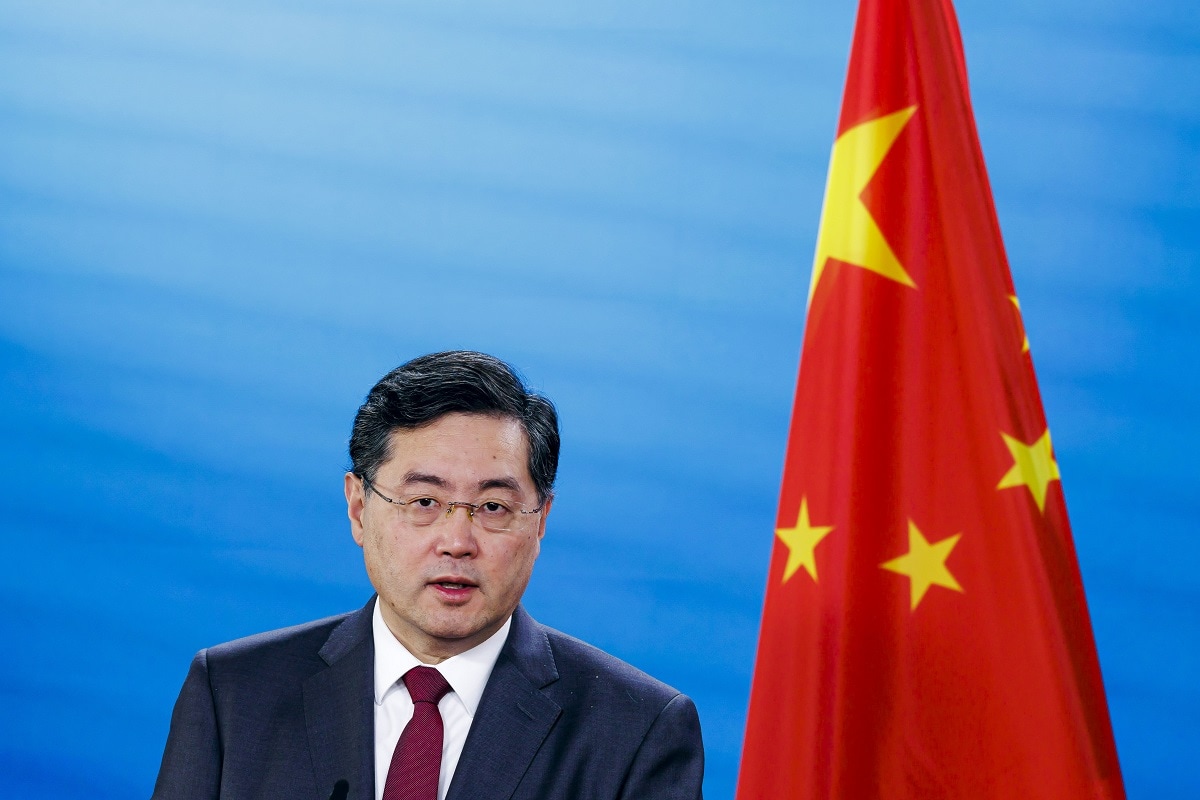

Qin Gang’s ouster as China’s foreign minister, as sudden as it was unexpected, reverberated around the world. One of China’s President Xi Jinping’s most loyal servants, Qin rose through the bloated Chinese Communist Party bureaucracy like a meteor, transitioning from a foreign ministry press officer to foreign minister in about a decade. Well schooled in the jarring “wolf warrior” diplomacy Chinese officials are now accustomed to, Qin would frequently point his finger at the United States for throwing the US-China relationship into the gutter even as he wrote in the American press about the importance of bringing relations back to a stable footing.

Then, it all came crashing down for him.

Whatever the reason for Qin’s removal, it’s unlikely to have much bearing on Beijing’s ties with Washington, which are riddled with systemic disagreements on issues as varied as export controls, territorial claims in the South China Sea, Taiwan and technology. The intrigue surrounding China’s former foreign minister is, in the grand scheme, a sideshow to the main event. And as best we can tell, the main event will continue to feature two superpowers talking past each other rather than to each other.

At best, Qin is a functionary. To the extent he had influence in Chinese foreign policy apparatus, it was due to his personal relationship with Xi, who propelled Qin to where he is (or was) today. Unlike in most countries where the foreign minister is a senior policymaker, foreign ministers in China don’t set policy – they implement the policies given to them by the Politburo Standing Committee, chaired by Xi himself. This is precisely what Qin did. His speeches and remarks are eerily similar to his predecessor, Wang Yi, who now chairs the Communist Party’s foreign affairs commission. Qin, in essence, was a mouthpiece, doing what his bosses back in Beijing wanted him to do.

Qin’s removal is an interesting story for scholars well tuned to how the Chinese system works (the general consensus is the episode reflects poorly on Xi’s judgement), but it’s a nothingburger with respect to whether it impacts China’s foreign policy in a major way. If there are changes, they will be at the margins. Xi, having consolidated power to an extent not seen since Mao Zedong in the 1960s, will continue to set the policy and trajectory of Beijing’s foreign relationships.

Indeed, if anybody thinks that Qin being out of the picture will help Washington and Beijing come to a mutually acceptable set of terms for their relationship, they are bound to be disappointed. The disputes between the United States and China are too numerous and comprehensive. The superpowers are operating on different wavelengths, more prone to preaching to each other about their respective shortfalls than doing the hard, necessary work of finding compromise on issues of mutual interest (climate change to name but one). In public, senior US and Chinese officials have a habit of painting one another as the sole impediment to a new, improved and more effective bilateral partnership – a never-ending game of one-upping that reinforces hardline elements on both sides.

Overall, the problem with US-China relations isn’t any one person – it’s the fact that the two countries have many national interests that are essentially incompatible. Combine this with mutually antagonistic perceptions and it becomes clear why the frosty ties are so difficult to thaw. Examples are numerous. Washington and its allies, including Australia, Japan and South Korea, remain disturbed by the People’s Liberation Army's (PLA) tendency to stake out territorial claims that are, at best, contrary to the so-called rules-based international order. Beijing is equally disturbed about Washington’s military posturing in the region. Every conceivable US action, whether it's the rotational deployment of B-52 bombers to northern Australia or the AUKUS pact, is depicted by Beijing as a US-led attempt to contain Chinese power or prepare for a regional confrontation over Taiwan. Biden administration officials frequently wave off China’s complaints as unjustified, emphasising that confrontation is neither inevitable nor desirable. But Xi, the one who really matters, doesn’t buy the US explanations and likely never will.

This isn’t to say that US-China relations are doomed. The two sides have engaged in a number of diplomatic encounters over the last three months, geared less towards solving problems and more on establishing communication channels that can endure after setbacks. CIA Director William Burns made a visit to Beijing in May to meet with Chinese intelligence officials. Antony Blinken followed up with a visit in June, becoming the first US secretary of state to land on Chinese soil in five years. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen did the same in July, as did former secretary of state and US climate envoy John Kerry. None of the sessions produced deliverables other than a pledge to keep talking, but even this low bar is a good sign that the relationship still holds some promise however faint it appears to be right now.

With or without Qin Gang in the picture, US-China relations will proceed as they currently are. America and China’s foreign policies appear immovable, drama over personnel notwithstanding.