Australia and the anti-trafficking regime in Southeast Asia

This working paper reviews recent trends in human trafficking in Southeast Asia and the status of the anti-trafficking regime in ASEAN member states. It examines the role of Australian governments in helping establish and develop anti‑trafficking legislation and national referral mechanisms in ASEAN states and argues more can be done for victim protection. Photo: Getty Images/Jonas Gratzer

Introduction

Successive Australian governments have invested heavily in efforts to combat people smuggling and human trafficking in Southeast Asia. In 2002, Australia helped establish the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime, which it co-chairs with Indonesia.[1] Since its inception, progress has been made in efforts to establish a stronger anti-trafficking regime in the region. For example, nine of the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have strengthened their respective national anti-trafficking legislation. However, much work remains to be done.

At the Sixth Bali Process Ministerial Conference on 23 March 2016, the Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi criticised the Process for its failure to address the Andaman Sea refugee crisis in 2015, sparked by the forced migration of thousands of Rohingyas fleeing Myanmar and Bangladesh.[2] When it was established in 2002, the Bali Process was a regional response to irregular migration, and was not intended to deal with forced migration of refugees. Nevertheless, Marsudi’s comments underline the need for regional efforts to tackle people smuggling and human trafficking to keep pace with the evolving situation in the region.

The aim of this working paper is to assess the progress that has been made in establishing a stronger regime for tackling human trafficking in Southeast Asia and to highlight gaps in these efforts that might provide a focus for Australian assistance in the future. The paper begins with a brief overview of current trafficking trends in the region. It then assesses anti-trafficking legislation in force in all ASEAN member states. The final section of the paper identifies areas where Australia can help to further strengthen the anti-trafficking regime in the region.

Current trends in human trafficking in Southeast Asia

To understand the current situation in Southeast Asia with respect to people smuggling and human trafficking, it is important to be clear about the distinction between the two. People smuggling is the act of moving people across borders into countries for which they have no authorised travel documents in order to obtain a financial benefit.[3] Huuman trafficking is the act of moving people either internally or across borders through coercion or deception for the purpose of exploitation in the destination country.[4] In the case of people smuggling, people are generally being moved voluntarily. In practice, however, the line between people smuggling and human trafficking is often blurred, especially in Southeast Asia.

In terms of border protection, the Australian Government has largely focused on refugee and migrant smuggling, more than on human trafficking. Specifically, the stress has been on irregular arrivals by sea from the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia. The focus has also been on the people smuggling networks in Southeast Asia that help facilitate these irregular movements to Australia. Human traffickers often share the same networks as people smugglers. Most irregular migrants from Afghanistan and Iran who have arrived in Australia in recent years have come via countries in Southeast Asia. In some cases, they have reached countries in Southeast Asia legally and are then smuggled (or sometimes trafficked) for the onward journey to Australia.

While human trafficking in Southeast Asia has relatively little impact on Australia directly, Australia has an interest in combating it, not least because it is linked to people smuggling. This was highlighted by the 2015 Rohingya crisis, where smuggled refugees and migrants from Myanmar and Bangladesh were abandoned in the Strait of Malacca and the Andaman Sea after a crackdown on human traffickers following the discovery of mass graves in jungle camps in Thailand. The main destination countries of the smuggled Rohingya refugees were Malaysia and Indonesia, as they are Muslim majority countries, with some intending to reach Australia.[5]

Since human trafficking and people smuggling are closely interrelated, the so-called ‘push-down and pop-up’ effects of human trafficking have direct implications for migrant smuggling.[6] When human traffickers or smugglers are pushed down by tough regulations and a strong stance on enforcement in one state, they move to another that has less rigorous controls. This is evident in many trafficking cases. If traffickers cannot move victims within Southeast Asia, they target neighbouring countries, including much richer or bigger countries such as Australia.

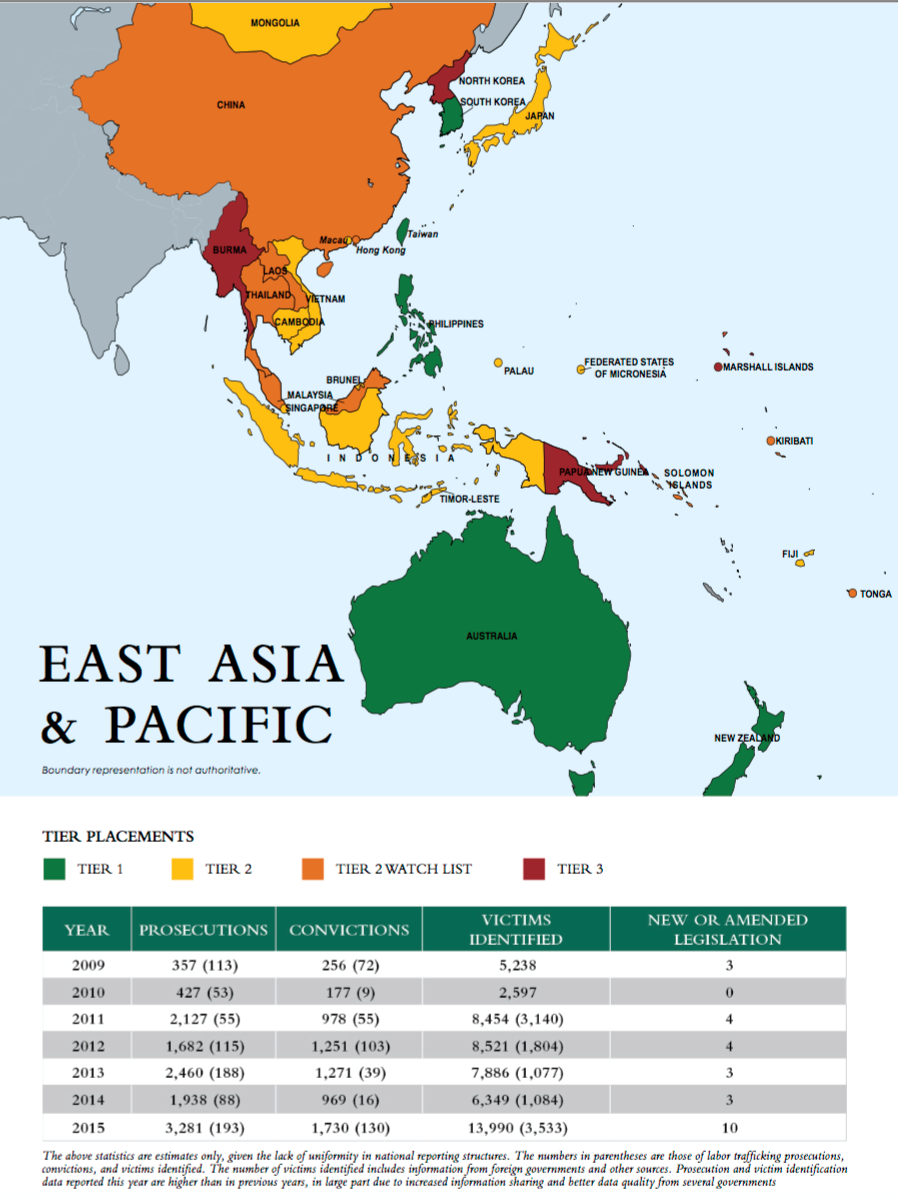

Human trafficking is a significant problem in Southeast Asia. The 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report, published annually by the US State Department, places Myanmar in its lowest tier ranking in terms of a country’s policy response to people trafficking (Tier 3), and Thailand and Malaysia in the second-lowest ranking of Tier 2 Watch List.[7] But as the map below shows, no country in Southeast Asia has a particularly good record of tackling human trafficking.

Map of Southeast Asia on combating trafficking in persons

Source: US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report: July 2016, 58

Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, and the Philippines are the main source countries for human trafficking. Myanmar, in particular, has become a significant source country because of its geographic location and porous borders. It shares borders with Bangladesh and India in South Asia, China in Northeast Asia, and Laos and Thailand in Southeast Asia. Many of the country’s ethnic minorities (Karen, Rakhine, Kachin, Mon, Shan, and Karenni) live along its borders, and it is from here that many trafficking cases originate. Shan women and girls are often trafficked north into China, while Karen and Mon women are trafficked south and east into Thailand.[8]

The main causes of human trafficking in Southeast Asia are poverty, lack of employment opportunities, economic underdevelopment, poor education, and a lack of the rule of law in source countries. However, the causes have also become more diverse and complex. Armed conflicts, religious persecution, and racial discrimination, which were once seen as the causes of forced migration, have become key drivers of human trafficking. In addition, high levels of corruption among government officials and a lack of police training has facilitated trafficking.[9]

Labour trafficking targeting young persons from less developed countries is a particular problem in Southeast Asia. According to International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates, the Asia-Pacific region accounts for the largest number of forced labourers in the world (11.7 million people), more than half of the global total.[10] Males and females of all ages are being exploited as modern-day slaves, especially in low-skilled sectors such as domestic work, construction, and the seafood industry. Government officials are often complicit in labour trafficking for infrastructure projects and state-run agricultural and commercial ventures.[11] Of particular concern are orphans and children from poor families, some of whom are deceived or intimidated into recruitment especially in the agricultural and services sectors. For example, an estimated 28 000 children work as domestic workers in Phnom Penh alone.[12]

The use of forced labour is particularly prevalent in the seafood industry in Southeast Asia.[13] Among 7000 trafficked persons assisted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2015, in East and Southeast Asia, 88.4 per cent were trafficked for forced labour (excluding domestic work).[14] Labourers from Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos working in the international fishing industry have been subjected to debt bondage, passport confiscation, or false employment offers, with some being physically abused and forced into detention for years aboard vessels in international waters.[15] Trafficked fishermen are particularly vulnerable as they often have no access to emergency helplines or social services at sea. There have been reports of Cambodians in Thailand without documentation being locked up in containers and trafficked onto fishing boats.[16] On shore, vulnerable populations, including children, have been trafficked to seafood processing factories and are often unpaid or significantly underpaid. They are also exposed to physical and mental violence from employers. Those employing trafficked labour in Southeast Asia are in a number of cases part of supply chains of large and well-known multinational companies.[17]

Sex trafficking within Southeast Asia often receives the most attention from the media. The exact number of trafficked persons for sexual exploitation is unknown and estimated figures vary greatly from one organisation to another. The Global Slavery Index estimates 30 million persons were trafficked in the Asia-Pacific region in 2015. Among them, 2.63 million were from the ASEAN countries.[18] Young women and girls are most commonly trafficked, but boys are also trafficked as part of prostitution rings.[19] Virtual trafficking is an emerging crime that involves child pornography and the exploitation of children in Southeast Asia, especially in Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines.[20] Some commercially arranged fraudulent marriages of women from the region in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea have also been found to be, in practice, labour and sex trafficking.[21]

The anti-trafficking regime in Southeast Asia

To combat human trafficking in Southeast Asia, Australia has encouraged ASEAN countries to sign and ratify the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, as a supplement to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Palermo Protocol).[22] The Australia Government has also provided Southeast Asian countries with legal training on drafting anti-trafficking legislation for the past decade.[23] Australian lawyer and leading global expert on the international law on human trafficking Dr Anne Gallagher has played a pivotal role in this program.[24]

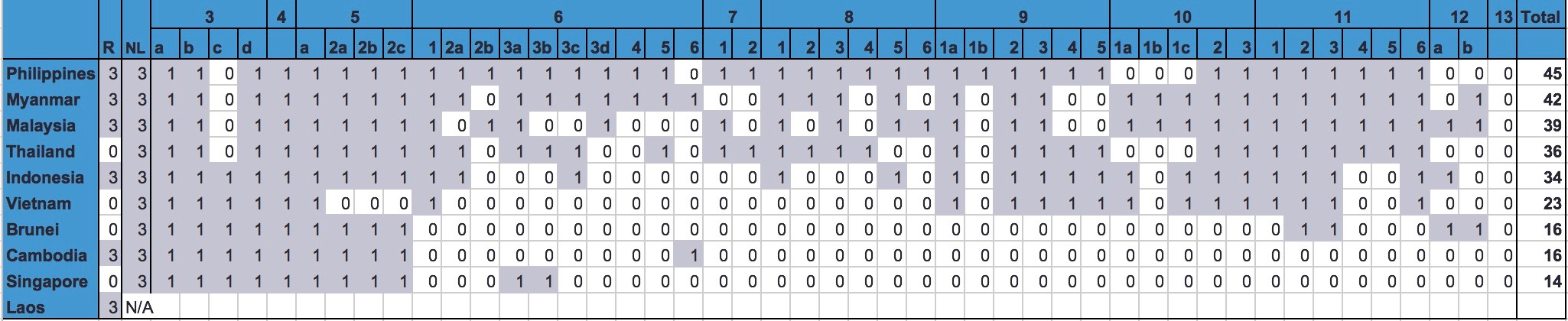

Table 1 is an index of the ASEAN states and their ratification status and legal compliance with the Palermo Protocol, as at April 2016. The analysis is based on data collected from national legislation, survey documents, and victim/criminal records from all ten ASEAN countries. The data was collected as part of two research projects conducted with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the IOM Regional Offices in Bangkok in 2014 and 2015 and supervised by the author.[25]

Countries are allocated three points if they have ratified the Palermo Protocol (‘R’) or if they have separate national legislation (‘NL’) for tackling human trafficking. Countries are also given one point for legislative compliance with each article of the Protocol. The ratification status is an important indicator of the state’s commitment to international cooperation, while a separate national legislation score indicates the first legal step to realising the commitment. The rationale for allocating three points to a country’s ratification of the Protocol or for the creation of national legislation is that they imply a greater legal and political commitment to fighting human trafficking than complying with individual articles.

Table1: ASEAN legal compliance with the Palermo Protocol

Source: Author’s updated analysis from the two surveys in footnote 25, as at June 2016

It is also important to note that the ratification of the Palermo Protocol and enactment of national legislation are only the first steps in a country’s development of an effective anti-trafficking regime. Other important steps would include actual implementation and enforcement of the legislation, prosecution, and remedies for trafficked victims.

Since the inception of the Bali Process, nine of the ten ASEAN member countries have either enacted or amended their national legislation to reflect the international standards on combating human trafficking prescribed in the Palermo Protocol. The one exception is Laos, which does not have separate legislation on anti-trafficking as at June 2016, although trafficking is an offence under its penal code. This is a significant achievement for Australia’s regional efforts to build a stronger anti-trafficking regime in the region.

With the exception of Laos, all ASEAN countries are generally in legal compliance with Articles 3, 4, and 5 of the Palermo Protocol, which define human trafficking as a criminal offence. Myanmar does not have a separate clause implementing Article 3c of the Protocol, which states: “[t]he recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation shall be considered ‘trafficking in persons’ even if this does not involve any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article.” Vietnam does not provide a clear definition of human trafficking as a criminal offence in its 2012 Law on Prevention and Suppression against Human Trafficking (LPSAHT).[26] Instead, the LPSAHT refers to Articles 119 and 120 of Vietnam’s penal code, which deal with the prosecution of human trafficking offences.

Articles 6–8 of the Palermo Protocol relate to the protection of trafficking victims. All ASEAN countries have at least some protection clauses in their respective legislation. However, Brunei, Cambodia, Singapore, and Vietnam have poor protection regimes. With only limited implementation of Article 6, which details specific obligations for the “physical, psychological and social recovery of victims of trafficking”, more work needs to be done in ASEAN countries to provide support for those who fall prey to human traffickers.[27]

Articles 9–13 of the Palermo Protocol deal with the prevention of human trafficking and the promotion of regional cooperation and other measures to combat the practice. Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and the Philippines score highly here, whereas Singapore, notably, scores very poorly.

Overall, the Philippines (45 points) tops the ASEAN legal compliance with the Palermo Protocol index, followed by Myanmar (42), Malaysia (39), Thailand (36), and Indonesia (34). There is some discrepancy between these rankings and the rankings of ASEAN countries in the June 2016 US trafficking in persons (TIP) report. Specifically, in the US TIP report Indonesia has a higher tier ranking than Malaysia and Myanmar. One reason for this discrepancy is that Table 1 only focuses on the implementation of legislation, whereas the US TIP report also looks at the actual implementation of anti-trafficking regimes, criminal penalties against traffickers, and proactive victim identification measures as well as partnerships with non-governmental organisations (NGOs).[28]

Table 2 analyses the nature of the national anti-trafficking legislation that ASEAN countries have in place in a more comprehensive manner. It examines the following five criteria: (1) how each state defines trafficking; (2) the sentences imposed on convicted traffickers in national legal frameworks including anti-trafficking legislation and penal codes; (3) the number of bilateral treaties each state has to extradite criminals and return victims; (4) the status of national action plans (NAPs); and (5) whether states have national referral mechanisms (NRMs) that identify victims of human trafficking and refer them to the appropriate authorities and social services.

Table 2 (linked): Anti-trafficking regime among ASEAN countries

Source: Author’s compilation, as at April 2016

One of the significant gaps in the anti-trafficking regime that is highlighted in Table 2 is the general lack of NRMs in Southeast Asia. Only four of the ten ASEAN states have NRMs. Of all the anti-trafficking measures, NRMs are the most victim-centric, focusing on the rights of victims of human trafficking and ensuring they have access to justice and social services. The IOM has been encouraging countries to establish their own NPAs, which would promote a whole-of-government mechanism to protect victims of human trafficking.[29]

NRMs are also crucial to efforts to combat trafficking. Often the best way to identify those engaged in human trafficking is through reports from victims to community outreach programs.[30] This is very challenging in the regional context as most victims of trafficking are unaware of their rights and protections under local laws. During police raids, victims are often treated as complicit in the trafficking activity and typically face rapid deportation. For this reason, victims are hesitant to report trafficking and to seek help from service providers.

Having NAPs or NRMs in place, however, is not sufficient to fully protect victims of human trafficking unless underlying laws are comprehensive enough to cover all types of victims. For example, Myanmar has launched its second NAP for 2012–16 but its legislation does not include male victims. This is also true of Cambodia and Laos, where men are particularly targeted for trafficking in the fishing industry. This means, for example, that male victims are not provided with shelters to escape from their abusers. Additionally, although the IOM has devised indicators to help identify trafficking victims, ASEAN countries do not use the checklist. Victim identification is not systematic and it is often left to NGOs to carry out investigations. This puts pressure on NGOs, which are typically constrained by access to funding.

Generally, the implementation of newly enacted legislation and NAPs in Southeast Asia has been slow. There are a number of reasons for this including the lack of institutional capacity among regional countries, asymmetric economic development, and low levels of democracy and a lack of transparency and the rule of law.

First, a particular challenge in building institutional capacity is that governments do not systematically collect data on human trafficking. According to a review of ASEAN countries’ data collection on human trafficking in 2014–15,[31] much of the data involving victims of trafficking is not systematically or regularly collected. The data that is collected is often not accurate or up to date. The absence of a national or regional database on human trafficking makes it difficult to design policies to tackle human trafficking. This is one area Australia can help with more through training local researchers. As Anne Gallagher has noted, the lack of accurate data has prevented Laos from identifying gaps in its legal structure for drafting anti-trafficking law.[32] In order to draft new legislation, law-making processes must be based on an accurate understanding of the scale of the problem and on the profiles of victims and traffickers.

Second, the region’s asymmetric economic development is and will continue to be a driving force behind the need for trafficked labour. Rapid growth in some countries has led to growing demand for unskilled labour, and with it constant flows of migrants and trafficked labour from less developed to more developed countries in the region. For example, from Cambodia to Thailand, from Myanmar to Malaysia, and from Indonesia to Singapore. Relative wealth and the opportunity to send remittances home continue to be enticements that traffickers can use to coerce potential victims from poor villages into forced labour.

Third, the region’s low level of democracy and poor human rights record makes the implementation of new legislation focusing on victim protection highly challenging on the ground. This has an impact on the rights available to victims of trafficking who often need legal protection within host countries. For example, the government of Myanmar denies citizenship to an estimated one million men, women and children from a particular ethnic group, increasing their vulnerability to trafficking.[33] Under the military regime in Thailand, more attention is focused on the prosecution of traffickers than the protection of their victims. In Cambodia, under the highly corrupt Hun Sen regime, little is allocated for access to justice and social services for victims of human trafficking.

Australia and the anti-trafficking regime in Southeast Asia

Australia has taken a whole-of-government approach to the issue of human trafficking in Asia. Both the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Attorney General’s Department (AG) have been engaged in capacity-building efforts in Southeast Asia. In 2016 Australia announced an International Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking and Slavery.[34] The Interdepartmental Committee on Human Trafficking and Slavery, comprised of the Ministers for Justice, Foreign Affairs, Social Services, Women and Immigration and Border Protection, also reports annually on strategies to combat human trafficking and slavery.[35]

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) undertakes capacity-building activities and provides technical assistance to a number of countries to support efforts to address all forms of irregular migration, with particular focus on human trafficking and slavery. Specialist immigration officers, who focus on human trafficking issues and aim to prevent trafficking in source countries, are posted in Thailand, China, the Republic of Korea, and the Philippines. DIBP also continues to build relevant capacity through activities including border assessments, alert systems design and implementation, and development of border management systems including biometric capabilities, passport systems, identity verification, legal and regulatory frameworks, and protection frameworks.[36]

One of Australia’s main regional efforts to combat human trafficking is the Australia-Asia Program to Combat Trafficking in Persons (AAPTIP). The program started in August 2013, with a five-year commitment of A$50 million to strengthen the capacity of governments in the region to address human trafficking through criminal justice responses.[37] Partner countries for AAPTIP are mainly the sending countries, that is Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines, not the receiving countries where victims need to receive immediate and urgent protection. The stated objectives of the partnership are: to improve law enforcement agencies’ effective and ethical investigation of human trafficking cases; to train prosecutors, judges and court officials on effective and ethical prosecution of human trafficking as well as the fair and timely adjudication of cases; and to enhance regional cooperation and leadership on the criminal justice response to human trafficking in the ASEAN region. Australia also has a range of bilateral agreements on human trafficking with Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand, as at June 2015.

Given some of the gaps in the regional anti-trafficking regime identified in the previous section, there are a number of areas where Australian support for anti-trafficking efforts could focus in coming years. One area is the protection of victims. To date Australia’s focus has largely been on the first two Ps of the Palermo Protocol — prevention and prosecution. More work could be done on the third P — protection.

As noted above, regional governments have made slow progress on the protection of trafficking victims. While prevention and prosecution are important, what most victims want is a safe return to their home communities and to find sustainable and safe employment there.[38] Protection is also important to the success of any anti-trafficking regime. Without greater efforts on the sustainability of return, the risk is that returnees may once again become victims of trafficking and retrafficking.

Greater support for victims is particularly important when it comes to the trafficking of children. Any support also needs to be tailored to their particular needs. Simply sending children back to school is often insufficient. In one study in 2008, Save the Children found that only 25 per cent of school-age trafficked children wanted to go back to education after they were returned.[39] Most preferred to find work and this increases the likelihood that a returned child will be retrafficked. Recent findings from the Australian Institute of Criminology support this argument for Indonesian victims of human trafficking.[40] NGOs in remote villages in Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia have sought to address this problem by providing basic education focusing on numeracy and literacy, combined with practical training such as providing the children with computer and communication skills. In this regard, the UK Department of Education and the US Agency for International Development have been offering education to trafficked children.[41]

In some ASEAN countries, the lack of provision for victim protection reflects broader capacity questions, but not in every case. Singapore, for example, has been slow on the prosecution of traffickers and exploitative employers, as well as on the protection of foreign victims. Singapore only enacted its anti-trafficking legislation in 2014 and still has no NRM in place. Singapore’s lack of victim identification and victim protection is symptomatic of its reactive anti-trafficking mechanism.

To date relatively little of AAPTIP’s A$50 million budget seems to have been allocated to supporting victim identification and protection. However, there have been some positive developments over the past year. In November 2015, AAPTIP, in collaboration with the ILO, the IOM and the UN Action for Collaboration against Trafficking in Persons (UN-ACT), supported an ASEAN regional workshop on developing common indicators for victim identification. This work was endorsed at the ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crime in March 2016.[42] Activities relating to victim protection include providing victims of trafficking with details of support agencies and information about their rights within the criminal justice sector. Overall, AAPTIP as well as the Bali Process have focused mainly on capacity building and strengthening the criminal justice systems. In order to strengthen NRMs, AAPTIP should further encourage states to come up with more participatory victim identification, rescue, and investigation processes, as well as reintegration programs.

Before AAPTIP was launched in 2013, a Project Design Document released in June 2012 stated that research would be undertaken “to better understand what mechanisms are in place for the management of and support to victim-witnesses” in the criminal justice system. The report also warranted strengthening victim-witness support services and piloting new models based on structured multi-agency memorandum of understanding between justice and victim support agencies, partnership agreements with the government social welfare authorities, or embedding a victim-witness coordinator within a justice agency.[43] How much has been achieved is not yet clear. A midterm review of AAPTIP was due to be published in mid-September and as at the end of September 2016 was not yet available.

The Bali Process and the AAPTIP almost entirely work with state institutions. Within these two mechanisms, only a few programs have directly supported community outreach or engaged with local or regional companies. There are, however, some positive developments in recent years. Apart from the regional efforts, Australia, through the DFAT’s NGO Cooperation Program, has supported World Vision and Save the Children in Myanmar to provide outreach and support services to victims in the Mandalay and Yangon regions. The Bali Process has also started recognising the role of businesses in this area. The March 2016 Co-Chairs statement acknowledged the private sector’s role in preventing and detecting trafficking cases. The two Foreign Ministers of Indonesia and Australia noted “the importance of engaging constructively with private industry in a genuine partnership to combat trafficking in our region and promote good practices in their supply chains”.[44] More can be done in this area.

Conclusion

Human trafficking in Southeast Asia is a significant problem. Even if it does not affect Australia directly, its effects are felt through its connection with other types of forced and irregular migration that do concern Australia. Australia has already played a significant role in strengthening the anti-trafficking regime in the region. However, as the analysis in this working paper has shown, within ASEAN states significant gaps remain in the implementation of legislation and policies to combat trafficking, especially in relation to victim protection and sustainable return.

Preventing and prosecuting human traffickers should be the immediate priority for combating trafficking in persons in Southeast Asia. However, greater efforts aimed at protecting victims and reintegrating them back into their communities are also critical to building a sustainable anti-trafficking regime in the region over the long term.

Notes and acknowledgemnts

The author would like to thank the reviewers from the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and the Attorney General’s Department for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper, and Ms Isobel Crealy for her research assistance.

This working paper series is part of the Lowy Institute’s Migration and Border Policy Project, which aims to produce independent research and analysis on the challenges and opportunities raised by the movement of people and goods across Australia’s borders. The Project is supported by the Australian Government’s Department of Immigration and Border Protection. The views expressed in this Working Paper are entirely the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy or the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

[1] The Bali Process has more than 48 members, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as well as a number of observer countries and international agencies.

[2] Jewel Topsfield, “Indonesia Says Bali Process Failure on Refugee Crisis ‘Must Not Happen Again’”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 March 2016.

[3] For the internationally recognised definition of people smuggling, see Article 3(a) of the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, which states that “‘Smuggling of migrants’ shall mean the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident”.

[4] Article 3(a) of the Palermo Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Palermo Protocol) defines trafficking in persons as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation”.

[5] Interview with the UNHCR Malaysia Representative, Richard Towle, July 2016.

[6] Phil Marshall and Susu Thatun, “Miles Away: The Trouble with Prevention in the Greater Mekong Sub-region”, in Trafficking and Prostitution Reconsidered: New Perspectives on Migration, Sex Work and Human Rights, Kamala Kempadoo, Jyoti Sanghera and Bandana Pattanaik eds (Boulder, Colorado; London: Paradigm Publishers, 2005).

[7] US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2016, 56, http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2016/258696.htm. Tier 1 indicates countries whose governments fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking under the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), which are generally consistent with the Palermo Protocol. A Tier 2 ranking means countries whose governments do not fully meet the TVPA’s minimum standards, but are making significant efforts to meet those standards. Tier 2 Watch List means countries whose governments do not fully meet the TVPA’s minimum standards, but are making significant efforts to meet those standards, and for which the number of victims of severe forms of trafficking is very significant, there is a failure to provide evidence of increasing efforts to combat severe forms of trafficking, and efforts to meet the minimum standards was based on commitments by the country to take additional steps over the next year. A Tier 3 ranking means countries whose governments do not fully meet the minimum standards and are not making significant efforts to do so.

[8] Erin Kamler, “Women of the Kachin Conflict: Trafficking and Militarized Femininity on the Burma–China Border”, Journal of Human Trafficking 1, No 3 (2015), 209–234; Caitlin Klein, “Slaves of Sex: Human Trafficking in Myanmar and the Greater Mekong Region”, Righting Wrongs: A Journal of Human Rights 2, Issue 1 (2012), 1–16; Lanau Roi Aung, “Laiza: Kachin Borderlands — Life After the Ceasefire”, in Politics of Autonomy and Sustainability in Myanmar, Walaiporn Tantikanangkul and Ashley Pritchard eds (Singapore: Springer, 2016), 37–55.

[9] Interviews with officers from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and United Nations Action for Cooperation against Trafficking in Persons (UN-ACT) in Bangkok and Yangon, June 2016.

[10] International Labour Organization, “21 Million People Are Now Victims of Forced Labour, ILO says”, Press Release, 1 June 2012, http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_181961/lang--en/index.htm.

[11] Kathy Richards, “The Trafficking of Migrant Workers: What are the Links between Labour Trafficking and Corruption?”, International Migration 42, Issue 5 (2004), 147–168; Janie A Chuang, “The United States as Global Sheriff: Using Unilateral Sanctions to Combat Human Trafficking”, Michigan Journal of International Law 27, No 2 (2006), 437–494.

[12] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “Victim Identification Procedures in Cambodia: A Brief Study of Human Trafficking Victim Identification in the Cambodia Context”, 2013, https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific//Publications/2013/NRM/FINAL_Draft_UNODC_report_Cambodia_NRM.pdf.

[13] Naomi Jiyoung Bang, “Casting a Wide Net to Catch the Big Fish: A Comprehensive Initiative to Reduce Human Trafficking in the Global Seafood Chain”, University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change 17, Issue 3 (2014), 221–255; Ardiles Rante/Greenpeace, “Supply Chained: Human Rights Abuses in the Global Tuna Industry”, November 2015, http://www.greenpeace.org/seasia/th/Global/seasia/2015/png1/Supply-chained_EN.pdf; Kate Hodal, “Slavery and Trafficking Continue in Thai Fishing Industry, Claim Activists”, The Guardian, 25 February 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/feb/25/slavery-trafficking-thai-fishing-industry-environmental-justice-foundation.

[14] IOM, “Counter-trafficking: Regional and Global Statistics at a Glance”, http://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/infographic/CT2015_10_June_2016.pdf.

[15] International Labour Organization, Employment Practices and Working Conditions in Thailand’s Fishing Sector (Bangkok: Asian Research Center for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University, 2013), http://www.ilo.org/dyn/migpractice/docs/184/Fishing.pdf.

[16] Sam Jones, “Trafficked into Slavery on a Thai Fishing Boat: ‘I Thought I’d Die There’”, The Guardian, 16 December 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/dec/16/enslaved-on-thai-fishing-boat-thought-i-would-die-there.

[17] World Vision Australia, Fishy Business: Trafficking and Labour Exploitation in the Global Seafood Industry, 2013, https://www.worldvision.com.au/docs/default-source/school-resources/seafood-industry-factsheet.pdf; Bang, “Casting a Wide Net to Catch the Big Fish: A Comprehensive Initiative to Reduce Human Trafficking in the Global Seafood Chain”; Siroj Sorajjakool, Human Trafficking in Thailand: Current Issues, Trends, and the Role of the Thai Government (Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books, 2013); Supang Chantavanich, Samarn Laodumrongchai and Christina Stringer, “Under the Shadow: Forced Labour among Sea Fishers in Thailand”, Marine Policy 68 (2016), 1–7.

[18] The Walk Free Foundation, The Global Slavery Index, http://www.globalslaveryindex.org.

[19] US State Department, “Male Trafficking Victims”, Fact Sheet, 1 June 2013, http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/fs/2013/211624.htm; ECPAT International, “The Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in South and Southeast Asia: Developments, Progress, Challenges and Recommended Strategies for Civil Society”, November 2014, http://www.ecpat.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy/Regional%20CSEC%20Overview_East%20and%20South-%20East%20Asia.pdf; Jacqueline Joudo Larsen, “The Trafficking of Children in the Asia-Pacific”, Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 415 (Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, April 2011), http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/tandi/401-420/tandi415.html.

[20] Report on the International Conference on Cyberlaw, Cybercrime and Cybersecurity, New Delhi, India, November 2014, https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/cybersecurity-capacity/system/files/Report%202014%20-%20INTERNATIONAL%20CONFERENCE.pdf; Neo Chai Chin, “Human Trafficking ‘A Concern for Every Country’”, Today, 11 April 2014, http://m.todayonline.com/singapore/human-trafficking-concern-every-country.

[21] US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2016, 229, 359, http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258881.pdf.

[22] The Palermo Protocol was adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 55/25, 15 November 2000, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/ProtocolTraffickingInPersons.aspx.

[23] Email correspondence with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 22 July 2016.

[24] US Department of State, “2012 TIP Report Heroes”, in Trafficking in Persons Report: June 2012, 47, http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2012/192362.htm.

[25] Jiyoung Song ed, “A Survey on the Anti-trafficking Legislation in Southeast Asia” (Bangkok: UNHCR, 2014); Jiyoung Song, “A Survey on National Referral Mechanisms in Southeast Asia” (Bangkok: IOM, 2015).

[26] See Article 3(1) of the Law on Human Trafficking Prevention and Combat, Law No 66/2011/QH12, http://un-act.org/publication/view/viet-nams-law-on-human-trafficking-prevention-and-combat-2011/.

[27] Article 6 of the Palermo Protocol, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/ProtocolTraffickingInPersons.aspx.

[28] US State Department, “Methodology”, in Trafficking in Persons Report: June 2016, http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2016/258693.htm.

[29] Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe and Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, National Referral Mechanisms: Joining Efforts to Protect the Rights of Trafficked Persons A Practical Handbook (Warsaw, Poland: OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, 2004), http://www.osce.org/odihr/13967?download=true.

[30] Bali Process, Policy Guides on Identification and Protection of Victims of Trafficking, May 2015, http://www.baliprocess.net/regional-support-office/policy-guides-on-identification-and-protection-of-victims-of-trafficking/; Bali Process Policy Guides on Criminalizing Migrant Smuggling and Trafficking in Persons, August 2014, http://www.baliprocess.net/regional-support-office/policy-guides/.

[31] Song, “A Survey on the Anti-trafficking Legislation in Southeast Asia”; Song, “A Survey on National Referral Mechanisms in Southeast Asia”.

[32] Anne Gallagher, A Shadow Report on Human Trafficking in Lao PDR: The US Approach vs International Law, 2007, http://traffickingroundtable.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/A-Shadow- Report-on-Trafficking-in-Lao.pdf; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “Lao PDR: Ready for Assessment of Anti-Human Trafficking Law and Further Development of Legal Framework with Support by UNODC and the United States”, 10 May 2012, https://www.unodc.org/laopdr/en/stories/anti-human-trafficking.html.

[33] The Walk Free Foundation, The Global Slavery Index, http://www.globalslaveryindex.org, Myanmar.

[34] Australia’s International Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking and Slavery, http://dfat.gov.au/news/news/Pages/australia-launches-international-strategy-to-combat-human-trafficking-and-slavery.aspx.

[35] Interdepartmental Committee on Human Trafficking and Slavery, https://www.ag.gov.au/CrimeAndCorruption/HumanTrafficking/Documents/Report-Interdepartmental-Committee-Human-Trafficking-Slavery-July-2014-June-2015.PDF.

[36] See Trafficking in Persons: The Australian Government Response, 1 July 2013 – 30 June 2014, The Sixth Report of the Interdepartmental Committee on Human Trafficking and Slavery, 62, https://www.ag.gov.au/CrimeAndCorruption/HumanTrafficking/Documents/TraffickingInPersons-TheAustralianGovernmentResponse2013-2014.pdf.

[37] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Australia-Asia Program to Combat Trafficking in Persons (AAPTIP)”, Program Fact Sheet, January 2016, https://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/aaptip-fastfacts.pdf.

[38] Anti-Slavery International, Protocol for Identification and Assistance to Trafficked Persons and Training Kit, 2005, http://lastradainternational.org/lsidocs/16%20Protocol%20for%20Identification%20and%20Training%20Kit.pdf; StopTraffickingSG, “Second Last Words on Right to Work and Legal Protection”, 2 November 2014, https://stoptrafficking.sg/2014/11/02/second-last-words-on-right-to-work-and-legal-protection/; US Department of State, “Victim’s Empowerment and Access”, June 2012, http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/194926.pdf; US Department of State, “The Journey from Victim to Survivor”, June 2014, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/228262.pdf.

[39] Save the Children, Report on Assessing the Return and Reintegration of Victims of Cross-Border Trafficking (Hanoi, Vietnam: February 2008).

[40] Samantha Lyneham, “Recovery, Return and Reintegration of Indonesian Victims of Human Trafficking”, Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 483 (Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, September 2014), http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/tandi/481-500/tandi483.html.

[41] UK Department of Education, “Care of Unaccompanied and Trafficked Children”, July 2014, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/care-of-unaccompanied-and-trafficked-children; US Agency for International Development and Cambodian Centre for the Protection of Children’s Rights, “CTIP Secures the Second Chance at Education for 22 Trafficked Children Forced to Beg in Vietnam”, http://www.ccpcr.org.kh/article/119/prevention-community-education/ctip-secures-the-second-chance-at-education-for-22-trafficked-children-forced-to-beg-in-vietnam.htm.

[42] Email correspondence with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 22 July 2016.

[43] Australian Agency for International Development, “Australia-Asia Program to Combat Trafficking in Persons, Project Design Document”, June 2012, 27–28.

[44] Sixth Ministerial Conference on the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime, Bali, Indonesia, 23 March 2016, Co-Chairs’ Statement, http://www.baliprocess.net/UserFiles/baliprocess/File/BPMC%20Co-chairs%20Ministerial%20Statement_with%20Bali%20Declaration%20attached%20-%2023%20March%202016_docx.pdf.