“If you want peace, prepare for war.” The idea that states can avoid war by strengthening their military is attractively simple, and the advice, attributed to Roman author Vegetius, has proved enduringly popular. In modern strategic lingo, it’s embodied in the buzz word “deterrence”.

Deterrence assumed centre stage in Australia’s ground-breaking 2020 Defence Strategic Update. This replaced the 2016 Defence White Paper’s “Strategic Defence Framework” with three objectives:

- to shape Australia’s strategic environment;

- to deter actions against Australia’s interests;

- and to respond with credible military force, when required.

The Defence Stategic Update is not very specific about what must be deterred or how this will be achieved. The “what” is “actions against Australian interests” which includes “actions that undermine regional resilience and sovereignty” and “coercive or grey-zone activities”. The “how” includes “capabilities to hold adversary forces and infrastructure at risk further from Australia, such as longer-range strike weapons, cyber capabilities and area denial systems”. Although the document does not specify who needs to be deterred, everyone knows that the Defence Stategic Update was prompted by the growing challenge posed by China.

Whether or not China is deterred from a particular action will depend on Beijing’s cost-benefit analysis.

Mixing and matching these whats and hows yields statements that are either implausible (“Australia will deter China from actions that undermine regional resilience and sovereignty by threatening Chinese infrastructure with longer-ranger strike weapons”) or too general to be useful (“Australia will deter China from actions against Australian interests by using cyber capabilities”).

There are, of course, good reasons why Australia would not want to openly specify what might cause it to attack Chinese targets. But this reticence is not confined to carefully crafted official statements. Much of what is written and said about deterrence is similarly unclear. Australia’s objective is rarely defined more tightly than to “deter the Chinese from acting in ways that are inimical to our goals or threating to our interests”. Vague terms like “deterrent assets”, “deterrent capability” and “deterrent effect” are sprinkled liberally through much analysis.

Getting more complicated …

Deterring other states from military (or other) action has always been more complex than the advice from Vegetius would suggest, and it is getting more so.

Whether or not China is deterred from a particular action will depend on Beijing’s cost-benefit analysis. That will be informed by its assessment of its opponent’s capabilities as well as their intentions and resolve. On all these points, Beijing’s subjective assessments may be very different from, for example, Australia’s. China might see Australian preparations to defend itself as preparations to attack China (the so-called “security dilemma”). And China is more likely to reach this view if Australia seeks to deter it by threatening retaliatory strikes (deterrence by punishment) rather than by simply making it harder for China to attack Australia (deterrence by denial).

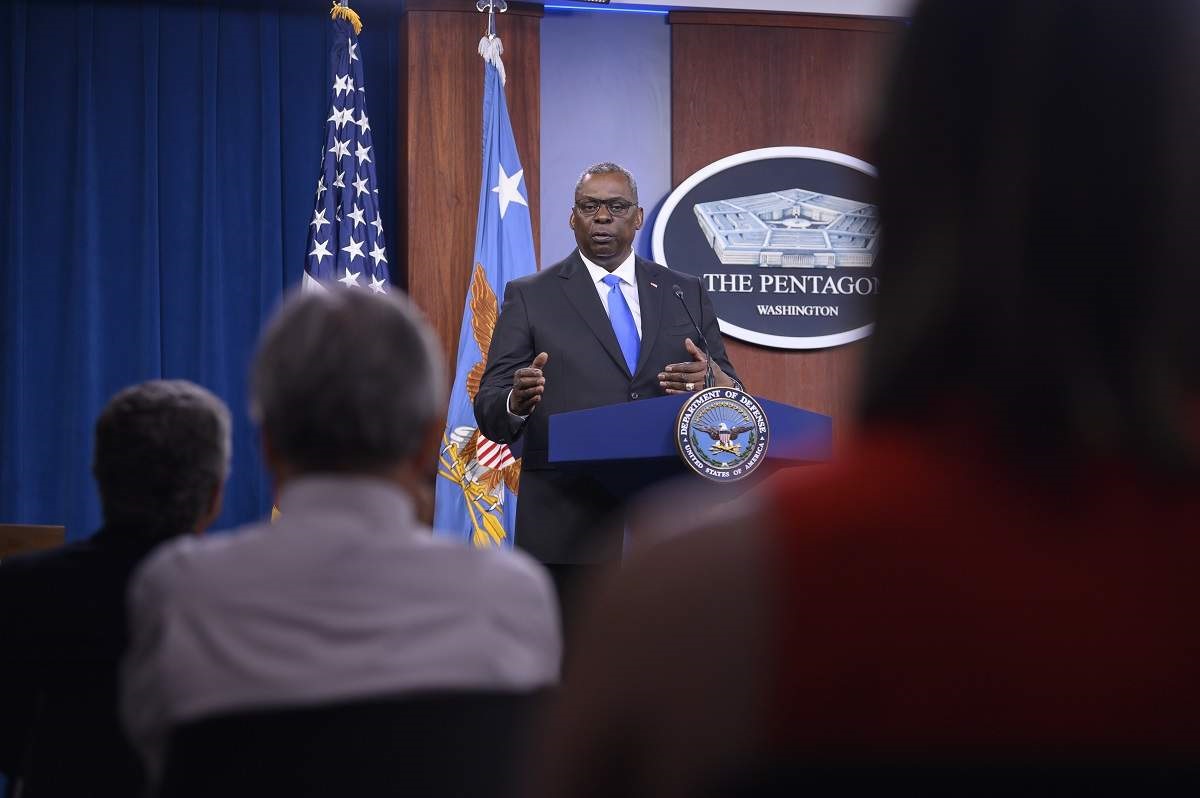

US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, pictured during a press conference in the Pentagon Press Briefing Room, Washington, DC on 21 June, has described his country’s approach as “integrated deterrence” (US Air Force Staff Sgt Brittany A. Chase/US Secretary of Defense/Flickr)

Deterrence is getting even more complicated because the field of inter-state competition is expanding. Classical deterrence theory was developed in response to the emergence of nuclear weapons. States are now putting more effort into seeking advantage through means short of war. China and Russia have proven adept at actions that, though assertive, are not aggressive enough – or are sufficiently deniable – to provoke a military response. For example, Russia may be deterred by the US military from launching a military attack on the United States, but not be deterred from meddling in US elections. This so-called “grey-zone” includes increasing competition in cyberspace, where deterrence is especially complex because of difficulties both in attribution and in distinguishing offensive from defensive measures.

The US response to this complexity appears to be to formulate a more complicated concept of deterrence: “integrated deterrence”. In the words of US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin:

“[W]e’re operating under a new 21st century vision that I call integrated deterrence. Now, integrated deterrence means using every military and non-military tool in our toolbox in lockstep with our allies and partners. Integrated deterrence is about using existing capabilities, and – and building new ones, and deploying them all in new and networked ways – all tailored to a region's security landscape, and growing in partnership with our friends.”

Rather than formulate more complex theories, national security planners should aim for clarity.

A whole-of-government approach that includes allies and partners is a sensible goal. But Austin doesn’t describe what will be deterred or how. That detail might exist in other documents, but experts who claim to have ready everything written on “integrated deterrence” are none the wiser as to how integrated deterrence differs from deterrence.

… so keep it simple

Rather than formulate more complex theories, national security planners should aim for clarity by applying a simple rule: anyone advancing a proposition about deterrence should be required to do so in a single sentence that identifies who is deterring, who will be deterred, what they will be deterred from, and how they will be deterred. “Deter” should appear only as a verb. Noun formations such as “deterrent assets”, “deterrent capability” and “deterrent effects” should be banned. This would compel clearer thinking about what is being attempted and enable better assessments of its viability.

It could also improve messaging. Public statements need not be as stark as those prepared for planning purposes, but the government should speak more plainly about the what and how of deterrence. To contract the “grey-zone” and expand the rules-based order, Australia and its allies need to be clearer about what the norms are. By collectively clarifying their own intentions and coupling any threats intended to deter with reassurances about the benefits of alternatives they will have a better chance of influencing China.