into the election. If there were any in Karimui-Nomane, they did not help Mogerema Sigo Wei very much.

In a future article, I will discuss the state of the PNG's electoral roll and how parliament's 40-year-long refusal to allow any electoral boundary changes has led to wildly varying seat sizes and puts PNG at odds with its own laws and international best practice.