The verdict of John le Carré (real name David Cornwall) on the outcome of the Cold War was: “The right side lost, but the wrong side won”.

This ambiguous conclusion is attributed to le Carré’s favourite character, George Smiley, in his novel The Secret Pilgrim, but it is an unmistakable theme of most of le Carré’s post-Cold War novels. Le Carré’s death this week came after decades of disillusionment with the new world order and his increasing disenchantment with the behaviour of the Cold War’s victors.

Not that le Carré was rooting for the Soviet bloc – “the right side lost”, after all – but he became convinced that the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the associated demise of anti-communism, left the West without a coherent ideology.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was predicted to spell the end of the spy novel. Le Carré, however, welcomed plotting on a broader canvas.

The vacuum was filled, according to le Carré, by opportunistic politicians, rampant capitalism, nationalism, isolationism, rapacious multinational corporations, international criminal organisations and a Russian kleptocracy. Above all, le Carré showed in his later novels an increasing disillusionment with the United States as the acknowledged leader of the victors.

The ideals that had driven the West in the war against communism came to be forgotten, according to le Carré. Those ideals are a central concern of his early novels. In a 2017 interview, he defined these ideals as “a notion of individual freedom, of inclusiveness, of tolerance. All of that we called anti-communism”.

Le Carré’s characters continually agonised over the lengths to which liberal democracies should go, or must go, in order to defend these ideals. This tension – whether the ends justified the means – is most obvious in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, his third novel, and the one which launched his career as a full-time writer.

Le Carré’s world of espionage is never black and white but is a world shaded in grey. Communism may have been the cause of the Cold War, but not all the soldiers are evil: “half-angels fighting half-devils” in the words of one of his characters.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was predicted to spell the end of the spy novel. Le Carré, however, welcomed plotting on a broader canvas. He responded to the age of globalism. His novels now explored Middle East politics, the war on terror, the international pharmaceutical industry, the world of arms dealing, the financing of terrorism, Brexit and the Russian mafia. Many of these novels were poorly received by reviewers, the reviews often reflecting the reluctance of critics (and fans) to accept the new world order.

Le Carré was a virulent critic of America’s reaction to the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001 and the support given by the Blair government in the UK. He published an essay “The United States Has Gone Mad” just before the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, and his anger spilled over into his next novel, Absolute Friends.

His former publishing editor, Robert Gottlieb, a one-time editor of The New Yorker, believes le Carré’s books “grew more and more virulently anti-American”. Gottlieb’s judgment may have been coloured by le Carré suddenly dumping his long-time publisher in favour of Viking, but there is truth in Gottlieb’s assessment.

Gottlieb was writing before the election of Donald Trump, which was for le Carré the last straw. His final novel, An Agent Running in the Field, includes a savage denunciation of Trump’s foreign policy and some very personal swipes at Vladimir Putin.

This book and le Carré’s penultimate novel, A Legacy of Spies, show he was just as profoundly disillusioned by his own country, particularly by the vote on Brexit and the blow this struck against European integration, a cause he strongly supported. Last year he wrote: “I think my own ties to England were hugely loosened over the last few years. And it’s a kind of liberation, if a sad kind.”

Le Carré’s disillusionment was not confined to the international order he explored as a writer. He resented being confined as a genre novelist. He confessed this resentment – even admitting to “over time a kind of impotent anger” – in a foreword to a 50th anniversary edition of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

He wrote: “From the day my novel was published I realised that now and forever more I was to be branded as the spy turned writer rather than as a writer who, like scores of his kind, had done a stint in the secret world and written about it.”

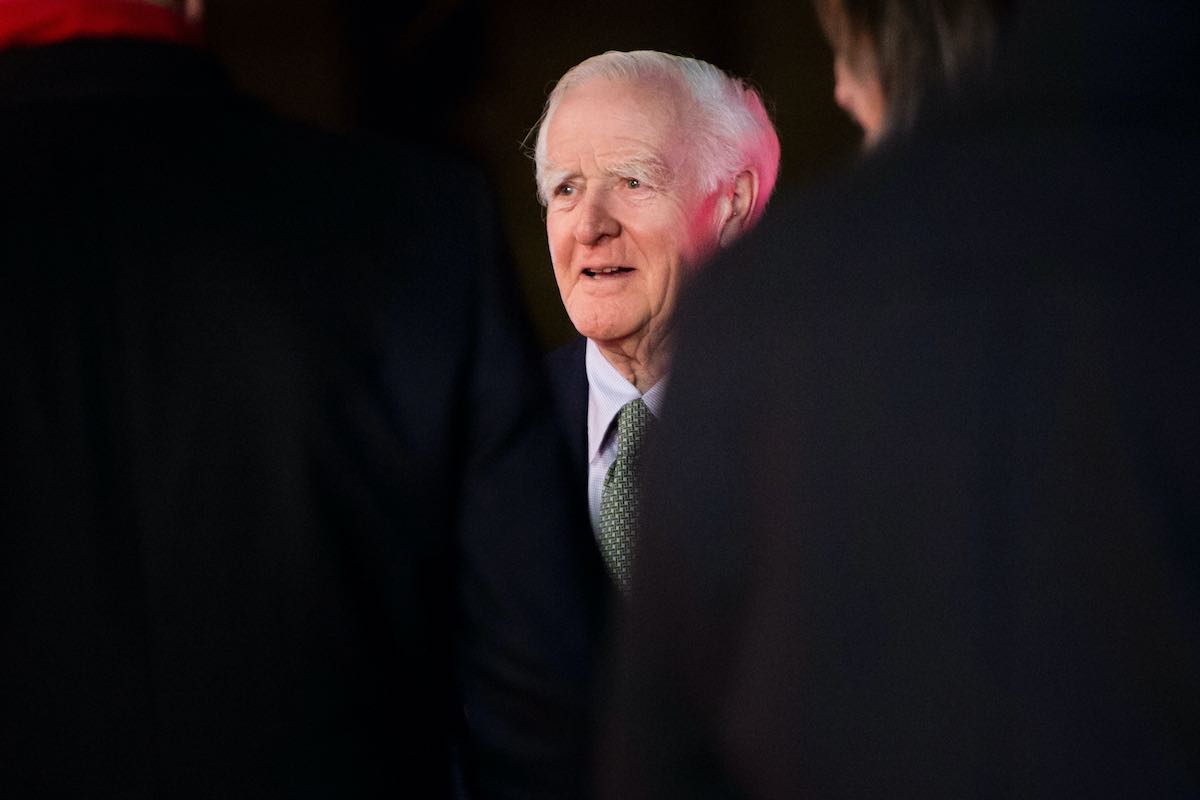

Main image via Flickr user Adrian Scottow