Private and community sector initiatives in refugee employment and entrepreneurship

This working paper examines two areas for achieving positive settlement outcomes for refugees and in generating refugee employment in Australia and internationally: refugee entrepreneurship and public-private sector partnerships in employment creation for refugees.

Abstract

In recent years refugee intakes to Australia and other countries have increased dramatically. Australia has taken in 12 000 refugees from the Syrian conflict in addition to the (increasing) annual humanitarian intake. Refugees face substantial barriers engaging with the economy and labour market. One option open to refugees is to create their own job by starting a business. This working paper explores the experiences of refugee entrepreneurs in Australia and reviews the policies and programs designed to assist refugee entrepreneurs in Australia and other countries. Most refugees, however, will not become entrepreneurs. Their challenge is to find a job. Public and private sector partnerships have great potential in developing innovative solutions to employment creation for refugees. This paper reviews Australian and international research and policy development in these two areas and argues that innovative solutions via private and community sector partnerships in employment creation and enterprise start-ups for refugees are critical.

Introduction

In the past few years the world has witnessed unprecedented flows of displaced people. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) we are witnessing the highest levels of displacement on record: 65.6 million people around the world have been forced from their home, among them almost 22.5 million refugees over half of whom are under the age of 18.[1] The UNHCR estimates that nearly 34 000 people are forcibly displaced every day because of conflict or persecution. During the second half of 2015, more than one million people arrived in Europe by sea, a more than fourfold increase compared to the previous year’s 216 000 arrivals.[2] As the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recently reported, “warfare and instability in the Middle East and Africa, with countries in the Mediterranean area under particular pressure” has put humanitarian immigration flows at the top of the global immigration agenda and “is also causing countries to review the ways in which their humanitarian programmes and procedures are working”.[3]

This is certainly the case in Australia, which has a relatively generous humanitarian and refugee immigration program of around 13 700 per year in recent years. Australia’s resettlement program is the third highest in the world and the highest per capita, although Australia received just 0.24 per cent of the world’s asylum claims in 2014.[4] On 9 September 2015, the then Prime Minister Tony Abbott announced that Australia would permanently resettle 12 000 refugees from the Syria-Iraq conflict in addition to the planned annual intake of refugees and humanitarian immigrants. Since then the Australian Government has announced an increase in Australia’s humanitarian intake to 16 250 in 2017–18 and 18 750 in 2018–19 while the Opposition plans to increase the humanitarian intake to 25 000 by 2024–25.[5]

In Australia, like many other Western nations, issues of refugee intake and settlement are controversial.[6] Australia receives around 200 000 permanent immigrant arrivals and over 700 000 temporary immigrant arrivals each year.[7] Comparatively, the humanitarian program is 12 per cent of the permanent program intake. Despite this, the refugee program seems to dominate public debate and discourse on Australian immigration policy.[8]

In the Immigration Outlook 2017 report, the OECD argued that the “peak of the humanitarian refugee crisis is behind us … It is now time to focus on how to help people settle in their new host countries and integrate into their labour markets. This demands rethinking both domestic policies and international co-operation … improving the integration outcomes of immigrants and their children, including refugees, is vital to delivering a more prosperous, inclusive future for all.”[9]

This working paper examines refugee settlement and integration in Australia, in particular the importance of employment to successful refugee settlement. Finding a job is a necessary, though not sufficient, part of any successful refugee settlement strategy.[10] Yet the research also confirms that refugees have great difficulty in finding a job. At the G20 meeting in 2016, employment ministers noted that “employment plays a key role in promoting the sustainable integration of over 130 million regular migrants, approximately 5 million refugees and significant numbers of returning migrants in the G20”.[11] The historic 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants led to the development of the UN Global Compacts on Refugees and on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, which have the potential to drive the critical question of refugee and migrant integration more centrally into the international policy arena.[12]

It is timely then to focus on two areas of considerable potential in achieving positive settlement outcomes for refugees and in generating refugee employment in Australia and internationally: refugee entrepreneurship and public-private sector partnerships in employment creation for refugees. This paper reviews Australian and international research and policy development in these two areas. It argues that innovative solutions related to refugee entrepreneurship and private and community sector partnerships in employment creation for refugees are critical.

Immigrant and refugee entrepreneurship

There is a strong international literature on immigrant entrepreneurship.[13] Immigrant entrepreneurs not only create their own jobs, they also generate employment for others, including other immigrants. The OECD has estimated that a foreign-born entrepreneur in a small firm creates on average between 1.4 and 2.1 additional jobs.[14] In the United Kingdom immigrant entrepreneurs — whose rate of entrepreneurship is nearly double that of UK-born individuals — are responsible for 14 per cent of jobs created in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).[15] Immigrant entrepreneurs also support the integration of new immigrants and reduce their social exclusion.[16] Researchers at the University of Birmingham argue that in Britain new migrant firms “act as buffers against unemployment and social exclusion in disadvantaged communities, and as vehicles for the social integration of disparate migrant populations both with one another and into the British mainstream. As employment providers, they offer fellow migrants a haven from an often hostile job market, while social integration is fostered by the interaction of migrant shopkeepers and their workers with their customers.”[17] Research in Australia has demonstrated that immigrant entrepreneurs have a positive impact on the social and built environment of the new neighbourhoods into which they settle.[18]

However, in contrast to the research and policy development related to immigrant entrepreneurship there has been very little international research into refugee entrepreneurship.[19] Researchers at the Refugee Studies Centre at the University of Oxford see refugee entrepreneurship as a form of ‘bottom-up innovation’,[20] a critical but overlooked component of a broader phenomenon called ‘humanitarian innovation’.[21] One study of Congolese, Somali, and Rwandan refugees in Uganda found that 60 per cent were self-employed, and played an important role in creating employment for others, including Ugandans: 40 per cent of those employed by refugee entrepreneurs in urban areas were Ugandan.[22] Another study of refugee entrepreneurship in the United Kingdom pointed to the fact that ‘joblessness’ among refugees in the United Kingdom is the highest of any immigrant group.[23] Other studies from the United Kingdom and Belgium have emphasised that humanitarian immigrants consider setting up a business as an opportunity to ‘integrate’ in the community.[24] Canada received just over 40 000 Syrian refugees between November 2015 and January 2017. Many of these Syrian refugees had owned and operated a business in Syria, and turned to entrepreneurship after settling in Canada.[25]

There is a strong connection between entrepreneurship and development. Access to entrepreneurship opportunities (particularly in the informal sector of the economy) is perhaps the most critical factor in successful rural to urban migration in countries such as Africa and India.[26] Diasporic entrepreneurship is an important link between migration and economic development in developing nations. As one recent report argued: “Encouraging members of the diaspora to pursue entrepreneurial ventures seems a matter of common sense as an element of development policy.”[27] Similarly, diasporic entrepreneurship is also critical for successful international immigrant mobility to, and settlement in, Western countries. A study of Somali community businesses in the United Kingdom found that they are dependent on their social networks, particularly because their businesses are less formalised and located in underprivileged areas, almost always catering to other Somali members. But at the same time UK research suggests that since many humanitarian immigrant businesses operate as ‘small’ enterprises and are usually reliant on cash transactions and ‘informality’, they lose out on support from more formalised business structures.[28]

Studies in the United States on refugee entrepreneurship have examined the impact of refugee entrepreneurship on the local economy, concluding that refugee businesses have significant economic ripple effects throughout the local economy.[29] Other studies looked at the characteristics and factors that affect refugee entrepreneurship,[30] while others concentrated on the characteristics of refugees[31] and their businesses.[32] One study found that in the local economy of Portland, Maine, refugee women are over-represented as entrepreneurs.[33]

Refugees in the Australian labour market

Humanitarian migrants have greater problems with settlement compared to other categories of Australia’s immigrant intake. They also experience greater socio-economic disadvantage in Australia than other immigrants.[34] Refugees face problems in the areas of housing, employment, and health as well as with social connections in Australia.[35] Humanitarian immigrants experience more problems in the labour market than other immigrants. In 2006 the unemployment rate for those born in Somalia was 30.7 per cent and Sudan 28.2 per cent at a time when the average Australian unemployment rate was below 6 per cent.[36] When they do get jobs, humanitarian immigrants face ‘occupational skidding’;[37] that is, they do not get jobs commensurate with their qualifications and generally end up working in low-skill and low-paid occupations irrespective of their human capital.[38] Thus, some humanitarian arrivals are trapped in low-income jobs in secondary labour market niches or remain economically excluded as part of a social underclass.

The humanitarian program is the most controversial aspect of Australian immigration. Refugees are the most disadvantaged cohort of immigrant arrivals and face the greatest settlement difficulties in Australia. Recent data suggest that “after 18 months in Australia, only 17 per cent of humanitarian migrants are in paid work”.[39] For refugee women, the employment problem is even more difficult with refugee women four times more likely than refugee men to be unemployed 18 months after settlement in Australia. This gender dimension of the refugee employment problem is vividly demonstrated by the labour force participation rates: 20 per cent for refugee women compared to 60 per cent for refugee men.[40]

A 2017 report on employment and settlement services for refugees, drawing on insights from experts and policymakers from Australia, Canada, the United States and Germany, stressed the importance of employment to successful refugee settlement: “If there is a weak link in Australia’s settlement record, it is getting refugees into jobs soon after they arrive. There is overwhelming evidence that employment provides the bedrock for successful settlement. The best way to help humanitarian migrants to build flourishing lives is to help them find work.”[41]

The current expansion of Australia’s humanitarian program, in addition to the one-off Syrian-conflict refugee intake, puts pressure on refugee employment: the refugee intake in 2016–17 will be nearly double that of previous years. As the Centre for Policy Development (CPD) argues, this increased intake comes at a time of profound changes in the economy that mean many of the jobs taken up by refugees in the past are becoming scarcer. The areas where new jobs are created in Australia today are in highly skilled and qualified jobs. Because of a lack of high levels of education and qualifications — or lack or recognition of these qualifications and lack of employment experience in Australia — refugees seek employment in low-skilled jobs. However, these jobs are diminishing in the Australia labour market, with the number of low-skilled labouring jobs in Australia expected to decrease by 15 400 from 2017 to 2020.[42]

The CPD report “Settling Better: Reforming Refugee Employment and Settlement” identifies five principal barriers to newly arrived refugees finding jobs: limited English, a lack of work experience, poor health, a lack of opportunities for women, and having only been in Australia for a short time.[43] The report also identifies successful integration strategies across Europe and North America, including “the provision of early assistance, skills assessment and recognition, labour market support programs, measures to boost social capital, coordination across jurisdictions and public-private partnerships”.[44]

However, one area of considerable potential in generating refugee employment in Australia and internationally that is not considered in the CPD report relates to refugee entrepreneurship. This has two dimensions: first, the movement of refugees to private entrepreneurship, to establishing or taking over (usually a micro or small) business. The second is the role of social enterprises run by refugees and others in generating refugee employment opportunities. This is perhaps the largest gap in the research, literature and policy development related to refugee employment and settlement.

Refugee entrepreneurship in Australia

One pathway to increase refugee employment, reduce socio-economic disadvantage, and generate more successful settlement outcomes in refugee communities is the establishment of private business enterprises that are owned and/or controlled by refugees. Some of Australia’s most successful businesses were started by humanitarian immigrants.[45] However, most humanitarian immigrants, like most immigrants who become entrepreneurs in Australia, establish small and medium-sized enterprises.

While some entrepreneurship literature is interested in identifying the personality traits of stellar business innovators such as Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg, the literature of immigrant entrepreneurship — pioneered by US Sociologist Ivan Light[46] — takes a very loose definition of entrepreneurship as those who are employers or self-employed. In the Australian context, this can be defined as a person who has an ABN. This is the definition applied in this report.

In a 1995 survey of 349 immigrant entrepreneurs in Sydney, Perth, and Melbourne, 87 or 25 per cent entered as humanitarian immigrants.[47] Another study found that one-fifth (21 per cent) of humanitarian immigrants received their main income from their own business.[48] This proportion was significantly higher than for any other migrant category. At the 2006 Census, 15.9 per cent of Australian-born citizens were entrepreneurs while birthplace groups with a high number of recently arrived humanitarian immigrants had an average rate of entrepreneurship of 18.8 per cent for the first generation and 15.1 per cent for the second generation.[49] This second-generation figure is surprisingly high because the rate of entrepreneurship normally falls off dramatically between first- and second-generation immigrants.[50] Some humanitarian immigrant groups in particular have very high rates of entrepreneurship, particularly first-generation immigrants born in Iran (23.9 per cent), Iraq (21.9 per cent), and Somalia (25.5 per cent) and second-generation immigrants with parents born in the Congo (17.4 per cent) and Sudan (16.7 per cent).[51] While the rate of entrepreneurship is higher for humanitarian immigrant men than women, as for all immigrants,[52] many female humanitarian immigrants also move to entrepreneurship, although little is known about female humanitarian immigrant entrepreneurs in Australia.

This section looks at the barriers to refugee entrepreneurship. It presents ABS data that shows that humanitarian entrants are more likely to become entrepreneurs than other visa categories of immigrant arrivals. It also explores new research into Hazara refugee entrepreneurs in Adelaide and the refugee entrepreneur paradox.

Barriers

While refugees face perhaps the greatest barriers to entrepreneurship of any immigrant group they have the highest rates of entrepreneurship of any immigrant group. This is the entrepreneur’s paradox.

All entrepreneurs require start-up capital, money to establish the business. There is a long tradition of immigrant entrepreneurship in Australia, particularly related to immigrant minorities for whom English is not their first language. As the history of Greek, Italian, Lebanese, Chinese, and Korean immigrant entrepreneurship shows, immigrants raise this financial capital out of the savings from their employment or by drawing on family and community networks (social capital) for loans.[53]

Refugees, however, arrive with no financial capital. For boat people, savings are depleted on the costs associated with the journey to Australian shores, including payment to people smugglers. For humanitarian arrivals, years spent in refugee camps before being selected as part of Australia’s annual humanitarian intake means that most arrive in Australia with no savings. To make matters worse, most refugees find it hard to get employment and spend a long time — many years in some cases — unemployed. This is in contrast to their Greek and Italian counterparts many decades earlier who arrived at times of full employment when a booming manufacturing sector meant that they could walk off the boat one day and find a factory job — or jobs — the next day. Multiple jobs are difficult to find in the contemporary Australian labour market, which has among the world’s highest casualisation rates, with close to 2.4 million casual employees, or 20.1 per cent of the workforce in 2016.[54] This means that the task of accumulating sufficient savings is difficult and takes some time. Refugees also lack credit histories or secure and sustained employment and do not possess assets against which a business loan could be secured, meaning they cannot access bank finance to start up their business.

Moreover, newly arrived refugees usually come to Australia after many years of displacement from their home country and often they are fleeing violence, conflict, persecution, and discrimination. Their family networks are fractured in the process of displacement and flight. In the case of boat people many young men are sent alone — financed by the extended family’s meagre resources. This means that they lack social capital once they arrive in Australia: their network of family and friends are small, particularly compared to the chain migration of Greeks and Italians who often arrived to be met by very large and established family and village community networks in Australia. Since immigrant entrepreneurship is embedded in family and ethnic community networks, a lack of a social network is also a strong barrier to entrepreneurship for newly arrived refugees.[55]

Many immigrant businesses are sustained by supplying goods and services to the co-ethnic community in neighbourhoods where they settle. These ethnic niche businesses have the comparative advantage of a local market that want service in their home tongue and/or are seeking familiar goods or products for traditional cuisine or fashion. For refugee communities, it sometimes takes decades before the local community in Australia is large enough to sustain an ethnic niche business. Moreover, whereas immigrant entrepreneurs can draw on diasporic social networks back home or in other countries for loans and business support, for refugees the diaspora is fractured and often located in refugee camps and therefore unable to assist.

The other barrier that intending refugee entrepreneurs in Australia face is a lack of strong English language fluency; that is, they lack the linguistic capital that is necessary for a non-ethnic niche business in Australia. While all humanitarian entrants receive English language training on arrival in Australia, it often takes many years to reach a level of fluency required for business. At the same time, newly arrived refugees are not familiar with local rules and regulations that constrain and shape enterprise development in Australia. They often come from countries in the Middle East, Africa, or Asia where the business sector is much less regulated and where the informal business sector is the norm. This lack of knowledge of local business regulations is a barrier to enterprise set-up in Australia for refugees.

The data: Humanitarian migrants are more likely to become entrepreneurs

Despite these barriers — which non-refugees do not face to the same degree — refugees demonstrate a higher rate of entrepreneurship than other immigrants in Australia. According to figures released for the first time by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in 2015: “Humanitarian migrants were the most entrepreneurial while skilled migrants generated the most income in 2009–2010.”[56] The ABS calibrated personal income data for migrants for the 2009–10 financial year from the Personal Income Tax and Migrants Integrated Dataset (PITMID) and compared refugees with other immigrant visa categories. The data shows that “while almost two-thirds of migrant taxpayers were migrants with a Skilled visa — reporting $26 billion in Employee income — Humanitarian migrants displayed greater entrepreneurial qualities and reported a higher proportion of income from their own unincorporated businesses and this income increased sharply after five years of residency”.[57]

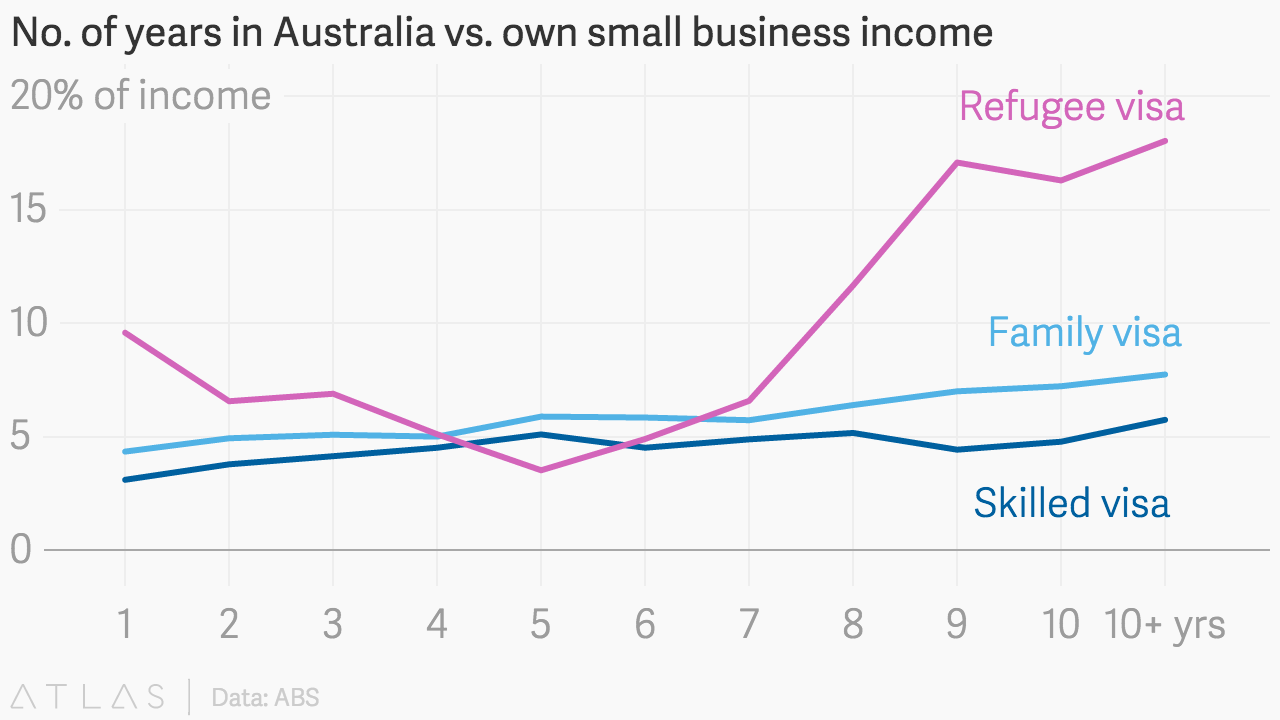

Figure 1 shows that migrants who arrived under a refugee visa had a rate of entrepreneurship of 9.3 per cent, nearly double that for migrants who arrived under a family visa (5.7 per cent) and more than double that for migrants who arrived under a skilled visa (4.3 per cent).

Figure 1: Rates of entrepreneurship of refugees and other migrant classes

Source: Nikhil Sonnad, “Refugees the Most Enterprising in Australia”, Quartz, 8 September 2015, https://qz.com/1152397/photos-of-the-two-ancient-tombs-just-been-opened-in-luxor-egypt/

Figure 2 shows that for all immigrants the enterprise formation rate — the number of new business start-ups — increases over time. However, for migrants who arrived under a family visa and skilled visa the rise is slight while for refugees the rate of business formation increases dramatically after seven years of settlement in Australia. While the barriers to refugee entrepreneurship are substantial for refugees, their financial capital, social capital, and linguistic capital can be built over time. Similarly, the size of the local refugee community builds over time, which is important not only from an economic viewpoint but also a social and cultural one. Family and community links sustain refugee life and assist in settlement outcomes for refugee communities in countries such as Australia.

Figure 2: Refugee enterprise formation by years in Australia

Source: Nikhil Sonnad, “Refugees the Most Enterprising in Australia”, Quartz, 8 September 2015, https://qz.com/1152397/photos-of-the-two-ancient-tombs-just-been-opened-in-luxor-egypt/

Research from Canada also attests to high rates of entrepreneurship among refugees: “While immigrant business ownership rates are low immediately after entry, after four to eight years in Canada they surpass those of the comparison group (largely Canadian-born) … The per capita job creation rate via unincorporated self-employment was higher among immigrants than the Canadian-born … Immigrants in the family and refugee classes accounted for 40 per cent to 50 per cent of all immigrant business ownership”.[58] Similarly, in Germany the self-employed with a migrant background make a substantial contribution to employment: in 2014 migrant entrepreneurs employed at least 1.3 million people. This figure has grown by 36 per cent since 2005.[59]

In the United States, research on refugee or ethnic entrepreneurship confirms that small business ownership is a pathway towards self-sufficiency and success for refugees and immigrants.[60]

Hazara refugee entrepreneurs in Adelaide

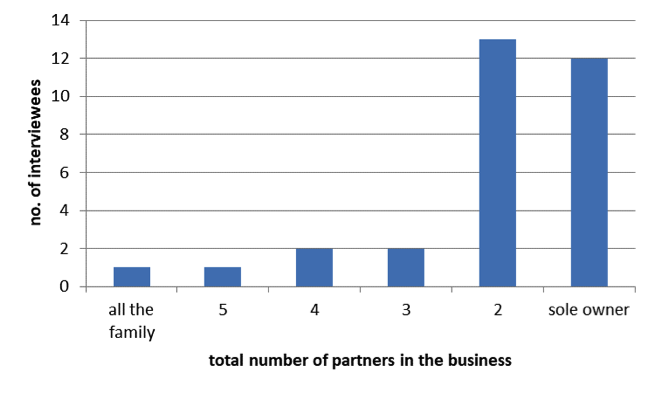

A newly completed report into 32 Hazara refugee entrepreneurs in Adelaide provides some insight into the refugee entrepreneurship paradox in Australia.[61] Of the 32 Hazara refugee entrepreneur respondents, 15 arrived as ‘boat people’ and spent time in detention — most in the Woomera Detention Centre in South Australia — before moving to Adelaide to settle. The other respondents were sponsored by relatives and arrived under the family reunion program. The Hazara refugee entrepreneurs overcame their lack of start-up capital by saving from meagre wages over many years, working in factories and unskilled manual jobs. The businesses that they established were clustered into business type and location. While a majority of the Hazara refugees set up restaurants and supermarket/grocery stores, others established a diverse range of businesses, including tourism and translation services, automotive spare parts, childcare, painting, furniture stores, driving schools, taxis, and tyre services. Most were run by males. A total of 12 businesses were sole-ownerships, the rest were partnerships, often with other Hazara that the owners had met in detention camps, building their social capital and, in many instances, lifelong friendships. Like many refugees, one in three of the Hazara refugee entrepreneurs in Adelaide had experience with entrepreneurship prior to arriving in Australia. This tradition of prior entrepreneurship — often informal businesses and some even in refugee camps — is one reason why supporting refugee entrepreneurship is fertile in countries such as Australia.

Figure 3: Hazara refugee business partnerships

Source: Jock Collins, Branka Krivokapic-Skoko and Katherine Watson, From Boats to Businesses: The Remarkable Journey of Hazara Refugee Entrepreneurs in Adelaide, Centre for Business and Social Innovation (Sydney: UTS Business School, 2017), https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/2017-10/From%20Boats%20to%20Businesses%20Full%20Report%20-%20Web.pdf

The Hazara refugee entrepreneurs generated substantial employment for others, including 130 full-time employees: 10 businesses employed one person, 7 employed two people, and 4 employed three people. Eleven businesses employed more than three people, with one business employing 80 people and another employing 870 subcontractors.

Table 1: Number of Hazara businesses employing staff

No of employees | No of businesses employing each category | |||||

Full time | Casual | |||||

Refugees | Family members | Others | Refugees | Family members | Others | |

1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

|

2 | 4 | 2 |

|

|

| 1 |

3 | 2 |

| 1 | 1 |

|

|

4 |

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

6 |

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

8 |

|

| 1 |

|

| 1 |

9 |

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

20+ |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

80+ |

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

870 subcontractors |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

For the majority of Hazara refugee entrepreneurs, the Australian business they established was their first. They were necessity entrepreneurs, moving into business because their mobility in the Australian labour market was blocked by formal and informal institutional racial discrimination.[62] And yet these same Hazara refugee entrepreneurs did not subscribe to narratives that Australia was a racist society. Few had personal experiences of racism in Adelaide, and those who did merely commented that it was no worse than they experienced in Afghanistan and other countries. Most adult Hazara boat people arrived in Adelaide with little formal education, after having been denied access to human capital by the Taliban in Afghanistan. They went to English language classes to improve their linguistic capital, which is needed to thrive as an entrepreneur in the Adelaide economy. The older Hazara found that their low-wage employment was not satisfying nor sufficiently lucrative. Many younger Hazara had Australian schooling and acquired Australian human capital — often at tertiary level — so did not have the human capital barriers to entrepreneurship that their parents or older siblings faced. But another potentially insurmountable hurdle emerged: they could not get jobs in Adelaide in their professions.

Today the Hazara community in Adelaide is thriving, optimistic, engaged and thankful for and committed to life in Australia. They built strong Hazara community networks in Adelaide to overcome the lack of social capital that refugee entrepreneurs face in Australia. The strong picture that emerges from this research is of Hazara refugee entrepreneurs who are very hard-working individuals determined to provide their families with a better life in Australia than the one that they had experienced in Afghanistan and during their long dangerous journey to Australia. They had plans for the business future: some wanted to expand and grow their current business, take on more employees — particularly other Hazara refugees — move to bigger premises, or better business locations. Others were keen to try a new business, relentlessly looking out for business opportunities. All Hazara refugee entrepreneurs were strongly embedded in their family and their community. Not only did they make a positive contribution to the Adelaide neighbourhoods where they lived and worked, they also enlivened the Adelaide economy, keen to promote employment and trade growth, to innovate and change wherever possible.

Policy reponses to assist new refugee business start-ups

Australia

While there is very little policy development designed specifically to support immigrant entrepreneurship in Australia, there is a long and strong tradition of developing and refining immigration policy to attract immigrant entrepreneurs.[63] Since the Business Migration Program was established in the late 1970s, immigration policy has been refined to attract immigrants who were already in business overseas.[64] In the most recent iteration of the program, reforms to the Significant Investor Visa stream of the Business Innovation and Investment Programme (BIIP) were introduced in July 2015. They included a new Complying Investment Framework (CIF) and a new Premium Investor Visa (PIV) stream. The CIF encouraged investment in emerging enterprises and the promotion of local commercialisation of innovative research and development. The PIV was designed to boost the Australian economy by attracting high investments and allows applications for permanent residence after 12 months. In September 2016, a new Entrepreneur visa was introduced for those with innovative ideas and A$200 000 in financial backing from a specified third party wishing to develop or commercialise innovative ideas in Australia. The Entrepreneur visa provides a pathway to permanent residency.

The big policy gap is in assisting immigrants who arrive via other visas pathways, including humanitarian pathways, to establish and sustain a business in Australia. Recent initiatives have attempted to redress this policy gap. In 2014 Settlement Services International — a Sydney-based service provider to refugees and other migrants — established the Ignite Small Business Start-ups Program. The three-year pilot program assists newly arrived refugees to establish a business in Sydney. Two full-time enterprise facilitators were employed for the three-year period. Their task was to support their humanitarian clients establish a business, supported by a resources team of 120 professionals who volunteered their time and expertise to assist. Initially based on the Sirolli Institute’s community-based enterprise facilitation model for aspiring entrepreneurs,[65] the Ignite model developed into a social ecology model of refugee enterprise start-ups.[66] This was because the enterprise facilitators found that a more hands-on approach was required than that allowed for in the Sirolli model. Ignite clients had a history of displacement and many had experienced torture and trauma before arriving in Australia, meaning that most had arrived in incomplete family units or alone. To help steer them on their journey to entrepreneurship the enterprise facilitators found they needed to intervene in almost all aspects of the refugees’ lives and be with them through all stages of the process. They acted as counsellors, friends, and sounding boards. They arranged microfinance loans for their clients, found marketplaces for them, engaged students as mentors, organised web pages and logo design through the resources team, arranged for accountancy and marketing advice, found raw materials and supplies, and introduced their clients to potential markets and customers.

The outcomes of the Ignite initiative are remarkable: humanitarian entrants have created 66 new businesses across a wide range of industries in less than three years since arriving in Sydney in 2014. Another 174 clients are in the pipeline and could establish businesses with appropriate resourcing. Table 2 shows the diversity of national backgrounds of 54 of the Ignite refugee entrepreneurs — 13 of whom are female — and the diversity of business types they have established in Sydney. The majority of these successful Ignite clients were from countries in the Middle East: 29 from Iran, eight from Syria, four from Iraq, two from Afghanistan, and one each from Lebanon, Egypt and Palestine. Other refugee entrepreneurs were from Kenya, Sierra Leone, Tibet, Fiji, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, and China.

Table 2: Businesses owned and operated by Ignite entrepreneurs

Gender and Client No | Ethnicity | Business type |

|---|---|---|

M 1 | Kenya | Coffee/Barista |

M 2 | Iran | Photographer |

F 3 | Iran | Photographer |

F 4 | Lebanon | Catering |

M 5 | Iraq | Carpentry and joinery |

M 6 | Afghanistan | Import/export |

M 7 | Iran | Electrician |

F 8 | Iran | Fashion design |

M 9 | Iraq | Photographer |

M 10 | Iran | Handyman |

F 11 | Iran | Hairdressing |

M 12 | Iran (Kurdish) | Innovator |

M 13 | Syria | Construction |

M 14 | Iraq | Artist |

M 15 | Iraq | Artist |

M 16 | Iran | Artist |

M 17 | Iran | Artist |

M 18 | Syria | Film Director |

F 19 | Sierra Leone | Videographer |

M 20 | Sierra Leone | Fashion design |

F 21 | Tibet | Jewellery design |

F 22 | Fiji | Hairdressing |

M 23 | Syria | Pranic healing |

F 24 | Iran | Leather goods |

F 25 | Afghanistan | Driving instructor |

F 26 | Iran | Photographer |

F 27 | Iran | Cleaning |

M 28 | Iran | Café/Restaurant |

M 29 | Iran | Café/Restaurant |

M 30 | Singapore | Catering |

M 31 | Syria | Internship consulting/employment |

M 32 | Iran | Fencing |

M 33 | Iran | Floor sanding |

M 34 | Iran | Scaffolding |

M 35 | Sri Lanka | Café/Restaurant |

M 36 | Pakistan | Taxi driver |

M 37 | Nepal | Hat retail |

M 38 | Iraq | Photographer |

F 39 | Iran | Photographer |

M 40 | Iran | Removalist |

M 41 | Iran | Signage |

M 42 | Egypt | Artist |

M 43 | Iran | Painter (commercial) |

M 44 | China | Cleaning |

M 45 | Palestine | Carpentry and joinery |

M 46 | Iran | Import |

F 47 | Iran | Hairdressing |

M 48 | Iran | Electrician |

M 49 | Iran | Butcher |

M 50 | Iran | Hairdressing |

M 51 | Syria | Baker |

M 52 | Iraq | Photographer |

M 53 | Iran | Coffee/Barista |

M 54 | Iran | Café/Restaurant |

These new Ignite refugee entrepreneurs have created 20 jobs so far.[67] The economic benefits of the Ignite program include the savings on welfare payments, the tax revenue generated by the business enterprise in the form of company tax and GST, the tax revenue generated by the employees of the refugee enterprises, and the benefits of the innovation that new refugee entrepreneurs bring to the Australian economy. The social and psychological benefits include the new friends the Ignite clients made in Sydney from participating in the program. This builds their social capital, which is useful both in a business and personal sense. Most clients reported that their English language fluency increased dramatically since they have been engaged in the Ignite program. This builds their linguistic capital and in turn contributes to their business success and their daily lives as part of the broader cosmopolitan Sydney community.[68]

Another recent initiative in the refugee enterprise start-ups space is the Thrive program, which is designed to address the financial barrier that newly arrived refugees face when setting up a business. Backed by Westpac — which has provided A$2 million in funding towards microfinance loans and support for refugees who want to start their own business — the program provides loans of up to A$20 000 to approved refugee clients. Some clients have accessed this finance to buy a car to join the Uber business. The program will also assist with further education programs, qualifications and apprenticeships, and business mentoring.[69] Another Australian initiative, Catalysr, which began in 2016, runs an entrepreneurial program, including one-on-one mentoring sessions with experts in start-ups and professional services, a co-working space to collaborate with other refugees and migrants, and a network of investors, philanthropists and loan providers, politicians, potential customers and suppliers. Run by a not-for-profit organisation, it works on a pay-it-forward scheme. Participants pay back their costs only once their business begins trading and they receive an income of A$50 000 per year, at which time they pay 5 per cent of the business’s revenue (up to a total cap of A$50,000) to put back into the program to help fund future participants.

Other countries

At the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum at Davos in 2016 Hélène Rey of the London Business School proposed the establishment of a Refugee Integration Fund that would indirectly provide microfinancing to refugee entrepreneurs. A Special Purpose Vehicle would be created to act as a lender to Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) in Europe as well as an issuer of notes to investors. The MFIs would provide loans to refugees.[70] According to Rey, the idea and investment structure have been validated “by scholars, social finance consultants, EIF structuring and guarantee professional, and securitization professional”.[71]

There have been many policy initiatives in OECD countries to support immigrant entrepreneurship. These take two main forms: support measures for immigrant entrepreneurs already established in the receiving country; and immigration policies designed to attract immigrants who are already entrepreneurs and investors abroad whose human and financial capital and business plans are likely to meet the country’s economic needs and ensure the success of their businesses.[72]

Examples of the former include Unternehmer ohne Grenzen (Entrepreneurs without Borders) and the UK’s Ethnic Minority Business Service (EMBS). Founded in 2000, Entrepreneurs without Borders is funded by the City of Hamburg and the European Social Fund and provides services and training to immigrant entrepreneurs and facilitates their access to mainstream business organisations and local business structures. EMBS offers a targeted support program for entrepreneurs with an immigrant background, covering all aspects of business development from help with start-up finance to ongoing support for more mature businesses. Immigrant businesses assisted by the Entrepreneurs without Borders program between 2001 and 2006 showed a 90 per cent two-year business survival rate against a national benchmark of 62 per cent.[73]

In the United States the Department of Health and Human Services/Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) oversees refugee resettlement programs that emphasise employment and self-sufficiency. While most resettlement programs focus on refugee employment, there are a handful of state programs that focus on refugee self-sufficiency through entrepreneurship or self-employment. The ORR maintains three programs for microenterprise development — the Microenterprise Development Program (MED), the Individual Development Accounts Program (IDA), and the Refugee Agricultural Partnership Program (RAPP).

The MED provides discretionary grants to public or private non-government organisations (NGOs) that offer business training, technical assistance, and microloans (up to US$15 000) to refugees looking to start their own businesses. In fiscal year 2015, ORR awarded 22 grants across 20 states, totalling US$4.5 million and providing services to over 2000 refugees. Businesses that were created or retained through the MED program that year contributed 1163 jobs to the US economy.[74] The Refugee Family Child Care Microenterprise Program is another service that helps refugees establish small home-based childcare businesses so they can earn a reliable income while caring for their own children as well as children from other refugee families. Under this program, ORR awarded 23 grants totalling $4.6 million in fiscal year 2015, and grantees provided training to more than 500 individuals, assisting more than 200 refugees in opening childcare businesses and creating more than 1000 childcare slots.[75]

The success of refugee microenterprise programs relies on factors such as the program’s mission, market, staff, training, technical support, partnership, business, financing, administrative capacities and practices, the target population, the type of businesses developed, adaptability and flexibility, and start-up time.[76] Over the period 1991–2002, ORR awarded almost US$20 million to agencies and over 21 per cent of participants in the program started, expanded or strengthened their businesses. These businesses had an 89 per cent business survival rate and contributed to the creation of 2600 full-time jobs.[77]

The MED is largely considered a success. Since 1991, it has distributed US$10.03 million in loans to approximately 24 000 refugees, with a loan repayment rate of 98 per cent, a rate far higher than the average repayment rate in the industry.[78] And 90 per cent of business that participated in MED programs have survived, a much better outcome than national average survival rates and substantially higher than other microenterprise programs in the United States.[79]

Both MED and IDA programs are notable for their success in helping newly arrived refugees open and manage their own businesses and in fiscal year 2010 alone helped nearly 1000 such businesses.[80] MED and IDA programs also have much lower default and higher completion rates than mainstream counterpart programs. With the help of these programs, within the first few years after resettlement refugees have used their savings to leverage millions of dollars in additional resources, expanding businesses and opening the door to higher levels of success and self-sufficiency.[81]

A significant advantage of both MED and IDA programs is that services are administered to refugees by partnering with organisations that have a more intimate understanding of local refugee populations.[82] Problems of adjustment to the mainstream culture, English language competency, mastering the new work environment, and obtaining networking skills to establish successful businesses have been identified as prevailing challenges to refugees in the United States.[83] By utilising intermediary organisations, refugees can obtain funding and training through organisations that understand these challenges and are nimble enough to customise their programs according to the ever-changing refugee constituencies.

Sometimes, this results in very innovative solutions. For example, one MED grantee, the International Rescue Committee’s enterprise program in San Diego, offers interest-free loans specifically for Muslim clients, the only institution to do so country wide.[84] Other strengths of the MED include its emphasis on short-term, one-on-one training, and the many benefits that it brings to refugees’ self-esteem, incomes, and job creation.[85]

Finally, the RAPP creates opportunities for refugees to improve their self-sufficiency through agricultural and rural entrepreneurship using collaborative partnerships.[86] Unlike the MED, those who participate in the RAPP tend to be refugees who come from agrarian societies, have the skills and aptitudes for farming, but have limited education and language skills. Most refugees involved in this grant have off-farm income, and RAPP income is supplementary.[87]

Private and community sector partnerships for refugee employment in Australia and other countries

There appears to be very little scholarly literature on private sector funding or mentoring of refugee businesses or employment. Despite this, the private sector — particularly corporations but also the SME sector — can play an increasingly important role in generating employment for newly arrived refugees, especially in partnership with community sector organisations. In its Immigration Outlook Report 2017, the OECD notes that employers play a critical role in the integration of newly arrived Syrian-conflict refugees: “Employers and social partners are important stakeholders in the integration of refugees. Not surprisingly, therefore, in a growing number of OECD countries they are actively involved in integration, especially in countries where social partnership is strong.”[88]

The OECD report notes that in Austria, the public employment service, NGOs, sector councils, and employers gather labour market information and promote good matching via career guidance and effective work placements under the competence check program for the occupational integration of refugees. In Germany, local chambers of commerce provide advice and training to SMEs on issues related to the implementation of work-based learning programs, employment, and internships involving refugees. The initiative is supported by a network of enterprises experienced in training and hiring refugees that share their experiences and provide advice to peers. In Sweden larger private sector employers that take in at least 100 refugees receive tailored support and package solutions from the public employment service under the ‘100 Club’ initiative. In Denmark companies that recruit refugees or individuals who arrived to reunite with family within one year of residency receive a bonus worth €5300, while those who recruit refugees in their second year of residence receive €4000. In March 2016, Denmark concluded tripartite agreements with social partners and 98 municipalities on more than 80 labour market integration measures under its ‘United for better Integration’ initiative.

Public and private sector initiatives — sometimes in partnership — in relation to refugee and immigrant settlement have a history that pre-dates the Syrian refugee crisis. Some of these relate to entrepreneurial activities, others to employment generation. One European example is venture philanthropy (VP), where capital provided by venture philanthropists is focused towards “building organisational capacity in entrepreneurial social purpose organisations, [and] matching appropriate finance with strategic business-like advice”.[89]

Other programs relate to mentoring. In Austria the ‘Mentoring for Migrants’ program, begun by the Federal Chamber of Commerce in collaboration with the Austrian Integration Fund and the Public Employment Service, matches highly qualified immigrants with well-connected members of the business community. In Germany the ‘Joblinge’ project, developed by Boston Consulting Group and the Eberhard von Kuenheim Foundation of the BMW Group of companies, provides internships and mentoring to young immigrant men; Siemens has donated one million euros to support a long-term program for integrating refugees in Germany, including an internship program, German language classes and shelter facilities for refugees; and Deutsche Telekom employees have launched a training program to help refugees learn how to apply for jobs and serve as German language mentors for adults.[90] In the Netherlands the Dutch Dream Foundation, founded by the CEO of Triodor Software, supports starting entrepreneurs of an ethnic minority background to thrive and succeed in their businesses. The Swedish Engineers association has developed a mentoring program for newly arrived engineers, and the Swedish Medical Association is helping immigrant doctors enter the Swedish healthcare system.[91] Telefonica in Spain has a program where employee volunteers serve as one-on-one mentors for refugees, assisting with a variety of assimilation tasks including understanding the local transportation network and guidance on work-related issues.[92]

In Canada the Hire Immigrants Ottawa initiative is a collaboration between community partners, stakeholders and Council members with “numerous local employers acting to reframe employment practices, implement systemic workplace change, and most importantly, to realize the benefits of diverse and inclusive workplaces”.[93] The initiative enhances an employer’s ability to access the talents of skilled immigrants in general, rather than refugees specifically, by offering “information products, professional development training, learning events, networking opportunities, and one-on-one consultations”.[94] Annual Employer Excellence Awards are presented for outstanding practices in the recruitment and retention of skilled immigrants in their workplaces. More recently, private sponsors, volunteers, and ethnic communities have offered assistance for private sector employment of Syrian refugees in Canada and employers have reached out to settlement agencies.[95] Moreover, the Royal Bank of Canada has developed employee volunteer activities and provided C$1 million in funding to the Immigrant Access Fund Canada, which provides microloans of up to C$10 000 to internationally trained immigrants, including refugees, so they can obtain the Canadian licensing or training they need to work in their field.[96]

Corporations around the globe have pooled resources in campaigns designed to assist refugees. For example, the global TENT Foundation has partner businesses in several regions across Asia, Europe, America, and Africa, and in industries including consumer goods, education, financial services, health care, logistics, mass media, professional services, technology, travel and hospitality.[97] To belong to the Tent Partnership for Refugees, businesses must commit to supporting refugee-related efforts through activities. These can include generating employment opportunities by either hiring refugees or by providing refugees with skills training or employment assistance. The program works with companies such as LinkedIn Sweden, which leverages its network to help refugees find jobs and to present themselves in the best possible way in their LinkedIn profiles.[98] The TENT Foundation was launched by former refugee Hamdi Ulukaya, founder and CEO of Chobani where 30 per cent of employees have been migrants or refugees. Similarly, the ‘We together’ initiative was launched by another CEO, Wir Zusammen — the billionaire founder and chief executive of United Internet, Germany’s largest internet service provider. This initiative began with 36 companies, including Deutsche Post, Deutsche Telekom, and Deutsche Bank, but has grown to 150 companies, including more than half of the 30-member Dax, Germany’s leading stock market index, as well as international companies such as Google, McDonald’s, and Procter & Gamble.[99] By December 2016, 2800 migrants had been placed into internships, 630 into trainee positions and 557 into full-time jobs, while about 16 900 mentors help with language training and writing CVs. The steelmaker, ThyssenKrupp, has created 150 apprenticeships and 230 internships solely for refugees.[100]

Conclusion and recommendations

In the past few years refugee settlement in Western countries has increased significantly in countries such as Australia and Canada, and increased dramatically in countries such as Germany, Sweden, Greece, and Italy. While refuges displaced by the Syrian conflict were a major driver of increased refugee movement, the displacement of peoples from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and other parts of the globe continues. This working paper has focused on the importance of refugee employment as a key part of any strategy for refugee settlement in receiving countries. However, the increasing numbers of refugee arrivals puts pressure on policies and programs designed to assist refugee resettlement and integration. This means that innovative solutions to employment creation for refugees are even more critical.

Refugee entrepreneurship and the role of the private sector, often in collaboration with the community sector, in employment creation for refugees is particularly important. While the track record in Australia and internationally has been patchy in these areas to date, both hold the potential of making significant inroads into refugee employment creation if more adequately prioritised by corporations and SMEs in the private sector, social enterprises, NGOs, and governments at the local, provincial and national level.

The federal and state governments have responded to the need to provide refugees with employment and some innovative developments have been recently introduced. On 1 July 2017, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection introduced the Community Support Programme (CSP) that enables communities and businesses, as well as families and individuals, to propose humanitarian visa applicants with employment prospects for support in their settlement journey. Under the CSP, Australian supporters (through their Approved Proposing Organisation) are required to demonstrate they are able to provide adequate support to enable new arrivals to achieve financial self-sufficiency within the first year in Australia and to engage with employers to source employment opportunities for CSP entrants. The 2017–18 Humanitarian Programme includes up to 1000 places under the CSP.[101] In October 2017 the federal Department of Employment held the first Refugee Employment Information Expo in Sydney. The Expo, which was designed to help overcome the barriers to securing that all-important first job in a new country, attracted about 500 newly arrived refugee jobseekers and 25 potential employers.[102]

At the state level the NSW government has introduced the Refugee Employment Support Program (RESP), a four-year $22 million initiative designed to address the challenges that are experienced by refugees and asylum seekers in finding long-term skilled employment opportunities. The RESP aims to assist up to 6000 refugees and 1000 asylum seekers across Western Sydney and the Illawarra, the areas where a majority of refugees in New South Wales settle. The program is being delivered by Settlement Services International (SSI), and is an example of an innovative government and community-based not-for-profit sector collaboration designed to assist refugees overcome the barriers to their participation in the labour market.

In its response to the challenges created by the Syrian refugee intake, the NSW government has encouraged both corporate and community sector involvement in the tasks of refugee employment creation. Allianz introduced a Sustainable Employment Program in 2016 to provide permanent employment opportunities to refugees and asylum seekers in cooperation with the NSW government and SSI. The AMP Foundation has committed to working with the NSW government and the community to help improve employment, training, and educational outcomes for refugees. Australia Post supports the Refugee Settlement Program by providing refugees with an Australian workplace experience. ClubsNSW introduced a new pilot program by providing up to 30 long-term employment opportunities for settled and job-ready refugees at registered clubs in the Greater Western Sydney region. The NRMA piloted two refugee driver education programs — one in Western Sydney and another in the Illawarra. Other corporations supporting the NSW and commonwealth governments to build employment opportunities for humanitarian refugees from Syria and Iraq include Harvey Norman, Woolworths, Transurban, Telstra, Henry Davis York, First State Super, Crescent Wealth, and Clayton Utz.

At the same time, programs such as SSI’s Ignite and Thrive indicate the largely untapped potential of refuges to create their own employment through establishing their own business in Australia. Australia appears to lead the world in relation to assisting refugee business start-ups, with the Canadian Government committed to an application of the Ignite initiative in five Canadian cities and the German Government also considering a program of refugee business start-ups modelled on Ignite. The national and international potential of policies supporting refugee entrepreneurship to assist refugees to overcome the barriers to their engagement with the economy and the introduction of new private, public, and community sector partnerships for refugee employment creation are a promising response to the new challenges of refugee settlement in Australia and other societies.

Recommendations

- Entrepreneurship is one successful pathway for refugees to overcome barriers that block their access to the economy and allows refugees to create their own job. The public, corporate, and community sector should put greater resources into developing new policies and programs to support refugee entrepreneurship in Australia.

- The three-year Ignite small business start-ups program has successfully piloted a model of assisting newly arrived refugees to establish a business in Sydney. The federal and state government authorities should allocate funds to extend the Ignite model in Sydney for a further three years and to roll out three-year pilots of this program in all other Australian states and territories.

- The public, corporate, and community sector should cooperate on establishing programs to support entrepreneurship among the new Syrian-conflict cohort.

- The public, corporate, and community sector should cooperate on establishing a national Australian Refugee Employment Compact to assist refugees in finding employment.

Acknowledgements

This working paper series is part of the Lowy Institute’s Migration and Border Policy Project, which aims to produce independent research and analysis on the challenges and opportunities raised by the movement of people and goods across Australia’s borders. The Project is supported by the Australian Government’s Department of Immigration and Border Protection. The views expressed in this working paper are entirely the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy or the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

About the Author

Jock Collins is Professor of Social Economics in the Management Discipline Group at the UTS Business School, Sydney. He has been teaching and conducting research at UTS since 1977. He is a member of the Centre for Business and Social Innovation at UTS. His research interests centre on an interdisciplinary study of immigration and cultural diversity in the economy and society and on minority entrepreneurship. He has had visiting academic appointments in the United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden, and the United States and has consulted to the ILO and OECD.

Notes

[1] UNHCR, “Statistical Yearbooks: Figures at a Glance”, 19 June 2017, http://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html.

[2] UNHCR, “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2015”, 20 June 2016, 7, http://www.unhcr.org/576408cd7.pdf.

[3] OECD, International Migration Outlook 2015 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015), 49.

[4] Refugee Council of Australia, “Australia’s Response to a World in Crisis: Community Views on Planning for the 2016–17 Humanitarian Program”, March 2016, 25. http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/2016-17-Intake-submission-FINAL.pdf.

[5] Elibritt Karlsen, “Refugee Resettlement to Australia: What Are the Facts?”, Parliamentary Library Research Paper Series, 2016–17, updated 7 September 2016, 10, http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/4805035/upload_binary/4805035.pdf;fileType=application/pdf.

[6] D Groutsis, J Collins and C Reid, “Enacting Solidarity: An Inclusive and Sustainable Solution for the Refugee Crisis”, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Conference, University of Cyprus, 22–24 June 2016.

[7] Janet Phillips and Joanne Simon-Davies, “Migration to Australia: A Quick Guide to the Statistics”, Parliamentary Library Research Paper Series, 2016–17, updated 18 January 2017, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1617/Quick_Guides/MigrationStatistics.

[8] Farida Fozdar, “Aussie Cows and Asylum Seekers: Cartooning About Two Key Political Issues”, in Renate Brosch and Kylie Crane eds, Visualising Australia: Images, Icons, Imaginations (Germany: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2014).

[9] OECD, Immigration Outlook 2017 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2017), 1.

[10] Steven Koltai, “Refugees Need Jobs. Entrepreneurship Can Help”, Harvard Business Review, 29 December 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/12/refugees-need-jobs-entrepreneurship-can-help.

[11] OECD, Immigration Outlook 2017, 2.

[12] Khalid Koser, A Global Compact on Refugees: The Role of Australia, Lowy Institute Analysis (Sydney: Lowy Institute, 2017), https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/global-compact-refugees-role-australia.

[13] OECD, “Entrepreneurship and Migrants”, Report by the OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship (OECD Publishing, 2010).

[14] OECD, Immigration Outlook SOPEMI 2011 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2011), 158.

[15] Centre for Entrepreneurs, “Migrant Entrepreneurs: Building our Businesses, Creating our Jobs”, A Report by Centre for Entrepreneurs and DueDil, March 2014, 3, 35, https://centreforentrepreneurs.org/cfe-research/creating-our-jobs/.

[16] Ibid, 30.

[17] Trevor Jones, Monder Ram, Yaojun Li, Paul Edwards and Maria Villares, “Super-diverse Britain and New Migrant Enterprises’, IRiS Working Paper Series, No 8/2015, Birmingham: Institute for Research into Superdiversity (2015), 15.

[18] Jock Collins, Stephen Castles, Katherine Gibson, David Tait and Caroline Alcorso, A Shop Full of Dreams: Ethnic Small Business in Australia (Sydney; London: Pluto Press, 1995); Jock Collins, “Australia: Cosmopolitan Capitalists Down Under”, in Robert Kloosterman and Jan Rath eds, Immigrant Entrepreneurs: Venturing Abroad in the Age of Globalisation (New York; Oxford: New York University Press and Berg Publishing, 2003), 61–78; Jock Collins and Angeline Low, “Asian Female Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Small and Medium-sized Businesses in Australia”, Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22, Issue 1 (2010), 97–111; Jock Collins and Joon Shik Shin, “Korean Immigrant Entrepreneurs in the Sydney Restaurant Industry”, Labour and Management in Development 15 (2014), 1–25.

[19] Maria Vincenza Desideiro, Policies to Support Immigrant Entrepreneurship (Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2014).

[20] ‘Bottom-up innovation’ is “the way in which crisis-affected communities engage in creative problem solving, adapting products and processes to address challenges and create opportunities”: Alexander Betts, Louise Bloom and Nina Weaver, “Refugee Innovation: Humanitarian Innovation that Starts with Communities”, Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford, July 2015, 3, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/refugee-innovation-web-5-3mb.pdf.

[21] ‘Humanitarian innovation’ relates to the abilities of refugees, displaced persons, and others caught in crisis to draw on their skills, talents, and aspirations in order to adapt to difficult circumstances.

[22] Betts et al, “Refugee Innovation: Humanitarian Innovation that Starts with Communities”, 42.

[23] Fergus Lyon, Leandro Sepulveda and Stephen Syrett, “Enterprising Humanitarian Immigrants: Contributions and Challenges in Deprived Urban Areas”, Local Economy 22, No 4 (2007), 362–375.

[24] Bram Wauters and Johan Lambrech, “Refugee Entrepreneurship in Belgium: Potential and Practice”, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 2, Issue 4 (2006), 509–525.

[25] Cailynn Klingbeil, “Despite Struggles, Many Syrian Refugees Businesses Are Gaining Traction”, The Globe and Mail, 25 April 2017, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/small-business/sb-managing/many-syrian-refugees-launched-businesses-when-they-came-to-canada-how-are-they-faring-now/article34799676/.

[26] Doug Saunders, Arrival City: How the Largest Migration in History is Reshaping our World (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2010).

[27] Kathleen Newland and Hiroyuki Tanaka, Mobilizing Diaspora Entrepreneurship for Development (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2010), 23.

[28] Lyon et al, “Enterprising Humanitarian Immigrants: Contributions and Challenges in Deprived Urban Areas”.

[29] Mark Grey, Nora Rodríguez and Andrew Conrad, Immigrant and Refugee Small Business Development in Iowa: A Research Report with Recommendations, New Iowans Program University of Northern Iowa, 2004.

[30] Miriam Potocky-Tripodi, “The Role of Social Capital in Immigrant and Refugee Economic Adaptation”, Journal of Social Service Research 31, No 1 (2004), 59–91; Rowena Fong, Noel Bridget Busch, Marilyn Armour, Laurie Cook Heffron and Amy Chanmugam, “Pathways to Self-sufficiency: Successful Entrepreneurship for Refugees”, Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 16, Nos 1–2 (2007), 127–159.

[31] John Else, Daniel Krotz and Lisa Budzilowicz, Refugee Microenterprise Development: Achievements and Lessons Learned, 2nd Edition (Washington DC: ISED Solutions, 2003).

[32] Grey et al, Immigrant and Refugee Small Business Development in Iowa: A Research Report with Recommendations.

[33] Vaishali Mamgain and Karen Collins, “Off the Boat, Now Off to Work: Refugees in the Labour Market in Portland, Maine”, Journal of Refugee Studies 16, No 2 (2003), 113–146.

[34] Graeme Hugo, Economic, Social and Civic Contributions of First and Second Generation Humanitarian Entrants (Canberra: Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 2011), https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/economic-social-civic-contributions-about-the-research2011.pdf.

[35] Farida Fozdar and Lisa Hartley, “Refugee Resettlement in Australia: What We Know and Need to Know”, Refugee Survey Quarterly 32, No 3 (2013), 23–51.

[36] Jock Collins, “The Global Financial Crisis, Immigration and Immigrant Unemployment, and Social Inclusion in Australia”, in John Higley, John Nieuwenhuysen and Stine Neerup eds, Immigration and the Financial Crisis: The United States and Australia Compared, Monash Studies in Global Movements Series (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011), 145–158.

[37] Hugo, Economic, Social and Civic Contributions of First and Second Generation Humanitarian Entrants, 109.

[38] Val Colic-Peisker and Farida Tilbury, “Refugees and Employment: The Effect of Visible Difference on Discrimination: Final Report”, Centre for Social and Community Research, Murdoch University, January 2007, http://library.bsl.org.au/jspui/bitstream/1/811/1/Refugees%20and%20employment.pdf; Val Colic-Peisker, “Visibility, Settlement Success and Life Satisfaction in Three Refugee Communities in Australia”, Ethnicities 9, No 2 (2009), 175–199.

[39] Centre for Policy Development, “Settling Better: Reforming Refugee Employment and Settlement Services”, February 2017, 9, https://publicimpact.blob.core.windows.net/production/2017/02/Settling-Better.pdf.

[40] Ibid, 15.

[41] Ibid, 5.

[42] Ibid, 14.

[43] Ibid, 15.

[44] Ibid, 21.

[45] Ruth Ostrow, The New Boy Network (Richmond: William Heinemann Australia, 1987); Michael Bleby, Caitlin Fitzsimmons and Nassim Khadem, “We Came by Boat: How Refugees Changed Australian Business”, Business Review Weekly, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 September 2013, http://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/we-came-by-boat--how-refugees-changed-australian-business-20130905-2t73t.html.

[46] Ivan Light, Ethnic Enterprise in America (Berkley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1972).

[47] Jock Collins, Chenglian Sim and Basundhara Dhungel, Training for Ethnic Small Business: Responding to the NESB Segment of the Small Business Training Market — Main Report (Sydney: NSW TAFE Multicultural Education Unit and the Faculty of Business, UTS, 1997), 154.

[48] Christine Stevens, “Balancing Obligations and Self-interest: Humanitarian Program Settlers in the Australian Labor Market”, Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 6, Issue 2 (1997), 185–212.

[49] Hugo, Economic, Social and Civic Contributions of First and Second Generation Humanitarian Entrants, xxiv.

[50] Collins, “Australia: Cosmopolitan Capitalists Down Under”.

[51] Hugo, Economic, Social and Civic Contributions of First and Second Generation Humanitarian Entrants, 176.

[52] Collins and Low, “Asian Female Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Small and Medium-sized Businesses in Australia”.

[53] Collins et al, A Shop Full of Dreams: Ethnic Small Business in Australia; Collins, “Australia: Cosmopolitan Capitalists Down Under”: Collins and Low, Ibid; Collins and Shin, “Korean Immigrant Entrepreneurs in the Sydney Restaurant Industry”.

[54] Australian Industry Group, “Casual Employment in Australia: Numbers and Trends”, Economics Fact Sheet, March 2016, https://cdn.aigroup.com.au/Economic_Indicators/Fact_Sheets/2016/casual_employment_factsheet_Mar_2016_version_3.pdf.

[55] Collins and Low, “Asian Female Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Small and Medium-sized Businesses in Australia”.

[56] ABS, “Personal Income of Migrants, Australia, Experimental, 2009–10”, ABS Cat No 3418.0, 4 September 2015, http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Previousproducts/3418.0Media%20Release12009-10?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3418.0&issue=2009-10&num=&view=.

[57] Ibid.

[58] David Green, Huju Liu, Yuri Ostrovsky and Garnett Picot, “Immigration, Business Ownership and Employment in Canada”, Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series (Canada: Statistics Canada, Minister of Industry, 2016), 5.

[59] Andrea Sachs, Markus Hoch, Claudia Münch and Hanna Steidle (2016). Migrant Entrepreneurs in Germany from 2005 to 2014: Their Extent, Economic Impact and Influence in Germany’s Länder, BertelsmannStiftung, October 2016, 26, https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/NW_Migrant_Entrepreneurs_2016.pdf.

[60] Steven Gold, “The Employment Potential of Refugee Entrepreneurship: Soviet Jews and Vietnamese in California”, Review of Policy Research 11, No 2 (1992), 176–186; Fong et al, “Pathways to Self-sufficiency: Successful Entrepreneurship for Refugees”; Pyong Gap Min and Mehdi Bozorgmehr, “Immigrant Entrepreneurship and Business Patterns: A Comparison of Koreans and Iranians in Los Angeles”, International Migration Review (2000), 707–738; Ola Marie Smith, Rodger Tang, and Paul San Miguel, “Arab-American Entrepreneurship in Detroit, Michigan”, American Journal of Business 27, No 1 (2012), 58–79.

[61] See Jock Collins, Branka Krivokapic-Skoko and Katherine Watson, From Boats to Businesses: The Remarkable Journey of Hazara Refugee Entrepreneurs in Adelaide, Centre for Business and Social Innovation (Sydney: UTS Business School, 2017), https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/2017-10/From%20Boats%20to%20Businesses%20Full%20Report%20-%20Web.pdf.

[62] Joern Block, Karsten Kohn, Danny Miller and Katrin Ullrich, “Necessity Entrepreneurship and Competitive Strategy”, Small Business Economics 44, Issue 1 (2015), 37–54; Jeremy Brewer and Stephen Gibson eds, Necessity Entrepreneurs: Microenterprise Education and Economic Development (Cheltenham UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2014).

[63] Jock Collins, “Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Australia: Regulations and Responses”, Migrações: Journal of the Portugal Immigration Observatory, No 3 (2008), 49–59.

[64] Jock Collins, Migrant Hands in a Distant Land: Australia’s Post-war Immigration, 2nd Edition (Sydney; London: Pluto Press, 1991), 251–254.

[65] Ernesto Sirolli, Ripples from the Zambezi: Passion, Entrepreneurship and the Rebirth of Local Economies (Gabriola Island, British Columbia: New Society Publishers, 2011).

[66] In this social ecology model of assisting refugees to become entrepreneurs, the journey to entrepreneurship is embedded in the individual/economic/cultural/social context of their lives within the broader global/national/local geopolitical context. In turn, the impact of becoming a refugee entrepreneur not only on themselves but their families, their community and the broader Australian community and economy context is structured within the social ecology of their lives.

[67] In preparing the evaluation of Ignite the author interviewed and analysed the qualitative insights of 54 entrepreneurs. However, at the time of publication the number of Ignite entrepreneurs had increased to 66 as the data analysis shows. Today the number of Ignite entrepreneurs has reached 100. This is an example of the difficulties of evaluating a program that keeps developing outcomes after the evaluation date.

[68] Jock Collins, From Refugee to Entrepreneur in Sydney in Less Than Three Years (Sydney: UTS Business School, 2016), 98, http://www.ssi.org.au/services/ignite.

[69] Westpac Foundation, Westpac Foundation Annual Report 2015/16: Building a Nation Where No-one is Left Behind (Sydney: Westpac Foundation, 2016).

[70] Heather Hachigian, “Investing in Global Refugee and Migrant Integration”, Stanford Social Innovation Review, 21 September 2016, https://ssir.org/articles/entry/investing_in_global_refugee_and_migrant_integration.

[71] Hélène Rey, “Refugee Integration Fund (RIF)”, World Economic Forum, Davos, 2017, http://sustainableinvestingchallenge.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/RIF_vF.pdf.

[72] OECD, Immigration Outlook SOPEMI 2011, 160.

[73] Ibid, 162.

[74] ORR, Annual Report to Congress: Office of Refugee Resettlement Fiscal Year 2015 (Washington DC: Department of Human Health and Services, 2015), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/orr/arc_15_final_508.pdf.

[75] Ibid.

[76] John Else and Carmel Clay-Thompson, Refugee Microenterprise Development (Iowa: Institute for Social and Economic Development, 1998).

[77] Else et al, Refugee Microenterprise Development: Achievements and Lessons Learned.

[78] ORR, “About Microenterprise Development”, Office of Refugee Resettlement, 2011, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/programs/microenterprise-development/about.

[79] Else et al, Refugee Microenterprise Development: Achievements and Lessons Learned.

[80] ORR, Annual Report to Congress: Office of Refugee Resettlement Fiscal Year 2010 (Washington DC: Department of Human Health and Services, 2010), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/resource/office-of-refugee-resettlement-annual-report-to-congress-2010.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Else et al, Refugee Microenterprise Development: Achievements and Lessons Learned; ORR, Annual Report to Congress: Office of Refugee Resettlement Fiscal Year 2015.

[83] Fong et al, “Pathways to Self-sufficiency: Successful Entrepreneurship for Refugees”.

[84] Khari Johnson, “Microloans Help San Diego Refugees Grow Businesses, Jobs”, 2 February 2010, http://kharijohnson.com/microloans-help-san-diego-refugees-grow-businesses-jobs/.

[85] Peggy Halpern, Refugee Economic Self-sufficiency: An Exploratory Study of Approaches Used in Office of Refugee Resettlement Programs (Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008).

[86] ORR, “Refugee Agricultural Partnership Program”, Office of Refugee Resettlement, last reviewed 24 October 2017, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/programs/rapp/about.

[87] Halpern, Refugee Economic Self-sufficiency: An Exploratory Study of Approaches Used in Office of Refugee Resettlement Programs.

[88] OECD, Immigration Outlook 2017, 89.

[89] Rob John, Beyond the Cheque: How Venture Philanthropists Create Value (Oxford: Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, 2007), 5.

[90] Lorrie Foster, “Corporate Volunteering Response to the Refugee Challenge”, Newsletter für Engagement und Partizipation in Europa, 4/2016, http://www.b-b-e.de/fileadmin/inhalte/aktuelles/2016/05/enl-4-foster-gastbeitrag.pdf.

[91] Milica Petrovic, Mentoring Practices in Europe and North America: Strategies for Improving Immigrants’ Employment Outcomes (Brussels: Migration Policy Institute Europe, 2015), 22–24.

[92] Foster, “Corporate Volunteering Response to the Refugee Challenge”.

[93] Hire Immigrants Ottawa, “Engaging Employers. Collaborating for Change: A Three Year Review 2012–2015”, 2015, 4, http://www.hireimmigrantsottawa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/HIO-3-Year-Report-EN.pdf.

[94] Ibid, 1, 7.

[95] Borys Wrzesnewskyj, “After the Warm Welcome: Ensuring that Syrian Refugees Succeed”, Report of the Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration, Canada, House of Commons, 2016, 15.