I’ve worked a lot in development areas, but I have never run a charity before. So, when I decided to set up a locally based international aid and development not-for-profit, it was with as much fear as hope.

As an ex-player, I turned to football (soccer). The world’s leading team sport by numbers, football has around 250 million registered players. If the world’s registered football players made up a country, it would be about the fourth largest. So when I decided to take football to Rohingya refugees in Malaysia on behalf of my charity, there was plenty of evidence to suggest it would be of value.

What I learned was sobering.

Dubbed by many “the Rohingya national team”, they became a symbol of ethnic pride in Malaysia and the diaspora, as well as inside Myanmar.

Our charity managed to secure a small grant and we started our Rohingya Football Club program in early 2017. The program’s aims were to support the club and to generate support both within the Rohingya communities (those in Malaysia and those outside Malaysia) and among non-Rohingya. Ours was a rights-based approach that sought to generate participation, empowerment and accountability in a two-way relationship that ensured a mutual understanding of expectations and outcomes.

The challenges were significant and may offer some insights into problems the Rohingya may have in being heard in an international context. Not all problems are easily solved, nor perhaps should they be “solved” at all. But the experience provides insights into managing privately delivered international aid deployments in the current context.

The major point can be summarised as follows.

Safety concerns

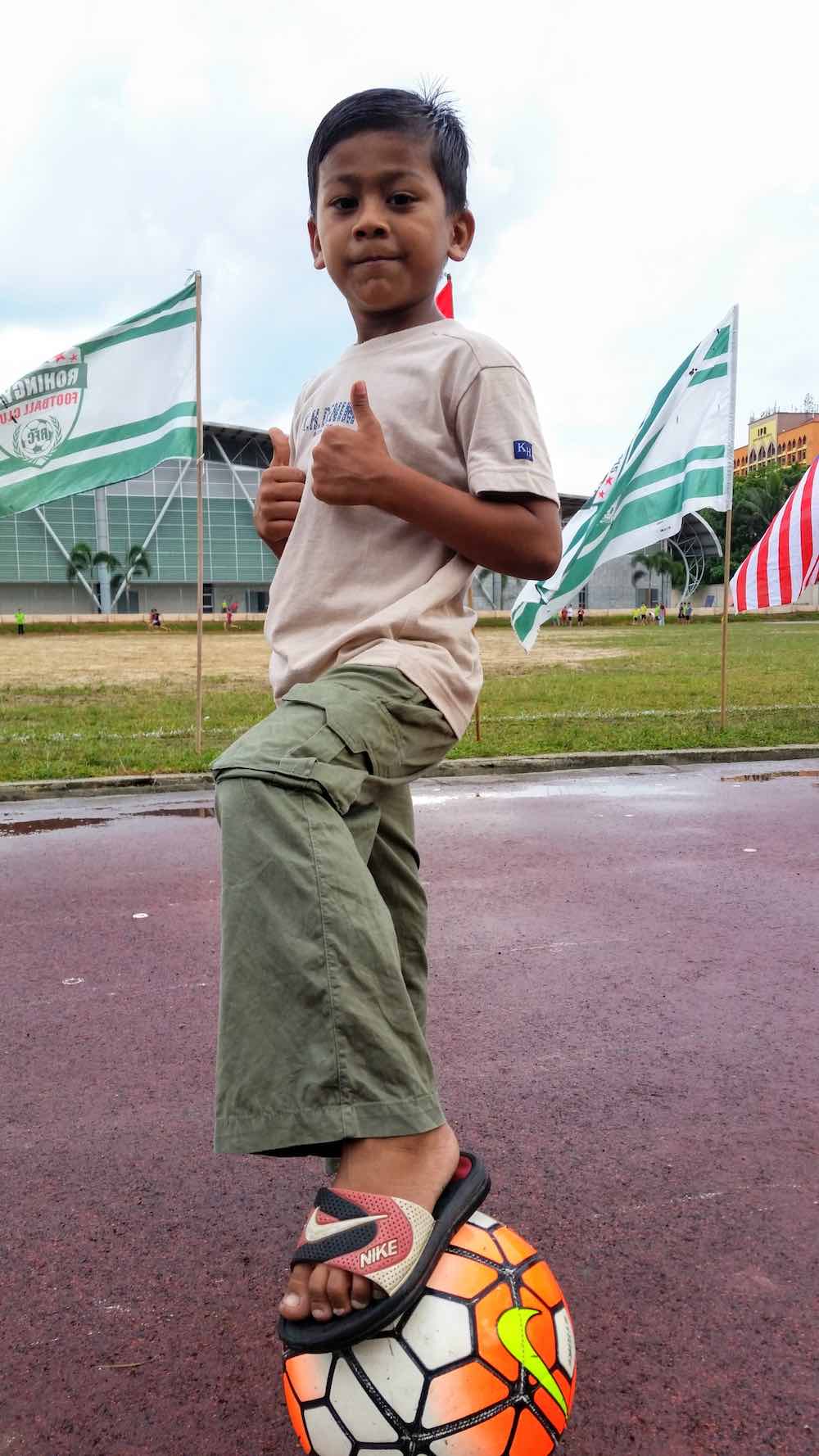

The RFC targeted the local Rohingya community in Kuala Lumpur, and, in particular, sought to give children and youth access to sporting resources. However, the high incidence of kidnapping (literally kids, as children were often the targets) and child abuse in a setting where Rohingya were often denied access to proper security or legal protection ensured children were rarely seen at RFC games, and parents would not let them play sports.

Many Rohingya children, at least in KL, spend much of their time indoors or close to where they live.

While this situation is understandable, such limited access to, in our case, a core aid cohort, meant we could not fully fulfil our charity goals.

Gender issues

Our intention was to incorporate women and girls equally into the broad RFC. This was blocked to some extent by the politics of gender in a traditional social structure, in which men saw the involvement of women as detrimental to their own ability to attract resources. We were led to believe that Rohingya men thought women would effectively steal funding away from the men’s activities, rather than increase the overall funding pie.

Our strategy to give the men a team first and then to introduce a women’s sports section was designed to head off some of the gender dynamics we were led to expect. This was largely unsuccessful.

Women community leaders whom we had worked with reported they were uncomfortable and felt marginalised and even pressured by men in the RFC.

We never really solved the gender discrimination problem, and this was a central factor in ceasing our involvement with the RFC.

Media inexperience

An academic friend who had worked with many refugee groups in Southeast Asia told me early on that the Rohingya are “not really media friendly”.

Being a media person, I knew that could mean a few things.

As it turned out, he meant that many Rohingya don’t present as “good charity recipients”. This has to do with the way aid is marketed and sold. The receivers of aid are generally depicted as smiling and healthy, bolstered and enlivened by the generous largesse of donors. It’s what I call the “brochure approach” to charity.

Rohingya are not “trained” in media presentation. They often look sullen and dour, even when receiving aid. Women and children (as noted) are rarely seen. While I don’t blame them for this, especially given what they’ve been through, nor make unnecessary cultural judgements about it, this image did make it harder to “sell” them to possible donors.

This is an aspect of aid and charity work which I find both confusing and distasteful. But the fact is that “happy sufferers” get more funding. It’s a disconcerting reality.

Diaspora politics

It became evident that the Rohingya are, like any other group of human beings, not immune to political division.

In the diaspora, the vast majority of which is refugee-based, mainly Rohingya men jostle and compete for space and a voice. They set up as leaders of their community and seek the obvious localised benefits that come with that. But they also pursue leadership status to represent their community more widely, including to aid donors.

In a situation where there are no governments or institutions as such, finding the “correct” leader can be a difficult process.

The local Rohingya organisation with whom we worked was a good call for us, as they had an established leadership position with the Rohingya community in KL and beyond.

But I was aware of tensions and of competing groups, some of whom contacted me, fairly pointedly imploring support for their own “Rohingya Football Club”.

Overall, our Rohingya Football Club experience concluded successfully, albeit with adaptations to the original program. The club received a lot of media interest, which led to their story being told across the world in at least four different languages. Further, the RFC achieved membership status with the Confederation of Independent Football Associations, which holds a periodic world cup for stateless nations.

The RFC played a number of games under our assistance with fellow Rohingya and with local non-Rohingya teams, including government institutions such as the local police, and this clearly aided community cohesion and networking.

Within the Rohingya community itself, social media data and anecdotal evidence suggests the club has become a well-known focal point for Rohingya – dubbed by many “the Rohingya national team” – and a symbol of ethnic pride in Malaysia and the diaspora, as well as inside Myanmar.

However, lessons learned from our setbacks and challenges may assist in developing the positive momentum we sought to generate for the Rohingya people.

I would hope that our story can help give the role of grassroots sport in general, and football in particular, more prominence in the overall aid, development and post-conflict mix, where it is currently, in my view, vastly undervalued.

Many government-led aid programs have tilted towards sport in recent years. But this has often been via elite athletes and high-profile sporting events, rather than at the grassroots level, where I would argue it is likely to have the most impact.

JJ Rose is founder of a registered charity seeking to bring organised sports to disadvantaged communities worldwide. The RFC program was the charity’s pilot project.