As the coronavirus ravages the globe and smashes supply chains, Singapore has been held up as the gold standard of containment. So far, the virus has only claimed three lives in the city state, which has won widespread praise for its thorough testing regime, meticulous contact tracing system, and clear public-health messaging.

But if Singapore is well-positioned to tackle the threat, it also has a vulnerability which is unique in Southeast Asia – a proportionally large and growing pool of older people.

If the pathogen is not well contained, it is often the elderly who bear the brunt. As Italy’s horrifying battle with the coronavirus vividly demonstrates, it can quickly take a terrible toll on rapidly ageing societies.

And while prosperity has delivered Singapore many gifts, children are not among them.

Why should Singaporeans continue to strive for their future if their nation gradually evolves into little more than a polyglot playground for global elites and their families, staffed by an ever-growing army of temporary workers from poor countries?

As Singapore has grown wealthy, its fertility rate has plummeted. When the country embraced independence in 1965, it was 4.66 – meaning that on average women had between four and five babies in their lifetime. Singapore’s leaders, seized with anxiety about overcrowding in its slums and villages, embarked on a massive birth-control campaign – “Stop at Two!” – to bring that number down.

It worked. But now the pendulum has swung dramatically in the opposite direction, and many young Singaporeans are deciding not to have children at all. The fertility rate is a dismal 1.14, well below the 2.1 needed to sustain a population without immigration, and among the lowest in the world. “Stop at Two!” now feels like an echo from an ancient era.

For the last two decades Singapore’s government has plied young couples with incentives to have more babies: paid maternity leave, cash grants, childcare subsidies, tax cuts, and flexible work arrangements. It’s also allowed Singaporean families to employ low-paid domestic helpers from poorer countries to assist with child-minding and housework.

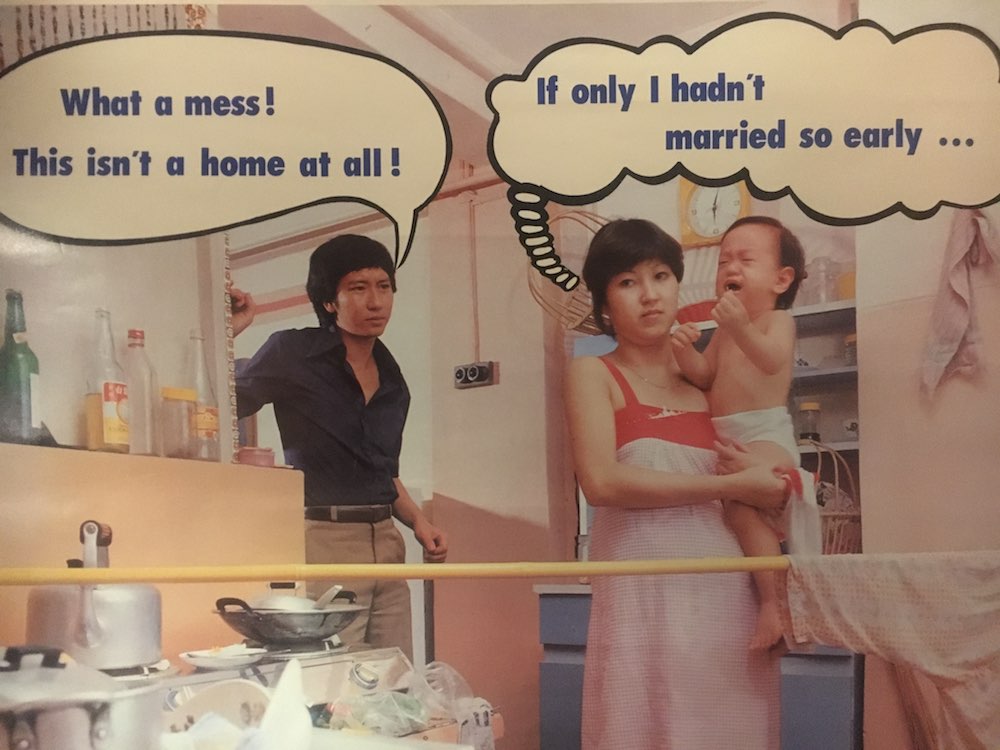

There have even been a slew of public campaigns encouraging young couples to do their patriotic duty – ranging from the determinedly wholesome to the excruciating.

But nothing is working. The trend line still points south. That means ageing Singapore – like many developed countries – is facing a demographic time bomb. Fewer kids now means fewer future workers who can support the vast ranks of greying Singaporeans in retirement. Over time this puts an intolerable strain on national budgets and services.

Of course, politicians and bureaucrats have one powerful solution: immigration. Singapore is orderly, well-governed, and blessed with excellent infrastructure, hospitals, and schools. It will never struggle to attract new citizens. Millions of foreigners have flocked here over the last few decades, and many have stayed permanently.

Singapore’s population is now around 5.7 million people, but only 3.5 million of them are citizens. Another half a million are foreigners with permanent residence, while a further 1.6 million are temporarily working or studying in the country.

This influx of people not only brings in crucial talent but also staves off demographic disaster, providing the workforce needed to keep the whole national enterprise afloat.

But large-scale immigration also brings tensions. There are no significant nativist movements in Singapore’s tightly controlled political ecosystem, but there are fairly constant complaints about the strain all these new people have put on the republic’s trains, hospitals, and schools. Some opposition MPs are quick to stir these resentments. Many in the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) still blame their setbacks at the 2011 election on popular frustration over mass migration.

At times, there is a racist tinge to this anger. As a small state with giants on its doorstep, Singapore feels its vulnerability keenly. Some Singaporeans worry their distinctive syncretic identity – neither Chinese, nor Indian, nor Malay – could quickly be submerged if they become a minority in their own country.

And while Singapore’s political elite is quick to stifle any outbreaks of racial hostility, it also shares some of these anxieties.

“To secure our future, we must make our own babies, enough of them,” Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong told a business conference last year.

Because if all of the next generation are not our own, then where do they come from, and what is the point of this?

Lee was not pressing the panic button, nor was he flagging big cuts to immigration, which he called a “plus” for Singapore. He told the audience that if the city state could just nudge up its fertility rate to 1.3 or 1.4, then it could strike a good balance, keeping the current migration rate steady while retaining a distinctively Singaporean “core.”

But Lee’s rhetorical query – “(then) what is the point of this?” – shows how quickly demographic questions can become existential. Why should Singaporeans continue to strive for their future if their nation gradually evolves into little more than a polyglot playground for global elites and their families, staffed by an ever-growing army of temporary workers from poor countries?

And right now even the modest baby bump sought by Lee feels like a near-impossible task.

Fertility policy expert Tan Poh Lin, from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, suggests that Singapore’s current dilemma has deep roots in its culture. Singapore’s rapid economic growth has been powered by its formidable focus on education and hard work. Both its workplaces and its schools can be fiercely competitive. Tan says that means most young Singaporeans are more focused on their careers than starting a family. Simultaneously, those who do say yes to children only have one or two, so they can invest the time and money needed to ensure they succeed at school and beyond.

“Singapore’s human capital success story, which has propelled it to the top of international rankings, thus comes at a cost to its people’s willingness and ability to build families,” she writes.

The inability to raise the fertility rate is hence not so much a testimony to ineffective pronatalist policies as to the overwhelming success of an economic and social system that heavily rewards achievement and penalizes lack of ambition.

Tan argues that Singaporean policymakers might still be able to lift the birth rate slightly, partly by focusing incentives more tightly on younger women in their peak childbearing years.

But time is running out. As Singapore’s population gets older, a feedback loop forms. There are fewer and fewer couples of childbearing age, which means any increase to the fertility rate will deliver smaller and smaller returns over time.

Or as Tan puts it: “it’s now or never.”