One of the ironies of the age is that as the United States’ prestige declines, its “virtual power,” its power to command attention, has never been greater. Last month, the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was not only global news but a matter of grave concern for people from Chile to Norway, many of whom probably couldn’t even name a member of their own country’s highest court. A tweet by Donald Trump is by definition an international incident.

We’re in a time when American politics is a global spectator sport, and a freshman member of Congress can be as famous as a rock star.

It is questionable, however, whether this fixation on the daily ups and downs of American partisan politics is really contributing to a better or more realistic understanding of America. Indeed, it may even be exacerbating the tyranny of the present and the fog of the Trump era, which may, after all, have only a few weeks to go.

Sometimes, in order to see something more clearly, it’s best to take a step back. In this case, 60 years back.

Voter suppression and claims of fraud also played a large part in the election of 1960.

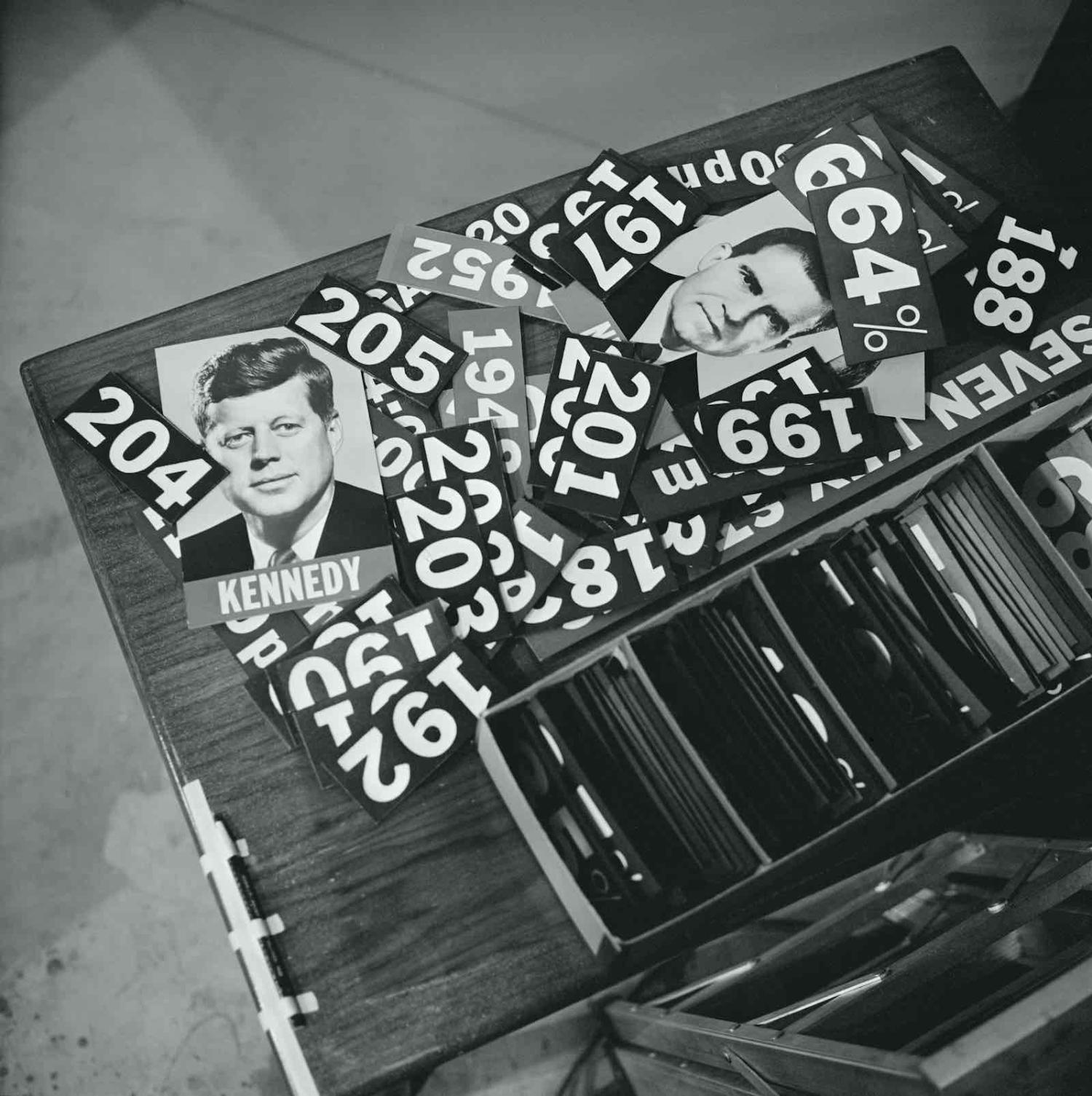

American historians often claim the 1960 presidential election marked the first modern election and set the pattern for every one since. An election that involved lying, the fusing of politics and entertainment, conspiracy theories, hyper-partisanship, threats to not accept election results and claims of voter suppression, voter fraud and foreign interference – sound familiar? A look back illuminates the grievances, real or imagined, that drive the behaviour of the modern Republican party.

The most prominent question in the 1960 campaign was the so-called “missile gap”. This was the simply false idea that during a Republican administration the Soviets had surpassed the US in intercontinental ballistic missile technology, and that “the deterrent ratio”, as the Democratic candidate John Kennedy put it one speech, had shifted unfavourably against the US. Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic candidate for President in 1952 and 1956 and a pillar of the American establishment whom Kennedy would appoint ambassador to the United Nations, went further, accusing Dwight Eisenhower, no less, of “unilateral disarmament at the expense of our national security”.

It is hard to imagine anything more irresponsible than, in a climate characterised by legitimate fear of a nuclear first strike and, often, anti-communist hysteria, claiming without proof that the US had fallen behind the Soviets in nuclear technology. The Democrats could claim that there were some in the US military, in particular the Air Force, who took this view, but there was never any solid intelligence to support it, and Kennedy had been fully briefed by the CIA, whose analysts correctly noted that the US was still well ahead of the Soviets in July 1960.

Meanwhile, on the other side, the Republican candidate, Richard Nixon, had done more than anyone else but Joe McCarthy himself to create the climate of hysteria the Democrats sought to exploit.

The role of the Soviets in the 1960 election was not limited to the missile gap or red-baiting. In his memoirs, Nikita Krushchev plausibly claimed that the Politburo decided not to release Gary Powers, the pilot whose U-2 spy plane had been shot down on 1 May 1960, in the hope of influencing a close election in favour of Kennedy, whom the Soviets believed, wrongly perhaps, would be better for their interests. Krushchev also claimed, less plausibly, that in an election that was so close the question of who actually won the popular vote is still disputed, this intervention may have made a decisive difference.

Then there is the “hijacking” of a political party by a relative outsider with celebrity appeal and a sordid private life, as it used to be called.

Before 1960, most primaries were non-binding preference votes and the candidate was determined by party bosses who picked their states’ convention delegates. The young and photogenic Kennedy, knowing that as a junior Senator he could never beat competitors like “the master of the Senate”, Lyndon Johnson, at their own game, mounted a new kind of campaign. Drawing on his immense wealth and with the co-operation of a media that then, as now, is obsessed with celebrity, Kennedy showcased his personal appeal by participating in primaries neglected by other candidates and created his own cadre of operatives throughout the country.

As for JFK’s private life, suffice it to say that it resembled that of Donald Trump more than any other previous president’s.

If partisan politics was in some ways worse in 1960, American society is much less unified today, as once “neutral” institutions have been politicised at the same time as respect for politics and the political class has collapsed.

Voter suppression and claims of fraud also played a large part in the election of 1960. Jim Crow laws were still in place throughout the South, preventing nearly all blacks and even many poor whites from voting in those states, most of which were still won by the Democrats. After the election, many Republicans including the departing President, Eisenhower, wanted Nixon to challenge the results in several states, in particular Illinois and Texas.

No one has ever been able to prove that fraud cost Nixon the election, and one reason he decided not to challenge may have been that he was worried that a thorough investigation would reveal Republicans had engaged in fraud themselves. But there is no doubt that fraud was routine in Chicago under “Boss Daley” – that is, Mayor Richard J. Daley – and in the Texas of Lyndon Johnson. In any case, the situation gave Nixon the opportunity to play the statesman, something he would rarely do again in a career that ended with him being the first president forced to resign.

None of which is to downplay the many problems America has today. If partisan politics was in some ways worse in 1960, particularly in terms of voter fraud and suppression, American society is much less unified today, as once “neutral” institutions have been politicised at the same time as respect for politics and the political class has collapsed. And then there is the elephant, Republican in this case, in this room.

Democrats’ complaints about voter suppression today have much more legitimacy than Republicans’ theories about voter fraud. Donald Trump is a combination of the personal and political vices of previous presidents, including Nixon and Kennedy, without any of the virtues. But the idea that in a two-party system, where each side reflects and reacts to the other, everything bad about the system is the fault of only one side beggars belief.