Getting Singapore in shape: Economic challenges and how to meet them

Without bold adjustments, Singapore’s extraordinary economic performance may prove difficult to sustain.

- The Singapore economy retains many strengths but is facing growing challenges, including to its key regional hub status.

- Singapore’s ability to adjust effectively to these challenges may have weakened compared to the past.

- The major reason for this diminished capacity is that the policy responses required to support a successful adjustment may not be evolving quickly enough. Moreover, the capacity for companies to make more spontaneous bottom-up adjustments seems to be lacking.

Executive Summary

The Singapore economy is at a crossroads, facing challenges in the global environment as well as within its domestic economy. Its location astride the three substantial economic growth regions of China, India, and ASEAN should provide Singapore with continued opportunities to grow. However, the emergence of new technologies, changing structures of international competitiveness, and growing economic nationalism could cause disruptions to its economic potential. Domestically, Singapore confronts the increasing burdens of ageing and slowing population growth, rising costs, weak innovation capacity, and declining productivity growth. The two main adjustment mechanisms needed to deal with such challenges are top-down policy interventions by the government and spontaneous bottom-up adjustments by companies. Without bold adjustments, Singapore’s economic model may not be able to generate adequate responses to overcome its domestic and external challenges.

Introduction

The transformation of the Singapore economy over the past five decades has been impressive, producing rapid economic growth and delivering extraordinary improvements in social welfare. During that period, Singapore has evolved into a developed economy with multiple engines of growth including globally competitive manufacturing clusters, one of the world’s pre-eminent financial and transportation centres, and the location for regional or global headquarters of major corporations.

Today, the economy remains in generally sound shape. However, the Singapore economy faces significant challenges in coming years, including disruptions caused by new technologies, changing structures of international competitiveness, and growing economic nationalism. Domestically, Singapore will need to respond to an ageing population and slowing population growth, rising costs, weak innovation capacity, and desultory productivity growth.

This Analysis assesses the two main adjustment mechanisms for dealing with such challenges: the government’s top-down policy interventions and the more spontaneous bottom-up adjustments by companies. It argues that Singapore’s economic model may not be evolving quickly enough to allow the country to adjust successfully to its domestic and external challenges. It also argues that bolder and more rigorous changes are needed in the policy sphere to overcome these challenges.

Singapore’s economy remains broadly in good shape

Singapore is a key hub in Southeast Asia and in some cases globally for finance, transhipment activities, business services, transportation, and logistics. It also has a robust manufacturing base, which is a key node in the complex value chains that wrap around East Asia. It is involved primarily in high value-added activities that facilitate the smooth flow of people, goods, services, and investments.

In 2017, Singapore was ranked the world’s top maritime capital.[1] It has retained its status as the premier port of call in Southeast Asia as a result of continual upgrades to enhance capacity and efficiency, and despite intense competition from lower-cost rivals. In fact, it recently won back some business it had lost to Malaysian ports such as Port Klang and Tanjung Pelapas.

Singapore has also cemented its position as ASEAN’s premier hub for air transport, surpassing Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport and the Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) in terms of passenger movements for the past four years. In 2017, Changi Airport handled a record 62.2 million passengers, up 6 per cent from 2016. Airfreight throughput also expanded by 7.9 per cent in 2017 to 2.13 million tonnes.[2] However, competition is growing. KLIA’s passenger movements are rising quickly, which in time could rival Changi Airport. Similarly, aircraft movements in Suvarnabhumi Airport have expanded robustly and the challenge it poses can only grow on the back of a 117 billion baht (US$3.7 billion) upgrade scheduled through to 2021, including a third runway.[3]

As a global financial centre, Singapore is ranked fourth behind only London, New York and Hong Kong, and ahead of Tokyo, in the 2018 Global Financial Centres Index.[4] Total assets under management in Singapore stood at S$2.7 trillion in 2016, having increased at a 15 per cent compound annual growth rate over the previous five years.[5]

Singapore is also a favoured location for multinational companies with more than 7000 operating some form of headquarters in the city-state. It also hosts 4200 regional headquarter operations. This is considerably more than Hong Kong with 1389 regional headquarters, Sydney with 533, Tokyo with 531, and Shanghai with 470.[6]

Finally, Singapore continues to leverage off its strategic location in Southeast Asia to remain a key node for transhipment activities. Re-exports constitute an important part of its international trade while transhipments produce positive spillovers into the Singapore economy in industries such as wholesale and retail trade as well as transportation and storage.

Macroeconomic readings are also sound. A few figures illustrate just how robust Singapore’s macroeconomic position is. The current account surplus remains substantial and persistent, averaging 18.2 per cent of GDP over the past five years, as a result of a very high savings rate relative to its investment rate. Inflation has been well behaved over the past few years. In 2017, inflation averaged 0.6 per cent, higher than –0.5 per cent in 2016 and lower than the ten-year average of 2.3 per cent in the period 2008–17.

Fiscal policy remains conservative, generating surpluses over the economic cycle.[7] The government’s net asset position has ballooned over the years, with assets rising from S$483.2 billion in FY2005 to S$705.4 billion in FY2010 to S$941.3 billion in FY2015, or almost three times GDP. At the same time net assets increased from S$126.3 billion in FY2005 to S$186.4 billion in FY2010 to S$293.8 billion in FY2015.

Domestic challenges emerging

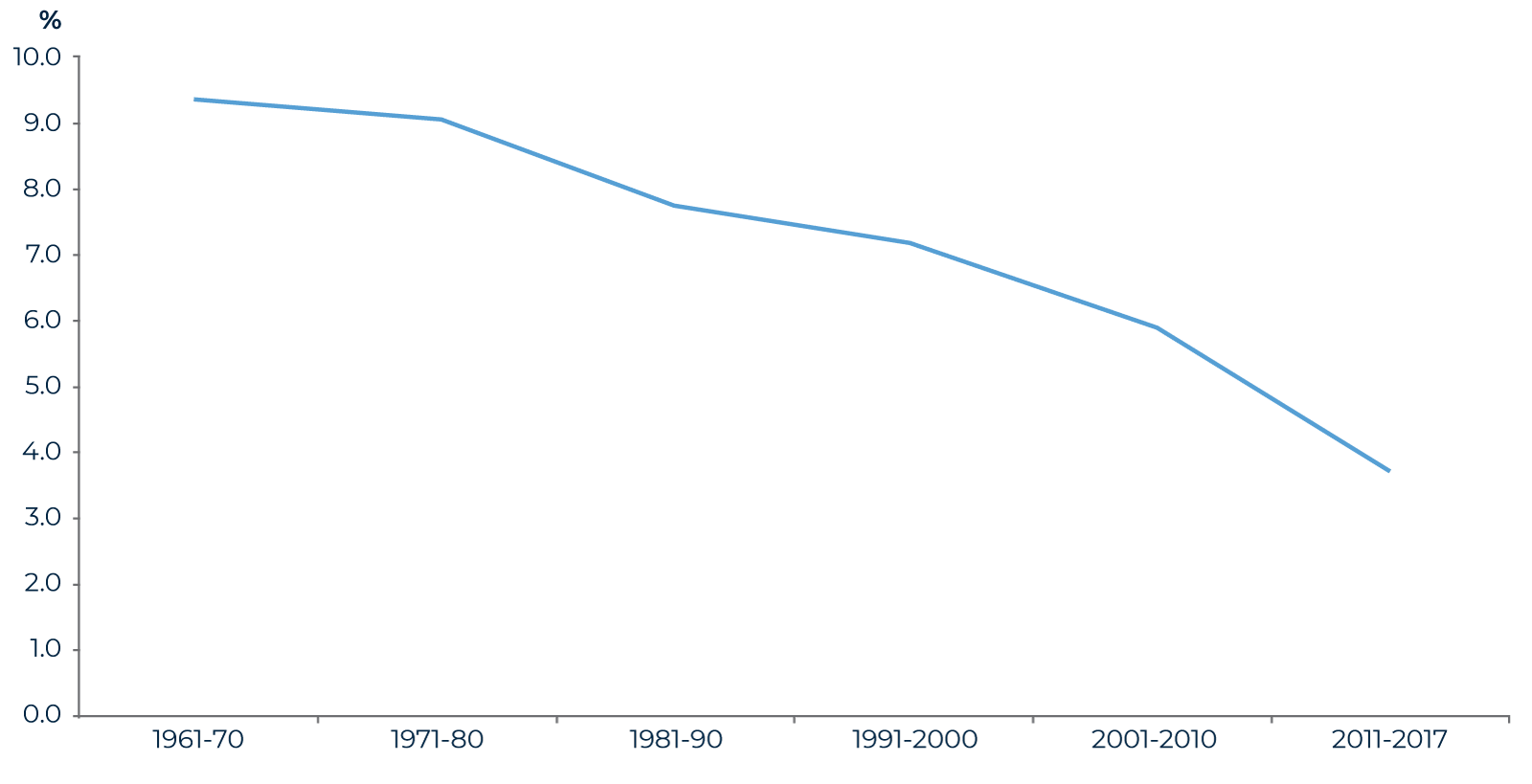

Despite these core strengths, Singapore’s economy needs to continue growing. By how much is a matter of debate. Arguably, to remain an attractive and vibrant economic hub Singapore’s economy needs to grow at around 2 to 3 per cent a year, which is feasible for a high-income country such as Singapore. The challenge, however, is finding where this growth will come from, especially when current growth rates are faltering (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Singapore’s long-term GDP growth

Source: Calculated by Centennial Asia Advisors using CEIC database

Domestically, Singapore’s economy faces three main challenges: population; inequality; and competitiveness.

Population

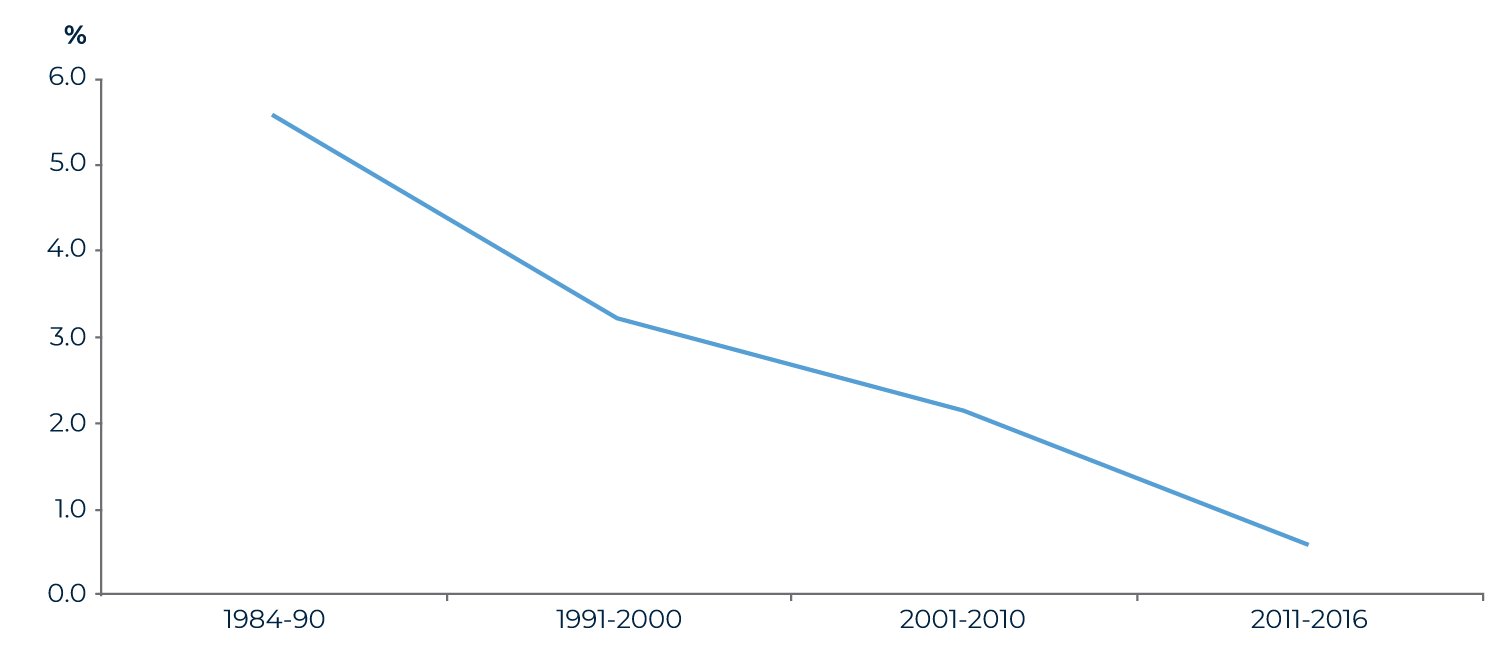

Singapore faces slower growth as the population ages, the workforce stagnates, and productivity weakens. The fertility rate has been falling for many decades, from 5.76 in 1960 to 1.82 in 1980 to 1.60 in 2000. Despite the best efforts of the government to incentivise child rearing, in 2017 the fertility rate fell further to 1.20. Growth in the resident workforce is also decelerating sharply, from a contribution of 4.5 per cent in 1970–80 to 2.1 per cent in 2000–10, and an expected 0.7 per cent in 2010–20 and 0.1 per cent in 2020–30 according to projections made in the 2013 Population White Paper.[8] It may turn negative if falling fertility rates, coupled with tighter immigration guidelines, persist. Productivity growth has not offset the slowdown in workforce growth. In fact, as Figure 2 shows, productivity growth has fallen off sharply in recent years.

Figure 2: Singapore’s labour productivity growth

Source: Calculated by Centennial Asia Advisors using CEIC database

Inequality

A second challenge is inequality. Singapore is a highly unequal society, particularly in comparison with the more successful developed economies such as those in northern Europe. The distribution of the benefits of economic growth remain skewed. This can be looked at in several ways.

The conventional measure of income inequality is the Gini coefficient, which assigns lower scores to more equal societies. Singapore’s Gini coefficient remains high even though it has edged down to 0.458 in 2016, its lowest level in ten years. After taxes and transfers, the corresponding figure is 0.402. The Gini coefficients for the United States and European Union in 2016 were 0.462 and 0.516, respectively. In contrast to Singapore, however, taxes and transfers brought those figures down to 0.390 for the United States and to just 0.308 for the European Union. While inequality is high in the United States and European Union before taxes and transfers, government policy has to a large extent mitigated the inequality in income distribution.

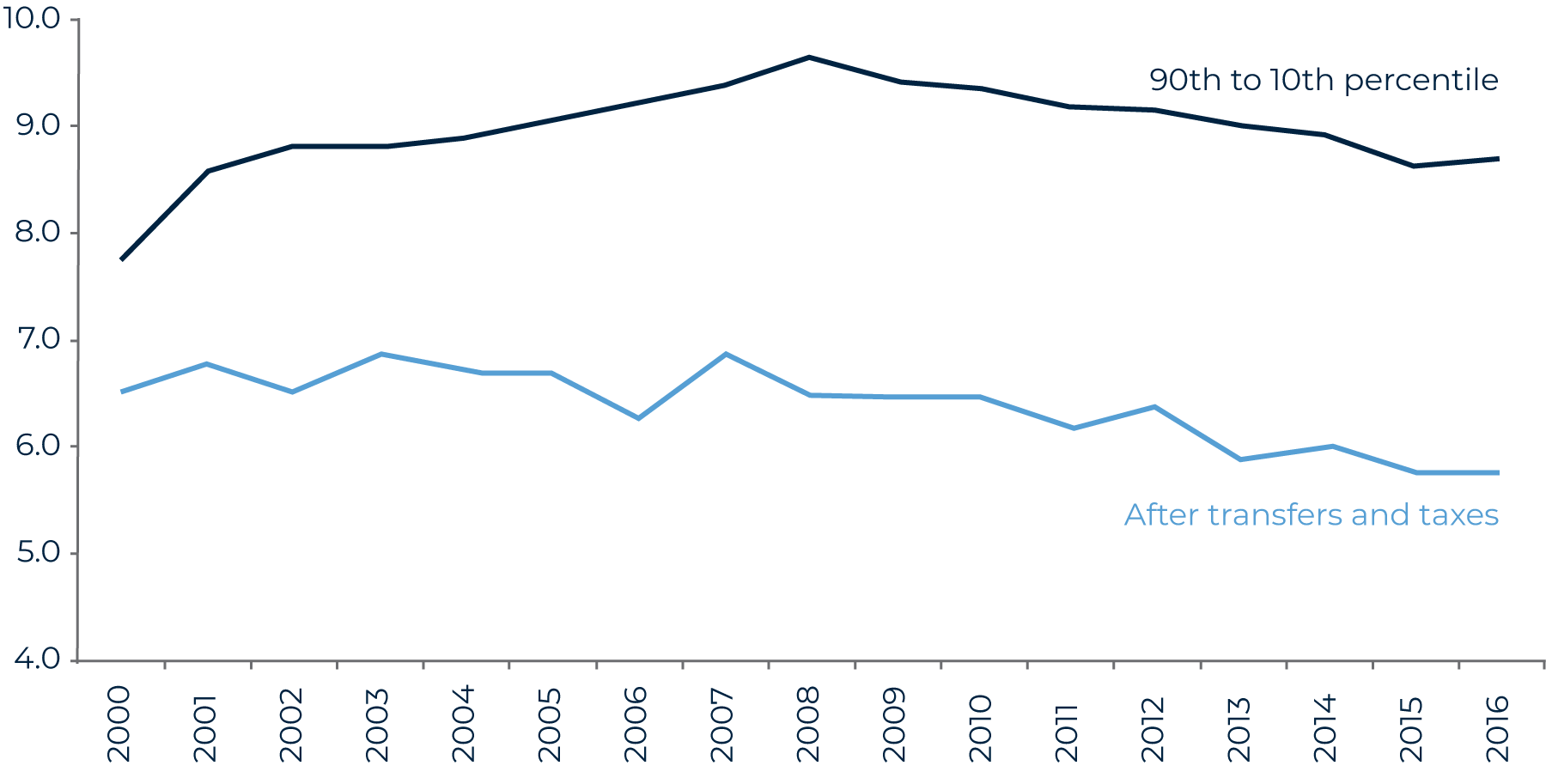

The ratio of the 90th to 10th percentiles of household income from work[9] stood at 8.67 in 2016, lower than the peak of 9.64 reached in 2008. After taxes and transfers, the same ratio was 5.76 in 2016, 5.77 in 2015, and 6.50 in 2008. Looking at a longer time frame, it is clear that there was a worsening of income inequality from 2000 to 2008, which has since only partially reversed. Even so, government mitigation through transfers and taxes is limited in scope compared to other high-income and more developed economies.

Figure 3: Household income from work

Source: Collated by Centennial Asia Advisors from Singstat, Department of Statistics Singapore

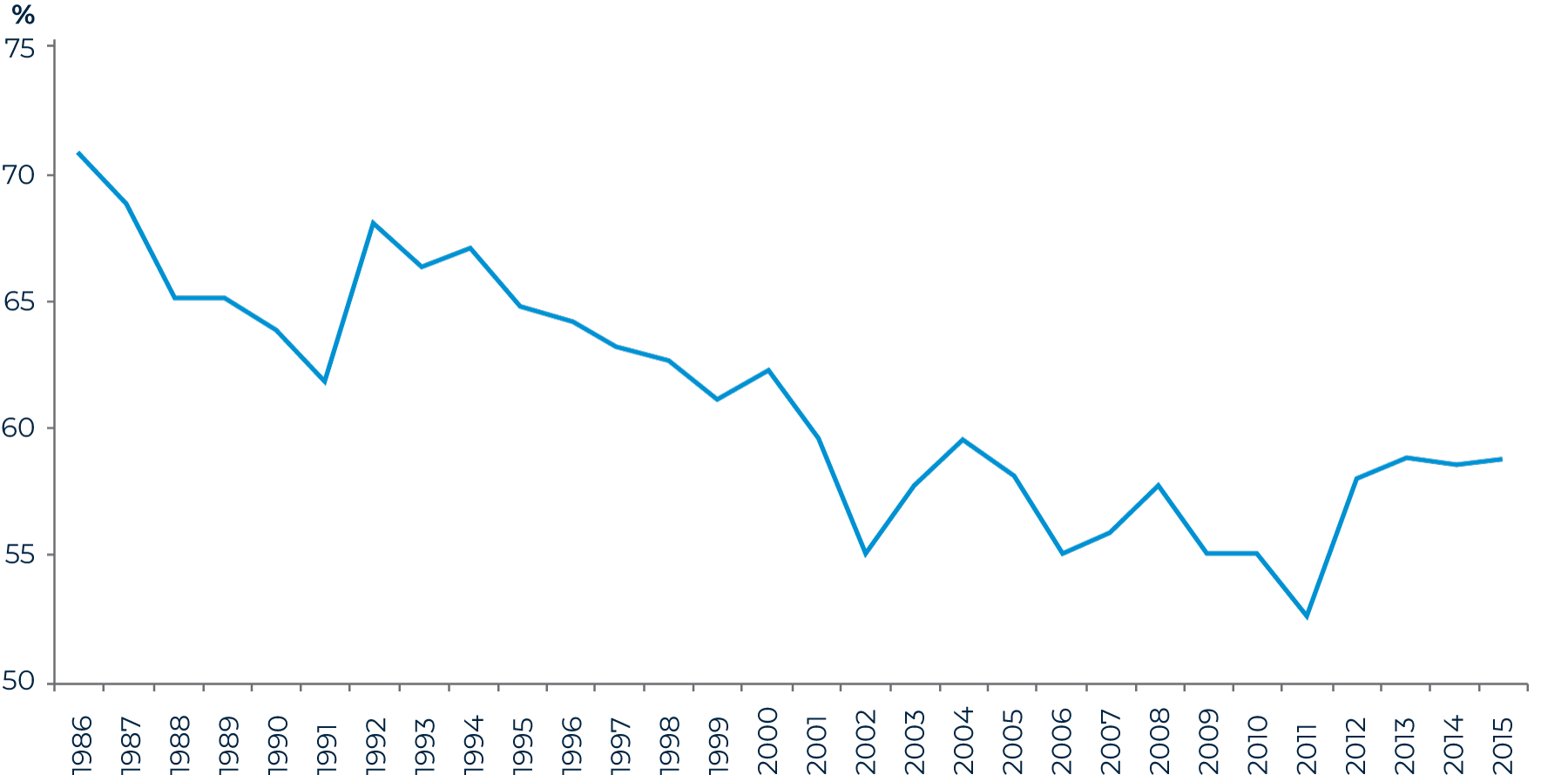

Another way of looking at income distribution, particularly in an economy dominated by foreign capital, is the share of value-added that flows to the indigenous or citizen workforce and to companies that are majority owned by Singapore citizens. As Figure 4 shows, indigenous value-added as a share of total GDP is quite low.

Figure 4: Share of indigenous GDP to total GDP

Source: Collated by Centennial Asia Advisors from Singstat, Department of Statistics Singapore

Note: As the data series has been discontinued, the series has been updated using data provided in response to a parliamentary question

Competitiveness

A third challenge is competitiveness — defined here as the capacity to deliver returns on investment that are superior to competitors. Competitiveness can be looked at in many ways. One approach is based on how Singapore ranks in surveys. Singapore registers impressive rankings on competitiveness surveys (Table 1). It ranks 3rd (2nd in the previous year) in the 2018 World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Index and 2nd (2nd) in the 2018 WEF Ease of Doing Business rankings. In the 2017 INSEAD Global Innovation Index, it ranked 7th (6th).

Table 1: Summary of Singapore’s competitiveness rankings

|

|

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

WEF Global Competitiveness Index |

8 |

7 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

WEF Ease of Doing Business |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

WEF Tourism Competitiveness Index |

– |

16 |

10 |

– |

10 |

– |

10 |

- |

11 |

– |

13 |

– |

|

INSEAD Global Innovation Index |

– |

– |

– |

7 |

3 |

3 |

8 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

– |

Source: Collated by Centennial Asia Advisors using data from World Economic Forum and INSEAD

Singapore also continues to garner an impressive share of global flows of foreign direct investment. Indeed, that share was rising until recently, underlining its competitiveness as an investment destination as well as being a convenient conduit to channel investments into the immediate region, particularly the rapidly growing economies of Southeast Asia. Singapore’s share of global foreign direct investment was 3.5 per cent in 2016, lower than the 4.0 per cent registered in 2015 and 5.6 per cent in 2014 but higher than the long-term average over ten years of 3.3 per cent (2007–16). Similarly, its share of total world exports has been on a very gradual downtrend, albeit from a competitive position. In 2016, Singapore shipped 2.07 per cent of total world exports, down slightly from 2.10 per cent in 2015 and slowly declining from 2.23 per cent in 2011 and 2.24 per cent in 2006.

However, Singapore may be performing less impressively in terms of its cost structure, which can be looked at both in terms of the cost of living for the average Singaporean as well as in terms of business costs. Singapore has become one of the priciest places to live, with a series of surveys ranking it as the most expensive city in the world.

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Worldwide Cost of Living Survey 2018, which tracks a basket of goods across 133 cities worldwide, Singapore is the world’s most expensive city for expatriates to live in, a position it has held for five consecutive years. It remains the most expensive place in the world to own and run a car and the third-priciest place to buy clothes.[10] While the survey is aimed at companies looking to compare relocation costs for expatriates, it compares more than 400 individual prices across 160 products and services, some or most of which are inevitably used by Singapore residents as well.

At the same time, the cost burden on companies operating in Singapore has also increased, compromising competitiveness as business costs are rising faster than in peer countries. In particular, Singapore’s unit labour cost (ULC)[11] has been on a broad upward trajectory since 1980. Unit labour costs grew 1.4 per cent per annum in 2006–10, accelerating to 2.0 per cent in 2011–17 despite slower economic growth. Worse still, Singapore’s ULC growth has outstripped the average ULC growth of the OECD group of economies, with the divergence in growth appearing to widen in the past decade. As a result, corporate sector profitability has taken a hit with return on assets on a gradual but certain decline, falling from 5.3 per cent in 2005 to 4.8 per cent in 2010 and then further to 3.7 per cent in 2015. Return on equity fell at a more rapid pace from 15.3 per cent in 2005 to 15.1 per cent in 2010 to 9.3 per cent in 2015.

Singapore still commands a premium return on capital employed (ROCE).[12] However, that premium has been falling in recent years while the headline ROCE has flat lined (Figure 5). This means that even as competitors in Asia flourish and boost their returns, Singapore has lagged behind and is at risk of diminished competitiveness. This is possibly due to structural constraints such as rising costs, ageing demographics, lacklustre productivity growth, and a dearth of entrepreneurial talent and innovation, which will become increasingly stark.

Figure 5: Singapore Bureau of Economic Analysis ROCE premium

Source: Calculated by Centennial Asia Advisors from Bureau of Economic Analysis data, US Department of Commerce

Growing external challenges

In addition to these domestic issues, Singapore faces a number of external challenges that could threaten its position as a key global and regional economic hub. There are a number of key trends that will make the economic environment that Singapore must operate in more turbulent, while also creating new opportunities for growth.

Singapore sits astride the three greatest economic stories of the twenty-first century — the explosive growth and transformational development of China, India, and ASEAN. As a regional hub well integrated with these economic dynamos, there are opportunities that Singapore could exploit.

Multiple new technological changes are reaching take-off points almost simultaneously. These changes are across many areas including artificial intelligence, robotics and other advanced manufacturing innovations such as renewable energy; digital technologies; and revolutionary biomedical advances such as new therapies and the genomic revolution. These will add new impetus to global growth and could benefit Singapore given its position as a global manufacturing and logistics hub. However, technological disruption is also occurring across industries, and Singapore companies in areas as diverse as media and transportation are already struggling in response.

The structure of competitiveness will change in several ways that are material to Singapore’s prospects. First, rising competition from more countries as, for example, China moves up the value curve, Indian manufacturing becomes more competitive, and emerging economies outside the region such as Mexico improve their competitive positioning through reforms. Second, re-shoring, or the return of production once outsourced to cheaper locations back to the developed economy. Re-shoring is more feasible now as a result of the above technological changes. Finally, developments in the new economy may make scale economies more important as a determinant of competitiveness in areas in which Singapore currently excels such as manufacturing, hub services, and financial markets.

The backlash against globalisation has prompted increasing trade protectionism since the global financial crisis. The Trump administration’s approach to the World Trade Organization, for example, threatens to undermine its dispute settlement mechanism that is crucial in protecting smaller countries such as Singapore from intimidation by bigger economies. Some aspects of Singapore’s recent economic strategy will need to be reviewed as a result. For example, its tax arbitration offer to multinational companies is now viewed with suspicion by large countries that Singapore depends on, as part of the global shift against Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). Singapore’s regional financial, port, aviation, and trading hub have been a source of resentment among some of its neighbours. Over time, Singapore could see more policies to divert business away from its hub.

All of these trends have important implications for Singapore.

There remain substantial opportunities for growth, given Singapore’s links to the growth poles identified above such as its openness to the financial technology (fintech) revolution. The increasing intensity of trade frictions and economic nationalism across the globe could temper but not reverse globalisation. Singapore, as an open economy, will continue to benefit from a rules-based global order.

However, there will be much more competition as well. As Singapore’s neighbours and giant economies such as China and India build their capacities, they will improve their abilities in areas where Singapore is most competent. Most recently, India liberalised its aviation sector to attract more foreign investment, and this reflects more concerted efforts by large emerging economies such as India and Indonesia to increase the ease of doing business and improve their business and investment climate. Competition for export markets and foreign investment looks set to heat up.

Is the regional hub at risk?

Singapore’s status as a regional hub is at the core of its identity. The question is whether this status is now under threat.

Singapore hosts a critical mass of interlocking economic activities that cannot be easily replicated by a challenger. Once established, hubs such as Singapore are difficult to displace. For Singapore, this critical mass includes: high-end financial services; manufacturing activities; business headquarters; superb support services of all kinds; high-value tourism attractions; world-class physical infrastructure combined with best-in-class ‘software’ to run it; credible tax, policy, and regulatory frameworks; free trade agreements that promote connectivity; and all the flows of goods, services, people, and capital that result from these. There are network effects that also help entrench the incumbent’s position. For example, shipping lines and airlines connect in Singapore because other shipping lines and airlines are there, providing the frequency and speed of interchanges vital to their businesses.

These network and critical mass effects should allow Singapore’s port to stave off rising competition from other ports in the region including new facilities being built in Malaysia with Chinese help. However, there are signs that other elements of the regional hub may face more serious challenges in coming years.

As already noted, Changi Airport faces competition from other regional aviation hubs. Singapore’s status as a financial centre is also under threat. In the past two years, 58 companies have delisted from the Singapore Exchange (SGX) compared to 34 listings in the same period. Only a handful have listed on the SGX Mainboard while the rest are on the smaller-cap Catalist board. In 2016, the total initial public offering (IPO) value was S$4.4 billion but the market capitalisation of those who delisted was S$15.5 billion.

Over the past decade, Singapore has attracted global multinational companies and internationalised Chinese and Indian companies to locate their regional headquarters in the city-state. However, regulatory pushbacks in areas such as tax may vitiate the agreements Singapore offered these global firms. Moreover, Singapore’s high cost structure is also deterring more Chinese and Indian firms from placing their international operations there.

The two main contenders for Singapore’s role of regional hub are Hong Kong and Bangkok. Hong Kong has already raced ahead of Singapore in key areas such as equity finance because of the immense scale of opportunity offered by China to Hong Kong but not to Singapore. Over time, the Hong Kong challenge will grow further as its bold infrastructure projects in high-speed rail and bridges to the Chinese mainland link it more seamlessly into the competitive Pearl River Delta economic region. That would give Hong Kong scale economies Singapore could not contemplate. The Pearl River Delta consists of nine cities in the province of Guangdong, as well as the special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau. According to the World Bank, the Pearl River Delta is the world’s biggest megacity with 42 million residents in 2010, surpassing the Greater Tokyo Area in population and size.[13]

Bangkok is emerging as the de facto capital city of the Greater Mekong Sub-Region, with a population of about 220 million and a GDP in excess of US$1 trillion which is also growing rapidly. Moreover, Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor plan effectively integrates the Bangkok metropolitan area with the industrial and transportation nodes of the country’s eastern seaboard, in effect creating a single mega-metropolitan region that will give Bangkok substantial economies of scale, scope, and geographic concentration.

Is Singapore’s economic model up to the challenge?

Singapore’s economic model is characterised by three overarching characteristics: superior organisational ability over its neighbours and competitors; pragmatism and creative problem solving; and deep-seated values such as meritocracy, multiracialism, and dedication to the common man.

These principles provided the foundation for a set of interlinked policies that have served Singapore since its independence. These include:

- Macroeconomic stability through sound monetary policy and prudent fiscal policy complemented by conservative macroprudential regulation of the banking/financial sector.

- Social and political stability as a critical precondition for sustained economic growth.

- Unique tripartite models to minimise frictions in labour relations.

- Public housing employed to entrench multiracialism and ensure that homeowners benefited from rising asset prices as the economy grew.

- An activist government that is proactive in seeking out new opportunities.

- Channelling financial resources into a compulsory pension system to fund development.

- Alliances with foreign capital to spur economic development.

Today, however, Singapore is at a crossroads. The policy choices it makes will determine if it can remain the premier hub in the region, facilitating flows of trade, investment and human capital, while offering high value-added services such as international arbitration and mediation.

Policymakers in Singapore will need to achieve two important goals. The first will be to build greater resilience into Singapore’s economy. In a world that is likely to be marked by volatility and frequent economic and financial shocks, Singapore’s economy needs to be able to absorb shocks and bounce back rapidly. This will allow its economy to recover from unexpected dislocations by drawing on deep reserves of financial strength and prudent buffers built up in more bountiful times.

The second goal will be to build capacity for flexible adjustment. Singapore’s economy needs to develop a capacity to adjust to changing circumstances more spontaneously. This will allow the economy to make its way more smoothly through disruptive changes stemming from technological progress. It will also ensure that Singapore remains in prime position to leverage and benefit from emerging opportunities.

Singapore remains resilient but flexible adjustment lacking

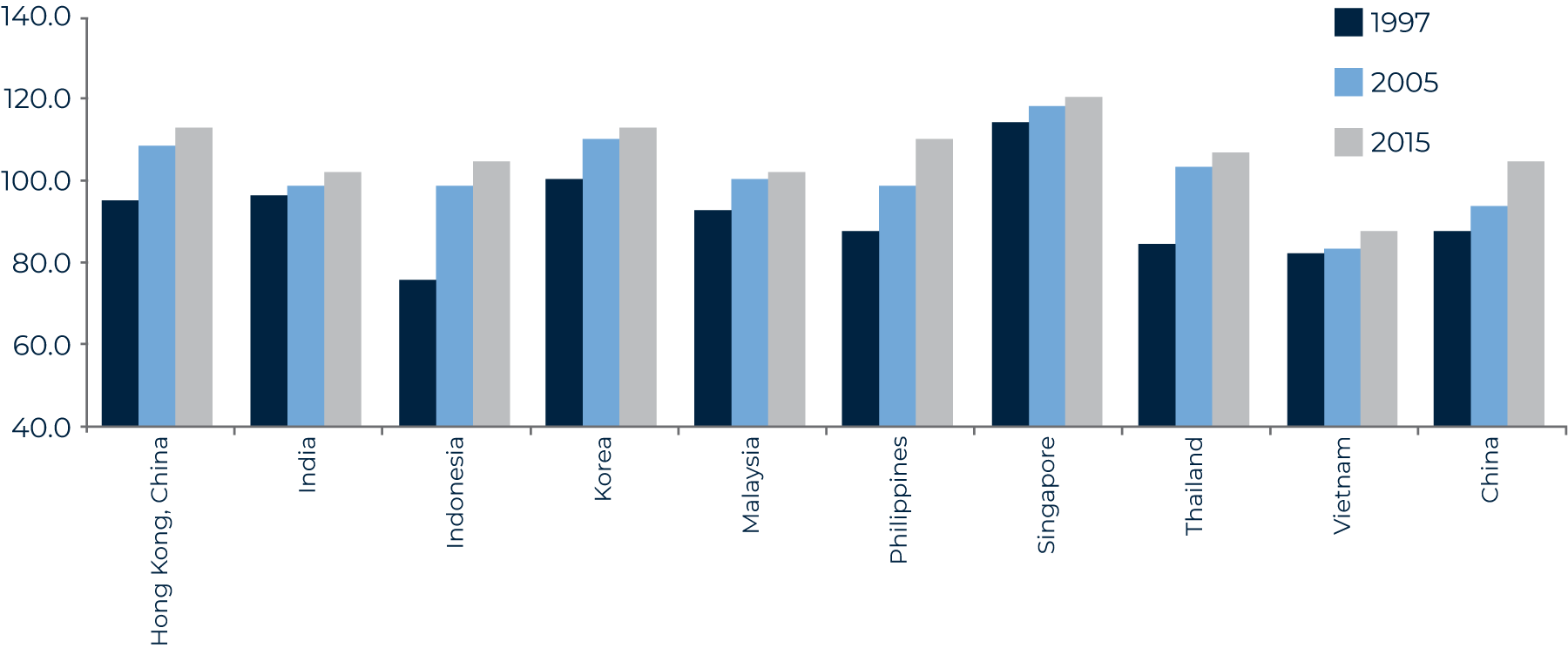

Economic resilience is defined as the balance between shock absorbers and shock amplifiers in an economy. Resilience is a function of the diversity of the economy, the strength of balance sheets, and the capacity of policymaking to swiftly and effectively respond to shocks. The Centennial Resilience Index attempts to measure the capacity of an economy to bounce back from an external shock by quantifying such sources of resilience.[14] As Figure 6 shows, Singapore remains one of the most resilient economies in Asia.

Figure 6: Economic resilience in Asia, 1997–2015

Source: Centennial Asia Advisors

However, Singapore’s capacity for flexible adjustment may not be as strong as its resilience. There are two key components in an economy’s capacity for flexible adjustment. One is top-down, policy-driven adjustment by government and the other is the more spontaneous bottom-up capacity to adjust driven by companies. In terms of Singapore economic policymaking, both of these components are a concern.

Singapore has long been admired for the quality of its government intervention and policymaking. For decades, astute and often bold policy moves helped the economy reinvent itself.

After Singapore gained independence in 1965 in difficult circumstances, policymakers pushed multiple economic strategies. These created a modern industrial capacity where there had previously been little and the start of what was to become a leading global financial centre through the development of an Asian Dollar Market denominated in US dollars. In the late 1970s, as that model outlived its purpose, Singapore embarked on a ‘Second Industrial Revolution’ to push the economy up the value curve. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, policymakers identified and helped develop competence in high-end electronics, such as disk drives, and petrochemicals. At the end of the 1990s, there was another policy-led transformation that established Singapore as a leading global wealth management centre.

However, there are doubts whether the policy establishment is still capable of such responses. Consider, for example, some of the challenges that Singapore has failed to adequately address or policy misjudgements that have created problems. Singapore has known since at least 1984 that it would face a demographic challenge.[15] More than 30 years later and despite substantial government efforts, the trend fall in total fertility rates has not been reversed.

Singapore identified productivity as a challenge in the 1980s and set up the National Productivity Board in response. More recently, the Economic Strategies Committee also highlighted the importance of getting productivity right. Despite this, productivity growth has been weak. Singapore’s leaders realised the need to boost innovation capacity and have mobilised billions of dollars to fund innovation but the results have been meagre.

Moreover, Singapore needs to innovate in order to adjust to this new world but it seems to be struggling to do so. Its performance in a key area — creative productivity — is uneven. As Table 2 shows, Singapore ranks 10th among the 24 economies surveyed in the Creativity Productivity Index. However, its high ranking appears to stem from a strong ability to mobilise inputs (infrastructure, firm dynamics, and financial institutions and governance). In the area that really matters, the efficiency of conversion of inputs to outputs, it ranks much lower, dragging down its overall rank.

Table 2: Top ten economies on the Creativity Productivity Index, 2014

|

Economy |

Overall |

Input |

Output |

|

Japan |

1 |

8 |

4 |

|

Finland |

2 |

6 |

1 |

|

South Korea |

3 |

9 |

8 |

|

United States |

4 |

3 |

3 |

|

Taiwan |

5 |

7 |

9 |

|

New Zealand |

6 |

5 |

5 |

|

Hong Kong |

7 |

2 |

2 |

|

Australia |

8 |

4 |

7 |

|

Laos |

9 |

23 |

17 |

|

Singapore |

10 |

1 |

6 |

Source: Asian Development Bank and Economist Intelligence Unit, Creative Productivity Index: Analysing Creativity and Innovation in Asia, August 2014, https://www.adb.org/news/infographics/creative-productivity-index

The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018, while generally positive about Singapore, highlights a few areas of weakness that could be important as Singapore confronts some of its longer-term challenges. One clear area of concern is innovation. In particular, Singapore did not rank well in areas such as innovation capacity, quality of scientific research institutions, company spending on research and development, and patents (Table 3).[16]

Singapore’s ranking in the related area of technological readiness is also disappointing and could partly explain this weakness in innovation. It is also weak in firm-level absorption of technology and the availability of the latest technologies.[17]

Table 3: Singapore’s ranking on innovation, Global Competitiveness Index

|

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

|

Capacity for innovation |

19 |

20 |

20 |

|

Quality of scientific research institutions |

12 |

10 |

12 |

|

Company spending on R&D |

11 |

15 |

17 |

|

University-industry collaboration in R&D |

5 |

7 |

8 |

|

Government procurement of advanced technology products |

4 |

4 |

5 |

|

Availability of scientists and engineers |

11 |

9 |

9 |

|

Patents, applications/million population |

14 |

13 |

12 |

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Index

Another area where Singapore performs relatively poorly is in business sophistication, defined as the “quality of a country’s overall business networks and the quality of individual firms’ operations and strategies”.[18] Singapore is marked down on almost all the sub-indices in this area especially in local suppliers’ quantity and quality, control of international distribution, and nature of competitive advantage.[19] Given that Singapore has sophisticated and dynamic multinational companies and that most of its government-linked companies operate quite well, this poor ranking almost certainly reflects the weakness of the local private sector.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has echoed some of the weaknesses highlighted in the World Economic Forum report. In a background paper for its Article IV Report on Singapore,[20] the IMF notes that public spending on research and development (R&D) has risen in recent years — from about 2.5 per cent of 1991 GDP under the National Technology Plan 1991–95, to 4.5 per cent of 2016 GDP under the Research, Innovation, and Enterprise Plan 2016–20.[21] While this is likely to help boost Singapore’s R&D capacity and assist to promote Singapore as an attractive location for many R&D-related activities, the IMF pointed to two possible gaps. First, R&D spending by private industry in Singapore is low compared to Singapore’s peers — despite a quarter of a century of immense government effort in boosting R&D. Second, while Singapore is effective at mobilising the inputs required in innovation, actual innovation achievements are relatively disappointing.

The IMF identified several reasons for the weakness in innovation, of which two stand out. One is culture: Singapore’s notorious risk-averse culture could be holding Singaporeans back from achieving more in innovation. Another is the lack of scale economies. Silicon Valley innovators could achieve low unit costs quickly by being able to rapidly scale up in the massive American consumer or business market. Smaller European countries such as Sweden could do so because of the single European market. And Israel could also leverage off the US market because of its extensive links with the United States.[22] However, Singapore’s small domestic market poses challenges to scaling up.

The capacity to respond: Is the current policy approach likely to work?

The past decade has seen some policy misjudgements which may have contributed to Singapore’s economic problems. For example, macroeconomic policy settings may have been set at levels which led to growth well above its potential in the period 2004-11. In particular, foreign labour inflows were liberalised allowing a flood of workers into the economy. The initial effect was to boost growth; however, the longer-term consequences may have been less helpful.

Growth above potential probably explains why Singapore’s inflation was, unusually, above that of its trading partners during that period. The accumulated inflation of the cost structure over that time also probably explains growing complaints by the business sector of rising costs in Singapore.

Even as population growth was deliberately accelerated in that period through a huge increase in immigration, infrastructure such as transportation, hospitals, schools, and the supply of housing did not keep pace. Allowing in cheap foreign labour on a massive scale is likely to have deterred companies from seeking labour-saving productivity gains. It is, therefore, not surprising that productivity growth has lagged.

Moreover, the strategic approach to tackling long-term challenges may not be adequate. The Singapore Government’s latest effort at economic renewal was the establishment of the Committee on the Future Economy (CFE). Commendably, the CFE mounted a massive effort to glean feedback from thousands of Singaporeans as well as from foreign businesses based in Singapore. However, its 2017 report on the future economy[23] carefully restricted itself to existing policy approaches, with few bold new initiatives. Almost all the recommendations involved validating existing policy approaches (see Box A).

Box A: Summary of Recommendations in the 2017 report of the Committee on the Future Economy

Same favoured growth sectors: Companies should look to high-growth sectors in Singapore such as finance, hub services, logistics, urban solutions, healthcare, the digital economy, and advanced manufacturing, with the government taking on a more active role to support growth and innovation. Continued commitment to retaining a large manufacturing base: There will be stepped-up efforts to ensure that manufacturing in Singapore is globally competitive and maintains its share of GDP at 20 per cent over the medium term. No change to economic openness: Not surprisingly for an economy reliant on external demand and foreign investment, the CFE reiterated Singapore’s commitment to economic openness in terms of trade and investment. Singapore will focus on progressing negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) as well as fully utilising the privileges stemming from the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) which is already in effect. No new initiatives for regional integration appear to have been contemplated. Deregulation to spur innovation, digitisation and entrepreneurship: This was one area where some interesting policy moves were hinted at. The government will simplify the regulatory framework for venture capitalists and encourage the entry of private equity firms to provide smart and patient growth capital. It plans to design a regulatory environment supportive of innovation and risk-taking, such as through regulatory sandboxes (testing grounds for new business models not protected by current legislation) and by issuing “no action letters” assuring disrupting companies that they will not be penalised if new ideas come up against Singapore’s infamously rigid regulations. The government will also act as a source of “lead demand” to support up-and-coming industries, particularly those that intersect with strategic national needs. It will set up a Global Innovation Alliance to link Singapore’s institutes of higher learning and companies with overseas partners in major innovation hubs and key demand markets. The government will also promote the adoption of digital technologies across the economy with a dedicated focus on building strong capabilities in data analytics and cybersecurity. Scaling up and internationalising: The government to support the scaling up of high-growth local enterprises as well as the commercialisation of research findings and intellectual property of research institutions. The government will make a big push for agglomeration gains through enhanced international connectivity as well as by developing districts such as Jurong and Punggol into vibrant clusters. Tax reforms: The government to maintain a broad-based, progressive, and fair tax system while remaining competitive and pro-growth. This could be an intriguing reference to a hike in the goods and services tax in the near future. |

At the heart of the CFE’s vision is the Industry Transformation Maps (ITMs), essentially industry-based programs for upgrading selected sectors of the economy. Twenty-three such ITMs have been articulated since they were announced in 2016, covering 80 per cent of the economy. However, businesses have complained that the ITMs were “disconnected from the needs of industry and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and did not have links to other sectors”.[24] These sentiments lend support to concerns that the CFE’s approach will not be sufficient to address the substantial challenges Singapore faces.

Lack of ‘inherent capacity’

Ultimately, economic development is more than simply achieving high rates of GDP growth. For growth to be durable and deliver tangible benefits to its people, it must be accompanied by transformation, expanding the inherent capacity[25] of citizens and the companies that are owned by its citizens to not only create value but to do so in a sustained manner.

Rising, sizeable local companies are relatively rare in the Singapore economy compared to the economic heft of foreign multinational corporations. Due to the multinationals-driven, export-oriented strategy that the Singapore Government has long favoured, export-oriented manufacturing consists primarily of foreign companies, with local enterprises making up the supporting industry infrastructure.

This is in stark contrast with the manufacturing models seen in Germany, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, which incorporate globally competitive local enterprises such as the Mittelstand in Germany, the keiretsu in Japan, the chaebols in South Korea, and the world-leading semiconductor companies in Hsinchu Science Park, Taiwan. In Singapore, local firms tend to be government-linked companies (GLCs) or Temasek portfolio companies (TPCs).

Singapore’s economy has become unbalanced, with disproportionate roles for government-linked and multinational companies and a dearth of non-GLC Singaporean enterprises with regional or global reach. Yet, it is local companies that will play a decisive role in the flexible, bottom-up adjustment necessary for Singapore to adapt successfully in the global economy of the future. Foreign companies will tend to relocate their activity once the economy becomes less attractive. Local companies will have the incentive to stay and adapt.

What has gone wrong?

As Singapore’s economy is so heavily influenced by the outsized role the state plays in it, many of the reasons for the weakened capacity to respond can possibly be traced to issues in the policy sphere.

Part of the problem could be due to narrow performance indicators governing policymaking. For example, in the 2004–11 period an excessive emphasis was placed on generating economic growth rather than overall quality of life in guiding the formulation of policies. Moreover, recent major policy initiatives such as the CFE do not appear to have examined the economy holistically, reviewing the overall structure of the economy and how it has changed. Rather, there appears to be a quick-cut approach, focused on examining a few areas of interest to the leadership.

There has also been an unwillingness to move away from taboos and strongly-held assumptions. It could be argued that generous state-funded infant and child care and more expansive support for parental support such as child allowances explains why some northern European countries have managed to reverse the decline in total fertility rates. The Singapore Government’s initial reluctance to consider such policies and then to only do so belatedly probably explains the failure to mitigate negative demographic trends.

Many observers would agree that to be successful in innovation, Singapore needs to address several areas. The education system needs to be less competitive and more tolerant of late bloomers. However, a reluctance to undertake a bold restructuring of education means the response has been tweaks (many of which are commendable). Others would argue that a freer media and willingness to tolerate dissent is also important for creativity. Here, too, there has been a disappointing reluctance to change.

Part of the weakness could also be traced to problems in the working culture of the bureaucracy. Individually, Singapore’s senior civil servants still rank among the best educated and most honest compared to those in many other countries. However, there are growing concerns about how these individuals behave collectively. There is a tendency to recruit and promote people who are similar to the senior civil servants, with whom the seniors feel comfortable. Those who challenge the views of their seniors are filtered out and do not make it to the top. Consequently, there appears to be far less diversity in the composition of the higher and middle ranks of the key services. The result is a greater risk of groupthink.

The system of training and rotation among different agencies and ministries may not be working as well as previously. For example, scholars serving in the Singapore Armed Forces appear to be parachuted into senior positions for which their training and exposure do not prepare them adequately. There does not seem to be enough emphasis on experience and domain knowledge.

There also appears to be more of a tendency in the bureaucracy to second-guess the wishes of senior civil servants or political leaders and to tell them what they want to hear rather than provide dispassionate and objective advice and analysis. Such risks are present in any bureaucracy but in Singapore the problem seems to have worsened of late.

Conclusion

Singapore’s economy, while still robust and possessing considerable strengths, faces growing challenges. However, Singapore’s ability to adjust effectively to these challenges may have weakened compared to the past.

The major reason for this diminished capacity is that the policy responses required to support a successful adjustment may not be evolving quickly enough. Moreover, the capacity for companies to make more spontaneous bottom-up adjustments seems to be lacking. Unless bolder changes are made to overcome these challenges, Singapore’s extraordinary economic performance may prove difficult to sustain.

Acknowledgements and disclaimer

I would like to acknowledge the assistance I received in writing this paper from my colleague Mr Jason Tan, who provided research support and helped me to crystallise my thinking.

The Lowy Institute acknowledges the support of the Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet for this Analysis.

The views expressed in this Analysis are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute or the Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet.

About the Author

Manu Bhaskaran is Director of Centennial Group International and the Founding Director and Chief Executive Officer of Centennial Asia Advisors. He has more than 30 years of expertise in economic and political risk assessment and forecasting in Asia. Before joining the Centennial Group, he was Chief Economist for Asia of a leading international investment bank and managed its Singapore-based economic advisory group. Mr Bhaskaran serves as Member of the Regional Advisory Board for Asia of the International Monetary Fund; Senior Adjunct Fellow, Institute of Policy Studies; Council Member of the Singapore Institute of International Affairs; and Vice-President of the Economics Society of Singapore.

Notes

[1] Erik Jakobsen, Christian Svane Mellbye, Shahrin Osman and Eirik Dyrstad, “The Leading Maritime Capitals of the World 2017”, Menon Economics, Publication No 28/2017, https://www.menon.no/wp-content/uploads/2017-28-LMC-report.pdf.

[2] Changi airport Group, “A Record 62.2 Million Passengers for Changi Airport in 2017”, Press Release, 23 January 2018, http://www.changiairport.com/corporate/media-centre/newsroom.html#/pressreleases/a-record-62-dot-2-million-passengers-for-changi-airport-in-2017-2386732.

[3] Kyunghee Park, “Boeing, Airbus Eye 16,000-Plane Jackpot as Asia Gets Airborne”, Bloomberg, 5 February 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-04/asian-demand-for-16-000-planes-spells-jackpot-for-airbus-boeing.

[4] Z/Yen Group and China Development Institute, “The Global Financial Centres Index 23”, March 2018, http://www.longfinance.net/images/gfci/GFCI_23.pdf.

[5] Monetary Authority of Singapore, “2016 Singapore Asset Management Survey”, September 2017, 6, http://www.mas.gov.sg/~/media/MAS/News%20and%20Publications/Surveys/Asset%20Management/2016%20AM%20Survey%20Report.pdf.

[6] Singapore Economic Development Board, “Headquarters: Scaling Up from Singapore”, 21 June 2017, https://www.edb.gov.sg/en/news-and-resources/insights/headquarters/scaling-up-from-singapore.html; Cushman & Wakefield, “APAC Regional Headquarters”, 2 April 2016.

[7] This is the case even on the accounting method that Singapore uses to depict its fiscal position, which underestimates revenues given that the hefty receipts from government land sales are not included in the revenues.

[8] National Population and Talent Division, Prime Minister’s Office, A Sustainable Population for a Dynamic Singapore: Population White Paper (Singapore Government, January 2013), https://www.strategygroup.gov.sg/docs/default-source/Population/population-white-paper.pdf.

[9] The 90/10 ratio is a measure of inequality which is the ratio of incomes at the top (90th percentile) versus the bottom (10th percentile) of the workforce.

[10] The Economist Intelligence Unit, “Worldwide Cost of Living 2018”, March 2018, http://www.eiu.com/topic/worldwide-cost-of-living.

[11] According to Singstat, Department of Statistics Singapore, unit labour cost is defined as the average cost of labour per unit of output and is computed as total labour cost per unit of real gross value-added. Total labour cost consists of compensation of employees, labour income of the self-employed, other labour-related costs (e.g. Foreign Worker Levy and net training costs) incurred by employers, and wage subsidies (e.g. Wage Credit Scheme and Jobs Credit Scheme) that are provided to employers. Wage subsidies reduce labour costs to employers and are netted off from total labour cost.

[12] The premium for a country is the difference between the country’s return on capital employed (ROCE) and the average Asia-Pacific ROCE.

[13] World Bank Group, East Asia’s Changing Urban Landscape: Measuring a Decade of Spatial Growth (Washington DC: World Bank, 2015), 21–22, https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Publications/Urban%20Development/EAP_Urban_Expansion_full_report_web.pdf.

[14] For more on the Resilience Index, see Jack Boorman et al, “The Centennial Resilience Index: Measuring Countries’ Resilience to Shock”, Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies 5, Issue 2 (2013), 57–98.

[15] Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew outlined this challenge as early as 1984 in his National Day Rally Speech.

[16] World Economic Forum, The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018 (Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2017), 262–263, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2017-2018/05FullReport/TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2017–2018.pdf.

[17] Ibid, 263.

[18] Ibid, 319.

[19] Ibid, 263.

[20] International Monetary Fund, Staff Report for the 2017 Article IV Consultation with Singapore, IMF Country Report No 17/240, July 2017, http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2017/07/28/Singapore-2017-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-45144.

[21] International Monetary Fund, Singapore, Selected Issues Paper, IMF Country Report No 17/241, July 2017, 15, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2017/07/28/Singapore-Selected-Issues-45148.

[22] Ibid, 16.

[23] Committee on the Future Economy, Report of the Committee on the Future Economy: Pioneers of the Next Generation (Singapore: Government of Singapore, 2017), https://www.gov.sg/~/media/cfe/downloads/mtis_full%20report.pdf.

[24] Vivien Shiao, “Industry Road Maps May Not Meet Needs of SMEs: Panellists”, The Straits Times, 10 January 2018, http://www.straitstimes.com/business/economy/industry-road-maps-may-not-meet-needs-of-smes-panellists.

[25] Inherent capacity can be seen as the ‘software’ ingrained within a nation’s indigenous workers and companies that incorporates the coding for successful economic activity. This includes accumulated financial capital, workers’ skills, locally owned intellectual property and capacity for innovation, the accumulated intangible experience, management and operating processes, and knowledge of markets that are stored in Singapore-owned companies or other entities such as research centres, think tanks, and industry associations. It would also include the adapted cultural habits and institutions in society that enable economic agents to work together to produce results, including, more broadly, social resilience and cohesiveness.

Photo: Bryan Lee/Flickr