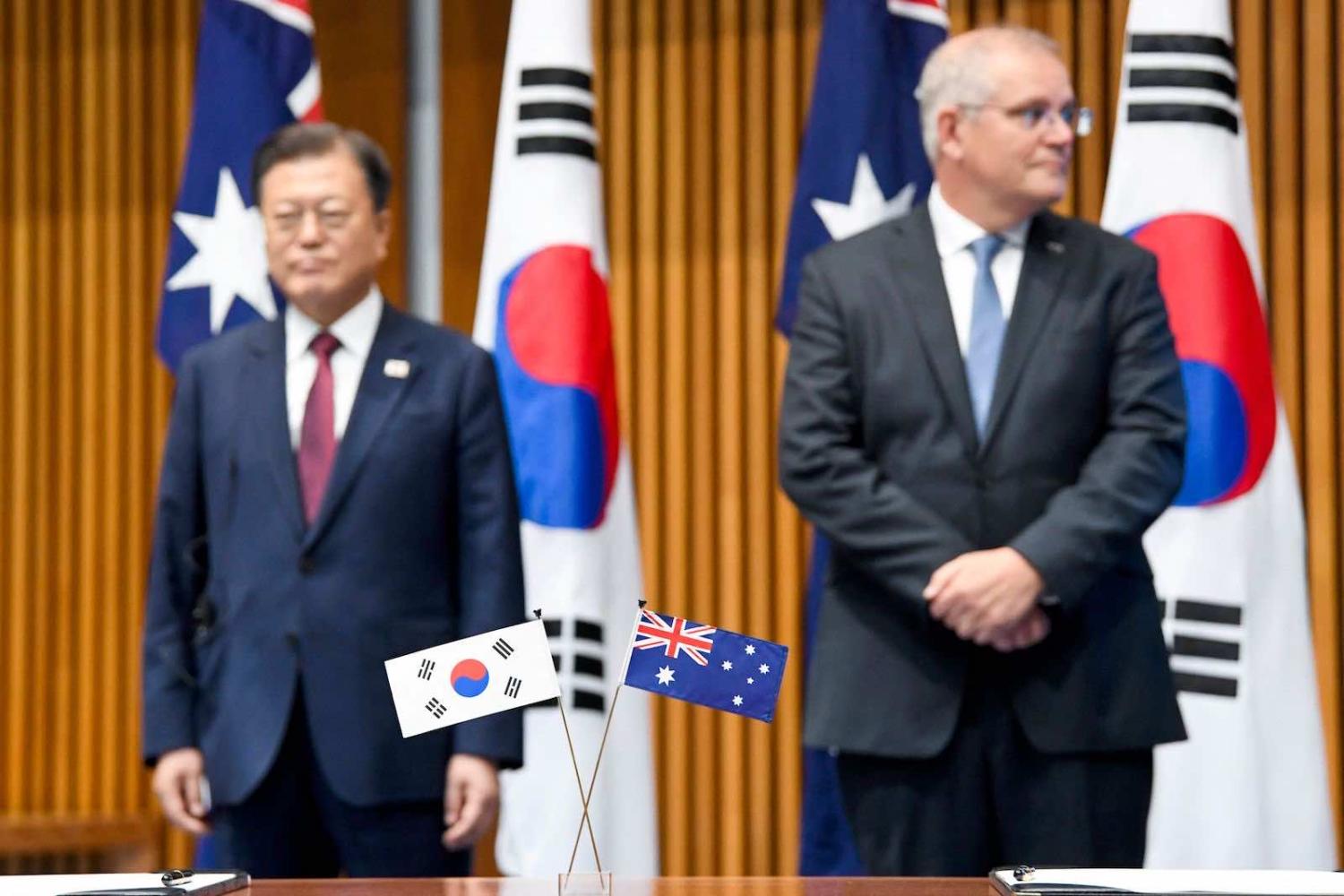

The elevation of a “comprehensive strategic partnership” between South Korea and Australia during South Korean President Moon Jae-In’s state visit last month has left analysts torn about its impetus. Is South Korea simply seeking to expand economic ties? Or are we witnessing a “quiet alignment” with Australia against China’s assertive behaviour in the region?

While both explanations may hold slivers of truth, it would be mistaken to think South Korea’s sole strategic occupation is China. More so, South Korea’s attitudes are shaped by its fractious relationship with its closest neighbour – Japan.

While global attention has remained transfixed by China-US tensions, for the past several years South Korea’s relationship with Japan could only be described as catastrophic. Marked by festering historical tensions and cut-throat economic rivalry, the two countries have been embroiled in an escalating trade war since 2018 – which continues to threaten crucial global supply chains. That year a South Korean Supreme Court Ruling ruled Japanese companies must compensate former victims of forced labour during the Second World War, prompting Japan’s then prime minister Shinzo Abe to launch a series of trade restrictions against South Korea’s export-orientated economy.

Japan’s actions have not only made it difficult to conduct two-way trade by removing South Korea from its so-called “white list” – requiring individual checks on more than 800 “sensitive” exports – but have also denied South Korean companies of high tech materials needed to produce memory chips, semiconductors, telecommunication products and security technologies. The punitive measures sparked a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment in South Korea and sparked frenzied efforts by the Moon administration to secure and diversify its supply chains. Yet, after three years of coordinated efforts to wean off Japanese exports, South Korea’s trade deficit with Japan actually widened by 9 per cent in 2020 and by 31 per cent in the first six months of 2021.

More than economics, however, South Korea and Japan’s deteriorating ties have also spilled into the military arena. Days after Tokyo’s punitive economic measures, Seoul threatened to cancel an intelligence sharing pact – known as the GSOMIA – which is seen as essential to defence cooperation against regional threats such as North Korea and China. Although Seoul conditionally held back its cancellation of the agreement in 2019, at a time when countering China’s regional ambitions is dominating Canberra and Washington’s agenda, a decline of trust and strategic coordination in Northeast Asia could still spell disaster.

Combined with China’s punitive economic measures against South Korea after its contentious deployment of THAAD air defence systems in 2016, let alone the enduring tensions with the North, Seoul faces a hostile climate in both the economic and security realms. For resources critical to South Korea’s booming tech sector and mammoth green energy ambitions, Australia offers a rational – if not singular — option for expanding cooperation.

In a perverse sense, South Korea’s turbulent diplomatic ties with its eastern neighbour have presented unique opportunities for Australia.

Developments in the region – such as Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Quad pact between the United States, India, Japan and Australia – may have also amplified a sense of strategic isolation in Seoul. After years of admirable but largely fruitless efforts by the Moon administration to mend ties with the North, Seoul has found itself on the back foot in the rapidly changing security and economic architecture of the wider region. An architecture in which, to Seoul’s possible concern, Japan is far better represented within.

Australia’s remarkably strong relationship with Japan has thus presented itself as a convenient backdoor for South Korea to expand its own efforts of regional economic integration. It was no coincidence that Moon’s visit to Canberra was accompanied by South Korea announcing its intention to join the CPTPP. After years of stern resistance from Tokyo, Australia’s concurrent support of Korea’s entry to the CPTPP – made clear during Morrison and Moon’s joint conference in Canberra – was invaluable as a symbolic stepping stone to overcome regional roadblocks.

In a perverse sense, South Korea’s turbulent diplomatic ties with its eastern neighbour have presented unique opportunities for Australia. South Korea’s ongoing trade difficulties with Japan has accelerated efforts in Seoul to develop relations with resource-rich democracies, including Australia. Canberra also finds itself in an unprecedented position, as its ties with South Korea as well as Japan continue to strengthen, to act as a harmonising presence in Northeast Asia’s delicate balance of power. In a speech made in 2019, Scott Morrison highlighted that the “Indo-Pacific would be even stronger if Japan and [South Korea] can overcome their recent tensions”. It may be time for Australia to see itself as having a possible role in aiding or facilitating this process.

While the focus in Austarlia almost reflexively turns to China, it is important to recognise the complex and simmering rivalries festering between the other two major economies in the region. South Korea’s efforts to enhance ties with Australia should not be seen so much as an affirmation of an assertive China policy but more as an effort to capitalise on Australia’s potential to act as both mediator and strategic ally in the wider region.