France’s Interior and Overseas Territories Minister Gérald Darmanin visited Noumea from 1 to 4 June to keep pressure on local parties to agree on New Caledonia’s political future, including by threatening unilateral action, and playing the China card. Some small progress was made, but divisions remain deep.

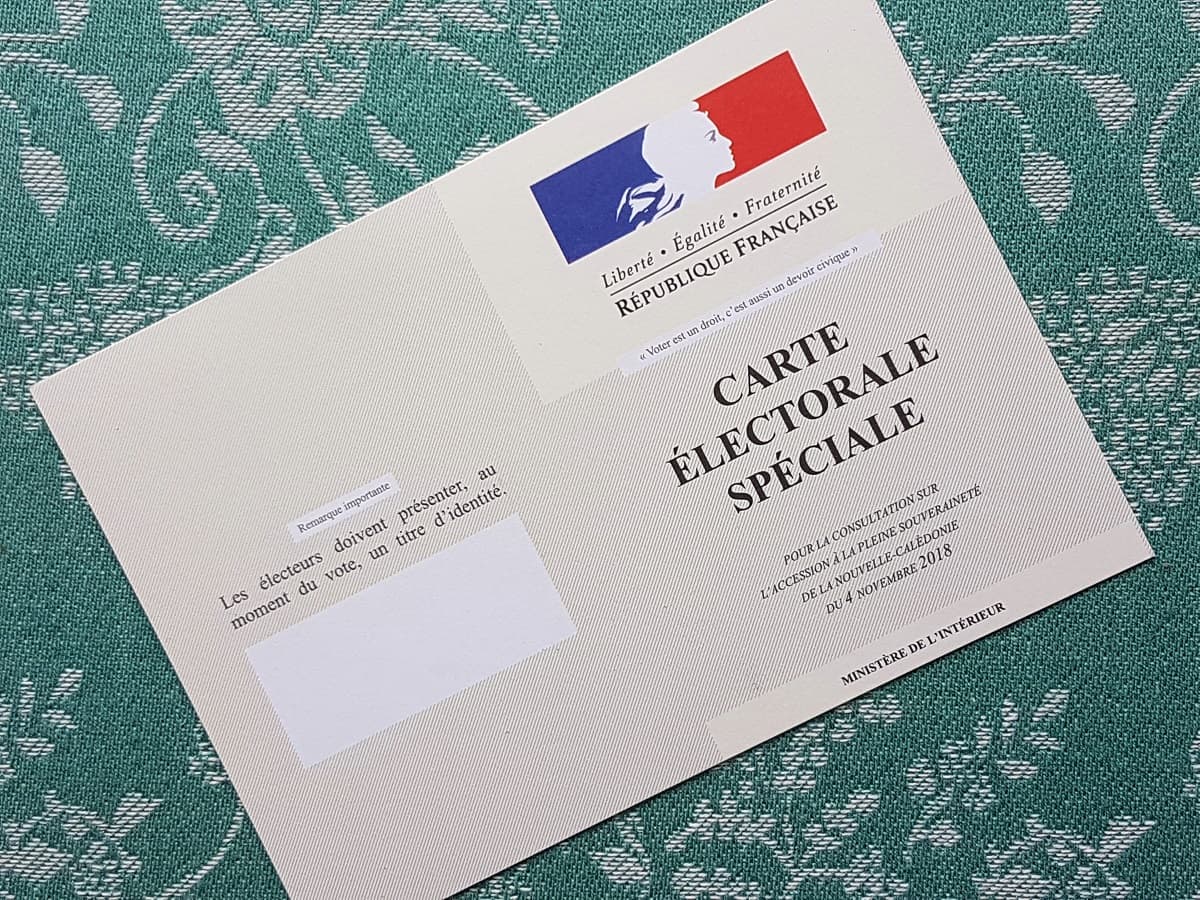

After the failed third referendum on independence in December 2021, which independence leaders describe as robbing them of their vote as the 1998 Nouméa Accord came to its end, the last 18 months have seen consistent efforts by France to oversee discussions about future governance in the territory.

France’s carrot-and-stick efforts have ranged from reminders about its economic largesse on which New Caledonia depends, to overt threats that if locals can’t agree, France will impose a solution. A stumbling block has been the rejection by Kanak independence leaders of the final vote, which they boycotted, accusing France of holding the ballot when their communities were being devastated by the Covid pandemic.

Kanak leaders at least attended talks in Paris in February and in Nouméa during Darmanin’s June visit. Yet while they participated in these bilateral discussions with the minister, they again declined trilateral talks with local loyalist parties.

To cajole some cooperation, Darmanin made three proposals. First, a promise of self-determination “within one or two generations”, a timeline rejected outright by independence leaders who said they do not want to wait another 50 years. Their main priority remains to work through the United Nations and the International Court of Justice for a self-determination vote, if necessary under international auspices.

Second, Darmanin said France did not rule out further transfers of core sovereign responsibilities it retains – foreign affairs, defence, currency, justice and public order – after decades of delegating numerous other responsibilities to local government.

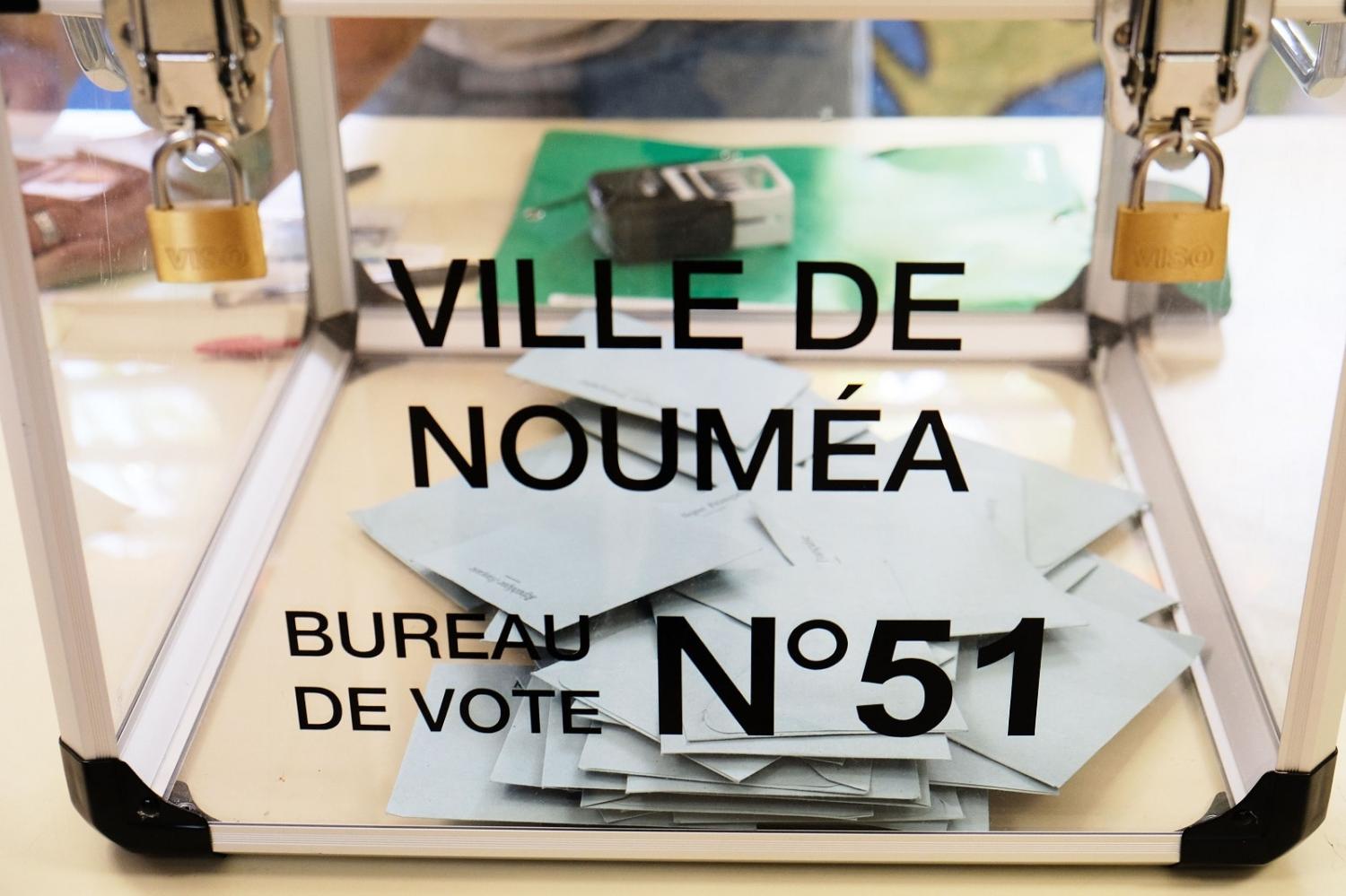

Finally, he addressed the most pressing point, that of restricted voter eligibility in local provincial elections (essentially confined to those resident in 1988 and their descendants ), next due in May 2024. As the Nouméa Accord ends, loyalists are clamouring to drop this provision, which favours indigenous Kanaks. Arguably, however, the elections and provincial assemblies themselves need to be renegotiated, as they too were created under the now-expired Accord. Voter eligibility is a fundamental area of difference between Kanaks and loyalists. Kanaks are afraid of being outnumbered in local elections by French residents, including transients such as metropolitan administrators and visiting experts, while loyalists claim the one person-one vote French Republic guarantee.

To encourage compromise, Darmanin proposed a possible residency requirement of seven years to the date of the vote. Loyalist leaders said this was too long, and proposed three years, while one independence leader guardedly responded they would want at least ten years, but only with further technical work. In a subsequent communiqué, the independence FLNKS (Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front) coalition elaborated, calling for France to undertake simulations to enable consideration of various options. The FLNKs only accepted opening the question of the restricted electorate within a broader political agreement about the future. They noted, for example, that they had already offered the French government options for self-determination and the further transfer of sovereign responsibilities.

Darmanin also released two major reviews: one, of the decolonisation process to date, a review long sought by independence leaders; the other, an implementation “audit” of the Nouméa Accord. While both were basically prepared by French experts (with a former Chair of the UN Committee on Decolonisation co-authoring one of them), an initial skimming of their contents indicates a genuine effort to acknowledge areas of achievement and identify areas of weakness. Loyalist and independence leaders will no doubt have their own views when they have the chance to absorb the detailed documents. FLNKS leaders have initially noted they were “perplexed” by some conclusions, but would consider the content and form of the reviews.

The papers are a reminder of the extraordinary and innovative achievements and compromises of the Nouméa and predecessor Accords ending the 1980s civil disturbances over independence. They will form a basis for discussion at least.

Unfortunately, the June talks show how far apart the parties remain. In a televised interview after the talks, Darmanin asserted all three referendums meant New Caledonia remained in France. He underlined France’s need to define New Caledonia’s place within the “national union” under President Emmanuel Macron’s Indo-Pacific vision, especially given the “predatory behaviour” of China. He reiterated that if local parties could not make progress in discussions, then France would.

Australia has been a long-time silent supporter of New Caledonia’s peace agreements. Australia’s security interests favour stable, democratic governance within the Western alliance for this archipelago, known during the Second World War as a strategic “battleship” off the east coast. But this consideration should not overshadow – indeed it should underpin – the need to articulate Australia’s expectation that France will fulfil the spirit and letter of commitments it has made to all local parties, as those agreements end.