Indonesia in the South China Sea: Going it alone

While Indonesia under Jokowi can be expected to continue to take unilateral action to reinforce the Indonesian position around the Natuna Islands, Jokowi has not played an active diplomatic role on the broader South China Sea issue. In the longer term, Indonesia is better off investing in diplomatic leadership. Photo: Getty Images

- Under President Jokowi, Indonesia’s approach to the South China Sea disputes has moved from that of an active diplomatic actor seeking a peaceful resolution to the broader disputes, to one primarily focused on protecting its own interests around the Natuna Islands while not antagonising China.

- The shift in the Indonesian position has been driven by an increase in Chinese incursions around the Natunas, Jokowi’s lack of interest in a major diplomatic role, as well as Jokowi’s goal of attracting Chinese investment for his signature infrastructure projects.

- Jokowi’s approach to the South China Sea and interest in better relations with Beijing could sour, however, if China does not deliver on its investment pledges, becomes overly assertive around the Natuna Islands, or takes an interventionist stance on the protection of ethnic Chinese Indonesians from communal violence.

Makalah ini juga tersedia dalam Bahasa Indonesia.

Executive summary

Under President Jokowi, Indonesia’s approach to the South China Sea disputes has moved from that of an active player in efforts to find a peaceful solution to the broader disputes, to one primarily focused on protecting its own interests around the Natuna Islands while not antagonising China. The shift in the Indonesian position has been driven by an increase in Chinese incursions around the Natunas, Jokowi’s lack of interest in regional diplomacy, as well as his goal of attracting Chinese investment for his signature infrastructure projects.

Indonesia’s more unilateral approach leaves the other countries of Southeast Asia more isolated and exposed to Chinese diplomatic pressure than they were under Jokowi’s predecessor, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. This reduces the possibilities for collective action among Southeast Asian governments eager to fend off further Chinese pressure, leading to a more acute great power rivalry in the region. Jokowi’s approach to the South China Sea and interest in better relations with Beijing could sour, however, if China does not deliver on its investment pledges, becomes overly assertive around the Natuna Islands, or takes an interventionist stance on the protection of ethnic Chinese Indonesians from communal violence.

Introduction

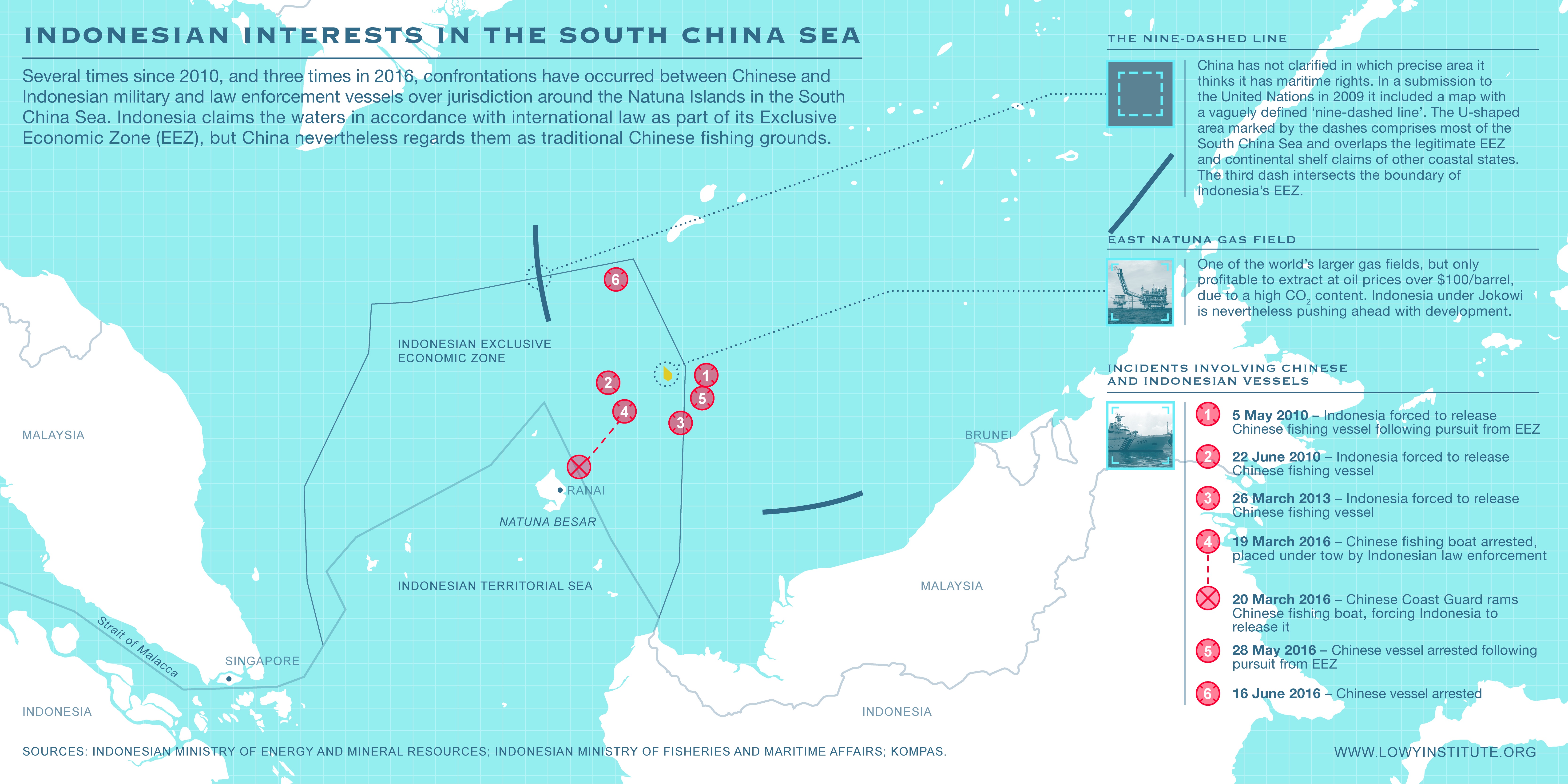

On 17 June 2016, a small Indonesian Navy corvette, the KRI Imam Bonjol, encountered at least seven Chinese fishing boats and two much larger Chinese Coast Guard vessels in Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) near the remote Natuna Islands.[1] The Natunas are the northernmost point of this part of the Indonesian archipelago, between Borneo and the Malaysian Peninsula, stretching into the far southern end of the South China Sea. Neighbours have long acknowledged the waters north of the Natunas as part of Indonesia’s EEZ, but the Chinese Foreign Ministry has since the 1990s implied — and in 2016 for the first time openly declared — that they are “traditional Chinese fishing grounds”.[2]

The Imam Bonjol gave chase and, after firing warning shots, seized one of the fishing boats and arrested its crew for illegal fishing, before returning to its run-down base at Ranai on the island of Natuna Besar. The incident was the latest in a series of encounters in the area between Indonesian authorities and Chinese vessels. Although the Chinese Coast Guard did not risk a confrontation by attempting to prevent the arrest, as it had during a similar incident in March 2016, the Chinese Foreign Ministry protested vigorously and publicly the next day.[3]

On 23 June 2016, Indonesian President Joko Widodo, who prefers to be known by the portmanteau Jokowi, flew to Ranai, the first time an Indonesian president had visited Natuna Besar. Wearing a bomber jacket, he boarded the Imam Bonjol, named after a nineteenth century anticolonial hero, where he convened a limited Cabinet meeting. There, they discussed the defence and economic development of the area, which is rich in fisheries and natural gas.[4]

Jokowi’s visit to Natuna was intended to send a signal to the Chinese leadership in Beijing that Indonesia would protect its sovereign rights in its EEZ, by force if necessary. Inside and outside Indonesia, analysts critical of China’s actions in the South China Sea praised what they characterised as a stiffening of Indonesia’s approach to its relationship with China.[5]

But as this Analysis argues, Jokowi’s visit obscures the more accommodating stance that his administration has taken towards China as it pursues Chinese infrastructure investment. Despite Jokowi’s resolute rhetoric on maritime rights, Indonesia has sought to ensure its campaign against illegal fishing does not target Chinese vessels; and in regional diplomacy, Jokowi’s administration has been eager to ensure it does not offend Beijing. Indonesia’s position matters, because as the largest and most populous country in Southeast Asia, it has traditionally been regarded as first among equals within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), providing the region with important diplomatic leadership on issues such as the South China Sea disputes. As a result, even marginal changes in Indonesia’s approach can have outsized consequences for the region.

This Analysis traces the geographical, legal, and historical dynamics of the dispute between China and Indonesia in the South China Sea. It places these dynamics in the context of Jokowi’s broader foreign policy and his focus on infrastructure investment. It details the ways in which Indonesia has sought to avoid offending Beijing on issues of illegal fishing and regional diplomacy regarding the South China Sea. It examines three reasons why Jokowi’s new approach might not last. Finally, it argues that the change in Indonesia’s approach has had a negative effect on regional stability and Indonesia’s long-term interests.

New neighbours: Indonesia and China around Natuna

While Chinese claims and actions in the South China Sea have touched all of the sea’s littoral countries, the Chinese dispute with Indonesia is often overshadowed by more fraught disputes with countries closer to the Chinese mainland, in particular the Philippines and Vietnam.

Indonesia and China's dashed line

Like many other territorial disputes in the South China Sea, the origin of the contemporary dispute between China and Indonesia can be found in the infamous 1947 map drawn by Nationalist Chinese diplomats featuring a dashed line encircling much of the South China Sea. The geography of the dashed line on Chinese maps varies; however, in every version, one of the dashes intersects the northern boundary of Indonesia’s declared EEZ north of the Natunas, around 1400 kilometres from the Chinese mainland.[6] The waters in the disputed area are an important fishery and the seabed below is home to large natural gas reserves.[7]

Beijing has never offered a clear explanation of the nature of the claim implied by the dashed line. Chinese statements at their most expansive have implied that it outlines a claim to a territorial sea, or to an EEZ; other statements have implied that the line is merely a guideline illustrating Chinese claims to fishing rights within the line, or to islands and rocks within it but not to any separate maritime entitlements.[8] Unlike other countries in the region affected by China’s dashed line, China and Indonesia do not dispute sovereignty over any land features. For Indonesia, therefore, China’s maritime claims within the dashed line are the primary concern.

Indonesian officials have repeatedly asked China to clarify the nature of the dashed line claim since first becoming aware in 1993 that it encompassed part of Indonesia’s EEZ.[9] In July 2010, Indonesia wrote in a note verbale to the UN Secretary General that the line “clearly lacks international legal basis”, and that it risks upending the United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS).[10] For the most part, however, Indonesia has taken the view that, because under international law any claim to maritime entitlements such as a territorial sea, an EEZ, or fishing rights cannot be legitimised without some reference to land features, and because there are no disputes between China and Indonesia over the sovereignty of land features, the line’s existence is best ignored. There has been a consensus in Jakarta that disputing it would offer it a legitimacy that it does not deserve.[11]

Indonesia derives a key benefit from its reluctance to acknowledge the dashed line: it allows Indonesia to treat any disagreements arising from Chinese actions in the overlapping areas as unconnected to the disputes of other countries in the region that have arisen from Beijing’s dashed line. Indonesia therefore argues that it is a non-claimant in the broader South China Sea disputes, a status that Indonesian officials have long said allows it to play the role of an “honest broker” in negotiations over those disputes, for example by hosting informal “workshops” on the issue from 1990 to 2014.[12] However, after more than a quarter of a century, it is not clear what results Indonesia’s services in these negotiations have delivered.[13] Moreover, Indonesia’s reluctance to more openly challenge the dashed line weakens international efforts to push back against expansive Chinese claims, even as it allows Indonesia to avoid difficult conversations with China.

Encounters at sea

On at least three occasions in 2010 and 2013, Indonesian vessels attempting to arrest Chinese fishing boats in the South China Sea were ordered by Chinese law enforcement vessels to let the Chinese boats in Indonesian custody go free. In response to threatening behaviour by their Chinese counterparts, the Indonesian vessels complied.[14] Chinese vessels have continued to fish in Indonesia’s EEZ around the Natunas, and in recent months they have been shadowed by Chinese Coast Guard vessels, as they were in the incidents in 2010 and 2013. Three encounters between Indonesian and Chinese vessels in 2016 are worth noting.

First, on 19 March 2016, an Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries vessel caught a Chinese trawler fishing in its EEZ. The vessel gave chase, firing warning shots, and seized the boat, towing it back to port. As the two boats approached Indonesia’s territorial sea nearly 12 hours later, a large Chinese Coast Guard vessel appeared on the horizon, demanding the fishing boat’s release. When the Indonesian vessel did not comply, the Chinese Coast Guard vessel rammed the Chinese boat under tow, forcing the Indonesian authorities to release it.[15]

Chinese diplomats phoned their counterparts in Jakarta to urge Indonesia to keep the incident quiet; however, before her counterparts from the Foreign Ministry could stop her, Indonesia’s Minister for Marine Affairs and Fisheries Susi Pudjiastuti held a press conference to detail the incident.[16] This was a departure from the earlier incidents in 2010 and 2013, when Indonesia chose not to publicise the encounters. Going public introduced domestic political pressure to take a stronger stand against Chinese illegal fishing.

In response, Defense Minister Ryamizard Ryacudu announced plans to deploy three frigates, five F-16 fighter jets, and an army battalion to Ranai, telling reporters: “Natuna is a door; if the door is not guarded, then thieves will come in.”[17] Indonesia also launched a vigorous if poorly coordinated diplomatic protest, as the fisheries minister, foreign minister, and defence minister all announced that they would summon the Chinese ambassador. For its part, China argued that the area was a “traditional Chinese fishing zone”, a claim that elicited further protests from Jakarta.[18]

Yet Indonesian officials also showed signs of caution, with Jokowi instructing his coordinating minister for politics, law, and security, Luhut Panjaitan, to remember that China was “a friend of Indonesia”, and dispatching him to Beijing six weeks later for meetings on the disputes and Chinese investment.[19] On his return, Luhut sought to discourage notions of a breach, telling reporters that Indonesia would seek to cooperate with China in the fisheries around Natuna.[20]

Only a few weeks after Luhut’s return, on 27 May, the Indonesian Navy frigate KRI Oswald Siahaan found a Chinese trawler in a similar location, again giving chase and firing warning shots before arresting eight fishermen and seizing the boat just east of Indonesia’s EEZ boundary.[21] This time, nearby Chinese Coast Guard vessels did not intervene, although China’s Foreign Ministry subsequently protested the arrest.[22] The 17 June incident, recounted in the introduction to this Analysis, followed three weeks later. Jokowi made a second visit to Ranai for the close of the large-scale Air Force exercises in October.[23]

Fisheries Minister Susi Pudjiastuti told reporters in September 2016 that there had been no further incursions by Chinese fishing boats into the Indonesian EEZ since the 17 June incident, which may suggest that measures taken by Indonesia have had a deterrent effect.[24] It is also possible that the movement of Chinese fishermen and their coast guard escorts are seasonal. Of the six known incidents between Indonesian and Chinese vessels, four occurred during China’s ban on fishing in the northern part of the South China Sea from mid-May to 1 August. Some scholars have argued that the ban pushes Chinese fisherman south to the Spratlys, and the same logic may apply to the Natunas.[25]

Changes in Indonesian foreign policy under Jokowi

In order to safeguard its independence and territorial integrity, Indonesia has generally sought to manage the distribution of power in Southeast Asia. Former Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa referred to this strategy as one of “dynamic equilibrium”, through which Indonesia would seek to shift its diplomatic weight between China and the United States in order to maintain a balance between the two.[26] In doing so, it has long endeavoured to avoid the perception that it has aligned too closely with either the United States or China, even where this has meant taking positions that seem to be inconsistent with its own self-interest on specific issues.

With regard to the South China Sea dispute, this has meant that as US concern about the dispute has risen, beginning with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s intervention at the ASEAN Regional Forum in Hanoi in 2010, Indonesia has become less likely to affiliate itself with US positions on the issue, even when doing so may have served Indonesian interests. For example, Jokowi’s predecessor, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, rebuffed Chinese entreaties that the South China Sea be kept off the agenda at the East Asia Summit in 2011 in Bali — but he also refused US suggestions that he facilitate the meeting in a way that isolated Beijing, despite his own concerns about Chinese behaviour.[27]

Alongside this continuity, however, there have also been important changes to the conduct of Indonesian foreign policy under Jokowi, which affects how it perceives its interests vis-à-vis the great powers, and its interests in the South China Sea.

Yudhoyono came to the presidency in 2004 with a long-standing interest and substantial experience in foreign affairs. Over ten years in office, he sought to elevate Indonesia’s standing on the world stage, and improve Indonesia’s relations with foreign countries. Yudhoyono advocated a policy of a “thousand friends, zero enemies” and an “all directions foreign policy”.[28]

Towards the end of his presidency, a number of Indonesian public figures began to voice a critique of Yudhoyono’s foreign policy. Indonesia, they argued, had become weak under Yudhoyono, whose globetrotting summit diplomacy they said had been little more than an ego trip. Some even implied that he had sought to avoid offending foreign governments in order to ensure their praise; citing, for example, his refusal to order the executions of foreign drug traffickers for years after their convictions, and the failure to better protect Indonesian migrant workers overseas.[29]

Unlike Yudhoyono, Jokowi came to office in 2014 with no diplomatic or military experience, or any strong views about the abstract concepts upon which the practice of Indonesian foreign policy is based, such as dynamic equilibrium or the centrality of ASEAN in regional diplomacy. Rather, he burst onto the national stage as a can-do mayor, developing a reputation for producing quick results. In his campaign for president, he promised to focus on accelerating Indonesia’s economic development.

Viewing diplomacy as an elitist endeavour overly concerned with abstract concepts, Jokowi has been particularly sceptical of the utility of multilateral summit diplomacy, which he associated with Yudhoyono’s globetrotting style.[30] When he took office, foreign policy became subordinate to a renewed emphasis on economic development. He instructed Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to focus on ‘down-to-earth diplomacy’ (diplomasi membumi), defined as diplomacy that would be ‘useful to the people’, with a particular focus on trade and investment.[31] Likewise, he launched a crackdown on illegal fishing by foreign vessels, over the objection of diplomats that it would damage Indonesia’s relationship with its neighbours. China’s role in each of these initiatives is revealing.

Jokowi’s infrastructure agenda

At the centre of Jokowi’s developmentalist agenda has been a focus on attracting infrastructure investment. The National Development Planning Agency estimates that Indonesia needs around $450 billion in infrastructure investment over the five years from 2015 to 2019, but that the government can only provide a third of that.[32] Indonesia has struggled in recent years to attract private foreign direct investment for major infrastructure projects, held back by a reputation for corruption and slow, overlapping regulatory processes that make the acquisition of land and permits difficult.[33]

To fill that infrastructure investment gap, Jokowi has looked to Beijing. Jokowi’s advisers say he admires China’s rapid development, and sees Chinese President Xi Jinping as a fellow results-oriented leader.[34] China’s extraordinary push to fund infrastructure projects through its Maritime Silk Road initiative and the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) present an opportunity to secure funding on better terms than could be acquired on the private market. While Jokowi and his advisers are sceptical of most multilateral financial institutions, they cite China’s relatively small investment in Indonesia at present, and the low rate of announced Chinese projects in Indonesia that come to fruition, and argue that with a little extra effort, much more Chinese investment could be secured.[35]

The Jokowi administration’s enthusiasm for Chinese investment was evident when, in a closely watched contest, it awarded the contract for a $6 billion high-speed rail line between Jakarta and Bandung to a consortium of Chinese and Indonesian state-owned enterprises in September 2015. While Japanese government-backed feasibility studies for the line had begun in 2011, the Chinese Government had first offered assistance in building the line only a few months before the contract was awarded, in April 2015. The Japanese bid for the project was considered superior on technology and the terms of financing, but the Chinese bid offered a faster construction timeline, at a lower cost, and — most critically — did not require a guarantee of funding by the Indonesian Government.[36]

Jokowi’s overall focus on speedy delivery and attractive financing suggest that the rail line will not be the last time that he looks to Beijing for investment in marquee infrastructure projects. However, as outlined later in this Analysis, Jokowi’s enthusiasm for Chinese investment could diminish if China cannot deliver on its infrastructure investment pledges.

Crackdown on illegal fishing

One of the more prominent manifestations of Jokowi’s comparatively strident approach to the pursuit of the national interest has been his administration’s campaign to combat illegal foreign fishing in Indonesian waters. Starting in December 2014, foreign vessels caught fishing illegally have been impounded, their crew arrested, and some of the vessels scuttled or dramatically blown up for the cameras. Polls have indicated that the crackdown is among the Jokowi administration’s most popular policies.[37] Given the high-profile episodes of illegal Chinese fishing discussed earlier, one might expect this approach to have introduced friction into the relationship between Jakarta and Beijing, and some foreign diplomats and analysts have predicted as much. However, this has not been the case.

Under the program, Indonesia has blown up 234 foreign fishing boats, but has handled Chinese boats far more delicately than other countries’ vessels. In December 2014, a large vessel with a Chinese crew was impounded by customs officials in Merauke, Papua, far from the South China Sea. While Fisheries Minister Susi Pudjiastuti argued that the vessel should be sunk, her Cabinet colleagues maintained that doing so would anger China.[38] After the Cabinet determined that the boat should not be sunk, Susi continued to argue that Indonesia sink a Chinese vessel, to demonstrate that no nation’s vessels could operate with impunity. In May 2015, Indonesian officials quietly scuttled a Chinese fishing boat that had been caught six years earlier.[39] No Chinese vessels have been sunk since.[40] Plans to sink several Chinese vessels along with dozens of other foreign vessels on Indonesia’s independence day, 17 August 2016, were cancelled at the last minute.[41]

Indonesian reluctance to anger China in law enforcement, moreover, has been echoed by Indonesian restraint in multilateral diplomatic forums.

The Indonesian void in multilateral diplomacy

Jokowi’s emphasis on delivering tangible domestic economic results and his associated scepticism of multilateral summit diplomacy has led to less active Indonesian diplomacy than under Yudhoyono, including in ways that have benefited Beijing. The change has been most noticeable within ASEAN, which had come to rely on Indonesian leadership in advancing regional norms and forging consensus on them at its summits. However, under Jokowi, ASEAN has gone from “the cornerstone” of Indonesian foreign policy to “a cornerstone”, in the words of his former top foreign affairs adviser, Rizal Sukma.[42] Indonesia’s approach to two crises following ASEAN meetings, one in 2012 under Yudhoyono and one in 2016 under Jokowi, illustrates the difference.

In 2012, ASEAN foreign ministers found it impossible to agree to a communiqué for the first time in the organisation’s history, because the Cambodian chair of the meeting would not agree to a statement critical of China’s actions in the South China Sea. Then Foreign Minister Natalegawa conducted 72 hours of shuttle diplomacy to ensure a compromise statement was issued shortly thereafter.[43]

However, during a similar crisis following a China–ASEAN ministerial meeting in Yuxi, China, in June 2016, there was no comparable Indonesian effort to build a consensus among ASEAN members.[44] In the days prior to the meeting, Southeast Asian ministers had agreed that Singapore, as ASEAN’s country coordinator for relations with China, would deliver a statement to the press at the conclusion of the meeting. Although only obliquely critical of Chinese actions, the statement would nevertheless have been a clear and unified indication of ASEAN’s concerns over Chinese behaviour in the South China Sea, just a month before an arbitral tribunal in The Hague was scheduled to deliver a verdict in the Philippines’ suit against China over that behaviour.

At the time, China was desperately seeking international support for its argument that the tribunal was without jurisdiction, and the case without merit. When Chinese officials learned that the statement was to be given, they put pressure on Cambodia, which has received billions of dollars in Chinese aid in recent years, to withdraw its approval of the statement. Cambodia did so, depriving ASEAN of a consensus and preventing the Singaporean foreign minister from delivering his critique to the press. (A Malaysian official inadvertently leaked it a few hours later.)

Unlike in 2012, there were no heroics from Natelagawa’s successor as Foreign Minister, Retno Marsudi. Although she had sought President Joko Widodo’s approval to play a similar role to that played by Natalegawa in the previous crisis, the president demurred, worried that such a high-profile Indonesian effort would anger China.[45] In the days that followed, Singapore sought to reconstruct the consensus that had existed a few days earlier, without success.[46] The case illustrated the other ASEAN states’ limited ability to forge consensus among members, and the significance of Indonesia’s absence from such efforts.

Since the Yuxi meeting in June 2016, there have been other indications that Jokowi is reluctant to criticise China in the context of regional diplomacy. For example, a month later, when Retno proposed a response by the foreign ministry to the ruling of the arbitral tribunal in the Philippines’ case against China, Jokowi originally struck any mention of UNCLOS from the statement. Only a later intervention with the president by Luhut, the coordinating minister for politics, law, and security and a close adviser to Jokowi, convinced Jokowi that the reference would not anger China and should be included.[47]

Retno finally gained approval for more active diplomacy later in July 2016, when she played a high-profile role in pushing her counterparts towards a consensus communiqué at the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Vientiane, Laos. The effort spared ASEAN further embarrassment.[48] In general, however, as China has increased its activity around the Natunas, Indonesia under Jokowi has responded by emphasising its military capabilities while resiling from the key diplomatic role in the broader South China Sea disputes that it played under Yudhoyono. In the South China Sea, Jokowi seems content for Indonesia to go it alone.

A high-water mark for Sino-Indonesian ties?

But Jakarta’s recent pattern of deference to Beijing — in investment, in its campaign against illegal fishing, and in regional diplomacy — could be upended by historical anxieties, communal tensions, challenges in executing infrastructure investments, or an escalation in the confrontations around the Natunas. An examination of these risks suggests that relations between the two may have reached their high- water mark under Jokowi.

Historical anxieties and communal tensions

Indonesian officials have historically regarded Beijing’s role in the region with great anxiety, dating back to the close relationship between the Chinese Communist Party and the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). According to the official Indonesian history of events, contested by some scholars but still widely accepted in Jakarta, the PKI attempted a coup with Chinese backing.[49] Relations between Jakarta and Beijing were not restored until 1990, long after most of Indonesia’s neighbours.[50]

The history of Indonesian politics is also replete with nationalist anxiety about the loyalty of the Chinese community. Chinese Indonesians have faced resentment for the community’s relative wealth and preferential treatment by the Dutch. Under Suharto, Chinese Indonesians were forced to assimilate and abandon aspects of their culture, and in the days before his fall, anti-Chinese riots hit communities around Indonesia. Since the return of democracy, Chinese Indonesians have prospered, and many have reconnected with Chinese culture. A smaller subset have “reoriented themselves” towards mainland China, and re-established business links with the mainland.[51]

These are typical activities for a diaspora community with cultural links overseas that should not in and of themselves raise questions about their allegiance. Still, some Indonesians harbour lingering suspicions about the loyalty of Chinese Indonesians, and are anxious about the community’s economic links with an increasingly powerful economy in the People’s Republic. Aware of this unease, many pluralist Indonesians — including those in Jokowi’s religious and political milieu — are reluctant to see a downturn in relations between the two countries for fear that it could agitate communal tensions, and upend hard-won ethnic harmony at home.

The tensions surrounding the February 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election make these concerns all the more acute. The province’s ethnic Chinese Christian governor, Basuki Tjahja Purnama, has been attacked on racial and religious grounds in the run-up to the election, with at least 50 000 protestors coming out into the streets in November 2016 to demand his arrest on specious charges of blasphemy.[52] If tensions were to boil over, or if Beijing were to intervene — rhetorically or otherwise — on the side of Chinese Indonesians in a way that Indonesians believe breaches norms of sovereignty, it might become more difficult for Jokowi to work with China or take its interests into account. Such an intervention is not implausible; in September 2015 the Chinese ambassador to Kuala Lumpur’s comments on Malaysian treatment of ethnic Chinese Malaysians amid similar tensions set off a firestorm of criticism.[53]

Challenges with Chinese investments

The increase in high-profile Chinese investments presents risks to the Sino-Indonesian relationship in two ways. First, many Indonesians are wary of the importation of foreign labour in general, and of Chinese labour in particular. There are fears that Chinese workers will flood Indonesia if it accepts Chinese investment, although in fact the number of Chinese workers at present is quite small.[54] (Chinese officials claim that the use of unskilled Chinese labour would be uneconomical, because importing Chinese labour would be more expensive.)[55]

The politics of the issue may nevertheless make Chinese investment less attractive to Jokowi. In August 2015, as the contest for the Jakarta–Bandung high-speed rail project gathered momentum, Indonesia’s leading news magazine, Tempo, published a cover story critical of the use of Chinese labour. Against an ominous red background, Tempo depicted Jokowi as a Chinese labourer, beside text reading “Welcome, Chinese Worker”.[56]

Second, Chinese infrastructure projects in Indonesia have acquired a reputation for low quality and late completion. Many Indonesian officials who worked on Chinese investments in the Yudhoyono administration cite the example of the Celukan Bawang power plant in Bali, which was completed years late and at a fraction of the promised capacity.[57]

Jokowi’s decision to award the high-speed rail project to the Chinese–Indonesian consortium is an opportunity for Chinese investors to demonstrate that they can deliver a project on time, on budget, at a high quality, and with few if any unskilled Chinese workers. If the project is a success, Indonesia is likely to turn increasingly to China for assistance in infrastructure investment. But if China runs foul of Indonesian sensitivities, then the project could sour Jokowi and his ministers on further Chinese investment. Likewise, Chinese investors may learn that the regulatory and governance challenges that tend to turn private sector investors away from big projects in Indonesia are more trouble than increased investment is worth, and pull back over time.

Escalation around the Natunas

Despite tense moments off Natuna Besar during the March 2016 confrontation between Indonesian and Chinese law enforcement vessels, Indonesia under Jokowi has not sought to penalise Beijing by throwing up roadblocks to investment, blowing up captured Chinese fishing vessels, or taking a stronger stand in regional diplomacy. Following the incident, Chinese Coast Guard behaviour around the Natunas has been relatively restrained. In the two incidents that followed, Chinese Coast Guard vessels did not attempt to intervene to prevent the arrests of Chinese fishermen by Indonesia. Since then, Fisheries Minister Susi Pudjiastuti has told reporters that Chinese fishing vessels have not been seen in the waters around the Natunas.

But as noted earlier, the presence of Chinese fishermen around the Natunas appears to be seasonal. Based on past patterns, they could return between March and July 2017. If they do, and an incident between Indonesian Navy or law enforcement vessels and the Chinese Coast Guard escalates to a point that leaves Indonesian casualties, it may be difficult for Jokowi to suppress anti-Chinese sentiment, and may require a response beyond the deployment of troops and equipment to Ranai.

If the Sino-Indonesian relationship does take a turn for the worse, it is unlikely to go very far in that direction. Indonesia’s traditional non-alignment and preference for maintaining a “dynamic equilibrium” will exercise a gravitational pull on Indonesian policy, keeping it from adopting too anti-Chinese a posture.

Conclusion

Indonesia under Jokowi can be expected to continue to take unilateral action to reinforce the Indonesian position in the Natunas, both through military deployments and an increase in state-directed economic activity. But Indonesia under Jokowi has not played an effective leadership role within ASEAN on the broader South China Sea issue for three reasons.

First, Indonesia’s non-alignment has long left it inherently sceptical of engaging on one side or the other in great power tensions. Second, Jokowi himself is sceptical of the merits of the abstract concepts at stake and the summit diplomacy required to protect them. Third, Jokowi wants to maintain good relations with China in order to ensure that efforts to attract greater Chinese investment in his infrastructure projects are protected. However, if attitudes towards Chinese investment change over time in response to poor performance, or if confrontations around the Natunas escalate, or communal tensions flare, it could weaken Jokowi’s interest in maintaining good relations with China.

Jokowi’s reluctance to authorise a stronger Indonesian leadership role on the issue may undermine Indonesian security. Indonesia has a long-term interest in a strong ASEAN, in a rules-based order that constrains the prerogatives of great powers in the region, and in the peace and stability supported by both. Indonesian leadership within ASEAN would give cover to smaller ASEAN countries to take a stand against Chinese aggression, making collective action among ASEAN states easier.

Without strong Indonesian leadership, however, ASEAN will continue to struggle to come to a consensus on the issue, and China will continue to take advantage of ASEAN disunity to pursue its ambitions in the South China Sea, with few diplomatic consequences. ASEAN consensus is not a panacea for the challenges of the South China Sea; but its absence makes their management more difficult. Indonesian reluctance to lead in ASEAN also undermines Indonesia’s interest in lowering regional tensions and preventing Southeast Asia from becoming a venue for great power competition, because without a strong and united ASEAN, the United States has felt compelled to take on more of a leadership role in pushing back against Chinese actions in the South China Sea.

Jokowi’s unilateral approach may have stabilised the situation around the Natunas for now. But in time, Indonesia will find any unilateral efforts to shore up its position in the Natunas will be overwhelmed by Chinese military and commercial capacities greater than their own, now located much closer to Indonesian waters than they once were. In the longer term, Indonesia is better off investing in diplomatic leadership.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the Lowy Institute’s Engaging Asia Project, which was established with the financial support of the Australian Government and funded this research, to Brittany Betteridge and Angela Han for research assistance, and to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on previous drafts.

Notes

[1] Associated Press, “Indonesia Detains Chinese Fishing Boat and Crew for Illegal Fishing”, South China Morning Post, 18 June 2016, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/1977143/indonesia-detains-chinese-fishing-boat-and-crew-illegal.

[2] Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying’s Remarks on Indonesian Navy Vessels Harassing and Shooting Chinese Fishing Boats and Fishermen, 19 June 2016, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/t1373402.shtml.

[3] Francis Chan and Wahyudi Soeriaatmadja, “Indonesia Defends Navy for Firing Warning Shots at Chinese Poachers in South China Sea”, The Straits Times, 20 June 2016, http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/indonesia-defends-navy-for-firing-warning-shots-at-chinese-poachers-in-south-china-sea.

[4] The meeting was formally considered a limited Cabinet meeting: Wahyudi Soeriaatmadja, “Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s Trip to South China Sea Islands a Message to Beijing, Says Minister”, The Straits Times, 23 June 2016, http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/indonesian-president-sails-to-south-china-sea-islands-in-message-to-beijing.

[5] See, for example, Alan Dupont, “Lessons in Chinese Pushback to Sino Aggression”, The Australian, 28 June 2016, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/opinion/lessons-in-indonesias-pushback-approach-to-sino-aggression/news-story/5bd02838bff8c64ef73100143e72ec8d; “Annoyed in Natuna”, The Economist, 2 July 2016, http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21701527-china-turns-would-be-peacemaker-yet-another-rival-annoyed-natuna.

[6] One of the most extensive surveys of the dashed line’s history and geography can be found in “Limits in the Seas No 143 — China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”, Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, US Department of State, 5 December 2014, http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/234936.pdf. Although the line has become well known as the nine-dashed line, the number of dashes is inconsistent in Chinese maps, using as few as eight or as many as ten. As a result, this Analysis refers to the line as ‘the dashed line’. See Euan Graham, “China’s New Map: Just Another Dash?”, The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 17 September 2013, http://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinas-new-map-just-another-dash/.

[7] The East Natuna Gas Field holds 26 trillion cubic feet of proven natural gas reserves, a large deposit, but its contents are considered expensive to extract due to their high carbon dioxide content. Indonesian officials have estimated that extraction would only be profitable if oil prices were to rise above $100/barrel, making it less coveted than it would otherwise be. See Raras Cahyafitri, “East Natuna Development Faces Possible Negotiation Delay”, The Jakarta Post, 27 November 2015, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/11/27/east-natuna-development-faces-possible-negotiation-delay.html.

[8] Marina Tsirbas, “What Does the Nine-Dash Line Actually Mean?”, The Diplomat, 2 June 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2016/06/what-does-the-nine-dash-line-actually-mean/.

[9] Douglas Johnson, “Drawn into the Fray: Indonesia’s Natuna Islands Meet China’s Long Gaze South”, Asian Affairs 42, No 3 (1994), 154–155.

[10] Indonesia, Note Verbale, No 480/POL-703/VII/10, New York, 8 July 2010, para 4, http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/idn_2010re_mys_vnm_e.pdf.

[11] Klaus Heinrich Raditio, “Indonesia ‘Speaks Chinese’ in South China Sea”, The Jakarta Post, 18 July 2016, http://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2016/07/18/indonesia-speaks-chinese-in-south-china-sea.html.

[12] On the workshops, see Hasjim Djalal, Preventative Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: Lessons Learned (Jakarta: Habibie Center, 2003).

[13] The workshops did provide for the development of the principles later put forward as the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, which some argue has served a useful tension management function in the disputes. Scepticism regarding Indonesia’s ‘honest broker’ role should not be construed as a criticism of Indonesia’s efforts or abilities in these negotiations, which under Ali Alatas, Hasjim Djalal, Marty Natalegawa and others have been persistent, patient, and creative. Rather, it is a function of China’s efforts to block progress in most areas. See Bill Hayton, The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia (New Haven: Yale, 2014), 256–259.

[14] For the 2010 incident, see “Territorial Disputes in South China Sea on the Increase as China Flexes Muscles”, Mainichi Shimbun, 2 August 2010, http://web.archive.org/web/20100806005509/http://mdn.mainichi.jp/mdnnews/international/news/20100802p2a00m0na021000c.html. For the 2013 incident, see Scott Bentley, “Mapping the Nine-Dash Line: Recent Incidents Involving Indonesia in the South China Sea”, The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 29 October 2013, http://www.aspistrategist.org.au/mapping-the-nine-dash-line-recent-incidents-involving-indonesia-in-the-south-china-sea/. There may have been further incidents; the 2013 incident only came to light because the captain of the Indonesian vessel wrote up the encounter on a military blog accessed by Bentley. Jakarta has sought to play down such incidents lest it damage the perception that Indonesia is a neutral party in the broader South China Sea disputes, as Ristian Atriandi Supriyanto has argued: see “Indonesia’s South China Sea Dilemma: Between Neutrality and Self-Interest”, RSIS Commentaries No 126/2012, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/CO12126.pdf.

[15] Ristian A Supriyanto, Shahriman Lockman and Koh Swee Lean Collin, “China’s Rift with Indonesia in the Natunas: Harbinger of Worse to Come?”, The Diplomat, 25 March 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2016/03/chinas-rift-with-indonesia-in-the-natunas-harbinger-of-worse-to-come/. For the timeline of the incident, see Fiki Ariyanti, “Kronologi Kapal Maling Ikan Asal Tiongkok Dilumpuhkan di Natuna [Chronology of the Illegal Fishing Boat from China Taken Out in Natuna]”, Liputan 6, http://bisnis.liputan6.com/read/2463504/kronologi-kapal-maling-ikan-asal-tiongkok-dilumpuhkan-di-natuna.

[16] Chris Brummitt, “Frantic Phone Call Failed to Halt China-Indonesia Sea Spat”, Bloomberg, 23 March 2016, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-22/frantic-phone-call-failed-to-contain-china-indonesia-sea-spat. Interviews with Indonesian officials, April 2016.

[17] Chris Brummitt, “Indonesia Will Defend South China Sea Territory with F-16 Fighter Jets”, Bloomberg, 1 April 2016, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-31/indonesia-to-deploy-f-16s-to-guard-its-south-china-sea-territory.

[18] Brummitt, “Frantic Phone Call Failed to Halt China-Indonesia Sea Spat”.

[19] “Menkopolhukam Ingin Tingkatkan Kekuatan TNI AL di Natuna [Coordinating Minister for Politics, Law, and Security Wants to Raise the Strength of the Navy in Natuna]”, Antara, 22 March 2016, http://www.antaranews.com/berita/551439/menkopolhukam-ingin-tingkatkan-kekuatan-tni-al-di-natuna.

[20] Yohannes Paskalis, “Luhut: Indonesia, China to Step Up Security Partnership”, Tempo, 29 April 2016, http://en.tempo.co/read/news/2016/04/29/055767157/Luhut-Indonesia-China-to-Step-Up-Strategic-Security-Partnership.

[21] Under Article 111 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, coastal states may pursue and arrest vessels on the high seas if they are in ‘hot pursuit’ of the vessel for an act committed in its territorial waters or exclusive economic zone.

[22] Abba Gabrillin, “Koarmabar Sergap Kapal Nelayan China di Perairan Natuna [Western Fleet Command Ambushes Chinese Fishing Boat in Natuna Waters”, 28 May 2016, Kompas, http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2016/05/28/20234741/koarmabar.sergap.kapal.nelayan.china.di.perairan.natuna.

[23] Fadli, “Jokowi to Strengthen Border Areas”, The Jakarta Post, 7 October 2016, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/10/07/jokowi-strengthen-border-areas.html.

[24] Nick Wadhams and Bill Faries, “Blowing Up Boats Sets Indonesia’s Scarce Fish Swimming Again”, Bloomberg, 19 September 2016, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-09-18/blowing-up-boats-sets-indonesia-s-scarce-fish-swimming-again.

[25] Vida Macikenaite, “The Implications of China’s Fisheries Industry Regulation and Development for the South China Sea Dispute”, in The Quandaries of China’s Domestic and Foreign Development Dominik Mierzejewski ed (Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, 2014), http://dspace.uni.lodz.pl:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11089/11270/15.216_236_macikenaite.pdf.

[26] Marty Natalegawa, “Annual Press Statement of the Foreign Minister of the Republic of Indonesia”, Jakarta, 7 January 2011, http://indonesia.gr/speech-of-the-minister-of-foreign-affairsannual-press-statement-of-the-foreign-minister-of-the-republic-of-indonesia-dr-r-m-marty-m-natalegawa/.

[27] Interview with Indonesian official, Sydney, November 2016.

[28] Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, “Inaugural Address”, Jakarta, 20 October 2009, http://jakartaglobe.id/archive/sbys-inaugural-speech-the-text/. Yudhoyono’s wording varied between “a thousand friends and zero enemies” and “a million friends and zero enemies”. For further discussion of Jokowi’s politics and his worldview, see Aaron L Connelly, “Sovereignty and the Sea: President Joko Widodo’s Foreign Policy Challenges”, Contemporary Southeast Asia 37, No 1 (April 2015), 1–28.

[29] For examples of criticism of this nature, see Tri Wahono, “Politik Pencitraan SBY Gagal [SBY’s Image Politics Fail]”, Kompas, 24 April 2011, http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2011/04/24/15412766/Politik.Pencitraan.SBY.Gagal; and “SBY’s Foreign Policies ‘Failing his People’”, The Jakarta Post, 13 October 2014, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/10/13/sby-s-foreign-policies-failing-his-people.html. Yudhoyono did order the executions of some of those sentenced to death in 2013, following criticism that there had been no executions during the previous five years.

[30] For example, Jokowi departed early from an ASEAN Summit in Langkawi, Malaysia, in April 2015, and only reluctantly agreed to attend the G20 in Brisbane in November 2014, the APEC Summit in Manila in November 2015, and the Special US–ASEAN Summit in Sunnylands in February 2016. (For the ASEAN Summit, see Tama Salim and Ina Parlina, “Jokowi to Skip APEC Summit”, The Jakarta Post, 12 November 2015, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/11/12/jokowi-skip-apec-summit.html; Information on G20 Summit based on interviews with Indonesian diplomats, Sydney, October 2014; information on Sunnylands based on interview with business figure, Washington, December 2015.) While Jokowi is uninterested in summitry, he does want Indonesia to be seen as an important country with a seat at the big tables, as Greg Fealy and Hugh White have noted (see “Indonesia’s ‘Great Power’ Aspirations: A Critical View”, Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 3, No 1 (2016), 92–100). For example, as Fealy and White note, at the APEC Summit in Beijing in November 2014, Jokowi insisted that he sit near Chinese President Xi Jinping, US President Barack Obama, and Russian President Vladimir Putin at dinner, rather than at his assigned seat at the margins. Indonesia has also launched a bid for a term on the UN Security Council under Jokowi: “Indonesia Eyes Seat on the UN Security Council”, The Jakarta Post, 30 September 2015, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/09/30/indonesia-eyes-seat-un-security-council.html. However, while these suggest that Jokowi cares that Indonesia is accorded the respect of its peers, they should not be seen as indications that Jokowi is concerned with the substance of such summits, or abstract concepts discussed at them such as the shape of regional architecture or international law.

[31] Darmansjah Djumala, “Ketika Diplomasi Membumi [When Diplomacy Comes Down to Earth]”, Kompas, 15 November 2015, http://internasional.kompas.com/read/2014/11/15/05320031/Ketika.Diplomasi.Membumi.

[32] Bappenas, “Medium Term Development Plan: RPJMN 2015–2019”, 9 March 2015.

[33] 2015 Indonesia Investment Climate Statement, US Department of State, http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/241809.pdf.

[34] Interviews with advisers to Jokowi, Jakarta, January and April 2016.

[35] Chris Brummitt, “Desperate for Investment, Indonesia Plays China vs Japan”, Bloomberg, 20 May 2015, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-05-19/desperate-for-investment-indonesia-plays-china-vs-japan.

[36] Though the Chinese bid did not require a guarantee in the Indonesian budget, the Indonesian Government will ultimately be liable for the project if it fails, because the Indonesian firms involved in the consortium are all state-owned enterprises. Jokowi’s concern seems to have been that the project not be carried on the budget’s ledgers, counting against the budget deficit, which must remain under 3 per cent under Indonesian law. For more on the high speed rail project, see Wilmar Salim and Siwage Dharma Negara, “Why is the High-Speed Rail Project so Important to Indonesia?”, ISEAS Perspective, Issue 2016, No 16 (7 April 2016), https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2016_16.pdf.

[37] Saiful Mujani Research and Consulting, “Kinerja Presiden Jokowi: Evaluasi Publik Nasional Setahun Terpilih Menjadi Presiden”, slides 19–20, 9 July 2015, http://www.slideshare.net/saidimanahmad/print-setahun-jokowi-rev.

[38] Interviews with Indonesian officials, Jakarta, March 2015. For more on the vessel in question, see Tama Salim, “Susi Continues Legal Fight against Hai Fa”, The Jakarta Post, 15 June 2015, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/06/20/susi-continues-legal-fight-against-hai-fa.html. The vessel was impounded, but five months later departed without authorisation and sailed back to China. Fisheries Minister Susi Pudjiastuti has also raised questions about the Navy’s willingness to participate in enforcement of fisheries laws, publicly chiding the Navy for failing to capture Chinese vessels and privately telling colleagues that she believes Navy officials had received bribes from Chinese fishing interests to allow their vessels to fish illegally in Indonesian waters: see Nani Afrida, “Susi Torpedoes Navy over Chinese Vessel”, The Jakarta Post, 26 February 2016, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/02/26/susi-torpedoes-navy-over-chinese-vessel.html; Interview with Indonesian official, March 2015.

[39] Tama Salim, “RI Flexes Muscle, Sinks Chinese Boat, A Big One”, The Jakarta Post, 20 May 2015, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/05/20/ri-flexes-muscle-sinks-chinese-boat-a-big-one.html.

[40] Trefor Moss, “Indonesia Blows Up 23 Foreign Fishing Boats to Send a Message”, Wall Street Journal, 5 April 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/indonesia-blows-up-23-foreign-fishing-boats-to-send-a-message-1459852007.

[41] Interview with Indonesian diplomats, Sydney, August 2016.

[42] Prashanth Parameswaran, “Is Indonesia Turning Away from ASEAN Under Jokowi?”, The Diplomat, 18 December 2014, http://thediplomat.com/2014/12/is-indonesia-turning-away-from-asean-under-jokowi/.

[43] Donald K Emmerson, “Beyond the Six Points: How Far will Indonesia Go?”, East Asia Forum, 29 July 2012, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2012/07/29/beyond-the-six-points-how-far-will-indonesia-go/.

[44] Interviews with Indonesian, Singaporean, Malaysian, and Australian diplomats, Sydney and Canberra, June 2015. At a later summit, Indonesia did begin to demonstrate some leadership on the issue, with Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi convening a side meeting “as a good faith measure to remind all members of ASEAN’s norms and values”. See Ben Otto, “ASEAN Looks for Wiggle Room to Skirt South China Sea Impasse”, Wall Street Journal, 24 July 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/asean-looks-for-wiggle-room-to-skirt-south-china-sea-impasse-1469342955.

[45] Interview, Indonesian official, Jakarta, July 2016.

[46] Interview with Singaporean diplomats, August 2016.

[47] Interviews with Indonesian officials, July 2016.

[48] Tama Salim, “Indonesia’s Tactful Diplomacy Key to Uniting ASEAN”, The Jakarta Post, 27 July 2016, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/07/27/indonesia-s-tactful-diplomacy-key-uniting-asean.html.

[49] John Roosa, Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup D’Etat in Indonesia (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006).

[50] Rizal Sukma, Indonesia and China: The Politics of a Troubled Relationship (London: Routledge, 1999).

[51] Setijadi, “Ethnic Chinese in Contemporary Indonesia”.

[52] Jewel Topsfield, “Violence in Jakarta as Muslims Protest, Demand Christian Governor Ahok be Jailed”, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 November 2016, http://www.smh.com.au/world/jakarta-protest-thousands-of-muslims-gather-to-demand-jailing-of-christian-governor-ahok-20161104-gsifnm.html.

[53] Prashanth Parameswaran, “The Truth About China’s ‘Interference’ in Malaysia’s Politics”, The Diplomat, 2 October 2015, http://thediplomat.com/2015/10/the-truth-about-chinas-interference-in-malaysias-politics/.

[54] Although there are rumours of over 10 million Chinese workers in Indonesia, the Manpower Ministry suggests there have only been 14 000 to 16 000 in any one-year period: “Illegal Foreign Workers, Rule Breakers Face Immediate Deportation: Manpower Minister”, Manpower Ministry, 26 July 2016, http://www.thejakartapost.com/longform/2016/07/26/illegal-foreign-workers-rule-breakers-face-immediate-deportation-manpower-minister.html. Undocumented Chinese immigrants are not a major problem either: only five examples of undocumented Chinese labour have appeared in the Indonesian press since 2011, at two factories in Banten, at a bauxite smelter in West Kalimantan, at a power plant in Bali, and on the high-speed rail line.

[55] Anton Hermansyah, “China Shrugs Off Labor Influx into RI”, The Jakarta Post, 2 May 2016, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/05/02/china-shrugs-off-labor-influx-into-ri.html.

[56] “Selamat Datang Buruh Cina [Welcome, Chinese Worker]”, Tempo, 31 August 2015.

[57] Alit Kertaraharja, “Celukan Bawang Power Plant to Boost Bali’s Electricity Supply”, The Jakarta Post, 14 August 2015, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/08/14/celukan-bawang-power-plant-boost-bali-s-electricity-supply.html.