Dick Woolcott was the best Australian diplomat of a generation. He was clever, hugely well informed, and perhaps the nicest man you’ll ever meet. He was to me a mentor, and a friend. Indeed, Woolcott was someone who never lost a friend, and the number of his friends, at home and abroad, was phenomenal. He died last week, aged 95.

As an ambassador, Woolcott was without peer. He enjoyed life under any and all conditions. Posted early as a head of mission to West Africa in 1967, he made a quick impact with his great good will and entertaining personality. That of course was not always appreciated back home, when his “leaked” (we all knew who did it) despatch on the inauguration of the President of Liberia appeared in the Bulletin magazine – a classic in humorous reporting, unfortunately rarely seen in foreign affairs missives, and later reproduced in his 2007 book Undiplomatic Activities.

Woolcott loved all his postings. Perhaps Manila was his favourite – what’s not to like after all amidst the unreal world of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos? He and his wonderful wife Birgit certainly made the best of handling the personal and professional stresses of working in that eccentric regime. As an idea of Woolcott’s capacity to keep friends and inspire staff, even decades after his time in Manila, his staff from the embassy from then still met every year for a party to celebrate his birthday. His 95th, last year, was huge.

Jakarta in the 1970s was probably Woolcott’s most challenging posting, particularly as concerns East Timor and the Indonesian invasion. This has been extensively covered, again recently, but the point I want to make is that it showed how Woolcott made an assessment of Australia’s national interest and stuck to his conclusions through a welter of criticism, some of it very hostile and personal. His personal account of this issue in his 2003 memoir The Hot Seat, which also reproduces the cable he sent to Canberra at the time, is a must for any student of Australian diplomacy.

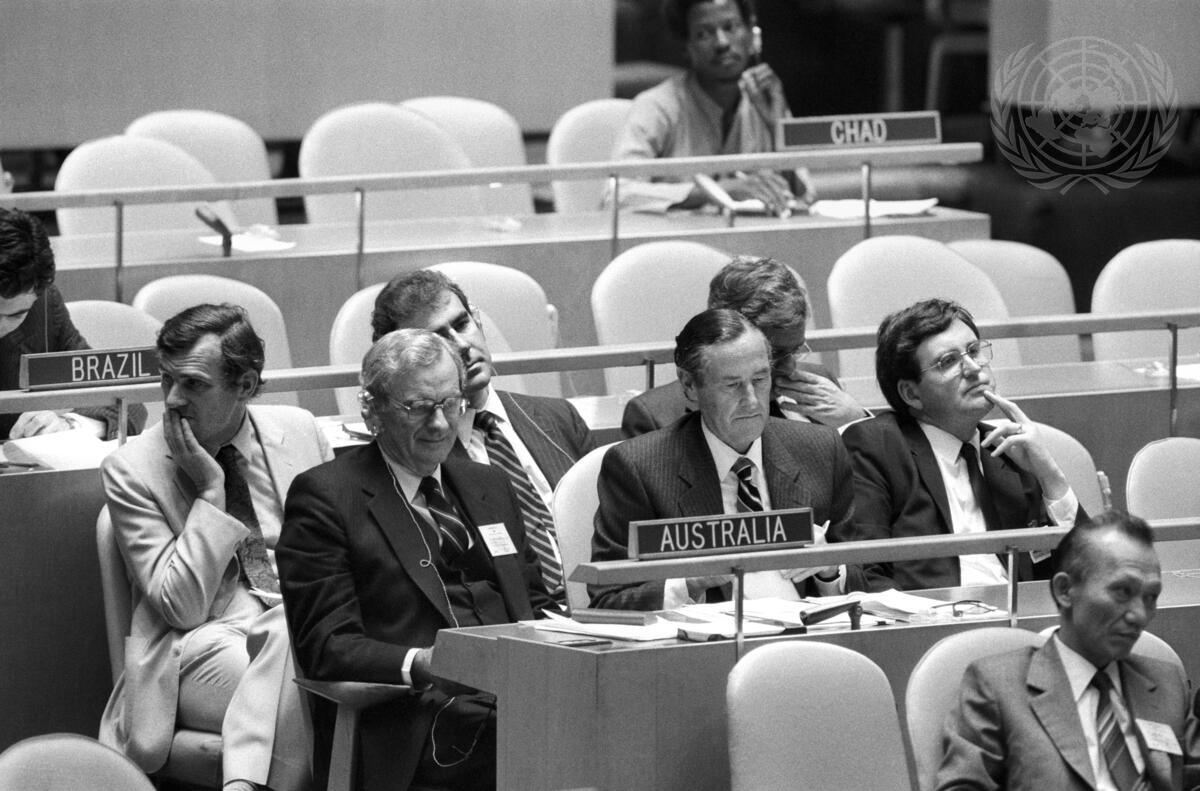

The United Nations in New York is a tough gig for any ambassador; highly competitive, full of outsize egos and self-promoters. Woolcott was most unusual in his six or so years there, in that he had not just the respect of the other representatives, but also of the UN staff and so many visitors for the multitude of meetings held at the headquarters. Other ambassadors would often say something along the lines of “Well, I’ll do it for Dick then”. When I was working through New York many years later, l was still often asked by envoys from all continents how Woolcott was going.

The preceding is all about Woolcott as an Australian ambassador overseas, but it was in Canberra where his greatest recognition was achieved. Not many senior officials could have passed so seamlessly through a list of prime ministers from Robert Menzies and Billy McMahon to Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke. Woolcott would play squash with McMahon; hit him on the forehead, the story goes. He accompanied all of them on some or all of their overseas trips. His contacts and friendships, throughout Asia especially, were of enormous benefit to political leaders, few of whom had experience of the region.

Woolcott’s time as Secretary of Foreign Affairs and Trade from 1988–92 came at a difficult moment in that Department’s evolution. He had to handle the amalgamation of the previous Department of Foreign Affairs and the Department of Trade – two departments with a longstanding shared history of contact at home and overseas but also, to put it politely, of personal and political rivalry. Neither had sought nor knew about the amalgamation idea and none of the senior or not-so-senior staff favoured it. Regardless, that was the decision of the (re-elected) government and was to be implemented immediately. Former Department of Trade staff were moved holus-bolus into new rooms at DFAT, a new organisational structure was brought in, and staff were told to live with it. Frankly, it was a very difficult transition, and Woolcott as Secretary had to bring it about and take it forward. Without the charm of his personal qualities, and the trust that the ex-DFA staff had in him, the integration process would have been very much more disruptive.

In Canberra, and even while still a junior officer, Woolcott embraced the concept of dealing openly and honestly with the media. He was the first Public Information Officer and built a wide range of close and confident relationships with journalists, foreign correspondents and editors. He maintained these contacts throughout his career.

A final story about Australia’s efforts in the region, and Woolcott’s part in it, is memorable – his role in the formation of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. This was a sudden brainchild of then Prime Minister Hawke, who knew that Australia needed to do more, much more, to beef up its standing in Asia. Unfortunately, the idea was not well prepared. It came up in Hawke’s plane en route to an Asian regional leaders’ summit meeting in Seoul, perhaps a result of some ideas-shopping with his staff on board. Hawke chose enthusiastically to launch it then and there to the gathered Asian heads of government. Needless to say, they felt they had been caught short, even ambushed, by this big new idea. The reaction in Seoul was of course “we’ll study this carefully and discuss it with our governments”, which is diplomatic-speak for don’t call us we’ll call you.

Hawke was surprised by this reaction, being more used to much more favourable (and easy) endorsements of his big ideas at home. And at home, the reaction in private from the Foreign Affairs Department and from many of Hawke’s fellow ministers was not just surprise but hostility, less to the idea itself but more to the unprofessional and indeed self-defeating way it had been launched. A proper diplomatic initiative needs to be carefully worked up and shepherded through national governments before being sprung in full bloom to national leaders.

As several, probably most, Asian governments started to back away definitively, Hawke to his credit realised that something had to be done and quickly if Australia’s diplomatic standing were not to suffer a public humiliation.

That “something” was Dick Woolcott. Hawke summoned Woolcott very smartly on his return to Australia, knowing Woolcott’s personal standing around the region, and told him essentially to go out and fix it. Talk to the heads of government, see what can be done to stop them from vetoing the idea from the start, but also use the authority to adjust the proposal as necessary and to get it on its way. It was made clear to Woolcott that there would be consequences if he failed, rather along the lines of the encouragement of the Spartan warriors – come back with your shield or on it.

Woolcott’s success was phenomenal and was the essential ingredient in the formation of what is now APEC. It was a tribute to Woolcott’s ability to foster friendships, and I heard from many contacts at Australia’s embassies in the region that in several cases the reply was – again – along the lines of “Well, we’ll do it for you, Dick”.