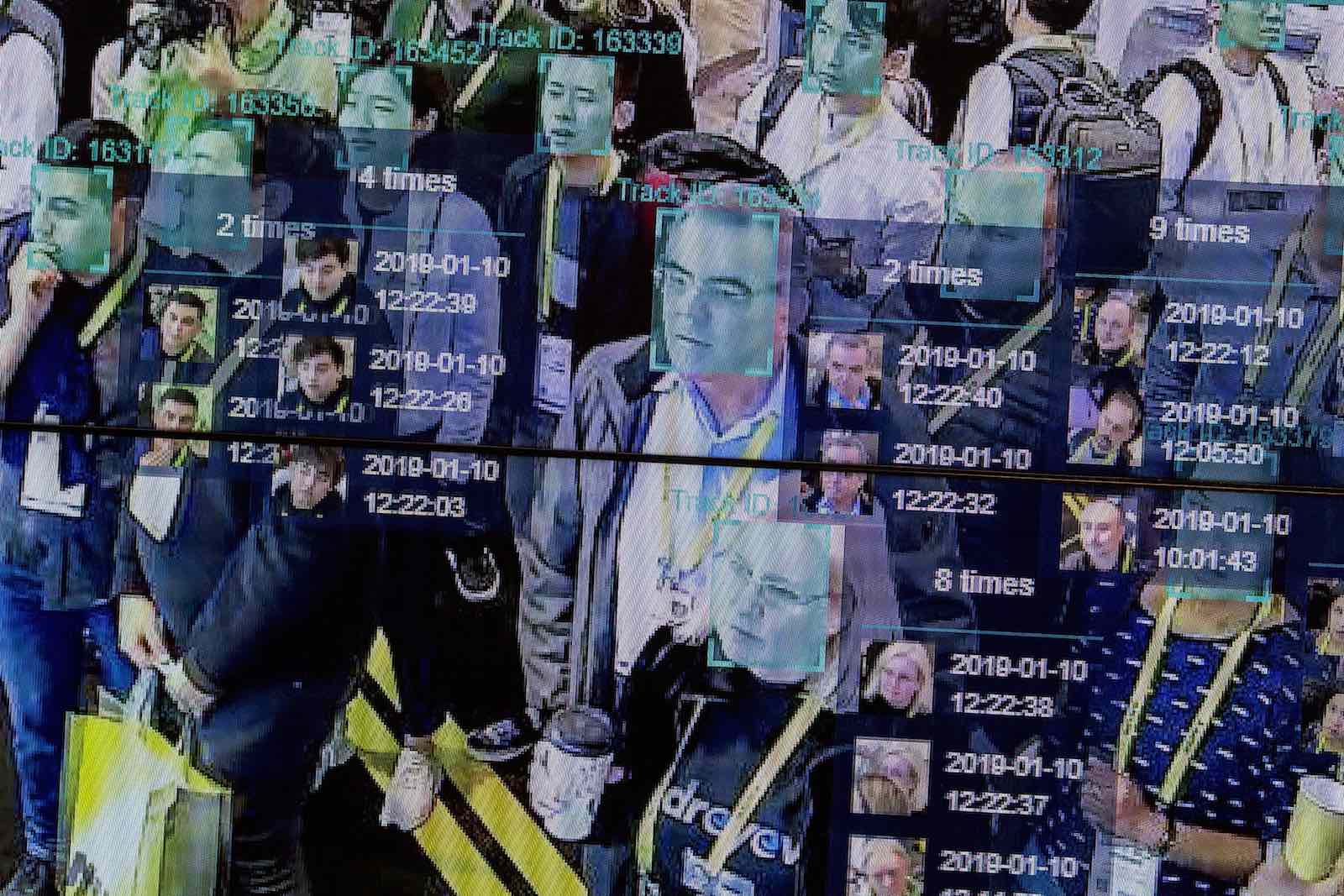

Just like the enigmatic algorithms behind popular social media platforms, facial recognition algorithms are unleashing their own share of social problems. Machine-learning systems, the bedrock of artificial intelligence, or AI, use data to learn who you are, where you go, what you do, and what people like you do. Recent advances in machine learning have spawned important increases in AI-driven facial recognition technology, supercharging CCTV systems to become agents of surveillance in new and sometimes troubling ways.

These advances have made facial recognition an indispensable tool for many, ranging from Taylor Swift to your friendly local casino boss. The Covid-19 pandemic has added fuel to the fire by sparking an “arms race” among companies vying to develop “mask-proof” facial recognition systems.

But the technology raises important issues of governance, justice and fairness. In recent months, the Black Lives Matter movement has taken action to address what it sees as an abuse of police power and surveillance technology. Facing reputational and financial costs, several major tech companies stopped developing facial recognition or selling it to the police. Microsoft went as far as petitioning the US Congress to legislate against it.

Tech giants rarely advocate for industry regulations. Although they may have complex motives, companies such as Microsoft speaking out against this AI-powered, fast-growing technology in part reveals the unusually disruptive power of facial recognition technology and its unruly place in the landscape of AI governance.

The implications for justice and fairness are particularly striking because of the way facial recognition can embed existing discriminations and bias. Facial recognition algorithms need data to train their decision-making processes. They are at present trained on image datasets often dominated by the demographic majority (e.g., light-skinned individuals, in the case of Australia and the United States). This means they are smart, but not smart enough.

Researchers have found that racial minorities are 10 to 100 times more likely to be falsely identified — they simply don’t show up often enough in the dataset to train the algorithm correctly. And because benchmark datasets (those datasets used to evaluate the performance of algorithms) were similarly biased, the inaccuracies of these tools remained undetected until dark-skinned people were wrongly accused of crimes they did not commit.

This is where AI governance comes in.

AI governance is a growing field among technologists, social scientists and policy scholars working on mitigating the societal and global risks of AI. Researchers in AI governance seek to make the development of AI more accountable and transparent. The research and auditing tools developed by these researchers were instrumental in exposing the rampant biases in facial recognition software on the market and pressuring tech giants to give them up.

But the danger of facial recognition goes beyond inaccuracy and bias. Even when it works accurately, the technology is easily weaponised against already vulnerable groups. US law enforcement is known to use facial recognition to track down and arrest protesters. China’s facial recognition technology has essentially automated racial profiling to keep tabs on the country’s 11 million Uighurs. Examples of potential abuse go beyond governments: a facial recognition app developed by the Russian company NTechLab provides the perfect tool for stalkers and sexual predators.

Unfortunately, despite the tech giants’ cooperation, the biggest players in facial recognition are in fact small, specialised companies that continue to forge ahead for the next frontier in facial recognition, their pursuit of commercial opportunities undeterred by ethical concerns.

One of the most controversial of such companies, Clearview AI, supplied its software to Gulf countries with documented human rights abuses and recently signed a contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) — the US border agency known to forcibly separate children from parents trying to enter the country.

This is where the “second wave” of AI governance should kick in, as law professor Frank Pasquale has carefully explained. While the “first wave” of AI governance sought to improve inclusivity and accuracy in algorithmic systems, the second wave “asked whether they should be used at all — and, if so, who gets to govern them”.

Regulators are slowly waking up to the technology’s deep intrusion on civil liberty, privacy and free speech.

However, no national-level regulations exist today that govern the development and use of facial recognition. Even the world’s most robust privacy law — Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) — failed to stop politicians from letting the technology scan faces without explicit consent, so long as it serves “public security”. The Australian Federal Police and the police of several states are registered users of Clearview AI, and Australian legal protection against biometric surveillance barely exists.

The Australian CEO of Clearview AI reportedly said that in the US context, it is his First Amendment right to harvest billions of social media images, because those internet images are “publicly searchable”. It did not appear to concern him that these facial IDs in his database are then accessible by the police and any of his private clients. Indeed, under the current global legal landscape, we might be left to fend for our own faces in the Wild West of the Web.

Thanks to activists’ years of petitioning and watershed movements such as Black Lives Matter, some regulators are slowly waking up to the technology’s deep intrusion on civil liberty, privacy and free speech.

A national-level bill was recently introduced in the US in response to mounting public pressure, but it lacks teeth and is expected to stall in the Republican-majority Senate. However, local-level bans on facial recognition are mushrooming across the country. The European Commission recently started planning new legislation that goes beyond the GDPR to give Europeans explicit rights over their own biometric data. If successful, this would become the first comprehensive regulation on facial recognition explicitly hatched under the tenet of ethical AI governance.

One can only hope this kind of regulation will catch on globally soon, before facial recognition creeps into random daily objects and our next “smart TV” starts scanning our faces.