The price of Indonesia’s economic nationalism

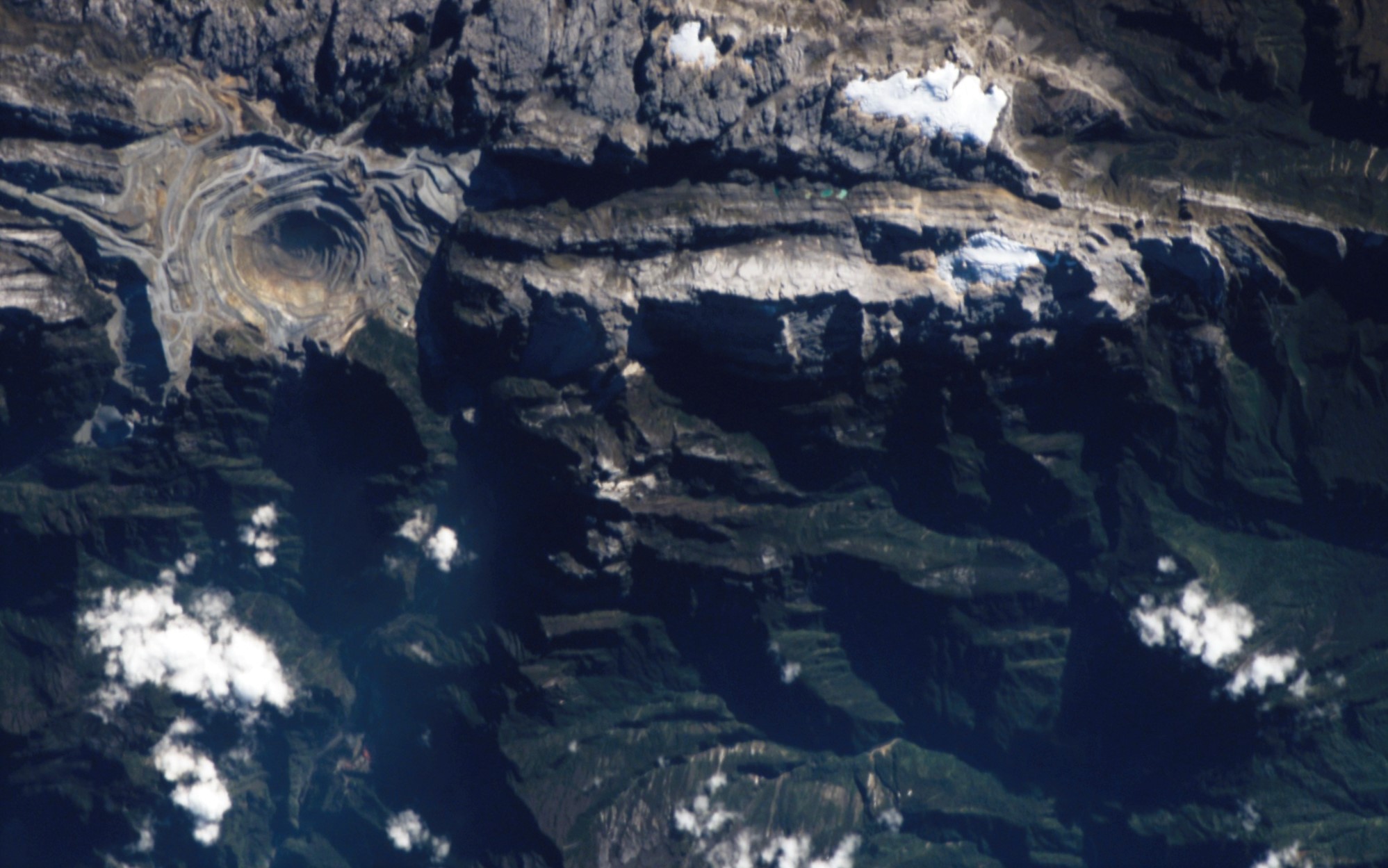

Jakarta's efforts to retake control of the country's natural resources are going to be costly for taxpayers, wrote Matthew Busch for the Wall Street Journal on 15 March (Photo: Flickr/Nasa)

Indonesia's largest mining investor may soon be pulling out of the country. Faced with a new regulation requiring majority divestment of its local subsidiary, US mining company Freeport McMoran has signaled its intent to pursue international arbitration should negotiations remain at an impasse past June. If filed, such a claim would be among the largest in history and have a chilling effect on other investors doing business in Southeast Asia's largest economy.

At issue is Freeport's operations at Grasberg, the world's largest gold mine. Jakarta wants higher royalties, land relinquishments, more materials procured from local suppliers, the construction of a $2 billion smelter and, crucially, a 51% divestment of the Arizona-based company's stake in its local subsidiary.

It's all part of Indonesia's larger effort to exercise greater control over its natural resources. In the oil-and-gas sector, President Joko Widodo overruled plans previously approved for an offshore LNG project, deciding instead that the project should be built in a remote and underdeveloped part of eastern Indonesia to create a 'multiplier effect' for local communities. Never mind that Mr Widodo's then energy minister opposed the move and pointed to an independent costing that found this would be 30% more expensive than the offshore project.

In the minerals sector, officials imposed bans on the export of nickel and bauxite to force miners to build industrial facilities locally. The ban was later reversed after it was discovered that local and state-owned miners were also being hurt by the policy.

Meanwhile, over the course of five years of negotiations Freeport has acceded to most of Jakarta's ever-shifting demands in a series of interim agreements. In return, the company has sought to preserve its protections (including recourse to international arbitration) and extend the security of its investments beyond the end of its original contract in 2021. But it has refused to concede on the 51% divestment, and on this point Jakarta, too, seems unwilling to budge.

The standoff reflects a growing assertiveness toward Freeport among Indonesia's elites. Many bitterly recall how the mining company's contract in the early 1990s also mandated a divestment of up to 51%, only for the company to escape the clause at the last minute through a favorable change in legislation by the Suharto government.

Senior officials now seem eager to take up the fight with Freeport again for the 51% stake, despite protests that the divestment would affect Indonesia's investment climate, that Grasberg already contributes $16 billion to state revenues, or that the minerals at the mine might as well have been, in the words of an early explorer, 'on the moon' had it not been for Freeport's technical innovation and appetite for risk. In fact, Indonesia's energy minister has explained that the divestment requirement was inserted at the specific guidance of Mr Widodo.

Given Freeport's willingness to concede on almost all of Jakarta's demands if only it could preserve its rights to Grasberg, Jakarta could have simply kept negotiating higher payments from the company. That would have been the smart play, if protecting citizens' interests was the point.

The Lowy Institute acknowledges the support of the Victorian Government Department of Premier and Cabinet for Matthew's position.