Unrest is roiling Russia’s near abroad, from its western flanks in Europe to the “’Stans” of Central Asia on China’s doorstep. For all their local particulars, these nations share a common historical legacy which continues to undermine stability in various ways.

In Belarus, President Alexander Lukashenko is fighting for political survival. The autocrat has ruled the country since 1994, using his ruthless security forces to crush any dissent. Lukashenko’s landslide victory in a discredited Presidential election in August has, however, brought thousands of angry Belarusians out on the streets of Minsk to protest, prompting a violent regime crackdown.

Popular opposition to Lukashenko has grown, reflecting mounting economic hardship. Belarusians are weary too of the pervasive stagnation of their tightly controlled Soviet-style society.

But what happens in Belarus will ultimately be determined not by Lukashenko, but by his key ally and economic backer – Russia.

The unrest now in Belarus, South Caucasus and Kyrgyzstan will test Moscow’s ability to maintain a firm grip on its neighbourhood.

There is no love lost between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Lukashenko. Moscow has tired of the Belarusian leader’s bombast and unpredictability: Lukashenko fitfully lambasts and distances himself from Russia, yet repeatedly importunes the Kremlin for economic bailouts.

After initial hesitation, the Kremlin has thrown its weight behind Lukashenko, promising security and economic assistance.

Belarus is vital to Russia’s national security: maintaining stability and an amenable regime, compliant with Russian interests, is paramount. But Moscow must tread carefully. The Belarusian protests have – so far – been internally focused, seeking Lukashenko’s departure. If Moscow provides overt support for Lukashenko to put down the protests or exploits events to drive closer political and economic integration with Belarus, it risks provoking anti-Russian sentiment – not to Russia’s longer-term advantage.

Eventually, Russia would probably prefer an orderly transfer of power in Minsk to someone able to restore stability in Belarus while still being acceptable to Moscow. Meanwhile, they are stuck with Lukashenko. Moscow will urge him to swallow his pride and talk to his opponents, seeking to divide the opposition and defuse the protests. But if the unrest worsens, Russia will not stand in the way of attempts by Lukashenko to restore order forcibly.

In the south Caucasus, renewed fighting has broken out between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

In 1988, the majority ethnic Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh took advantage of crumbling Soviet authority to break away from Azerbaijan, triggering war between the two countries. A fragile ceasefire has prevailed since 1994, punctuated by periodic armed clashes. Efforts to resolve this intractable conflict have failed, confounded by the bitter emotions driving both countries.

Azerbaijan is intent now on regaining Nagorno-Karabakh. It has been further emboldened by strong support from Turkey.

Turkey’s involvement brings wider geopolitical risks. It challenges Russia’s traditionally dominant role as regional arbiter. Turkey’s assertive stance may also increase pressure on Moscow to assist Armenia, its treaty ally. It complicates Moscow’s already awkward relationship with Ankara, with the two powers at odds over Syria and Libya. Iran too has an interest, given its shared borders with Azerbaijan and Armenia, and its large Azeri community. The conflict also threatens key oil and gas pipelines running from Azerbaijan through Georgia to Turkey.

To the east, unrest has broken out in Kyrgyzstan, following disputed parliamentary elections.

Political instability has long plagued Kyrgyzstan, where two Presidents have been overthrown by popular revolt since 2005. Kyrgyzstan’s efforts to develop a functioning democracy have been undermined by factional rivalries, regional divisions, endemic corruption and economic weakness.

Instability in Kyrgyzstan raises wider concerns, given its strategic location and abundant natural resources. China and Russia have substantial economic interests in the country, while Moscow has a military base there.

There is a common thread running through all this regional unrest: unfinished business from the break-up of the Soviet empire.

Belarus has never abandoned the authoritarian and state-run economic model of the Soviet era – the consequences of which it now has to confront. Armenia’s enmity with Azerbaijan (and Turkey) is long-standing, but the seeds of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict were sown by the Soviets in the 1920s, who inserted the territory as an autonomous entity within Azerbaijan. Likewise, tensions within Kyrgyzstan, and between Kyrgyzstan and its Central Asian neighbours, reflect the arbitrary delineation of borders in Soviet times.

These are not the only residual issues arising from the demise of the Soviet empire. Relations between Uzbekistan and adjacent Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan remain tenuous, strained by ethnic, border and water disputes. The status of Transnistria, the sliver of Russian-garrisoned Moldovan territory wedged between Moldova and Ukraine, remains unresolved.

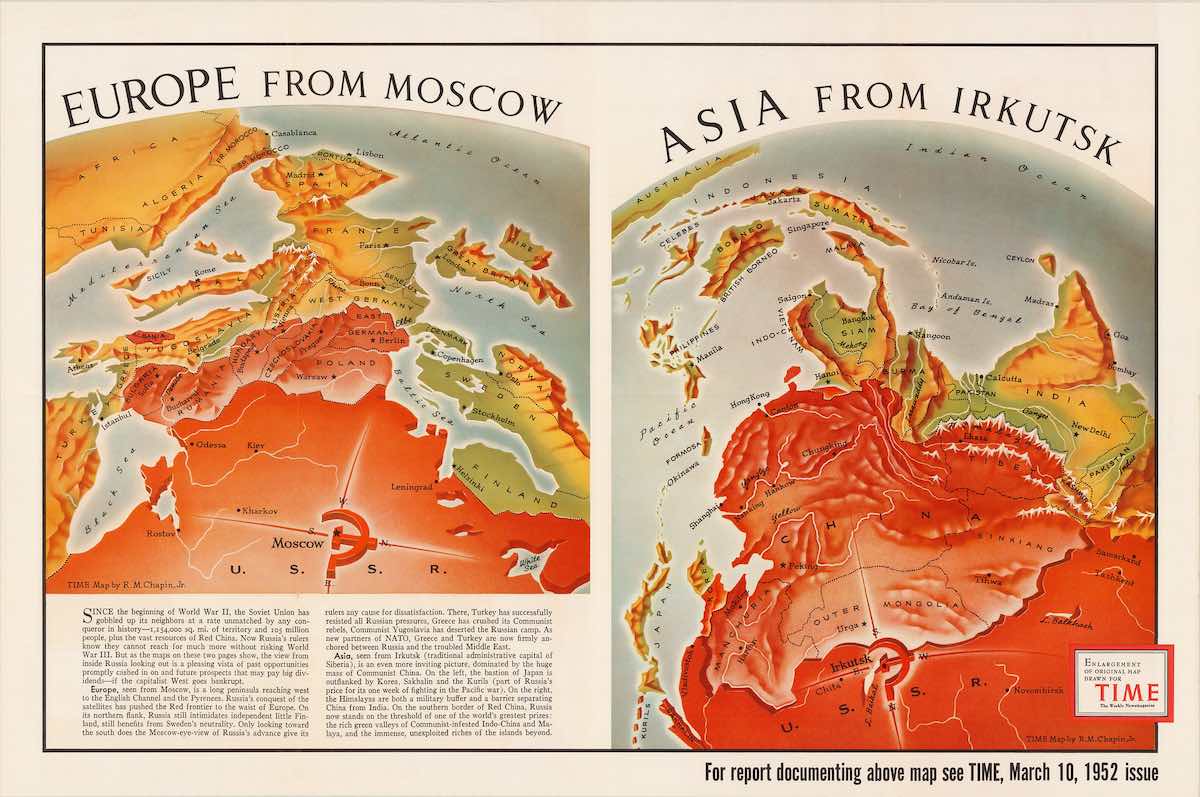

Putin has implicitly asserted Russia’s entitlement to a sphere of influence around its periphery – a stance which prompted Moscow’s interventions in Georgia and then Ukraine, and its unease at NATO expansion into the Baltic republics. The unrest now in Belarus, South Caucasus and Kyrgyzstan will test Moscow’s ability to maintain a firm grip on its neighbourhood. This is exacerbated by the growing influence of others in the region, especially China and Turkey, as well as the gravitational appeal of the European Union for states such as Belarus and Armenia.

Moscow will need to respond deftly to protect its interests and retain influence in these countries, without generating counterproductive anti-Russian reactions.

The problems around Russia’s periphery are not going away anytime soon. For the Kremlin, so anxious to assert its dominance over its near abroad, it may become a matter of “be careful what you wish for”.